Senecio congestus

Senecio congestus, also known by its common names swamp ragwort, northern swamp groundsel, marsh fleabane, marsh fleawort, clustered marsh ragwort and mastodon flower, a herbaceous member of the family Asteraceae and the genus Senecio, can be seen most easily when its bright yellow umbel flowers appear from May to early July standing 3 to 4 feet (0.9 to 1.2 m) along marshes, stream banks and slough areas where it likes to grow.[4][5][6]

| Senecio congestus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Senecio |

| Species: | S. congestus |

| Binomial name | |

| Senecio congestus | |

| |

| Range of S. congesta | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cineraria congesta R. Br. | |

Description

Like many of the Senecio genus S. congestus can be an annual or biennial and perhaps rarely perennial, depending on the conditions.[2] A villous broad leafed plant with a single[7] hollow stem and favoring mud flats like Marsh Groundsel (Senecio hydrophilus) but not alike in that marsh ragwort cannot tolerate alkaline sites nor standing water.[8]

In the early stages of growth, the leaves, stem, and flower heads are all covered with translucent hairs, producing a "greenhouse effect" close to the surface of the plant, essentially extending the growing season by a few vital days by allowing the sun to warm the tissues, and preventing the heat from escaping.[9]

Leaves and stems: An erect plant [7] standing 6 to 60 inches (15 to 150 cm) tall, S. congestus varies as much in stature as it does in the distribution and the persistence of its tomentum (the closely matted or fine hairs on plant leaves).[2] Sparse to dense villous stems are more hollow towards the base;[8] hairs that are white, light yellowish, or reddish brown.[2] Basal and cauline[2] leaf edges mostly toothless or with a few coarse teeth[7] that sometimes wither before flowering.[2] The leaves all basically similar in shape, oblong with the lower ones often spatulate, 1.6 to 8 inches (4 to 20 cm) long, 0.2 to 2.5 in (0.5 to 6 cm) wide, with the basal leaves occasionally larger, glabrous or villous in patches, rounded at the tips, toothed, often deciduous with clasping bases.[8]

Flowers: "Congested" clusters of several to many pale yellow flower heads[8] that sometimes appear tubular and incompletely opened.[2] a branched inflorescence,[7] with 13 to more than 21 flower heads per stalk. Each flower head is ¼ to ½ inch (6 to 13 mm) across and 0.16 to 0.4 inch (0.4 to 10 mm) in length,[2] with small but obvious rays[7] in a corolla laminae surrounded by (usually) 21 green or yellowish green, pink tipped bracts[2] which can be scarious toward the tips.[8]

Seeds: Typical of the genus Senecio, S. congestus produces strongly accrescent[8] one-seeded, one-celled,[2] 1.5 to 2.5 millimetres long[8] dry achenes[7] on very fine & numerous,[8] white or dirty white,[2] fluffy,[7] pappus bristles.[8] The seeds have been shown to survive in the soil for more than a year but less than 5 years, the maximum longevity unknown.[10]

Roots: Fibrous and without a tap root.[8]

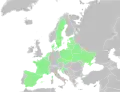

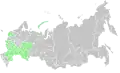

Distribution

Senecio congestus plants itself in areas that have freezing winters[1] and in moist to wet soils, such as damp meadows, swamps, sandy pond edges[7] and roadside ditches[11] at altitudes of 0 to 3,300 feet (1,000 m)[2] It is the most common annual plant species in the eastern Canadian Arctic.[9]

- Native[1][12]

- America

- Asia

- Northwestern Asia: Astrakhan Oblast, Bashkortostan, Belgorod Oblast, Bryansk Oblast, Chuvashia, Franz Josef Land, Kalmykia, Kaluga Oblast, Kirov Oblast or Vyatka, Kursk Oblast, Lipetsk Oblast, Mordovia, Novgorod Oblast, Novaya Zemlya, Orenburg Oblast, Penza Oblast, Perm Krai, Pskov Oblast, Rostov Oblast, Ryazan Oblast, Saint Petersburg, Samara Oblast, Saratov Oblast, Tambov Oblast, Tatarstan, Tula Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Udmurtia, Volgograd Oblast, Voronezh Oblast

- Europe

- Northern Europe: Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Sweden

- Middle Europe: Czech Republic, Poland

- East Europe: Belarus, Kaliningrad Oblast, Lithuania, Ukraine

- West Europe: France, Luxembourg, Netherlands

- Southeastern Europe: Croatia

- Current[1][12]

- America

- Asia

- Northwestern Asia: Astrakhan Oblast, Bashkortostan, Belgorod Oblast, Bryansk Oblast, Chuvashia, Franz Joseph Land, Kalmykia, Kaluga Oblast, Kirov Oblast or Vyatka, Kursk Oblast, Lipetsk Oblast, Mordovia, Novgorod Oblast, Novaya Zemlya, Orenburg Oblast, Penza Oblast, Perm Krai, Pskov Oblast, Rostov Oblast, Ryazan Oblast, Saint Petersburg, Samara Oblast, Saratov Oblast, Tambov Oblast, Tatarstan, Tula Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Udmurtia, Volgograd Oblast, Voronezh Oblast

- Europe

- Northern Europe: Denmark, Estonia (decreasing), Latvia, Sweden

- Middle Europe: Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia

- East Europe: Belarus, Kaliningrad Oblast, Lithuania, Ukraine

- West Europe: Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands

- Southeastern Europe: Croatia

- Southwestern Europe: Andorra, Gibraltar, Spain

- Range maps

Noxiousness and toxicity

Toxicity: Unlike many in the Senecio genus, marsh ragwort is considered a vegetable and safe for human consumption;[13] the young leaves and flowering stems of Senecio congestus can be eaten raw as salad, cooked as a potherb or made into a "sauerkraut",[14]

Noxiousness: Senecio congestus does appear on a list of North Dakota plants to be monitored,[6] however, it tends to be more of a plant the presence of which indicates severe disturbance such as over-foraging and hyper-salinity, as is the case of the habitats of arctic geese where the forage plants are disappearing. Two locations are mentioned by United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) having problems from the ever-expanding populations of arctic geese[15] and one from the Arctic Institute of North America of the University of Calgary[16] or from an unpublished report from the Canadian Wildlife Service made available by the USFWS:[17]

- Akimiski Island in the Canadian Northwest Territories where swards of Puccinellia phryganodes and Carex subspathacea have been replaced with dead willow stands and mudflats growing non-forage plant species, including Glaux maritima and Senecio congestus

- Cape Churchill Region and La Pérouse Bay, Manitoba where the expanding population of lesser snow geese has resulted in substantial changes to all intertidal habitats. In the vicinity of the coast extensive moss carpets are present and Senecio congestus and Salicornia borealis are widespread.

- Karrak Lake,[18] Nunavut where growth in populations of Ross's geese (Chen rossii) and lesser snow geese (Chen caerulescens) has led to a decline in vegetative cover and areas with a 10-year or longer history of goose nesting than in areas with less than 10 years of nesting had more instance of exposed mineral substrate, exposed peat, and Senecio congestus.

Senecio congestus is reported to be extirpated in Michigan.[1]

References

- Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). "PLANTS Profile, Senecio congestus (R. Br.) DC". The PLANTS Database. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- Flora of North America. "Flora of North America Tephroseris palustris (Linnaeus)". Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- The International Plant Names Index. "Details *Othonna palustris L." Plant Names. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- Kershaw, Linda (2003). Saskatchewan Wayside Wildflowers. Edmonton, Alberta: Lone Pine Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 1-55105-354-3.

- Wilkinson, Kathleen (1999). Wildflowers of Alberta A Guide to Common Wildflowers and Other Herbaceous Plants. Edmonton Alberta: Lone Pine Publishing and University of Alberta. p. 284. ISBN 0-88864-298-9.

- NDSU Extension Service. "Swamp ragwort". ND Noxious & Troublesome Weeds. North Dakota State University USDA Cooperative extension service. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

Swamp ragwort has been increasing in frequency recently and infestations should be monitored even though the plant generally is not considered invasive.

- University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. "Senecio congesta". Robert W. Freckmann Herbarium. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- US Geological Survey (2006-08-03). "1. Senecio congestus (R.Br.) DC. -- Swamp ragwort". 14. Senecio L.-- Ragwort; 49. Asteraceae, the Aster Family; Aquatic and Wetland Vascular Plants of the Northern Great Plains. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- S.G. Aiken; M.J. Dallwitz; L.L. Consaul; C.L. McJannet; L.J. Gillespie; R.L. Boles; G.W. Argus; J.M. Gillett; P.J. Scott; R. Elven; M.C. LeBlanc; A.K. Brysting & H. Solstad (2003-05-29). "Tephroseris palustris (L.) Fourr. subsp. congesta (R.Br.) Holub". Flora of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Canadian Museum of Nature. Retrieved 2008-02-23. External link in

|work=(help) - Thompson, K.; Bakker, J.P. & Bekker, R.M. (1997). "The Soil Seed Banks of North West Europe: Methodology, density and Longevity". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- "Senecio congestus (R. Br.) DC / Крестовник скученный" (in Russian). 2005-03-12. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Botanic Garden & Botanical Museum Berlin-Dahlem. "Details for: Tephroseris palustris (L.) Rchb". Euro+Med PlantBase. Freie Universität Berlin. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Tephroseris palustris". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Porsild, A.E. (1953). "Edible Plants of the Arctic": 15–34 (p. 27). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ARCTIC GOOSE HABITAT WORKINGGROUP. "STATUS OF HABITAT AT SELECTED BREEDING AND STAGING SITES". ARCTIC ECOSYSTEMS IN PERIL. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Alisauskas, Ray T.; Charlwood, Jason W.; Kellett, Dana K. (2006-06-01). "Vegetation correlates of the history and density of nesting by Ross's geese and lesser snow geese at Karrak Lake, Nunavut". Encyclopedia.com. HighBeam Research, Gale Group, Farmington Hills, Michigan. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Andrew B. Didiuk; Ray T. Alisauskas; Robert F. Rockwell (2002). "INTERACTION WITH ARCTIC AND SUBARCTIC HABITATS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- "Karrak Lake, Nunavut -- Google Maps". Retrieved 2008-02-24.

External links

Media related to Tephroseris palustris at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tephroseris palustris at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Senecio congestus at Wikispecies

Data related to Senecio congestus at Wikispecies