Latvia

Latvia (/ˈlɑːtviə/ or /ˈlætviə/ (![]() listen); Latvian: Latvija [ˈlatvija]), officially known as the Republic of Latvia (Latvian: Latvijas Republika), is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe.[15][16][17] Since Latvia's independence in 1918, it has been referred to as one of the Baltic states.[18] It is bordered by Estonia to the north, Lithuania to the south, Russia to the east, Belarus to the southeast, and shares a maritime border with Sweden to the west.[19] Latvia has 1,957,200 inhabitants[20] and a territory of 64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi).[21] Its capital and largest city is Riga;[22] other notable major cities in Latvia are Daugavpils, Liepāja, Jelgava, Valmiera, Ventspils and Jūrmala. The country has a temperate seasonal climate.[23] The Baltic Sea moderates the climate, although the country has four distinct seasons and snowy winters.

listen); Latvian: Latvija [ˈlatvija]), officially known as the Republic of Latvia (Latvian: Latvijas Republika), is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe.[15][16][17] Since Latvia's independence in 1918, it has been referred to as one of the Baltic states.[18] It is bordered by Estonia to the north, Lithuania to the south, Russia to the east, Belarus to the southeast, and shares a maritime border with Sweden to the west.[19] Latvia has 1,957,200 inhabitants[20] and a territory of 64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi).[21] Its capital and largest city is Riga;[22] other notable major cities in Latvia are Daugavpils, Liepāja, Jelgava, Valmiera, Ventspils and Jūrmala. The country has a temperate seasonal climate.[23] The Baltic Sea moderates the climate, although the country has four distinct seasons and snowy winters.

Republic of Latvia | |

|---|---|

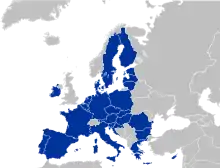

Location of Latvia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Riga 56°57′N 24°6′E |

| Official languages | Latviana |

| Ethnic groups (2019[1]) |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Latvian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Egils Levits | |

| Krišjānis Kariņš | |

| Ināra Mūrniece | |

| Legislature | Saeima |

| Independence from Germany | |

| 18 November 1918 | |

| 26 January 1921 | |

| 7 November 1922 | |

| 21 August 1991 | |

| 1 May 2004 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi) (122nd) |

• Water (%) | 2.09 (as of 2015)[5] |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 1,907,675[6] (147th) |

• 2011 census | 2,070,371[7] |

• Density | 29.6/km2 (76.7/sq mi) (147th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $63.490 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $30,579[8] (43rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $36.771 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $17,230[8] (42nd) |

| Gini (2019) | medium |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 37th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +371 |

| ISO 3166 code | LV |

| Internet TLD | .lvc |

| |

After centuries of German, Swedish, Polish-Lithuanian and Russian rule, a rule mainly executed by the Baltic German aristocracy, the Republic of Latvia was established on 18 November 1918 when it broke away from the German empire and declared independence in the aftermath of World War I.[3] However, by the 1930s the country became increasingly autocratic after the coup in 1934 establishing an authoritarian regime under Kārlis Ulmanis.[24] The country's de facto independence was interrupted at the outset of World War II, beginning with Latvia's forcible incorporation into the Soviet Union, followed by the invasion and occupation by Nazi Germany in 1941, and the re-occupation by the Soviets in 1944 (Courland Pocket in 1945) to form the Latvian SSR for the next 45 years.

The peaceful Singing Revolution, starting in 1987, called for Baltic emancipation from Soviet rule and condemning the Communist regime's illegal takeover.[25] It ended with the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia on 4 May 1990 and restoring de facto independence on 21 August 1991.[26] Latvia is a democratic sovereign state, parliamentary republic. Capital city Riga served as the European Capital of Culture in 2014. Latvian is the official language. Latvia is a unitary state, divided into 119 administrative divisions, of which 110 are municipalities and nine are cities.[27] Latvians and Livonians are the indigenous people of Latvia.[21] Latvian and Lithuanian are the only two surviving Baltic languages.

Despite foreign rule from the 13th to 20th centuries, the Latvian nation maintained its identity throughout the generations via the language and musical traditions. However, as a consequence of centuries of Russian rule (1710–1918) and later Soviet occupation, 26.9% of the population of Latvia are ethnic Russians,[28] some of whom (10.7% of Latvian residents[29]) have not gained citizenship, leaving them with no citizenship at all. Until World War II, Latvia also had significant minorities of ethnic Germans and Jews. Latvia is historically predominantly Lutheran Protestant, except for the Latgale region in the southeast, which has historically been predominantly Roman Catholic.[30] The Russian population is largely Eastern Orthodox Christians.

Latvia is a developed country with an advanced, high-income economy [31][32] and ranks 39th in the Human Development Index.[33] It performs favorably in measurements of civil liberties, press freedom, internet freedom, democratic governance, living standards, and peacefulness. Latvia is a member of the European Union, Eurozone, NATO, the Council of Europe, the United Nations, CBSS, the IMF, NB8, NIB, OECD, OSCE, and WTO. A full member of the Eurozone, it began using the euro as its currency on 1 January 2014, replacing the Latvian lats.[34]

Etymology

The name Latvija is derived from the name of the ancient Latgalians, one of four Indo-European Baltic tribes (along with Couronians, Selonians and Semigallians), which formed the ethnic core of modern Latvians together with the Finnic Livonians.[35] Henry of Latvia coined the latinisations of the country's name, "Lettigallia" and "Lethia", both derived from the Latgalians. The terms inspired the variations on the country's name in Romance languages from "Letonia" and in several Germanic languages from "Lettland".[36]

History

Around 3000 BC, the proto-Baltic ancestors of the Latvian people settled on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea.[37] The Balts established trade routes to Rome and Byzantium, trading local amber for precious metals.[38] By 900 AD, four distinct Baltic tribes inhabited Latvia: Curonians, Latgalians, Selonians, Semigallians (in Latvian: kurši, latgaļi, sēļi and zemgaļi), as well as the Finnic tribe of Livonians (lībieši) speaking a Finnic language.

In the 12th century in the territory of Latvia, there were lands with their rulers: Vanema, Ventava, Bandava, Piemare, Duvzare, Upmale, Sēlija, Koknese, Jersika, Tālava and Adzele.[39]

Medieval period

Although the local people had contact with the outside world for centuries, they became more fully integrated into the European socio-political system in the 12th century.[40] The first missionaries, sent by the Pope, sailed up the Daugava River in the late 12th century, seeking converts.[41] The local people, however, did not convert to Christianity as readily as the Church had hoped.[41]

German crusaders were sent, or more likely decided to go on their own accord as they were known to do. Saint Meinhard of Segeberg arrived in Ikšķile, in 1184, traveling with merchants to Livonia, on a Catholic mission to convert the population from their original pagan beliefs. Pope Celestine III had called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe in 1193. When peaceful means of conversion failed to produce results, Meinhard plotted to convert Livonians by force of arms.[42]

At the beginning of the 13th century, Germans ruled large parts of what is currently Latvia.[41] Together with southern Estonia, these conquered areas formed the crusader state that became known as Terra Mariana or Livonia. In 1282, Riga, and later the cities of Cēsis, Limbaži, Koknese and Valmiera, became part of the Hanseatic League.[41] Riga became an important point of east–west trading[41] and formed close cultural links with Western Europe.[43] The first German settlers were knights from northern Germany and citizens of northern German towns who brought their Low German language to the region, which shaped many loanwords in the Latvian language.[44]

Reformation period and Polish–Lithuanian rule

_en2.png.webp)

Riga became the capital of Swedish Livonia and the largest city in the Swedish Empire.

After the Livonian War (1558–1583), Livonia (Northern Latvia & Southern Estonia) fell under Polish and Lithuanian rule.[41] The southern part of Estonia and the northern part of Latvia were ceded to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and formed into the Duchy of Livonia (Ducatus Livoniae Ultradunensis). Gotthard Kettler, the last Master of the Order of Livonia, formed the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia.[45] Though the duchy was a vassal state to Poland, it retained a considerable degree of autonomy and experienced a golden age in the 16th century. Latgalia, the easternmost region of Latvia, became a part of the Inflanty Voivodeship of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[46]

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden, and Russia struggled for supremacy in the eastern Baltic. After the Polish–Swedish War, northern Livonia (including Vidzeme) came under Swedish rule. Riga became the capital of Swedish Livonia and the largest city in the entire Swedish Empire.[47] Fighting continued sporadically between Sweden and Poland until the Truce of Altmark in 1629[48]. In Latvia, the Swedish period is generally remembered as positive; serfdom was eased, a network of schools was established for the peasantry, and the power of the regional barons was diminished.[49][50]

Several important cultural changes occurred during this time. Under Swedish and largely German rule, western Latvia adopted Lutheranism as its main religion. The ancient tribes of the Couronians, Semigallians, Selonians, Livs, and northern Latgallians assimilated to form the Latvian people, speaking one Latvian language. Throughout all the centuries, however, an actual Latvian state had not been established, so the borders and definitions of who exactly fell within that group are largely subjective. Meanwhile, largely isolated from the rest of Latvia, southern Latgallians adopted Catholicism under Polish/Jesuit influence. The native dialect remained distinct, although it acquired many Polish and Russian loanwords.[51]

Livonia & Courland in the Russian Empire (1795–1917)

The capitulation of Estonia and Livonia in 1710 and the Treaty of Nystad, ending the Great Northern War in 1721, gave Vidzeme to Russia (it became part of the Riga Governorate). The Latgale region remained part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as Inflanty Voivodeship until 1772, when it was incorporated into Russia. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia became an autonomous Russian province (the Courland Governorate) in 1795, bringing all of what is now Latvia into the Russian Empire. All three Baltic provinces preserved local laws, German as the local official language and their own parliament, the Landtag.

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), up to 40 percent of Latvians died from famine and plague.[52] Half the residents of Riga were killed by plague in 1710–1711.[53]

The emancipation of the serfs took place in Courland in 1817 and in Vidzeme in 1819. In practice, however, the emancipation was actually advantageous to the landowners and nobility, as it dispossessed peasants of their land without compensation, forcing them to return to work at the estates "of their own free will".

During these two centuries Latvia experienced economic and construction boom – ports were expanded (Riga became the largest port in the Russian Empire), railways built; new factories, banks, and a University were established; many residential, public (theatres and museums), and school buildings were erected; new parks formed; and so on. Riga's boulevards and some streets outside the Old Town date from this period.

Numeracy was also higher in the Livonian and Courlandian parts of the Russian Empire, which may have been influenced by the Protestant religion of the inhabitants.[54]

National awakening

During the 19th century, the social structure changed dramatically. A class of independent farmers established itself after reforms allowed the peasants to repurchase their land, but many landless peasants remained. There also developed a growing urban proletariat and an increasingly influential Latvian bourgeoisie. The Young Latvian (Latvian: Jaunlatvieši) movement laid the groundwork for nationalism from the middle of the century, many of its leaders looking to the Slavophiles for support against the prevailing German-dominated social order. The rise in use of the Latvian language in literature and society became known as the First National Awakening. Russification began in Latgale after the Polish led the January Uprising in 1863: this spread to the rest of what is now Latvia by the 1880s. The Young Latvians were largely eclipsed by the New Current, a broad leftist social and political movement, in the 1890s. Popular discontent exploded in the 1905 Russian Revolution, which took a nationalist character in the Baltic provinces.

Declaration of independence

World War I devastated the territory of what became the state of Latvia, and other western parts of the Russian Empire. Demands for self-determination were initially confined to autonomy, until a power vacuum was created by the Russian Revolution in 1917, followed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany in March 1918, then the Allied armistice with Germany on 11 November 1918. On 18 November 1918, in Riga, the People's Council of Latvia proclaimed the independence of the new country, with Kārlis Ulmanis becoming the head of the provisional government. The General representative of Germany August Winnig formally handed over political power to the Latvian Provisional Government on 26 November.

The war of independence that followed was part of a general chaotic period of civil and new border wars in Eastern Europe. By the spring of 1919, there were actually three governments: the Provisional government headed by Kārlis Ulmanis, supported by Tautas padome and the Inter-Allied Commission of Control; the Latvian Soviet government led by Pēteris Stučka, supported by the Red Army; and the Provisional government headed by Andrievs Niedra and supported by the Baltische Landeswehr and the German Freikorps unit Iron Division.

Estonian and Latvian forces defeated the Germans at the Battle of Wenden in June 1919,[55] and a massive attack by a predominantly German force—the West Russian Volunteer Army—under Pavel Bermondt-Avalov was repelled in November. Eastern Latvia was cleared of Red Army forces by Latvian and Polish troops in early 1920 (from the Polish perspective the Battle of Daugavpils was a part of the Polish–Soviet War).

A freely elected Constituent assembly convened on 1 May 1920, and adopted a liberal constitution, the Satversme, in February 1922.[56] The constitution was partly suspended by Kārlis Ulmanis after his coup in 1934 but reaffirmed in 1990. Since then, it has been amended and is still in effect in Latvia today. With most of Latvia's industrial base evacuated to the interior of Russia in 1915, radical land reform was the central political question for the young state. In 1897, 61.2% of the rural population had been landless; by 1936, that percentage had been reduced to 18%.[57]

By 1923, the extent of cultivated land surpassed the pre-war level. Innovation and rising productivity led to rapid growth of the economy, but it soon suffered from the effects of the Great Depression. Latvia showed signs of economic recovery, and the electorate had steadily moved toward the centre during the parliamentary period. On 15 May 1934, Ulmanis staged a bloodless coup, establishing a nationalist dictatorship that lasted until 1940.[58] After 1934, Ulmanis established government corporations to buy up private firms with the aim of "Latvianising" the economy.[59]

Latvia in World War II

Early in the morning of 24 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a 10-year non-aggression pact, called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[60] The pact contained a secret protocol, revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern and Eastern Europe were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence".[61] In the north, Latvia, Finland and Estonia were assigned to the Soviet sphere.[61] A week later, on 1 September 1939, Germany and on 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Poland.[62]:32

After the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, most of the Baltic Germans left Latvia by agreement between Ulmanis' government and Nazi Germany under the Heim ins Reich programme.[63] In total 50,000 Baltic Germans left by the deadline of December 1939, with 1,600 remaining to conclude business and 13,000 choosing to remain in Latvia.[63] Most of those who remained left for Germany in summer 1940, when a second resettlement scheme was agreed.[64] The racially approved being resettled mainly in Poland, being given land and businesses in exchange for the money they had received from the sale of their previous assets.[62]:46

On 5 October 1939, Latvia was forced to accept a "mutual assistance" pact with the Soviet Union, granting the Soviets the right to station between 25,000 and 30,000 troops on Latvian territory.[65] State administrators were liquidated and replaced by Soviet cadres.[66] Elections were held with single pro-Soviet candidates listed for many positions. The resulting people's assembly immediately requested admission into the USSR, which the Soviet Union granted.[66] Latvia, then a puppet government, was headed by Augusts Kirhenšteins.[67] The Soviet Union incorporated Latvia on 5 August 1940, as The Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Soviets dealt harshly with their opponents – prior to Operation Barbarossa, in less than a year, at least 34,250 Latvians were deported or killed.[68] Most were deported to Siberia where deaths were estimated at 40 percent, officers of the Latvian army being shot on the spot.[62]:48

On 22 June 1941 German troops attacked Soviet forces in Operation Barbarossa.[69] There were some spontaneous uprisings by Latvians against the Red Army which helped the Germans. By 29 June Riga was reached and with Soviet troops killed, captured or retreating, Latvia was left under the control of German forces by early July[70].[62]:78–96 The occupation was followed immediately by SS Einsatzgruppen troops who were to act in accordance with the Nazi Generalplan Ost which required the population of Latvia to be cut by 50 percent.[62]:64[62]:56

Under German occupation, Latvia was administered as part of Reichskommissariat Ostland.[71] Latvian paramilitary and Auxiliary Police units established by the occupation authority participated in the Holocaust and other atrocities.[58] 30,000 Jews were shot in Latvia in the autumn of 1941.[62]:127 Another 30,000 Jews from the Riga ghetto were killed in the Rumbula Forest in November and December 1941, to reduce overpopulation in the ghetto and make room for more Jews being brought in from Germany and the West.[62]:128 There was a pause in fighting, apart from partisan activity, until after the siege of Leningrad ended in January 1944 and the Soviet troops advanced, entering Latvia in July and eventually capturing Riga on 13 October 1944.[62]:271

More than 200,000 Latvian citizens died during World War II, including approximately 75,000 Latvian Jews murdered during the Nazi occupation.[58] Latvian soldiers fought on both sides of the conflict, mainly on the German side, with 140,000 men in the Latvian Legion of the Waffen-SS,[72] The 308th Latvian Rifle Division was formed by the Red Army in 1944. On occasions, especially in 1944, opposing Latvian troops faced each other in battle.[62]:299

In the 23rd block of the Vorverker cemetery, a monument was erected after the Second World War for the people of Latvia, who had died in Lübeck from 1945 to 1950.

Soviet era (1940–1941, 1944–1991)

In 1944, when Soviet military advances reached Latvia, heavy fighting took place in Latvia between German and Soviet troops, which ended in another German defeat. In the course of the war, both occupying forces conscripted Latvians into their armies, in this way increasing the loss of the nation's "live resources". In 1944, part of the Latvian territory once more came under Soviet control. The Soviets immediately began to reinstate the Soviet system. After the German surrender, it became clear that Soviet forces were there to stay, and Latvian national partisans, soon joined by some who had collaborated with the Germans, began to fight against the new occupier.[73]

Anywhere from 120,000 to as many as 300,000 Latvians took refuge from the Soviet army by fleeing to Germany and Sweden.[74] Most sources count 200,000 to 250,000 refugees leaving Latvia, with perhaps as many as 80,000 to 100,000 of them recaptured by the Soviets or, during few months immediately after the end of war,[75] returned by the West.[76] The Soviets reoccupied the country in 1944–1945, and further deportations followed as the country was collectivised and Sovieticised.[58]

On 25 March 1949, 43,000 rural residents ("kulaks") and Latvian nationalists were deported to Siberia in a sweeping Operation Priboi in all three Baltic states, which was carefully planned and approved in Moscow already on 29 January 1949.[77] This operation had the desired effect of reducing the anti Soviet partisan activity.[62]:326 Between 136,000 and 190,000 Latvians, depending on the sources, were imprisoned or deported to Soviet concentration camps (the Gulag) in the post war years, from 1945 to 1952.[78] Some managed to escape arrest and joined the partisans.

In the post-war period, Latvia was made to adopt Soviet farming methods. Rural areas were forced into collectivization.[79] An extensive program to impose bilingualism was initiated in Latvia, limiting the use of Latvian language in official uses in favor of using Russian as the main language. All of the minority schools (Jewish, Polish, Belarusian, Estonian, Lithuanian) were closed down leaving only two media of instructions in the schools: Latvian and Russian.[80] An influx of new colonists, including laborers, administrators, military personnel and their dependents from Russia and other Soviet republics started. By 1959 about 400,000 Russian settlers arrived and the ethnic Latvian population had fallen to 62%.[81]

Since Latvia had maintained a well-developed infrastructure and educated specialists, Moscow decided to base some of the Soviet Union's most advanced manufacturing in Latvia. New industry was created in Latvia, including a major machinery factory RAF in Jelgava, electrotechnical factories in Riga, chemical factories in Daugavpils, Valmiera and Olaine—and some food and oil processing plants.[82] Latvia manufactured trains, ships, minibuses, mopeds, telephones, radios and hi-fi systems, electrical and diesel engines, textiles, furniture, clothing, bags and luggage, shoes, musical instruments, home appliances, watches, tools and equipment, aviation and agricultural equipment and long list of other goods. Latvia had its own film industry and musical records factory (LPs). However, there were not enough people to operate the newly built factories. To maintain and expand industrial production, skilled workers were migrating from all over the Soviet Union, decreasing the proportion of ethnic Latvians in the republic.[83] The population of Latvia reached its peak in 1990 at just under 2.7 million people.

In late 2018 the National Archives of Latvia released a full alphabetical index of some 10,000 people recruited as agents or informants by the Soviet KGB. 'The publication, which followed two decades of public debate and the passage of a special law, revealed the names, code names, birthplaces and other data on active and former KGB agents as of 1991, the year Latvia regained its independence from the Soviet Union.'[84]

Restoration of independence in 1991

In the second half of the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev started to introduce political and economic reforms in the Soviet Union that were called glasnost and perestroika. In the summer of 1987, the first large demonstrations were held in Riga at the Freedom Monument—a symbol of independence. In the summer of 1988, a national movement, coalescing in the Popular Front of Latvia, was opposed by the Interfront. The Latvian SSR, along with the other Baltic Republics was allowed greater autonomy, and in 1988, the old pre-war Flag of Latvia flew again, replacing the Soviet Latvian flag as the official flag in 1990.[85][86]

In 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a resolution on the Occupation of the Baltic states, in which it declared the occupation "not in accordance with law", and not the "will of the Soviet people". Pro-independence Popular Front of Latvia candidates gained a two-thirds majority in the Supreme Council in the March 1990 democratic elections. On 4 May 1990, the Supreme Council adopted the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia, and the Latvian SSR was renamed Republic of Latvia.[87]

However, the central power in Moscow continued to regard Latvia as a Soviet republic in 1990 and 1991. In January 1991, Soviet political and military forces tried unsuccessfully to overthrow the Republic of Latvia authorities by occupying the central publishing house in Riga and establishing a Committee of National Salvation to usurp governmental functions. During the transitional period, Moscow maintained many central Soviet state authorities in Latvia.[87]

In spite of this, 73% of all Latvian residents confirmed their strong support for independence on 3 March 1991, in a non-binding advisory referendum. The Popular Front of Latvia advocated that all permanent residents be eligible for Latvian citizenship, helping to sway many ethnic Russians to vote for independence. However, universal citizenship for all permanent residents was not adopted. Instead, citizenship was granted to persons who had been citizens of Latvia at the day of loss of independence at 1940 as well as their descendants. As a consequence, the majority of ethnic non-Latvians did not receive Latvian citizenship since neither they nor their parents had ever been citizens of Latvia, becoming non-citizens or citizens of other former Soviet republics. By 2011, more than half of non-citizens had taken naturalization exams and received Latvian citizenship. Still, today there are 290,660 non-citizens in Latvia, which represent 14.1% of the population. They have no citizenship of any country, and cannot vote in Latvia.[88]

The Republic of Latvia declared the end of the transitional period and restored full independence on 21 August 1991, in the aftermath of the failed Soviet coup attempt.[4]

.jpg.webp)

The Saeima, Latvia's parliament, was again elected in 1993. Russia ended its military presence by completing its troop withdrawal in 1994 and shutting down the Skrunda-1 radar station in 1998. The major goals of Latvia in the 1990s, to join NATO and the European Union, were achieved in 2004. The NATO Summit 2006 was held in Riga.[89]

Language and citizenship laws have been opposed by many Russophones. Citizenship was not automatically extended to former Soviet citizens who settled during the Soviet occupation, or to their offspring. Children born to non-nationals after the reestablishment of independence are automatically entitled to citizenship. Approximately 72% of Latvian citizens are Latvian, while 20% are Russian; less than 1% of non-citizens are Latvian, while 71% are Russian.[90] The government denationalized private property confiscated by the Soviets, returning it or compensating the owners for it, and privatized most state-owned industries, reintroducing the prewar currency. Albeit having experienced a difficult transition to a liberal economy and its re-orientation toward Western Europe, Latvia is one of the fastest growing economies in the European Union. In 2014, Riga was the European Capital of Culture, the euro was introduced as the currency of the country and a Latvian was named vice-president of the European Commission. In 2015 Latvia held the presidency of Council of the European Union. Big European events have been celebrated in Riga such as the Eurovision Song Contest 2003 and the European Film Awards 2014. On 1 July 2016, Latvia became a member of the OECD.[91]

Regional timeline

Affiliations of the areas that comprise modern Latvia in historical & regional context:

| Century | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Estonia | South Estonia | North Latvia | South Latvia | North Lithuania | South Lithuania | |

| 10th | Finnic tribes | Baltic tribes | ||||

| 11th | Ancient Estonia | |||||

| 12th | ||||||

| 13th | Danish Estonia | Livonian Order | Duchy of Lithuania | |||

| 14th | Grand Duchy of Lithuania | |||||

| 15th | ||||||

| 16th | Swedish Estonia | Duchy of Livonia | ||||

| 17th | Swedish Livonia | |||||

| 18th | Governorate of Estonia | Governorate of Livonia | Duchy of Courland and Semigallia | |||

| 19th | Courland Governorate | Government of Kaunas | Vilna Governorate | |||

| 20th | Republic of Estonia | Republic of Latvia | Republic of Lithuania | |||

| 21st | Republic of Estonia (EU) | Republic of Latvia (EU) | Republic of Lithuania (EU) | |||

Geography

Latvia lies in Northern Europe, on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea and northwestern part of the East European Craton (EEC), between latitudes 55° and 58° N (a small area is north of 58°), and longitudes 21° and 29° E (a small area is west of 21°). Latvia has a total area of 64,559 km2 (24,926 sq mi) of which 62,157 km2 (23,999 sq mi) land, 18,159 km2 (7,011 sq mi) agricultural land,[92] 34,964 km2 (13,500 sq mi) forest land[93] and 2,402 km2 (927 sq mi) inland water.[94]

The total length of Latvia's boundary is 1,866 km (1,159 mi). The total length of its land boundary is 1,368 km (850 mi), of which 343 km (213 mi) is shared with Estonia to the north, 276 km (171 mi) with the Russian Federation to the east, 161 km (100 mi) with Belarus to the southeast and 588 km (365 mi) with Lithuania to the south. The total length of its maritime boundary is 498 km (309 mi), which is shared with Estonia, Sweden and Lithuania. Extension from north to south is 210 km (130 mi) and from west to east 450 km (280 mi).[94]

Most of Latvia's territory is less than 100 m (330 ft) above sea level. Its largest lake, Lubāns, has an area of 80.7 km2 (31.2 sq mi), its deepest lake, Drīdzis, is 65.1 m (214 ft) deep. The longest river on Latvian territory is the Gauja, at 452 km (281 mi) in length. The longest river flowing through Latvian territory is the Daugava, which has a total length of 1,005 km (624 mi), of which 352 km (219 mi) is on Latvian territory. Latvia's highest point is Gaiziņkalns, 311.6 m (1,022 ft). The length of Latvia's Baltic coastline is 494 km (307 mi). An inlet of the Baltic Sea, the shallow Gulf of Riga is situated in the northwest of the country.[95]

Climate

Latvia has a temperate climate that has been described in various sources as either humid continental (Köppen Dfb) or oceanic/maritime (Köppen Cfb).[96][97][98]

Coastal regions, especially the western coast of the Courland Peninsula, possess a more maritime climate with cooler summers and milder winters, while eastern parts exhibit a more continental climate with warmer summers and harsher winters.[96]

Latvia has four pronounced seasons of near-equal length. Winter starts in mid-December and lasts until mid-March. Winters have average temperatures of −6 °C (21 °F) and are characterized by stable snow cover, bright sunshine, and short days. Severe spells of winter weather with cold winds, extreme temperatures of around −30 °C (−22 °F) and heavy snowfalls are common. Summer starts in June and lasts until August. Summers are usually warm and sunny, with cool evenings and nights. Summers have average temperatures of around 19 °C (66 °F), with extremes of 35 °C (95 °F). Spring and autumn bring fairly mild weather.[99]

| Weather record | Value | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest temperature | 37.8 °C (100 °F) | Ventspils | 4 August 2014 |

| Lowest temperature | −43.2 °C (−46 °F) | Daugavpils | 8 February 1956 |

| Last spring frost | – | large parts of territory | 24 June 1982 |

| First autumn frost | – | Cenas parish | 15 August 1975 |

| Highest yearly precipitation | 1,007 mm (39.6 in) | Priekuļi parish | 1928 |

| Lowest yearly precipitation | 384 mm (15.1 in) | Ainaži | 1939 |

| Highest daily precipitation | 160 mm (6.3 in) | Ventspils | 9 July 1973 |

| Highest monthly precipitation | 330 mm (13.0 in) | Nīca parish | August 1972 |

| Lowest monthly precipitation | 0 mm (0 in) | large parts of territory | May 1938 and May 1941 |

| Thickest snow cover | 126 cm (49.6 in) | Gaiziņkalns | March 1931 |

| Month with the most days with blizzards | 19 days | Liepāja | February 1956 |

| The most days with fog in a year | 143 days | Gaiziņkalns area | 1946 |

| Longest-lasting fog | 93 hours | Alūksne | 1958 |

| Highest atmospheric pressure | 31.5 inHg (1,066.7 mb) | Liepāja | January 1907 |

| Lowest atmospheric pressure | 27.5 inHg (931.3 mb) | Vidzeme Upland | 13 February 1962 |

| The most days with thunderstorms in a year | 52 days | Vidzeme Upland | 1954 |

| Strongest wind | 34 m/s, up to 48 m/s | not specified | 2 November 1969 |

2019 was the warmest year in the history of weather observation in Latvia with an average temperature +8.1°C higher.[101]

Environment

Most of the country is composed of fertile lowland plains and moderate hills. In a typical Latvian landscape, a mosaic of vast forests alternates with fields, farmsteads, and pastures. Arable land is spotted with birch groves and wooded clusters, which afford a habitat for numerous plants and animals. Latvia has hundreds of kilometres of undeveloped seashore—lined by pine forests, dunes, and continuous white sand beaches.[95][102]

Latvia has the 5th highest proportion of land covered by forests in the European Union, after Sweden, Finland, Estonia and Slovenia.[103] Forests account for 3,497,000 ha (8,640,000 acres) or 56% of the total land area.[93]

Latvia has over 12,500 rivers, which stretch for 38,000 km (24,000 mi). Major rivers include the Daugava River, Lielupe, Gauja, Venta, and Salaca, the largest spawning ground for salmon in the eastern Baltic states. There are 2,256 lakes that are bigger than 1 ha (2.5 acres), with a collective area of 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi). Mires occupy 9.9% of Latvia's territory. Of these, 42% are raised bogs; 49% are fens; and 9% are transitional mires. 70% percent of the mires are untouched by civilization, and they are a refuge for many rare species of plants and animals.[102]

Agricultural areas account for 1,815,900 ha (4,487,000 acres) or 29% of the total land area.[92] With the dismantling of collective farms, the area devoted to farming decreased dramatically – now farms are predominantly small. Approximately 200 farms, occupying 2,750 ha (6,800 acres), are engaged in ecologically pure farming (using no artificial fertilizers or pesticides).[102]

Latvia's national parks are Gauja National Park in Vidzeme (since 1973),[104] Ķemeri National Park in Zemgale (1997), Slītere National Park in Kurzeme (1999), and Rāzna National Park in Latgale (2007).[105]

Latvia has a long tradition of conservation. The first laws and regulations were promulgated in the 16th and 17th centuries.[102] There are 706 specially state-level protected natural areas in Latvia: four national parks, one biosphere reserve, 42 nature parks, nine areas of protected landscapes, 260 nature reserves, four strict nature reserves, 355 nature monuments, seven protected marine areas and 24 microreserves.[106] Nationally protected areas account for 12,790 km2 (4,940 sq mi) or around 20% of Latvia's total land area.[94] Latvia's Red Book (Endangered Species List of Latvia), which was established in 1977, contains 112 plant species and 119 animal species. Latvia has ratified the international Washington, Bern, and Ramsare conventions.[102]

The 2012 Environmental Performance Index ranks Latvia second, after Switzerland, based on the environmental performance of the country's policies.[107]

Access to biocapacity in Latvia is much higher than world average. In 2016, Latvia had 8.5 global hectares[108] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[109] In 2016 Latvia used 6.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use less biocapacity than Latvia contains. As a result, Latvia is running a biocapacity reserve.[108]

Biodiversity

Approximately 30,000 species of flora and fauna have been registered in Latvia.[111] Common species of wildlife in Latvia include deer, wild boar, moose, lynx, bear, fox, beaver and wolves.[112] Non-marine molluscs of Latvia include 159 species.

Species that are endangered in other European countries but common in Latvia include: black stork (Ciconia nigra), corncrake (Crex crex), lesser spotted eagle (Aquila pomarina), white-backed woodpecker (Picoides leucotos), Eurasian crane (Grus grus), Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), European wolf (Canis lupus) and European lynx (Felis lynx).[102]

Phytogeographically, Latvia is shared between the Central European and Northern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Latvia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests. 56 percent[93] of Latvia's territory is covered by forests, mostly Scots pine, birch, and Norway spruce. It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.09/10, ranking it 159th globally out of 172 countries.[113]

Several species of flora and fauna are considered national symbols. Oak (Quercus robur, Latvian: ozols), and linden (Tilia cordata, Latvian: liepa) are Latvia's national trees and the daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare, Latvian: pīpene) its national flower. The white wagtail (Motacilla alba, Latvian: baltā cielava) is Latvia's national bird. Its national insect is the two-spot ladybird (Adalia bipunctata, Latvian: divpunktu mārīte). Amber, fossilized tree resin, is one of Latvia's most important cultural symbols. In ancient times, amber found along the Baltic Sea coast was sought by Vikings as well as traders from Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire. This led to the development of the Amber Road.[114]

Several nature reserves protect unspoiled landscapes with a variety of large animals. At Pape Nature Reserve, where European bison, wild horses, and recreated aurochs have been reintroduced, there is now an almost complete Holocene megafauna also including moose, deer, and wolf.[115]

Administrative divisions

.png.webp)

Latvia is a unitary state, currently divided into 110 one-level municipalities (Latvian: novadi) and 9 republican cities (Latvian: republikas pilsētas) with their own city council and administration: Daugavpils, Jēkabpils, Jelgava, Jūrmala, Liepāja, Rēzekne, Riga, Valmiera, and Ventspils. There are four historical and cultural regions in Latvia – Courland, Latgale, Vidzeme, Zemgale, which are recognised in Constitution of Latvia. Selonia, a part of Zemgale, is sometimes considered culturally distinct region, but it is not part of any formal division. The borders of historical and cultural regions usually are not explicitly defined and in several sources may vary. In formal divisions, Riga region, which includes the capital and parts of other regions that have a strong relationship with the capital, is also often included in regional divisions; e.g., there are five planning regions of Latvia (Latvian: plānošanas reģioni), which were created in 2009 to promote balanced development of all regions. Under this division Riga region includes large parts of what traditionally is considered Vidzeme, Courland, and Zemgale. Statistical regions of Latvia, established in accordance with the EU Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, duplicate this division, but divides Riga region into two parts with the capital alone being a separate region. The largest city in Latvia is Riga, the second largest city is Daugavpils and the third largest city is Liepaja.

Politics

|

|

| Egils Levits President |

Arturs Krišjānis Kariņš Prime Minister |

The 100-seat unicameral Latvian parliament, the Saeima, is elected by direct popular vote every four years. The president is elected by the Saeima in a separate election, also held every four years. The president appoints a prime minister who, together with his cabinet, forms the executive branch of the government, which has to receive a confidence vote by the Saeima. This system also existed before World War II.[116] The most senior civil servants are the thirteen Secretaries of State.[117]

.jpg.webp)

Foreign relations

Latvia is a member of the United Nations, European Union, Council of Europe, NATO, OECD, OSCE, IMF, and WTO. It is also a member of the Council of the Baltic Sea States and Nordic Investment Bank. It was a member of the League of Nations (1921–1946). Latvia is part of the Schengen Area and joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2014.

Latvia has established diplomatic relations with 158 countries. It has 44 diplomatic and consular missions and maintains 34 embassies and 9 permanent representations abroad. There are 37 foreign embassies and 11 international organisations in Latvia's capital Riga. Latvia hosts one European Union institution, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC).[118]

Latvia's foreign policy priorities include co-operation in the Baltic Sea region, European integration, active involvement in international organisations, contribution to European and transatlantic security and defence structures, participation in international civilian and military peacekeeping operations, and development co-operation, particularly the strengthening of stability and democracy in the EU's Eastern Partnership countries.[119][120][121]

.jpg.webp)

Since the early 1990s, Latvia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with its neighbours Estonia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. The Baltic Council is the joint forum of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly (BA) and the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers (BCM).[122] Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB-8) is the joint co-operation of the governments of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, and Sweden.[123] Nordic-Baltic Six (NB-6), comprising Nordic-Baltic countries that are European Union member states, is a framework for meetings on EU-related issues. Interparliamentary co-operation between the Baltic Assembly and Nordic Council was signed in 1992 and since 2006 annual meetings are held as well as regular meetings on other levels.[123] Joint Nordic-Baltic co-operation initiatives include the education programme NordPlus[124] and mobility programmes for public administration,[125] business and industry[126] and culture.[127] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Riga.[128]

Latvia participates in the Northern Dimension and Baltic Sea Region Programme, European Union initiatives to foster cross-border co-operation in the Baltic Sea region and Northern Europe. The secretariat of the Northern Dimension Partnership on Culture (NDPC) will be located in Riga.[129] In 2013 Riga hosted the annual Northern Future Forum, a two-day informal meeting of the prime ministers of the Nordic-Baltic countries and the UK.[130] The Enhanced Partnership in Northern Europe or e-Pine is the U.S. Department of State diplomatic framework for co-operation with the Nordic-Baltic countries.[131]

Latvia hosted the 2006 NATO Summit and since then the annual Riga Conference has become a leading foreign and security policy forum in Northern Europe.[132] Latvia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2015.[133]

Human rights

According to the reports by Freedom House and the US Department of State, human rights in Latvia are generally respected by the government:[134][135] Latvia is ranked above-average among the world's sovereign states in democracy,[136] press freedom,[137] privacy[138] and human development.[139]

More than 56% of leading positions are held by women in Latvia, which ranks 1st in Europe; Latvia ranks 1st in the world in women's rights sharing the position with five other European countries according to World Bank.[140]

The country has a large ethnic Russian community, which was guaranteed basic rights under the constitution and international human rights laws ratified by the Latvian government.[134][141]

Approximately 206,000 non-citizens [142]– including stateless persons – have limited access to some political rights – only citizens are allowed to participate in parliamentary or municipal elections, although there are no limitations in regards to joining political parties or other political organizations.[143][144] In 2011, the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities "urged Latvia to allow non-citizens to vote in municipal elections."[145] Additionally, there have been reports of police abuse of detainees and arrestees, poor prison conditions and overcrowding, judicial corruption, incidents of violence against ethnic minorities, and societal violence and incidents of government discrimination against homosexuals.[134][146][147]

Military

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_667223.jpg.webp)

The National Armed Forces (Latvian: Nacionālie Bruņotie Spēki (NAF)) of Latvia consists of the Land Forces, Naval Forces, Air Force, National Guard, Special Tasks Unit, Military Police, NAF staff Battalion, Training and Doctrine Command, and Logistics Command. Latvia's defence concept is based upon the Swedish-Finnish model of a rapid response force composed of a mobilisation base and a small group of career professionals. From 1 January 2007, Latvia switched to a professional fully contract-based army.[148]

Latvia participates in international peacekeeping and security operations. Latvian armed forces have contributed to NATO and EU military operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1996–2009), Albania (1999), Kosovo (2000–2009), Macedonia (2003), Iraq (2005–2006), Afghanistan (since 2003), Somalia (since 2011) and Mali (since 2013).[149][150][151] Latvia also took part in the US-led Multi-National Force operation in Iraq (2003–2008)[152] and OSCE missions in Georgia, Kosovo and Macedonia.[153] Latvian armed forces contributed to a UK-led Battlegroup in 2013 and the Nordic Battlegroup in 2015 under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) of the European Union.[154] Latvia acts as the lead nation in the coordination of the Northern Distribution Network for transportation of non-lethal ISAF cargo by air and rail to Afghanistan.[155][156][157] It is part of the Nordic Transition Support Unit (NTSU), which renders joint force contributions in support of Afghan security structures ahead of the withdrawal of Nordic and Baltic ISAF forces in 2014.[158] Since 1996 more than 3600 military personnel have participated in international operations,[150] of whom 7 soldiers perished.[159] Per capita, Latvia is one of the largest contributors to international military operations.[160]

Latvian civilian experts have contributed to EU civilian missions: border assistance mission to Moldova and Ukraine (2005–2009), rule of law missions in Iraq (2006 and 2007) and Kosovo (since 2008), police mission in Afghanistan (since 2007) and monitoring mission in Georgia (since 2008).[149]

Since March 2004, when the Baltic states joined NATO, fighter jets of NATO members have been deployed on a rotational basis for the Baltic Air Policing mission at Šiauliai Airport in Lithuania to guard the Baltic airspace. Latvia participates in several NATO Centres of Excellence: Civil-Military Co-operation in the Netherlands, Cooperative Cyber Defence in Estonia and Energy Security in Lithuania. It plans to establish the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in Riga.[161]

Latvia co-operates with Estonia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives:

- Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) – infantry battalion for participation in international peace support operations, headquartered near Riga, Latvia;

- Baltic Naval Squadron (BALTRON) – naval force with mine countermeasures capabilities, headquartered near Tallinn, Estonia;

- Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) – air surveillance information system, headquartered near Kaunas, Lithuania;

- Joint military educational institutions: Baltic Defence College in Tartu, Estonia, Baltic Diving Training Centre in Liepāja, Latvia and Baltic Naval Communications Training Centre in Tallinn, Estonia.[162]

Future co-operation will include sharing of national infrastructures for training purposes and specialisation of training areas (BALTTRAIN) and collective formation of battalion-sized contingents for use in the NATO rapid-response force.[163] In January 2011, the Baltic states were invited to join NORDEFCO, the defence framework of the Nordic countries.[164] In November 2012, the three countries agreed to create a joint military staff in 2013.[165]

Economy

Latvia is a member of the World Trade Organization (1999) and the European Union (2004). On 1 January 2014, the euro became the country's currency, superseding the Lats. According to statistics in late 2013, 45% of the population supported the introduction of the euro, while 52% opposed it.[166] Following the introduction of the Euro, Eurobarometer surveys in January 2014 showed support for the euro to be around 53%, close to the European average.[167]

Since the year 2000, Latvia has had one of the highest (GDP) growth rates in Europe.[168] However, the chiefly consumption-driven growth in Latvia resulted in the collapse of Latvian GDP in late 2008 and early 2009, exacerbated by the global economic crisis, shortage of credit and huge money resources used for the bailout of Parex bank.[169] The Latvian economy fell 18% in the first three months of 2009, the biggest fall in the European Union.[170][171]

The economic crisis of 2009 proved earlier assumptions that the fast-growing economy was heading for implosion of the economic bubble, because it was driven mainly by growth of domestic consumption, financed by a serious increase of private debt, as well as a negative foreign trade balance. The prices of real estate, which were at some points growing by approximately 5% a month, were long perceived to be too high for the economy, which mainly produces low-value goods and raw materials.

Privatisation in Latvia is almost complete. Virtually all of the previously state-owned small and medium companies have been privatised, leaving only a small number of politically sensitive large state companies. The private sector accounted for nearly 68% of the country's GDP in 2000.

Foreign investment in Latvia is still modest compared with the levels in north-central Europe. A law expanding the scope for selling land, including to foreigners, was passed in 1997. Representing 10.2% of Latvia's total foreign direct investment, American companies invested $127 million in 1999. In the same year, the United States of America exported $58.2 million of goods and services to Latvia and imported $87.9 million. Eager to join Western economic institutions like the World Trade Organization, OECD, and the European Union, Latvia signed a Europe Agreement with the EU in 1995—with a 4-year transition period. Latvia and the United States have signed treaties on investment, trade, and intellectual property protection and avoidance of double taxation.[172][173]

In 2010 Latvia launched a Residence by Investment program (Golden Visa) in order to attract foreign investors and make local economy benefit from it. This program allows investors to get a Latvian residence permit by investing at least €250,000 in property or in an enterprise with at least 50 employees and an annual turnover of at least €10M.

Economic contraction and recovery (2008–12)

The Latvian economy entered a phase of fiscal contraction during the second half of 2008 after an extended period of credit-based speculation and unrealistic appreciation in real estate values. The national account deficit for 2007, for example, represented more than 22% of the GDP for the year while inflation was running at 10%.[174]

Latvia's unemployment rate rose sharply in this period from a low of 5.4% in November 2007 to over 22%.[175] In April 2010 Latvia had the highest unemployment rate in the EU, at 22.5%, ahead of Spain, which had 19.7%.[176]

Paul Krugman, the Nobel Laureate in economics for 2008, wrote in his New York Times Op-Ed column on 15 December 2008:

The most acute problems are on Europe's periphery, where many smaller economies are experiencing crises strongly reminiscent of past crises in Latin America and Asia: Latvia is the new Argentina[177]

However, by 2010, commentators[178][179] noted signs of stabilisation in the Latvian economy. Rating agency Standard & Poor's raised its outlook on Latvia's debt from negative to stable.[178] Latvia's current account, which had been in deficit by 27% in late 2006 was in surplus in February 2010.[178] Kenneth Orchard, senior analyst at Moody's Investors Service argued that:

The strengthening regional economy is supporting Latvian production and exports, while the sharp swing in the current account balance suggests that the country's 'internal devaluation' is working.[180]

The IMF concluded the First Post-Program Monitoring Discussions with the Republic of Latvia in July 2012 announcing that Latvia's economy has been recovering strongly since 2010, following the deep downturn in 2008–09. Real GDP growth of 5.5 percent in 2011 was underpinned by export growth and a recovery in domestic demand. The growth momentum has continued into 2012 and 2013 despite deteriorating external conditions, and the economy is expected to expand by 4.1 percent in 2014. The unemployment rate has receded from its peak of more than 20 percent in 2010 to around 9.3 percent in 2014.[181]

Infrastructure

The transport sector is around 14% of GDP. Transit between Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan as well as other Asian countries and the West is large.[182]

The four biggest ports of Latvia are located in Riga, Ventspils, Liepāja and Skulte. Most transit traffic uses these and half the cargo is crude oil and oil products.[182] Free port of Ventspils is one of the busiest ports in the Baltic states. Apart from road and railway connections, Ventspils is also linked to oil extraction fields and transportation routes of Russian Federation via system of two pipelines from Polotsk, Belarus.

Riga International Airport is the busiest airport in the Baltic states with 7.8 million passengers in 2019. It has direct flight to over 80 destinations in 30 countries. The only other airport handling regular commercial flights is Liepāja International Airport. airBaltic is the Latvian flag carrier airline and a low-cost carrier with hubs in all three Baltic States, but main base in Riga, Latvia.[183]

Latvian Railway's main network consists of 1,860 km of which 1,826 km is 1,520 mm Russian gauge railway of which 251 km are electrified, making it the longest railway network in the Baltic States. Latvia's railway network is currently incompatible with European standard gauge lines.[184] However, Rail Baltica railway, linking Helsinki-Tallinn-Riga-Kaunas-Warsaw is under construction and is set to be completed in 2026.[185]

National road network in Latvia totals 1675 km of main roads, 5473 km of regional roads and 13 064 km of local roads. Municipal roads in Latvia totals 30 439 km of roads and 8039 km of streets.[186] The best known roads are A1 (European route E67), connecting Warsaw and Tallinn, as well as European route E22, connecting Ventspils and Terehova. In 2017 there were a total of 803,546 licensed vehicles in Latvia.[187]

Latvia has three big hydroelectric power stations in Pļaviņu HES (825MW), Rīgas HES (402 MW) and Ķeguma HES-2 (192 MW). In the recent years a couple of dozen of wind farms as well as biogas or biomass power stations of different scale have been built in Latvia.

Latvia operates Inčukalns underground gas storage facility, one of the largest underground gas storage facilities in Europe and the only one in the Baltic states. Unique geological conditions at Inčukalns and other locations in Latvia are particularly suitable for underground gas storage.[188]

Demographics

The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2018 was estimated at 1.61 children born/woman, which is lower than the replacement rate of 2.1. In 2012, 45.0% of births were to unmarried women.[189] The life expectancy in 2013 was estimated at 73.19 years (68.13 years male, 78.53 years female).[174] As of 2015, Latvia is estimated to have the lowest male-to-female ratio in the world, at 0.85 males/female.[190] In 2017, there were 1,054,433 females and 895,683 males living in Latvian territory. Every year, more boys are born than girls. Until the age of 39, there are more males than females. From the age of 70, there are 2.3 times as many females than males.

Ethnic groups

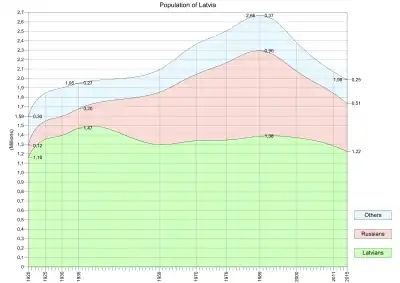

Latvia's population has been multiethnic for centuries, though the demographics shifted dramatically in the 20th century due to the World Wars, the emigration and removal of Baltic Germans, the Holocaust, and occupation by the Soviet Union. According to the Russian Empire Census of 1897, Latvians formed 68.3% of the total population of 1.93 million; Russians accounted for 12%, Jews for 7.4%, Germans for 6.2%, and Poles for 3.4%.[191]

As of March 2011, Latvians form about 62.1% of the population, while 26.9% are Russians, Belarusians 3.3%, Ukrainians 2.2%, Poles 2.2%, Lithuanians 1.2%, Jews 0.3%, Romani people 0.3%, Germans 0.1%, Estonians 0.1% and others 1.3%. 250 people identify as Livonians (Baltic Finnic people native to Latvia). There were 290,660 "non-citizens" living in Latvia or 14.1% of Latvian residents, mainly Russian settlers who arrived after the occupation of 1940 and their descendants.[192]

In some cities, e.g., Daugavpils and Rēzekne, ethnic Latvians constitute a minority of the total population. Despite the fact that the proportion of ethnic Latvians has been steadily increasing for more than a decade, ethnic Latvians also make up slightly less than a half of the population of the capital city of Latvia – Riga.[193]

The share of ethnic Latvians had fallen from 77% (1,467,035) in 1935 to 52% (1,387,757) in 1989.[194] In 2011, there were even fewer Latvians than in 1989, though their share of the population was larger – 1,285,136 (62.1% of the population).[195]

Language

The sole official language of Latvia is Latvian, which belongs to the Baltic language sub-group of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. Another notable language of Latvia is the nearly extinct Livonian language of the Finnic branch of the Uralic language family, which enjoys protection by law; Latgalian – as a dialect of Latvian is also protected by Latvian law but as a historical variation of the Latvian language. Russian, which was widely spoken during the Soviet period, is still the most widely used minority language by far (in 2011, 34% spoke it at home, including people who were not ethnically Russian).[196] While it is now required that all school students learn Latvian, schools also include English, German, French and Russian in their curricula. English is also widely accepted in Latvia in business and tourism. As of 2014 there were 109 schools for minorities that use Russian as the language of instruction (27% of all students) for 40% of subjects (the remaining 60% of subjects are taught in Latvian).

On 18 February 2012, Latvia held a constitutional referendum on whether to adopt Russian as a second official language.[197] According to the Central Election Commission, 74.8% voted against, 24.9% voted for and the voter turnout was 71.1%.[198]

Beginning in 2019, instruction in Russian language will be gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities in Latvia, as well as general instruction in Latvian public high schools,[199][200] except for subjects related to culture and history of the Russian minority, such as Russian language and literature classes.[201]

Religion

The largest religion in Latvia is Christianity (79%).[174][2] The largest groups as of 2011 were:

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia – 708,773[2]

- Roman Catholic – 500,000[2]

- Russian Orthodox – 370,000[2]

In the Eurobarometer Poll 2010, 38% of Latvian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", while 48% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 11% stated that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".

Lutheranism was more prominent before the Soviet occupation, when it was a majority religion of ~60% due to strong historical links with the Nordic countries and to the influence of the Hansa in particular and Germany in general. Since then, Lutheranism has declined to a slightly greater extent than Roman Catholicism in all three Baltic states. The Evangelical Lutheran Church, with an estimated 600,000 members in 1956, was affected most adversely. An internal document of 18 March 1987, near the end of communist rule, spoke of an active membership that had shrunk to only 25,000 in Latvia, but the faith has since experienced a revival.[202]

The country's Orthodox Christians belong to the Latvian Orthodox Church, a semi-autonomous body within the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2011, there were 416 religious Jews, 319 Muslims and 102 Hindus. Most of the Hindus are local converts from the work of the Hare Krishna movement; some are foreign workers from India.[2] As of 2004 there were more than 600 Latvian neopagans, Dievturi (The Godskeepers), whose religion is based on Latvian mythology.[203] About 21% of the total population is not affiliated with a specific religion.[2]

Education and science

The University of Latvia and Riga Technical University are two major universities in the country, both established on the basis of Riga Polytechnical Institute and located in Riga.[204] Other important universities, which were established on the base of State University of Latvia, include the Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies (established in 1939 on the basis of the Faculty of Agriculture) and Riga Stradiņš University (established in 1950 on the basis of the Faculty of Medicine). Both nowadays cover a variety of different fields. The University of Daugavpils is another significant centre of education.

Latvia closed 131 schools between 2006 and 2010, which is a 12.9% decline, and in the same period enrolment in educational institutions has fallen by over 54,000 people, a 10.3% decline.[205]

Latvian policy in science and technology has set out the long-term goal of transitioning from labor-consuming economy to knowledge-based economy.[206] By 2020 the government aims to spend 1.5% of GDP on research and development, with half of the investments coming from the private sector. Latvia plans to base the development of its scientific potential on existing scientific traditions, particularly in organic chemistry, medical chemistry, genetic engineering, physics, materials science and information technologies.[207] The greatest number of patents, both nationwide and abroad, are in medical chemistry.[208]

Health

The Latvian healthcare system is a universal programme, largely funded through government taxation.[209] It is among the lowest-ranked healthcare systems in Europe, due to excessive waiting times for treatment, insufficient access to the latest medicines, and other factors.[210] There were 59 hospitals in Latvia in 2009, down from 94 in 2007 and 121 in 2006.[211][212][213]

Culture

Traditional Latvian folklore, especially the dance of the folk songs, dates back well over a thousand years. More than 1.2 million texts and 30,000 melodies of folk songs have been identified.[214]

Between the 13th and 19th centuries, Baltic Germans, many of whom were originally of non-German ancestry but had been assimilated into German culture, formed the upper class. They developed distinct cultural heritage, characterised by both Latvian and German influences. It has survived in German Baltic families to this day, in spite of their dispersal to Germany, the United States, Canada and other countries in the early 20th century. However, most indigenous Latvians did not participate in this particular cultural life. Thus, the mostly peasant local pagan heritage was preserved, partly merging with Christian traditions. For example, one of the most popular celebrations is Jāņi, a pagan celebration of the summer solstice—which Latvians celebrate on the feast day of St. John the Baptist.

In the 19th century, Latvian nationalist movements emerged. They promoted Latvian culture and encouraged Latvians to take part in cultural activities. The 19th century and beginning of the 20th century is often regarded by Latvians as a classical era of Latvian culture. Posters show the influence of other European cultures, for example, works of artists such as the Baltic-German artist Bernhard Borchert and the French Raoul Dufy. With the onset of World War II, many Latvian artists and other members of the cultural elite fled the country yet continued to produce their work, largely for a Latvian émigré audience.[215]

The Latvian Song and Dance Festival is an important event in Latvian culture and social life. It has been held since 1873, normally every five years. Approximately 30,000 performers altogether participate in the event.[216] Folk songs and classical choir songs are sung, with emphasis on a cappella singing, though modern popular songs have recently been incorporated into the repertoire as well.[217]

After incorporation into the Soviet Union, Latvian artists and writers were forced to follow the socialist realism style of art. During the Soviet era, music became increasingly popular, with the most popular being songs from the 1980s. At this time, songs often made fun of the characteristics of Soviet life and were concerned about preserving Latvian identity. This aroused popular protests against the USSR and also gave rise to an increasing popularity of poetry. Since independence, theatre, scenography, choir music, and classical music have become the most notable branches of Latvian culture.[218]

During July 2014, Riga hosted the 8th World Choir Games as it played host to over 27,000 choristers representing over 450 choirs and over 70 countries. The festival is the biggest of its kind in the world and is held every two years in a different host city.[219]

Starting in 2019 Latvia hosts the inaugural Riga Jurmala Music Festival, a new festival in which world-famous orchestras and conductors perform across four weekends during the summer. The festival takes place at the Latvian National Opera, the Great Guild, and the Great and Small Halls of the Dzintari Concert Hall. This year features the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra and the Russian National Orchestra.[220]

Cuisine

Latvian cuisine typically consists of agricultural products, with meat featuring in most main meal dishes. Fish is commonly consumed due to Latvia's location on the Baltic Sea. Latvian cuisine has been influenced by the neighbouring countries. Common ingredients in Latvian recipes are found locally, such as potatoes, wheat, barley, cabbage, onions, eggs, and pork. Latvian food is generally quite fatty, and uses few spices.[221]

Grey peas and ham are generally considered as staple foods of Latvians. Sorrel soup (skābeņu zupa) is also consumed by Latvians.[222] Rupjmaize is a dark bread made from rye, considered the national staple.[223][224]

Sport

Ice hockey is usually considered the most popular sport in Latvia. Latvia has had many famous hockey stars like Helmuts Balderis, Artūrs Irbe, Kārlis Skrastiņš and Sandis Ozoliņš and more recently Zemgus Girgensons, whom the Latvian people have strongly supported in international and NHL play, expressed through the dedication of using the NHL's All Star Voting to bring Zemgus to number one in voting.[225] Dinamo Riga is the country's strongest hockey club, playing in the Kontinental Hockey League. The national tournament is the Latvian Hockey Higher League, held since 1931. The 2006 IIHF World Championship was held in Riga.

The second most popular sport is basketball. Latvia has a long basketball tradition, as the Latvian national basketball team won the first ever EuroBasket in 1935 and silver medals in 1939, after losing the final to Lithuania by one point. Latvia has had many European basketball stars like Jānis Krūmiņš, Maigonis Valdmanis, Valdis Muižnieks, Valdis Valters, Igors Miglinieks, as well as the first Latvian NBA player Gundars Vētra. Andris Biedriņš is one of the most well-known Latvian basketball players, who played in the NBA for the Golden State Warriors and the Utah Jazz. Current NBA players include Kristaps Porziņģis, who plays for the Dallas Mavericks, Dāvis Bertāns, who plays for the Washington Wizards, and Rodions Kurucs, who plays for the Brooklyn Nets. Former Latvian basketball club Rīgas ASK won the Euroleague tournament three times in a row before becoming defunct. Currently, VEF Rīga, which competes in EuroCup, is the strongest professional basketball club in Latvia. BK Ventspils, which participates in EuroChallenge, is the second strongest basketball club in Latvia, previously winning LBL eight times and BBL in 2013. Latvia was one of the EuroBasket 2015 hosts.

Other popular sports include football, floorball, tennis, volleyball, cycling, bobsleigh and skeleton. The Latvian national football team's only major FIFA tournament participation has been the 2004 UEFA European Championship.[226]

Latvia has participated successfully in both Winter and Summer Olympics. The most successful Olympic athlete in the history of independent Latvia has been Māris Štrombergs, who became a two-time Olympic champion in 2008 and 2012 at Men's BMX.[227]

In Boxing, Mairis Briedis is the first Latvian to win a boxing world title, having held the WBC cruiserweight title from 2017 to 2018, and the WBO cruiserweight title in 2019.

In 2017, Latvian tennis player Jeļena Ostapenko won the 2017 French Open Women's singles title being the first unseeded player to do so in the open era.

See also

References

- Social Statistics Department of Latvia. "Pastāvīgo iedzīvotāju etniskais sastāvs reģionos un republikas pilsētās gada sākumā". Social Statistics Department of Latvia. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Tieslietu ministrijā iesniegtie reliģisko organizāciju pārskati par darbību 2011. gadā" (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). Ojārs Kalniņš (ed.). The Latvian Saga (11th ed.). Riga: Atēna. p. 268. ISBN 9789984342917. OCLC 213385330.

- "History". Embassy of Finland, Riga. 9 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

Latvia declared independence on 21 August 1991...The decision to restore diplomatic relations took effect on 29 August 1991

- "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "Population number, its changes and density | Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia". www.csb.gov.lv.

- "Population Census 2011 – Key Indicators". Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. 2 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- "Latvia". IMF.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "The Constitution of the Republic of Latvia, Chapter 1 (Article 4)". The Parliament of the Republic of Latvia. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Official Language Law, Section 3 (Article 1)". The Parliament of the Republic of Latvia. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Official Language Law, Sections 4, 5 and 18 (Article 4)". Likumi.lv. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "Official Language Law, Section 3 (Articles 3 and 4)". The Parliament of the Republic of Latvia. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". United Nations. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- "Northern Europe - EU Vocabularies - Publications Office of the EU". op.europa.eu.

- "UN classifies Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia as Northern Europe - Jan. 09, 2017". KyivPost. 9 January 2017.

- "Latvia - Country Profile - Nations Online Project". www.nationsonline.org. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Latvia - Country Profile - Nations Online Project". www.nationsonline.org. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Latvia in Brief". Latvian Institute. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- "Latvia - Country Profile - Nations Online Project". www.nationsonline.org. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Weather information in Latvia". www.travelsignposts.com. 14 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "History of Latvia 1918-1940". [Latvia.eu]. 3 December 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Esther B. Fein. "UPHEAVAL IN THE EAST; Soviet Congress Condemns '39 Pact That Led to Annexation of Baltics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- On 21 August 1991, after the Soviet coup d'état attempt, the Supreme Council adopted a Constitutional law, "On statehood of the Republic of Latvia", declaring Article 5 of the Declaration to be invalid, thus ending the transitional period and restoring de facto independence.

- "Administrative divisions of Latvia". www.ambermarks.com. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Etniskais sastāvs un mazākumtautību kultūras identitātes veicināšana". Latvijas Republikas Ārlietu Ministrija. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- "IRG110. Population by citizenship and ethnicity at the beginning of the year". Statistikas datubāzes. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Socialinguistica: language and Religion". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "Advanced economies". IMF. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Latvia". World Bank. Archived from the original on 11 July 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Latvia – Country Profile: Human Development Indicators". hdr.undp.org. United Nations. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- "EU and euro". Bank of Latvia. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Latvia in Brief" (PDF). Latvian Institute. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- "Baltic Online". The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- "Data: 3000 BC to 1500 BC". The European Ethnohistory Database. The Ethnohistory Project. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- A History of Rome, M Cary and HH Scullard, p455-457, Macmillan Press, ISBN 0-333-27830-5

- Latvijas vēstures atlants, Jānis Turlajs, page 12, Karšu izdevniecība Jāņa sēta, ISBN 978-9984-07-614-0

- "Data: Latvia". Kingdoms of Northern Europe – Latvia. The History Files. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Latvian History, Lonely Planet". Lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- "The Crusaders". City Paper. 22 March 2006. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- "History of Latvia - Lonely Planet Travel Information". www.lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Johann Sehwers (1918). Die deutschen Lehnwörter im Lettischen: Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der hohen philosophischen Fakultät I der Universität Zürich (in German). Berichthaus.

- Ceaser, Ray A. (June 2001). "Duchy of Courland". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2 March 2003. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- O'Connor, Kevin (3 October 2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1 – via Google Books.

- Kasekamp, p. 47

- Rickard, J. "Truce of Altmark, 12 September 1629". www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 28 January 2021.