Sihanaka

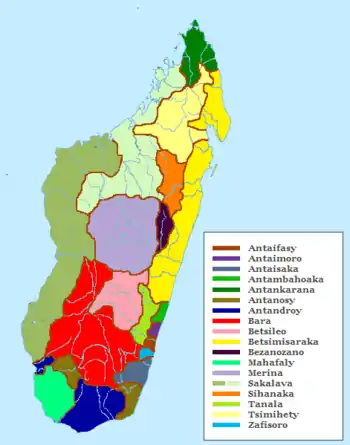

The Sihanaka are a Malagasy ethnic group concentrated around Lake Alaotra and the town of Ambatondrazaka in central northeastern Madagascar. Their name means the "people of the swamps" in reference to the marshlands around Lake Alaotra that they inhabit. While rice has long been the principal crop of the region, by the 17th century, the Sihanaka had also become wealthy traders in slaves and other goods, capitalizing on their position on the main trade route between the capital of the neighboring Kingdom of Imerina at Antananarivo and the eastern port of Toamasina. At the turn of the 19th century they came under the control of the Boina Kingdom before submitting to Imerina, which went on to rule over the majority of Madagascar. Today the Sihanaka practice intensive agriculture and rice yields are higher in this region than elsewhere, placing strain on the many unique plant and animal species that depend on the Lake Alaotra ecosystem for survival.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 200,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Malagasy groups, Austronesian peoples |

The Sihanaka have a generally egalitarian social structure, with the eldest male at the head of the family. Traditional beliefs predominate, although Christianity has also had an influence. Social life here, as elsewhere in Madagascar, is guided by the principles of respect for the ancestors and the fady (taboos) established by them. Traditional social practices include complex funeral and divorce rites and a strong and continuing prohibition on working in paddy fields on Tuesdays.

Ethnic identity

The Sihanaka are concentrated around the historically swampy land surrounding Lake Alaotra and the town of Ambatondrazaka in central northeastern Madagascar. Their name means the "people of the swamps", partly in reference to the marshlands around Lake Alaotra that they inhabit.[1] More specifically, the word for swamp is a compound composed of sia (to wander or lose one's way) and hanaka (spilling or scattering), and some ethnologists have proposed that the name evokes the earliest period in Sihanaka identity when the group's ancestors were migrating in search of the better home they eventually found at Alaotra.[2]

History

Oral history offers several stories regarding the origins of the Sihanaka. Betsimisaraka traders may have been the first to reach the area traveling inland on the Maningory River. Another view posits that the presence of ancient earthen defensive trenches suggests the ancestors of the Merina may have passed by Lake Alaotra on their migration from the southeastern coast to the central highlands, leaving behind settlers whose descendants formed the first Sihanaka communities.[3] Alternatively, a large group calling itself Sihanaka may have migrated from Imerina into the Alaotra area, which may have already been settled by individuals of various other ethnic groups, in order to maintain independence from the rule of the Merina king.[4]

At least as far back as the mid-1600s, the Sihanaka were established as a technologically sophisticated and prosperous people who provided slaves to slave traders supplying the plantations of the Mascarene Islands.[5] To protect themselves and their wealth, Sihanaka villages were often fortified by earthen walls (tamboho) of the type also prevalent in the neighboring Kingdom of Imerina. Around 1700, the Sihanaka were a major trading partner of the Betsimisaraka, to whom they traded rice and zebu. The Betsimisaraka, desirous of greater access to Sihanaka wealth, successfully negotiated for French assistance to bring the Sihanaka under their control. French militiamen launched several attacks against Sihanaka communities. This incursion was foiled through a combination of firepower - the Sihanaka having obtained numerous firearms through trade with the Sakalava to the west - and the prevalence of malaria and other tropical diseases that decimated the French soldiers.[6]

In the 18th century, the Sihanaka were vassals of the Boina Kingdom. They mounted at least one major attack against the Boina in an attempt to regain independence, but were unsuccessful. The high number of slaves possessed by the Sihanaka led to a spate of slave revolts in 1768 that they requested European assistance to quell.[5] Around 1800 the territory was conquered by the armies of the Kingdom of Imerina under the leadership of King Andrianampoinimerina. This led to a massive inflow of Merina colonists who settled among the Sihanaka and introduced a variety of cultural, economic and political practices that were assimilated into the local culture to the extent that by the mid-19th century "it resembled a Merina province".[7] The Sihanaka resented this imposition and held the Merina sovereigns in low regard.[8]

The 1895 capture of the Merina royal capitol, the Rova of Antananarivo, by the French sparked the Menalamba rebellion against foreigners, Christianity and Merina domination. In the chaotic 1895–97 period, bands of Sakalava, Marofotsy and other bandits engaged in raids to loot cattle and other goods. The Sihanaka were especially hard hit owing to their reputation as a relatively wealthy trading people. Many Sihanaka villagers resorted to sleeping in the forests and fields to avoid falling victim to nighttime pillage and arson; entire Sihanaka villages were burned.[9]

Following French colonization of the island in 1897, the colonial administration imposed a heavy burden of corvée (statute labor) on the Sihanaka in the 1910s, requisitioning them for minimal to no pay to build the railroad linking the coastal port of Toamasina to the capital city.[10]

Today, the Sihanaka heavily cultivate the land around Laka Alaotra and have increasingly drained the swamps to make way for farming using heavy machinery.[1] This loss of habitat has posed a threat to species living in the area, including the critically endangered Lac Alaotra bamboo lemur, the only lemur species on the island to have evolved to live in and eat the papyrus reeds bordering the lake.[11]

Family and society

In 2013, the Sihanaka were estimated to number around 200,000.[12] Families are hierarchical, with parents exercising authoritarian control over their children.[13] Sihanaka men and women have significant autonomy in deciding when to marry and whether to divorce. Marriages are disallowed between siblings, cousins, and direct ascendents.[14] To reinforce this forbidden physical intimacy, Sihanaka have historically used a formal term of address when speaking to these particular family members.[15] Mothers are traditionally subject to several fady, such as not being allowed to look at dead infants, eat veal, or eat a particular type of banana once their child had learned to say the word for it.[16] Parents were traditionally responsible for educating their own children, and while today those who can afford a formal education will study at school, parents and the broader community remain collectively engaged in educating children into social and cultural norms and practices.[4] Male children are circumcised by their families no later than the age of seven.[17]

Among the Sihanaka, communities are led by their eldest members, termed Tangalamena or Zokiolona.[13] Social relations are guided by the principle of fihavanana (solidarity, goodwill).[4] Although the Sihanaka never developed a centralized kingdom like their western neighbor, the Kingdom of Imerina,[5] the Sihanaka were historically united around their traditional religious beliefs.[7]

Religious affiliation

The traditional beliefs of the Sihanaka, as elsewhere in Madagascar, revolve around respect for a creator god (Zanahary), the ancestors, and fady (ancestral interdictions). Aspects of ancestor worship among the Sihanaka include joro (collective prayers said to invoke the blessings of God or the ancestors), burial in family tombs, the famadihana reburial ceremony, and the sanctification of particular stones (tsangambato), land (tany masina), and shrines (doany, tony and jiro).[17] Another major element of this tradition is the role of ambalavelona, believed to be the spirits of the ancestors themselves. Each ancestral practice or tradition has a particular spirit associated with it, and the Sihanaka show respect for these spirits by maintaining ancestral customs and traditions and adhering to fady.[17]

The Sihanaka share the belief common throughout the island that the spirits of ancestors can possess the living, placing them in a trance state called a tromba. The Sihanaka traditionally believe that looking at a cuckoo roller (an indigenous bird) will induce the tromba.[18] Communities look to ombiasy (wise men) for spiritual guidance, to commune with the ancestors, and to determine which days are auspicious for undertaking particular tasks or endeavors.[4] By the 1600s, a uniform religious belief system had grown around a group of sampy (idols) believed to channel the protective spiritual power of 11 deities. The origin of these amulets is said to have been in the western territories under Sakalava control.[5]

The Christian conversion of the Merina royal court in 1869 spurred the arrival of Merina missionaries in Sihanaka country and the conversion of a significant portion of the population. Following the French capture of the Merina capital in 1895, Christianity was largely abandoned in Sihanaka and traditional religious beliefs regained preeminence; at least one major historic church in the area was burned.[9] French Catholic missionaries arrived in the area around 1900 and gradually began converting members of local communities.[19] This was soon followed by a renewed effort on the part of Protestant missionaries, leading to further conversions. Today, traditional beliefs remain strong among the Sihanaka, although a growing number practice orthodox Christianity or a syncretic form that incorporates aspects of traditional respect for ancestors and their norms.[4]

Culture

European visitors in 1667 reported the Sihanaka lived in fortified villages, which they very effectively defended with bows and arrows. They were the only ethnic group encountered by the European party that had built a bridge.[5] Homes were made of plant material; the Sihanaka believed building homes in brick or clay would invite the displeasure of the ancestors.[20] Gendered roles factored into house construction and maintenance: men applied carpentry to build the frame of the house and roof, as well as the windows and doors and their frames, while women wove zozoro reed mats that would serve as walls, flooring and roofing.[21]

The principal food eaten in Sihanaka has long been rice, which they cultivate heavily. The rice based diet was supplemented by a wide range of game and other meats, including lemurs, wild boars, snakes, owls, rats, cats and crocodile, the latter having at one time been protected by a fady that was eventually abandoned.[22] Use of tobacco or marijuana[21] and consumption of pork[23] were commonly forbidden in Sihanaka families.[21] Many believed that transporting swine across Lake Alaotra would bring storms.[24] Their traditional dress consisted of clothing woven of raffia fibers.[25]

The traditional martial art of moraingy, particularly common among Sakalava communities, was historically common among the Sihanaka.[26]

Fady

Sihanaka culture traditionally adhered to a wide variety of fady, some of which are still respected to varying degrees by more traditional families to the present day. Many of their fady in the early 1900s were documented by historian Van Gennep. The most absolute fady and the only one that was seemingly practiced by all Sihanaka was a prohibition against working in a paddy field on Tuesdays; sub-groups among the Sihanaka also practiced other taboos associated with particular days of the week, such as not leaving the house or not cleaning floor mats on certain days.[27] A fady was placed on consumption of any new or foreign products, including Western medicines.[28] Another common fady was a taboo against watching the rising or setting of the sun, staring at anything red, or falling asleep at sunset.[29]

Fady have served to protect certain wildlife in the Sihanaka homeland. The aye-aye is the subject of numerous fady and folk tales among the Sihanaka. It was traditionally believed that a person who fell asleep in the forest might be brought a pillow by an aye-aye. If the pillow was for one's head, he or she would become rich, but if it was for the feet, that person would be subject to evil sorcery.[30] Similarly, the indri is considered sacred and may not be hunted, killed or eaten.[31]

Funeral rites

The Sihanaka traditionally believed that death was always associated with a contagion that could be passed to family members of the deceased. This belief is reflected in traditional funeral rites. A second door to the family home was used uniquely for carrying out the body of the deceased.[32] Before the body was removed, the widow of the deceased would dress in a fine red lamba and put on all her jewelry, then watch the procession from her seat at the main entryway to her house.[33] The villagers carried the body to a house where the village women would gather, and the female family members would weep while the other women would play drums and recite prayers. The men would stay in a separate house (called the tranolahy, or "men's house") where they would prepare a feast of cooked meat and rum, which they would periodically deliver to the women mourners. Occasionally a selected man would circle the house and sing a funeral chant, with the women inside interjecting in call-and-response.[34] After the feast, a community leader would dip his finger in melted fat and touch those who had assisted in the funeral, to protect them against illness and from being followed by malevolent spirits.[35]

Family members of the deceased would then reunite in the family home where they would drink more rum and carry out a ritual of purification (faly ranom-bohangy). Lemon or lime leaves and two other herbs were soaked in a bowl of water, and a family member whose parents were still living would be chosen to sprinkle it on the deceased's possessions, enabling them to be redistributed and reused.[35] The door by which the corpse had been removed was then locked for eight days, during which time the family was required to fast. After completion of this fasting period, the family underwent a purification ritual (afana) and the second door was unlocked.[32] Another feast was observed to formally end the period of community purification.[36] The home of the deceased was then allowed to fall into ruin.[32]

The villagers would afterward return to the house of the widow, pull off her lamba and jewelry, uncomb her hair (a sign of mourning), dress her in an old lamba, require her to eat only using a broken spoon and plate they provided, and cover her in a rotting mat which she was forbidden to remove until nightfall. She was required to maintain this mourning state for at least eight months, during which time she was forbidden to wash or speak to others during daylight hours. After this period she could abandon the mourning ritual and was considered "divorced" (i.e. free to remarry and visit her own parents and family members, previously forbidden); however, if the parents of her deceased husband were still living, only they could declare her divorced, and she was indefinitely required to remain unmarried and forbidden from visiting family if this status was not granted by them. This practice of declaring divorce, without the mourning ritual, was also applied in the event of separation from a living spouse.[33]

Language

The Sihanaka speak a dialect of the Malagasy language, which is a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language group derived from the Barito languages, spoken in southern Borneo.[37]

Economy

By the mid-1600s, the Sihanaka had already established themselves as one of the island's most important trading groups. Their location on the main trade route between the coast and the Merina capital of Antananarivo enabled them to become important trading partners beginning in the 18th century; slave trading was a major source of income until outlawed under Radama I in the 1810s.[5] The Sihanaka women also produced pottery, which was baked using wood collected by men in the surrounding forests.[38]

Since the end of slave trading, the Sihanaka largely derived their livelihoods from rice farming. Their region is among the most productive on the island.[39] Wealth is unequally distributed, with the wealthy owning the majority of the fertile land, which is either rented to the poor or worked by them for low wages.[13]

Members of this community also herd zebu and catch fish in Lake Alaotra.[39] The work of fishing was traditionally subdivided by gender: men were only allowed to fish for eels, while women were tasked to use nets to catch small fish, and children were the only ones allowed to fish using poles. Men and children would traditionally leave their catch on the shore for women to pick up and take back to the village.[38]

The Sihanaka are one of the few Malagasy groups who historically branded their cattle.[40] This was done by clipping the ear of the cow and was a religious act conducted once annually on a dedicated day of feasting.[41] Cattle generally belonged to the community as a whole and were used principally to assist with farming.[42]

Notes

- Bradt & Austin 2007, p. 27.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 113.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 108.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 114.

- Ogot 1992, p. 431.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 109.

- Ellis & Rajaonah 1998, p. 70.

- Ellis & Rajaonah 1998, p. 89.

- Ellis & Rajaonah 1998, p. 108.

- Fremigacci 2014, pp. 190-199.

- Mutschler, T. (1999). "Folivory in a Small-Bodied Lemur". In Berthe Rakotosamimanana; Hanta Rasamimanana; Jörg U. Ganzhorn; Steven M. Goodman (eds.). New Directions in Lemur Studies. pp. 221–239. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4705-1_13. ISBN 978-1-4613-7131-1.

- Diagram Group 2013.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 103.

- Gennep 1904, p. 163.

- Gennep 1904, p. 165.

- Gennep 1904, p. 169.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 115.

- Gennep 1904, p. 265.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 141.

- Gennep 1904, p. 39.

- Gennep 1904, p. 299.

- Gennep 1904, p. 209.

- Gennep 1904, p. 225.

- Gennep 1904, p. 196.

- Condra 2013, p. 455.

- Cipollone 2008, p. 137.

- Gennep 1904, p. 203.

- Gennep 1904, p. 37.

- Gennep 1904, p. 55.

- Gennep 1904, p. 223.

- Gennep 1904, p. 199.

- Gennep 1904, p. 64.

- Gennep 1904, p. 61.

- Gennep 1904, p. 158.

- Gennep 1904, p. 74.

- Gennep 1904, p. 75.

- Adelaar & Himmelmann 2005, p. 456.

- Gennep 1904, p. 155.

- Thompson & Adloff 1965, p. 264.

- Gennep 1904, p. 188.

- Gennep 1904, p. 193.

- Gennep 1904, p. 190.

Bibliography

- Adelaar, K Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus (2005). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9781136755095.

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-1-84162-197-5.

- Cipollone, Giulio (2008). Christianisme et droits de l'homme à Madagascar: un siècle d'évangélisation dans la région Alaotra-Mangoro (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-2-8111-0041-4.

- Condra, Jill (2013). Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing Around the World. Los Angeles: ABC Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-37637-5.

- Diagram Group (2013). Encyclopedia of African Peoples. San Francisco, CA: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-96341-5.

- Ellis, Stephen; Rajaonah, Faranirina (1998). L'insurrection des menalamba: une révolte à Madagascar, 1895–1898 (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-796-1.

- Fremigacci, Jean (2014). Etat, économie et société coloniale à Madagascar: De la fin du XIXe siècle aux années 1940 (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0984-4.

- Gennep, A.V. (1904). Tabou Et Totémisme à Madagascar (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. ISBN 978-5-87839-721-6.

- Ogot, Bethwell (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-101711-7.

- Thompson, Virginia; Adloff, Richard (1965). The Malagasy Republic: Madagascar today. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0279-9.