Selous Scouts

The Selous Scouts /səˈluː/ was a special forces regiment of the Rhodesian Army that operated from 1973 until the reconstitution of the country as Zimbabwe in 1980. Named after the British explorer Frederick Selous (1851–1917), its motto was pamwe chete—a Shona phrase meaning "all together", "together only" or "forward together".[2]

| Selous Scouts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 26 January 1973 – 18 April 1980 |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Special forces |

| Role | Asymmetric warfare |

| Size | 500 (estimated)[1] |

| Part of | Rhodesian Army |

| Conflict | Rhodesian Bush War |

| Commander | Ronald Francis Reid-Daly |

The charter of the Selous Scouts directed them to "the clandestine elimination of terrorism both within and without the country."[2]

Historical context

The period during which the Selous Scouts were most active was during the Rhodesian Bush War. This was a war backed by China and the Soviet Union—ZANLA–ZANU and ZIPRA–ZAPU—with the goal of ending minority rule in Rhodesia, a nation led by Prime Minister Ian Smith, and establishing an independent state under majority rule.

However, it was a small nation hegemonized by a few hundred thousand whites, principally farmers, and lacked access to the sea. As a land-locked nation, that had recently unilaterally declared its independence from Britain, Rhodesia was quickly isolated by the United Kingdom and the United States.

The Rhodesian military, comprising the Rhodesian Army and the Rhodesian Air Force, was considered rebellious by many foreign observers,[3] but the country's size—relative to the larger black-governed nations surrounding it, a lack of support from crucial Western suppliers, and aid provided by the Soviet Union and China to African freedom fighters—put Rhodesia in a precarious situation. To deal with the rising power of the African Nationalist Militia Fighters, the Rhodesian government strengthened diplomatic and economic ties with South Africa, as well as with Portugal, which controlled the neighbouring territory of Mozambique until 1975.

It concurrently began strengthening its paramilitary and counter-insurgency forces such as the British South Africa Police, the Rhodesian Light Infantry, the Rhodesian Special Air Service, and the Rhodesian African Rifles. Ultimately, these efforts led to the creation of its counter-insurgency unit, the Selous Scouts.

Created under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Reid-Daly, it was organized as a mixed-race unit, consisting of recruits of both African and European descent, and whose primary mission was operating deep in insurgent-controlled territory and waging war on the hostiles' rear through irregular warfare including the use of pseudo-terrorism as a means of infiltrating the enemy. This concept of unit was very similar to the Portuguese Flechas, operating in the nearby territories of Angola and Mozambique since the late 1960s. The Scouts had many black Rhodesians in their ranks who were from 50 to 80% of its ranks, including the first African commissioned officers in the Rhodesian Army.[4]

Tactics

The Selous Scouts employed asymmetric warfare against their enemy, actions that ranged from the bombing of private houses, abductions, M18 Claymore mine attacks against military targets, sabotage of bridges and railways (including steam engines), assassinations, intimidation, blackmail and extortion, to the use of car bombs in the attempted assassination of Joshua Nkomo.[5]

Intelligence gathering

Many times, due to their intelligence collecting, the HUMINT side of the Scouts was more up to date than the guerrillas.[6] The job of intelligence—and the task of the Scouts as well as the special branches in general—was to find out the identity of the insurgents, their plans, their training locations, the parties involved in training them, the source and location of their supply routes, their sympathizers, and any other relevant information.[7] The pseudo-operators gained entrance into the areas controlled by ZANLA–ZIPRA through memorization of dead drops, presenting the appropriate letter at the necessary time, and by use of the information given by their intelligence. Compartmentalization was key, and the need-to-know basis was strictly enforced.[8]

In order to gain entrance into the surrounding African countries they were required to use their callsigns and tribal spies for ZANLA–ZIPRA, in order to process and compile names so as to enable them to enter a country covertly or as "illegals".[9] While on a mission to assassinate Nkomo they had to observe operational security. This consisted of using code words to tell a handler when one was out of money or to warn the agent if the authorities were aware of his activities in Zambia. This message would tell the scout whether he had to leave Zambia by the traditional route of using buses or cars or if he had to leave Zambia through the bush.[10]

Turning of guerrillas

Part of the problem in the early days of the Selous Scouts and Rhodesia, was that the security forces and the guerrillas had clearly defined roles.[11] In the first days of the Scouts in 1973–1974, the objective of the government and the military was to kill or incarcerate as many guerrillas as they could, which was deemed good for public morale.[12]

There was no previously accepted convention that one could absorb "real" or "tamed" guerrillas within the ranks of an elite pseudo-guerrilla group, so as to be able to extract intelligence, be aware of how they dressed, behaved and thought, used callsigns or observed operational security. The thinking of the leadership of the Scouts was that if a guerrilla—for example a regional or detachment officer of ZIPRA–ZANLA—were to be captured and turned, then the existing network already in place could be used in order to boost their numbers of kills as well as gather further intelligence.[13]

When the Scouts captured a guerrilla in the field they had to make a decision between three options: execute him immediately; hand him over to others in a special division for trial and certain hanging under the Law and Order (Maintenance) Act; or try to absorb him into the Scouts. If the guerrilla were injured in a skirmish, the first thing would be to make sure that no one knew of his existence: neither the locals in the area nor anyone at the security base. While still wounded the guerrilla would be brought into the Scouts' fort and given the best medical attention. With the realisation that his life was being saved, a feeling of gratitude would normally follow.[14]

The next step was to send a former guerrilla or "tame terr" to visit him in the hospital. A conversation would be initiated and eventually steered round to a reminder of hardships in the bush, and of the probability of a trial and hanging under the Law and Order (Maintenance) Act without his compliance.[15] He would next be examined by the Scouts only, in order to ensure loyalty; if passed, he would be given a lump sum of money as well as a regular paying job for joining. Additionally, and where possible, the guerrilla's family would be moved into protection where they would receive free rations, housing, education, and medical care.[14]

In most cases the guerrilla chose to side with the security forces. The Scouts had to make a final, difficult decision on whether to allow the turned guerrilla into their group or not. This decision had largely to do with their gut feeling of how the guerrilla presented himself: was he trustworthy or was he just biding his time? A fail-safe to test his loyalty was to hand him his weapon back, without prior knowledge that his ammunition had been rendered harmless. This was only temporary though, as the "tame terr" would soon become an integral member of the unit.[16]

Other tactics

The operators also took measures to weaken popular support for the guerrillas; in one case, for example, a group of operators pretending to be guerrillas accused eight of the most enthusiastic guerrilla supporters in the Madziwa region of being police informers and beat them up before leaving.[17] Detractors cited events like this as the difference between anti-terrorism and counter-terrorism.

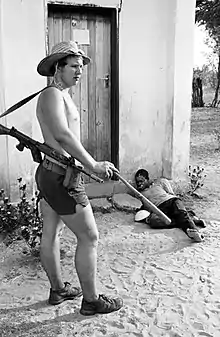

The Scouts' unconventional tactics were the subject of photographs by J. Ross Baughman that won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography in 1978. He provides one of the only detailed eyewitness accounts by an outsider of the Scouts in operation. Describing one technique, he wrote: "They force them to line up in push-up stance. They're holding that position for 45 minutes in the sun, many of them starting to shake violently. Eventually, the first guy fell. They took him around the back of the building, knocked him out and fired a shot into the air. They continued bring men to the back of the building. The poor guy on the end started crying and going crazy and he finally broke and started talking. As it turns out, what he was saying wasn't true, but the scouts were willing to use it as a lead. It had all the feeling of an eventual massacre. I was afraid that I might see entire villages murdered."

Baughman had to smuggle the film out of the country. Some people doubted the authenticity of the photos at first, but they were later accepted and Baughman said that the skeptics apologized to him.[18] The camouflage used by reserve members of this unit as pseudo-forces were captured Warsaw Pact clothing originating from various countries and specified for certain operations.

The regiment achieved many of its objectives; its members were acclaimed trackers, and the unit was responsible for 68% of all guerrilla deaths—mainly through the Fireforce operations—within the borders of Rhodesia.[19] However, its commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Reid-Daly, had a poor relationship with many of the Rhodesian Army commanders;[20] in addition, from 1978, there were persistent rumours that soldiers in the regiment had been implicated in ivory poaching in the Gonarezhou National Park and that an ivory processing "factory" existed at Andre Rabie Barracks near Inkomo Garrison.[20] The friction between the army command and Reid-Daly peaked on 29 January 1979, when a bugging device was found in Reid-Daly's office. This compromised ongoing Selous Scout operations, and therefore it became necessary to call them off.[21]

The intelligence collection function of the Scouts was overseen by an embedded element of the British South Africa Police Special Branch (SB), commanded by Chief Superintendent Michael McGuinness.[22] The SB liaison team conducted interrogations of captured guerrillas, reviewed captured documents, and collated and disseminated intelligence.[23] The SB team also oversaw the production and insertion of poisoned clothing, food, beverages, and medicines into the guerrilla supply chain.[24] The use of contaminated supplies resulted in the reported deaths of over 800 guerrillas, and the likely death toll probably reached well over 1,000.[24]

The Scouts numbered only about 500. When they would "turn" guerrillas they would be known as "tame terr". This figure would rise to 1,000 "tame" terr if one counted the active and inactive members.[1] According to a Combined Operations statement, they brought about 68% of the nationalist guerrilla fatalities between 1973 and 1980.[25] while losing fewer than 40 Scouts in the process.[26]

Composition

The regiment was proposed by members of the British South Africa Police special branch, and many of its earliest recruits were policemen. The Rhodesian Light Infantry was also a driving force behind the Selous Scouts.

The Scouts differed from C Squadron 22 (Rhodesian) SAS, in that it was formed specifically to take part in tracking and infiltration operations, where soldiers would pretend to be guerrillas—or pseudo-operators. These tactics were used very successfully in the Mau Mau Uprising. In fact, the regiment also recruited from enemy forces; captured guerrillas were offered a choice between imprisonment, trial and possibly execution or the ability to join the Scouts.[27]

This concept was initially highly controversial within the Rhodesian government; the idea of "turning" captured guerrillas instead of punishing them was unpalatable to some.[28] However, supporters of "turning", who succeeded in implementing their plans, portrayed these operations as an aspect of counter-insurgency similar to the law enforcement use of informants and 'sting' methods to penetrate and disrupt criminal and subversive organizations.

In order to keep knowledge of their existence as restricted as possible, "turned" guerrillas were paid from Special Branch funds which were not accountable to government auditors,[29] and volunteers for the unit were not told of its actual function until they actually joined it;[30] in some cases, where captured guerrillas had already entered the judicial system, the Scouts would fake their escapes without informing the Criminal Investigation Department.[31]

To prevent the regular army or police from firing at the regiment while it was operating, authorities would declare "frozen areas", where all Army and Police units were ordered to temporarily cease all operations in, and withdraw from, without being told the actual rationale.[32] Many commanders felt that the initiation of "frozen areas" ceded control to the enemy and reduced the initiative of the security forces.

Notable features

People of many different races and countries of origin were employed in the Selous Scouts, including Portuguese, British, South African, American, and various African countries.[33]

The regimental badge signifies the osprey, a fish-eating bird of prey found in small numbers in many parts of the world.

Selection and training

The Selous Scouts were a combat reconnaissance force, with the mission of infiltrating Rhodesia's tribal population and guerrilla networks, pinpointing rebel groups and relaying vital information back to the conventional forces earmarked to carry out the actual attacks. Members of the regiment were trained to operate in small under-cover, clandestine teams capable of working independently in the bush for a number of weeks and of passing themselves off as rebels. The Scouts were a volunteer force. On one occasion 14 out of 126 candidates passed the selection process.

As Reid-Daly stated: "a special force soldier has to be a certain very special type of man. In his profile it is necessary to look for intelligence, fortitude and guts potential, loyalty, dedication, a deep sense of professionalism, maturity—the ideal age being 24 to 32 years—responsibility and self discipline ..."[21] The person that the Scouts were looking for was a mix between the soldier who can work in a unit and a loner who can think and act on his feet.[34]

Selection was rigorous, and even tougher than the Rhodesian Special Air Service course. When volunteers arrived at Wafa Wafa, the Scouts' training camp, on the shores of Lake Kariba they were given a taste of the hardships they would have to endure. On reaching the base—which was a 25 kilometres (16 mi) run away from the drop-off point—they saw only a few straw huts and the blackened embers of a dying fire. There was no food issued. The objective of the training at this point was to reduce the number of potential recruits by starving, exhausting and antagonising them. This was successful, with 40 or 50 men out of 60 usually dropping out within the first two days of training.

The selection course had a total duration of 17 days. From dawn to 7 a.m., recruits were put through a strength-sapping fitness programme. After they had completed this, they trained in basic combat skills. They were also required to traverse a difficult assault course several times during the training programme. The course was designed to overcome their fear of heights. When darkness fell, they began night training. In the first five days of the course, no food was issued, while for the rest of the period only rotten animals were allowed. At the end of training, they had to undertake an endurance march of 100 kilometres (62 mi). Each volunteer was laden with 30 kilograms (66 lb) of rocks in his packs. The rocks were painted red, to ensure that they could not be removed and replaced at the end.[21]

The final stage of the march was a speed march, and had to be completed in two-and-a-half hours. For those who survived these days there was a week of leave; they were then taken to a special camp for the "dark phase" of their training. At this camp, they learned to act and talk like the enemy. The base was built and set out as a rebel camp, and the instructors taught them akin to enemy groups. In this phase recruits were taught to break with habits such as shaving, rising at regular times, smoking and drinking and to adopt a guerrilla lifestyle. The recruits were in the field on patrol with the Scouts only a week after the completion of their training.[21]

Notable operations

Operation Long John was launched on 25 June 1976, against two guerilla bases located in Mozambique.[35] While on Operation Prawn inside of Mozambique, the objective of which was sabotaging the railways of FRELIMO, they had difficulties at first setting the charges. So they decided to kill a guerrilla and dress him up as a Rhodesian security force member and then throw bogus documents everywhere. The FRELIMO patrol took the bait and left the scene, and then the charges were placed and detonated and the operation was a success.[36]

Apart from their internal security of Rhodesia, some notable operations outside of Rhodesia's borders struck fear into the enemy. A particular mission took place was first thought to be a flop in Francistown, Botswana. Numerous suitcase bombs were planted by the Selous Scouts in order to liquidate ZIPRA command; the ones that did go off, went off too late and one failed to explode outside of a house. The Botswana authorities thought that ZIPRA's explosion was due to their improper handling and care of the bombs. As a result, Botswana banned the importation of suitcase bombs within the country supplied by the Russians to ZIPRA, which undoubtedly saved the lives of Rhodesians.[37]

Operation Eland was a cross border operation that took place in Mozambique in August 1976. It involved ten trucks and four armoured cars disguised as FRELIMO vehicles with 84 Scouts. They first cut the telephone lines to the town and drove on to the guerrilla base. Eighty-four scouts opened fire on the guerrillas at close range, killing 1,028 people in the camp. The camp was registered as a refugee camp by the United Nations, but this was later found to be false. Even according to Reid-Daly, most of those killed were unarmed guerrillas standing in formation for a parade. The camp hospital was also set ablaze by the rounds fired by the Scouts, killing all patients.[38]

The scouts did not sustain any fatalities. Captured ZANLA documents revealed that most of those killed in the raid were either trained guerrillas or were undergoing guerrilla instruction.[39][40] As a result of their pseudo-operations, ZANLA were getting into firefights with other members of their guerrilla organization who assumed that they were the Scouts. This invoked fear within the enemy and led to their command and communication structure being disrupted. Additionally, this meant that groups entering Rhodesia for the first time found difficulty linking up with the other members of the group; this led to a demoralisation effect since each guerrilla had to be extremely cautious about whomever he met. [41]

By 1974, the Scouts had captured or killed 100 guerrillas.[42] By the end of 1976, they killed 1,257 guerrillas that year alone. The other security forces of Rhodesia combined had killed only 400.[43]

Dissolution

Following the dissolution of the regiment in 1980, many of its soldiers travelled south to join the South African Defence Force, where they joined 5 Reconnaissance Commando. Those that remained formed 4th Bn(HU)R.A.R. which was placed on "immediate standby" for most of its short service. The battalion covered the areas to the north of Andre Rabie Barracks, as far as Miami–Mangula in the east and as far as Kariba in the north. The unit existed from 23 April to 30 September 1980, when it changed its name for the final time and became as it is today, 1st Zimbabwe Parachute Battalion/Group.

Namesake

The name Selous Scouts was also given to the short-lived Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment (Selous Scouts), a unit in the Army of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland between about 1960 and 1963 that drove Ferret armoured cars.

Footnotes

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 98.

- Melson 2005, pp. 57–82.

- "The World: The Military: A Mission Impossible". Time. New York. 13 June 1977. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 105.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 223–224, 290, 302, 625.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 229.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 30.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 623.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 445.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 618, 628.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 50.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 58.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 217.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 105–107.

- Stapleton 2011, p. 204.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 105–106.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 33.

- Baughman, J. R. "J. Ross Baughman – Rhodesia". Iconic Photos. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Radford, M. P., Service Before Self, 1994

- Godwin & Hancock 1995, pp. 241–242.

- Stiff 1981.

- Ron Reid-Daly as told to Peter Stiff. Selous Scouts: Top Secret War. Alberton, South Africa: Galago Publishing, 1982

- Ron Red-Daly as told to Peter Stiff. Selous Scouts: Top Secret War. Alberton, South Africa: Galago Publishing, 1982.

- Glenn Cross. Dirty War: Rhodesia and Chemical Biological Warfare, 1975–1980. Solihill: Helion & Company, 2017

- McNab, Chris, Modern Military Uniforms, Chartwell Books, Inc., 2000, p. 158.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 15.

- Reid-Daly 2001, pp. 189–190.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 26.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 31.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 116.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 60.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 41.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 448.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 240–241.

- Cilliers 1985, p. 177.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 419.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 444.

- Cline (2005), quoting Reid-Daly, Pamwe Chete: The Legend of the Selous Scouts, Weltevreden Park, South Africa: Covos-Day Books, 1999, p. 10 (republished by Covos Day, 2001, ISBN 978-1-919874-33-3)

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 397–406.

- Moorcraft & McLaughlin 2010, p. 207.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, pp. 218–19.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 192.

- Stiff & Reid-Daly 1982, p. 402.

References

- Cilliers, J. K. (1985). Counter-insurgency in Rhodesia. Routledge. p. 177. ISBN 0709934122.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cross, G. (2017). Dirty War: Rhodesia and Chemical Biological Warfare, 1975–1980. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-911512-12-7.

- Godwin, P.; Hancock, I. (1995). Rhodesians Never Die – The Impact of War and Political Change on White Rhodesia. Harare, Zimbabwe: Baobab Books. ISBN 0-908311-82-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Melson, C. D. (2005). "Top Secret War: Rhodesian Special Operations". Small Wars and Insurgencies (No. 1 ed.). 16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moorcraft, P. L.; McLaughlin, P. (2010). The Rhodesian War: A Military History. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811707251.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poole, H. John (2006). "10: Selous Scout Infiltration". Terrorist Trail: Backtracking the Terrorist Fighter. Prosperity Press. ISBN 978-0963869593.

- Reid-Daly, R. F. (2001). Pamwe Chete – The Legend of the Selous Scouts. Weltevreden Park, South Africa: Covos Day Books. ISBN 1-919874-33-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stapleton, T. (2011). African Police and Soldiers in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1923–80. University Rochester Press. ISBN 1580463800.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiff, P.; Reid-Daly, R. (1982). Selous Scouts: Top Secret War. Alberton (South Africa): Galago.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiff, P. (April 1981). "Scouting for Danger". Soldier of Fortune.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)