Siege of Kijevo (1991)

The 1991 siege of Kijevo was one of the earliest conflicts in the Croatian War of Independence. The 9th Corps of the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija – JNA) led by Colonel Ratko Mladić and the forces of the Serbian Autonomous Oblast (region) of Krajina (SAO Krajina) under Knin police chief Milan Martić besieged the Croat-inhabited village of Kijevo in late April and early May 1991. The initial siege was lifted after negotiations that followed major protests in Split against the JNA.

| Siege of Kijevo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||

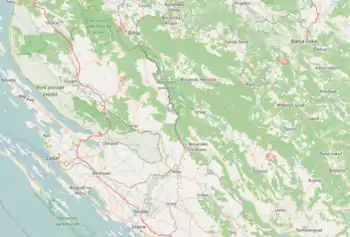

The location of Kijevo within Croatia. Areas controlled by the JNA in late December 1991 are highlighted in red. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| unknown | 58 policemen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

20 captured 2 wounded | ||||||

The JNA and the SAO Krajina forces renewed the blockade in mid-August. Kijevo was captured on 26 August, and subsequently looted and burned. The fighting in Kijevo was significant as one of the first instances when the JNA openly sided with the SAO Krajina against Croatian authorities. The Croatian police fled Kijevo towards the town of Drniš and the remaining Croatian population left the village.

Martić was tried at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) on several different charges of war crimes including, his involvement in the siege of Kijevo. The trial resulted in a guilty verdict, and the findings of the Trial Chamber regarding Kijevo, made in 2007, were confirmed by the ICTY Appeals Chamber in 2008, based on witness testimonies about it being ethnic cleansing. The siege was the first instance of use of the ethnic cleansing in the Yugoslav Wars. Croatian authorities tried Mladić in absentia and convicted him for war crimes committed in Kijevo.

Background

In 1990, ethnic tensions between Serbs and Croats worsened after the electoral defeat of the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia by the Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica, HDZ). The Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija – JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence (Teritorijalna obrana – TO) weapons to minimize resistance.[1] On 17 August, the tensions escalated into an open revolt of the Croatian Serbs,[2] centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Knin (approximately 60 kilometres (37 miles) north-east of Split),[3] parts of the Lika, Kordun, Banovina and eastern Croatia.[4] Serbia, supported by Montenegro and Serbia's provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo, unsuccessfully tried to obtain the Yugoslav Presidency's approval for a JNA operation to disarm Croatian security forces in January 1991.[5] The request was denied and a bloodless skirmish between Serb insurgents and Croatian special police in March[6] prompted the JNA itself to ask the Federal Presidency to give it wartime authority and declare a state of emergency. Even though the request was backed by Serbia and its allies, the JNA was denied on 15 March. Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, preferring a campaign to expand Serbia rather than to preserve Yugoslavia with Croatia as a federal unit, publicly threatened to replace the JNA with a Serbian army and declared that he no longer recognized the authority of the federal Presidency. The threat caused the JNA to gradually abandon plans to preserve Yugoslavia in favour of expansion of Serbia as the JNA came under Milošević's control.[7] By the end of March, the conflict had escalated to the first fatalities.[8] In early April, leaders of the Serb revolt in Croatia declared their intention to integrate areas under their control with Serbia. These were viewed by the Government of Croatia as breakaway regions.[9]

At the beginning of 1991, Croatia had no regular army. To bolster its defence, Croatia doubled police personnel to about 20,000. The most effective part of the force was 3,000-strong special police deployed in twelve battalions and adopting military organization of the units. There were also 9,000–10,000 regionally organized reserve police set up in 16 battalions and 10 companies. The reserve force lacked weapons.[10] As a response to the deteriorating situation, the Croatian government established the Croatian National Guard (Zbor narodne garde – ZNG) in May by merging the special police battalions into four all-professional guards brigades together consisting of approximately 8,000 troops subordinate to the Ministry of Defence headed by retired JNA General Martin Špegelj.[11] The regional police, by then expanded to 40,000, was also attached to the ZNG and reorganized in 19 brigades and 14 independent battalions. The guards brigades were the only units of the ZNG that were fully armed with small arms; throughout the ZNG there was a lack of heavier weapons and there was no command and control structure.[10] The shortage of heavy weapons was so severe that the ZNG resorted to using World War II weapons taken from museums and film studios.[12] At the time, Croatian stockpile of weapons consisted of 30,000 small arms purchased abroad and 15,000 previously owned by the police. A new 10,000-strong special police was established then to replace the personnel lost to the guards brigades.[10]

Prelude

In 1991, Kijevo was a village of 1,261 people, 99.6% of whom were Croats. It was surrounded by the Serb villages of Polača, Civljane and Cetina.[13][14] Following the Log revolution, the three Serb villages had become part of the SAO Krajina and road access to Kijevo was restricted as barricades were set up in Polača and Civljane on the roads serving the village.[15] In response, its population set up an ad hoc militia.[16]

Following the Plitvice Lakes incident of 1 April 1991, SAO Krajina forces captured three Croatian policemen from nearby Drniš, with the intention of exchanging them for Croatian Serb troops taken prisoner by the Croatian forces at the Plitvice Lakes. In turn, the militia established by the residents of Kijevo captured several Serb civilians and demanded that the captured policemen be released in exchange for their prisoners.[16] On 2 April, JNA intelligence officers reported on this, and warned how local militias in Kijevo and Civljane, otherwise separated by barricades, were engaged in armed skirmishes that threatened to escalate.[16] Kijevo became strategically significant because its location hindered SAO Krajina road communications.[13]

April–May blockade

In the night of 27/28 April, a group of Croatian Ministry of the Interior officers managed to reach Kijevo,[17] and a Croatian police station was formally established in the village on 28 April.[18] The following day,[19] JNA troops, commanded by the JNA 9th (Knin) Corps chief of staff Colonel Ratko Mladić, moved in,[20] cutting all access and preventing delivery of supplies to Kijevo.[13] On 2 May,[21] a Croatian police helicopter made an emergency landing in Kijevo after sustaining damage caused by SAO Krajina troops gunfire. The helicopter was carrying then defence minister Luka Bebić and Croatian Parliament deputy speaker Vladimir Šeks. The aircraft was able to take off after repairs the same day.[22] Another skirmish took place on 2 May on Mount Kozjak, where a member of the SAO Krajina paramilitary was killed while on guard duty.[23]

Croatian President Franjo Tuđman called on the public to bring the siege to an end, and the plea resulted in a large-scale protest against the JNA in Split,[20] organised by the Croatian Trade Union Association in the Brodosplit Shipyard on 6 May 1991.[24] On 7 May, 80 tanks and tracked vehicles and 23 wheeled vehicles of the JNA 10th Motorised Brigade left barracks in Mostar, only to be stopped by civilians ahead of Široki Brijeg, west of Mostar. The convoy remained in place for three days as the crowd demanded that the JNA lift the siege of Kijevo. The protest ended after Alija Izetbegović, the President of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, visited and addressed the protesters, assuring the crowd that the convoy was heading to Kupres rather than Kijevo. Tuđman and Cardinal Franjo Kuharić sent telegrams to the protesters supporting Izetbegović.[25] The siege of Kijevo was lifted through negotiations a few days later, two weeks after the blockade had been imposed.[13]

August blockade

The May arrangement proved short-lived, as the JNA units, again led by Mladić, put up barricades to prevent entry into the village on 17 August 1991. The next day, the Croatian Serb leader Milan Martić laid down an ultimatum to the police and inhabitants of Kijevo, demanding that they leave the village and its vicinity within two days—or face an armed attack.[26][27]

Between 23 and 25 August, Croatian forces evacuated nearly the entire civilian population of the village.[28] On 25 August, Croatian forces launched a failed attack on JNA barracks in Sinj, 38 kilometres (24 miles) to the southeast of Kijevo. The objective of the attack was to obtain weapons, needed as Croatian positions near Kijevo deteriorated.[29]

On 26 August, the JNA attacked Kijevo, opposed by 58 policemen armed with small arms only and commanded by police station chief Martin Čičin Šain. Between 05:18 and 13:00, the JNA fired 1,500 artillery shells against the village, and the Yugoslav Air Force supported the attack with 34 close air support sorties. The same afternoon, the JNA mounted a ground force assault on Kijevo.[30] According to Martić, each house in Kijevo was fired upon.[31] The attacking force consisted of approximately 30 tanks supported by JNA infantry and Croatian Serb militia.[32]

The JNA entered the village by 16:30.[30] Lieutenant Colonel Borislav Đukić, in command of the Tactical Group-1 tasked with capture of Kijevo and the commanding officer of the JNA 221st Motorised Infantry Brigade, reported that the village was secured by 22:30.[33] The Croatian police fled Kijevo in three groups via Mount Kozjak towards Drniš.[30] The remaining Croatian population left after the artillery had destroyed much of their settlements.[34][35] The retreating groups were pursued by the Yugoslav Air Force jets as they made their way across the Kozjak.[36] Radio Television Belgrade reporter Vesna Jugović recorded these events. Krajina units commanded by Martić acted in concert with JNA to take command of the area.[37]

Aftermath

The clash between the Croatian forces and the JNA in Kijevo was one of the first instances where the JNA openly sided with the insurgent Serbs in the rapidly escalating Croatian War of Independence,[34] acting based on Martić's ultimatum.[31] The defending force suffered only two wounded, but one of the retreating groups was captured.[30] The group, consisting of 20 men,[38] were later released in a prisoner of war exchange.[30] The JNA suffered no casualties.[33] After the JNA secured Kijevo, the village was looted and torched.[32][36] The destruction of Kijevo became one of the most notorious Serb crimes in the early stages of the war.[39] The JNA units which took part in the fighting in and around Kijevo advanced towards Sinj in the following few days, capturing Vrlika before being redeployed to take part in the Battle of Šibenik in mid-September.[32]

At the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, the trial of Milan Martić resulted in a guilty verdict with regard to Martić's involvement on Kijevo, and the findings of the Trial Chamber in 2007 regarding Kijevo were confirmed by the Appeals Chamber in 2008, based on witness testimonies about it being ethnic cleansing.[28] The siege of Kijevo was the first instance of application of the strategy of ethnic cleansing in the Yugoslav Wars.[40] The events at Kijevo were not included in the indictment at the trial of Ratko Mladić, but the Croatian judiciary tried Mladić in absentia for war crimes committed in Kijevo. He was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison.[41]

References

- Hoare 2010, p. 117.

- Hoare 2010, p. 118.

- The New York Times & 19 August 1990.

- ICTY & 12 June 2007.

- Hoare 2010, pp. 118–119.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 384–385.

- Hoare 2010, p. 119.

- Engelberg & 3 March 1991.

- Sudetic & 2 April 1991.

- CIA 2002, p. 86.

- EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- Ramet 2006, p. 400.

- Gow 2003, p. 154.

- Silber & Little 1996, p. 171.

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 18 August 2010.

- Hrvatski vojnik & October 2012.

- Municipality of Kijevo 2007.

- Degoricija 2008, p. 49.

- Hrvatski vojnik & May 2009.

- Woodward 1995, p. 142.

- FBIS & 2 May 1991, p. 38.

- Nacional & 22 August 2005.

- Ružić 2011, p. 411.

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 6 May 2001.

- Lučić 2008, p. 123.

- Gow 2003, pp. 154–155.

- Allcock, Milivojević & Horton 1998, p. 142.

- ICTY & 12 June 2007, pp. 61–62.

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 25 August 2010

- Deljanin & 27 May 2011.

- Armatta 2010, p. 397.

- Novosti & 3 June 2011.

- JNA & 27 August 1991.

- Gow 2003, p. 155.

- Silber & Little 1996, pp. 171–173.

- Magaš 1993, p. 320.

- Silber & Little 1996, p. 172.

- ICTY & 12 June 2007, p. 107.

- Hoare 2010, p. 122.

- Gow 2003, p. 120.

- Jutarnji list & 26 May 2011.

Sources

- Books and scientific papers

- Allcock, John B.; Milivojević, Marko; Horton, John Joseph (1998). Conflict in the former Yugoslavia: an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780874369359.

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 9780160664724. OCLC 50396958.

- Degoricija, Slavko (2008). Nije bilo uzalud (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: ITG - Digitalni tisak. p. 49. ISBN 978-9537167172.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Gow, James (2003). The Serbian Project and Its Adversaries: A Strategy of War Crimes. London, England: C. Hurst & Co. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9781850656463.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 9781139487504.

- Lučić, Ivica (June 2008). "Bosna i Hercegovina od prvih izbora do međunarodnog priznanja" [Bosnia and Herzegovina from the First Elections to the International Recognition]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 40 (1): 107–140. ISSN 0590-9597.

- Magaš, Branka (1993). The Destruction of Yugoslavia: Tracking the Break-up 1980-92. New York City: Verso Books. ISBN 9780860915935.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ružić, Slaven (December 2011). "Razvoj hrvatsko-srpskih odnosa na prostoru Benkovca, Obrovca i Zadra u predvečerje rata (ožujak - kolovoz 1991. godine)" [Development of Croatian-Serbian relations in Benkovac, Obrovac and Zadar area in the eve of the war (March-August 1991)]. Journal - Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian History. 43 (1): 399–425. ISSN 0353-295X.

- Silber, Laura; Little, Allan (1996). The death of Yugoslavia. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140261684.

- Woodward, Susan L. (1995). Balkan Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution After the Cold War. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780815795131.

- News reports

- Cvitić, Plamenko (22 August 2005). "Nisam imao konkurenciju za Irak" [I had no competition for Iraq] (in Croatian). Nacional.

- Deljanin, Zorana (27 May 2011). "Posljednji zapovjednik obrane Kijeva Martin Čičin Šain: Moj susret s Mladićem" [The last Kijevo defence commander, Martin Čičin Šain: My encounter with Mladić]. Novi list (in Croatian).

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- Jurković, Marina (18 August 2010). "APEL SABORU: Proglasiti 17. 8. danom početka rata" [APPEAL TO SABOR: Declare 17 August the day when the war began]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Kosanović, Saša (3 June 2011). "Mnogo pitom Mladić" [Very tame Mladić]. Novosti (in Croatian).

- Paštar, Toni (25 August 2010). "Vijenci, svijeće i molitve u Sinju i Vrlici za poginule branitelje" [Wreaths, candles and prayers for dead in Sinj and Vrlika]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Pavić, Snježana (26 May 2011). "Za više od 100 ubijenih Hrvata Škabrnji i Saborskom Ratko Mladić neće odgovarati. Nitko ga nije optužio!" [Ratko Mladić will not be held accountable for more than 100 Croats killed in Škabrnja and Saborsko. Nobody charged him!]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian).

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- Šetka, Snježana (6 May 2001). "Dan kada je ustao Split" [Day when Split rose up]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- ""Terrorists" Fire on Croatian Helicopter". Daily Report: East Europe (78–88). Foreign Broadcast Information Service. Tanjug. 1991. OCLC 16394067.

- Other sources

- "Domovinski rat". Official website (in Croatian). Municipality of Kijevo. 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Đukić, Borislav (27 August 1991). "Izvješće 221. mtbr. Komandi 9. korpusa OS SFRJ o stanju u TG-1, posljednjim borbama u osvajanju Kijeva, borbama oko sela Lelasi te napredovanju prema Vrlici i Otišiću" [Report of the 221st MotBde to the command of the 9th Corps of the armed forces of the SFR Yugoslavia regarding conditions in the TG-1, the final battles to capture Kijevo, fighting around village of Lelasi and advance towards Vrlika and Otišić] (PDF) (in Serbian). pp. 266–267.

- Nazor, Ante (May 2009). "Iz izvješća "Organu bezbednosti Komande RV i PVO" JNA o događajima u Borovu Selu - 2. svibnja 1991. (I. dio)" [From reports to the Security services of Yugoslav Air Force and Air Defence on events in Borovo Selo - 2 May 1991]. Hrvatski vojnik (in Croatian and Serbian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (239). ISSN 1333-9036.

- Nazor, Ante (October 2012). "Pokušaj uvođenja izvanrednog stanja u Hrvatsku - izvješća "organa bezbednosti" JNA od 2. travnja 1991" [An attempt to introduce the state of emergency in Croatia - JNA security service reports of 2 April 1991]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian and Serbian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (406). ISSN 1333-9036.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.