Short octave

The short octave was a method of assigning notes to keys in early keyboard instruments (harpsichord, clavichord, organ), for the purpose of giving the instrument an extended range in the bass range. The rationale behind this system was that the low notes F♯ and G♯ are seldom needed in early music. Deep bass notes typically form the root of the chord, and F♯ and G♯ chords were seldom used at this time. In contrast, low C and D, both roots of very common chords, are sorely missed if a harpsichord with lowest key E is tuned to match the keyboard layout. A closely related system, the broken octave, added more notes by using split keys: the front part and the back part of the (visible) key controlled separate levers and hence separate notes.

Short octave

First type

In one variant of the short octave system, the lowest note on the keyboard was nominally E, but the pitch to which it was tuned was actually C. Nominal F♯ was tuned to D, and nominal G♯ was tuned to E. Thus, in playing the keys:

- E F♯ G♯ F G A B C

the player would hear the musical scale of C major in the bass:

- C D E F G A B C

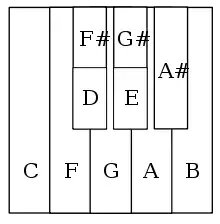

The actual note assignments can be seen in the following diagram, which shows the lowest eight keys of an early keyboard:

The rationale behind this system was that the low notes F♯ and G♯ are seldom needed in early music. Deep bass notes typically form the root of the chord, and F♯ and G♯ chords were seldom used at this time. In contrast, low C and D, both roots of very common chords, are sorely missed if a harpsichord with lowest key E is tuned to match the keyboard layout. When scholars specify the pitch range of instruments with this kind of short octave, they write "C/E", meaning that the lowest note is a C, played on a key that normally would sound E.

Second type

A second type of short octave used the keys

- B C♯ D♯ C D E F♯ G

to play the G major scale

- G A B C D E F♯ G.

Here, the exotic bass notes C♯ and D♯ are sacrificed to obtain the more essential A and B. The notation for the pitch range of such an instrument is "G/B". The following diagram illustrates this kind of short octave:

In stringed instruments like the harpsichord, the short octave system created a defect: the strings which were tuned to mismatch their keyboard notes were in general too short to sound the reassigned note with good tone quality. To reach the lower pitch, the strings had to be thickened, or tuned too slack. During the 17th and 18th centuries, harpsichord builders gradually increased the size and bass range of their instruments to the point where every bass note could be properly played with its own key.

Short octaves were very common in the early organ. Here, the practice would not have yielded poor tone quality (since the associated pipes would have to be built with the correct length in any event). Far more than on stringed instruments the financial savings would have been quite considerable, as the long pipes entailed quite an expense, even in materials alone. But as harmonic music developed more complexity in the late 17th and 18th centuries and the desire arose for completely chromatic bass octaves, short octaves ultimately came to be abandoned in organs as well.

History

The 18th-century author Quirinus van Blankenburg suggested that the C/E short octave originated as an extension of keyboards that went down only to F; the addition of just one key (nominal E) and the reassignment of the F♯ and G♯ added three new notes to the bass range. Van Blankenburg says that when the short octave was invented, it was called the "new extension" for this reason.[1] According to Frank Hubbard, harpsichords and organs of the 16th and 17th centuries "almost always" had short octaves.[2]

Edward Kottick notes that the short octave persisted for a long time, suggests that a kind of mutual inertia between composers and instrument builders may have been responsible:

Our forebears were much more practical than we are. Since nobody wrote music that required those notes, why go to the expense of putting them in? And what composer would bother to write them if few keyboard instruments had them?[3]

A transitional stage toward the final adoption of chromatic keyboards was seen in certain English virginals of the later 17th century. On these the lowest key could pluck two different strings, depending on the slot in which its jack was placed. One of these strings was tuned to low G (the normal pitch of this key in the G/B short octave) and the other to whatever missing chromatic pitch was desired. The player could then move the jack to the slot that provided the desired note, according to the piece being played.[4]

Broken octave

A variant of the short octave added more notes by using split keys: the front part and the back part of the (visible) key controlled separate levers and hence separate notes. Assume the following keys:

- E F F♯ G G♯ A

with both F♯ and G♯ split front to back. Here, E played C, the front half of the F♯ key played D, and the (less accessible) rear half played F♯. The front half of the G♯ key played E, and the rear half played G♯. As with the short octave, the key labeled E played the lowest note C. Thus, playing the nominal sequence

- E F♯(front) G♯(front) F F♯(back) G G♯(back) A

the player would hear:

- C D E F F♯ G G♯ A

The actual note assignments can be seen in the following diagram:

It can be seen that only two notes of the chromatic scale, C♯ and D♯, are missing. An analogous arrangement existed for keyboards with G instead of C at the bottom.

According to Trevor Pinnock,[5] the short octave is characteristic of instruments of the 16th century. He adds, "in the second half of the 17th century, when more accidentals were required in the bass, 'broken octave' was often used."

Viennese bass octave

The short/broken octave principle not only survived, but was even developed further in one particular location, namely Vienna. The "Viennese bass octave" (German: "Wiener Bass-oktave") lasted well into the second half of the 18th century. Gerlach (2007) describes this keyboard arrangement as follows:

The notes leading down to F1 were accommodated on the keys of a "short-scaled octave" from c to C (only F♯1 and G♯1, as well as C♯ and E♭ continued to be omitted.[6]

The assignment of notes to keys, which strikingly included a triple-split key, was as shown in the following diagram, adapted from Maunder (1998):

Maunder (who uses the term "multiple-broken short octave") observes that the Viennese bass octave, like its predecessors, imposed distortions on the string scaling of the harpsichord: it "leads to extreme foreshortening of the scale in the bass." Hence, it required unusually thick strings for the bottom notes, on the order of 0.6 to 0.7 mm (0.024 to 0.028 in).[7]

The Viennese bass octave gradually went out of style. However, Maunder notes instruments with Viennese bass octave built even in 1795, and observe that advertisements for such instruments appear even up to the end of the century.[8]

Music written specifically for short-octave instruments

While the short octave seems primarily to have been an economy measure, it does have the advantage that the player's left hand can in certain cases span a greater number of notes. The composer Peter Philips wrote a pavane in which the left hand plays many parallel tenths. This is a considerable stretch for many players, and become even harder when (as in Philips's pavane), there sometimes other notes included in the chord. Of this piece harpsichord scholar Edward Kottick writes, "The sensuality of effortlessly achieving tenths is so strong, so delightful, that one cannot really claim to know the piece unless it has been played on a short-octave keyboard."[9]

A later composer who wrote music conveniently playable only on a broken-octave instrument was Joseph Haydn, whose early work for keyboard was intended for harpsichord, not piano.[6] As Gerlach (2007) points out, Haydn's "Capriccio in G on the folk song 'Acht Sauschneider müssen sein'", H. XVII:1 (1765) is evidently written for a harpsichord employing the Viennese bass octave. The work terminates in a chord in which the player's left hand must cover a low G, the G an octave above it, and the B two notes higher still. On orthodox keyboards this would be an impossible stretch for most players, but as on the Viennese bass octave it would have been easy to play, with the fingers depressing keys that visually appeared as D–G–B (see diagram above).

When Haydn's Capriccio was published by Artaria in the 1780s, the Viennese bass octave had mostly disappeared (indeed, the harpsichord itself was becoming obsolete). The publisher accordingly included alternative notes in the places where the original version could be played only on a short octave instrument, presumably to accommodate the needs of purchasers who owned a harpsichord or piano with the ordinary chromatic bass octave.[6]

References

Notes

- Quoted from Hubbard (1967, 237)

- Hubbard (1967, 5)

- Kottick (1992, 32)

- Hubbard (1967, 151 fn.)

- Pinnock, Trevor (1975) "Buying a Harpsichord – 1", Early Music, 126–131.

- Gerlach (2007, VII)

- Maunder (1998, 44)

- Maunder (1998, 47)

- Reference for Philips as well as quotation: Kottick (2003, 40). The full Pavane may be found starting on p. 321 of the Maitland/Squire edition of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, cited below. Maitland and Squire likewise noticed (pp. xvii-xviii) that Philips's works require a short-octave instrument and indeed there two other pieces by Philips in this work (pp. 286, 327) of this type.

Sources

- Gerlach, Sonja (2007) Haydn: Klavierstücke/Klaviervariationen [keyboard pieces/keyboard variations]. Henle Verlag.

- Hubbard, Frank (1967) Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; ISBN 0-674-88845-6.

- Kottick, Edward L. (1992) The harpsichord owner's guide: a manual for buyers and owners. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-4388-1.

- Kottick, Edward L. (2003) A history of the harpsichord. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Maitland, J. A. Fuller and W. Barclay Squire, eds. (1899). The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. Reprinted 1963 by Dover Publications, New York.

- Maunder, Richard (1998) Keyboard Instruments in Eighteenth-century Vienna. Oxford: Oxford University Press.