Sefer HaTemunah

Sefer HaTemunah (Hebrew: ספר התמונה) (lit. "Book of the Figure", i.e. shape of the Hebrew letters) is a 13–14th century kabbalistic text. It is quoted in many Halakhic sources.

| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

Origins

Sefer HaTemunah was probably written anonymously in the 13th or 14th century, but it is pseudepigraphly attributed to Nehunya ben HaKanah and Rabbi Ishmael, tannaim of the 1st and 2nd centuries.[1][2] According to Hebrew Manuscripts in the Vatican Library Catalog, the work was composed in the 1270s. The first extant edition was published in the city of Korets in Poland in 1784.[3] Aegidius of Viterbo, a 15th-century cardinal, was influenced by Sefer HaTemunah, as can be seen in his writings Shekhinah and On the Hebrew Letters.[4]

Concepts

Sabbatical cycles and the age of the universe

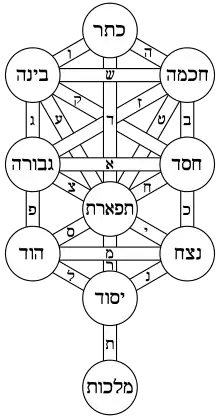

One of the main concepts in Sefer HaTemunah is that of the connection of the Sabbatical year (Hebrew: Shmita) with sephirot and the creation of more than one world. The author of Sefer HaTemunah believed that worlds are created and destroyed, supporting this theory with a quote from the Midrash, "God created universes and destroys them."[1] The Talmud (Sanhedrin 97a) states that "Six thousand years shall the world exist, and one [thousand, the seventh], it shall be desolate".[5] Sefer HaTemunah asserts that this 7000-year cycle is equivalent to one Sabbatical cycle. Because there are seven such cycles per Jubilee, the author concludes that the world will exist for 49,000 years.[1]

According to some sources, the author of Sefer HaTemunah believed that the world was currently in the second Sabbatical cycle, corresponding to Gevurah (Severity), which occurs between the cycles Chesed (Kindness) and Tiferet (Adornment).[6] Sefer HaTemunah offers a description of the final Shmita, Malkuth (Kingdom), as "distinctly utopian" in character. This may explain why the book was widely embraced by Kabbalists.[7]

According to Kaplan[8] the Sabbatical cycles in Sefer HaTemunah can be used as a basis for calculating the age of the universe. While Sefer HaTemunah sees the world as existing in the second cycle, others[9] say it is in the seventh cycle.[1] If so, Adam was created when the universe was 42,000 years old, and six worlds were created and destroyed before the creation of Adam.[1] This thesis was laid out by Rabbi Isaac ben Samuel of Acre, a 13th-century Kabbalist, who said that when calculating the age of the universe, one must use divine years rather than physical years.

I, the insignificant Yitzchak of Akko, have seen fit to write a great mystery that should be kept very well hidden. One of God's days is a thousand years, as it says, "For a thousand years are in Your eyes as a fleeting yesterday." Since one of our years is 365 ¼ days, a year on High is 365,250 our years.[10]

Rabbi Yitzchak of Akko then goes on to explain a value of 49,000 years, but does not proceed with the multiplication, nor the reduction of 49,000 to 42,000, which is Kaplan's own interpretation. Kaplan calculates the age of the universe to be 15,340,500,000 years old.[1][11] His reasoning was as follows: as the Midrash states, "A thousand years in your sight are but as yesterday" (Psalm 90:4); a physical year contains 365 ¼ days, which, if multiplied by 1000 would give the length of a divine year as 365,250 physical years; if we are living in the last, 7th Sabbatical cycle, that would mean that the creation as it described in the Bible happened 42,000 divine years ago; to convert this figure to physical years it should be multiplied by 365,250; this gives the result 15,340,500,000 years.[1]

In 1993, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan wrote that the Big Bang occurred "approximately 15 billion years ago", calling this "the same conclusion" as the 13th century kabbalists.[1] According to a 2015 estimate by ESA's Planck project, the age of the universe is 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years.[12] Kaplan also relates to Sefer HaTemunah the idea that Torah teachings are compatible with other areas of modern science. According to Kaplan, Orthodox Jews often challenge the findings of paleontology and geology as conflicting with Torah concepts. But in an "extremely controversial" essay, Israel Lipschitz drew on the writings of Abraham ibn Ezra, Nahmanides, and Bahya ibn Paquda to argue the opposite conclusion: "See how the teachings of our Torah have been vindicated by modern discoveries." Lipschitz wrote that fossils of mammoths and dinosaurs represent previous Sabbatical cycles in which humans and other beings lived in universes before Adam, and that the Himalayas were formed in a great upheaval, one of the upheavals mentioned in Sefer HaTemunah.[1]

Missing letter

Hebrew letters are invested with special meaning in Judaism in general, and in Kabbalah even more so. The creative power of letters is particularly evident in Sefer Yetzirah (Hebrew: book of creation), a mystical text that tells a story of the creation which is based on the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, a story which diverges greatly from that in the Book of Genesis. The creative power of letters is also explored in the Talmud and Zohar.[13][14]

In Kabbalah, every Shmita corresponds to individual emotional sephirot (the lower seven sephirot from Chessed to Malchut, named middot). 13th-century scholar Nahmanides asserted that the Torah could be read differently through different pronunciation and word divisions. Building on this idea, the author of Sefer HaTemunah asserted that the Torah is read in a different way during each Shmita. The author further stated that one Hebrew letter is missing altogether from the Torah, and will be revealed only when the world moves to the next sephira.[15]

According to Lawrence Kushner, author of The Book of Letters: A Mystical Alef-Bait, Sefer HaTemunah teaches that "every defect in our present universe is mysteriously connected with this unimaginable consonant", and that as soon as the missing letter is given to us, our Universe will be filled with undreamed of new words, the words that will turn repression into loving.[16]

Kushner states that the letter Shin (ש) is of special interest. The letter shin that appears on the small leather cube that holds the tefillin has four prongs rather than the standard three. Some scholars say that this is the missing letter. According to these scholars, the coming revelation of the name and pronunciation of this letter will be what repairs the universe.[16]

Interpretation of Cosmic Shmitot in later Kabbalah

View of Luria

From the Medieval flourishing of Kabbalah onwards, attempts were made to systemise its diverse teachings, especially commentaries on the elusive imagery of the Zohar. Sixteenth century Safed saw the realisation of this aim in the two normative, comprehensive versions of Kabbalistic theosophy: the quasi-rational linear scheme of Moshe Cordovero, followed by the supra-rational dynamic scheme of Isaac Luria that replaced it. Their view of the earlier doctrine from Sefer HaTemunah, of previous Cosmic Shmitah cycles before ours, was that previous cycles refer to spiritual processes, not actual creations; our universe being the first physical creation.[17]

References

- Aryeh Kaplan, Yaakov Elman, Israel ben Gedaliah Lipschutz (January 1993). Immortality, resurrection, and the age of the universe: a kabbalistic view. Ktav Publishing House. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978-0-88125-345-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Isibiel Myrna Cohen. "SEFER HA-TEMUNAH". Christie's.

- Benjamin Richler (2008). "Hebrew Manuscripts in the Vatican Library Catalogue" (PDF). CITTA` DEL VATICANO BIBLIOTECA APOSTOLICA VATICANO. p. 160.

- Gershom Gerhard Scholem (1998). Kabbalah. Buccaneer Books; 1st Edition. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-88029-205-4.

- Freedman, H., Isidore Epstein (ed.), Tractate Sanhedrin, Hebrew-English edition of the Babylonian Talmud, 19, London: Soncino Press, Folio 97a, ISBN 0-900689-88-9. Republished as Babylonian Talmud: Sanhedrin 97, halakhah.com, retrieved 24 July 2010

- Frank Edward Manuel; Fritzie Prigohzy Manuel (October 31, 1979). Utopian thought in the Western World. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-674-93185-5.

- Leonora Leet (March 2003). The Kabbalah of the Soul: The Transformative Psychology and Practices of Jewish Mysticism. Inner Traditions; First Edition, First Printing edition. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-89281-957-7.

- Kaplan, A. (1993), Immortality, Resurrection and the Age of the Universe

- Sefer Livnat HaSapir quoted in A. Kaplan, "The Age of the Universe"

- Natan Slifkin (July 18, 2006). The Challenge of Creation: Judaism's Encounter with Science, Cosmology, and Evolution. Yashar Books; Assumed First edition. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-933143-15-6.

- Elizabeth Clare Prophet; Patricia R. Spadaro; Murray L. Steinman (September 1, 1997). Kabbalah: Key To Your Inner Power (Mystical Paths of the World's Religions). Summit University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-922729-35-7.

- Planck Collaboration (2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters (See Table 4 on page 31 of pfd)". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594: A13. arXiv:1502.01589. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. S2CID 119262962.

- Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Berachot 55c

- Zohar 1:3; 2:152

- Mosheh Ḥalamish (1999). An introduction to the Kabbalah. State University of New York. p. 222. ISBN 9780791440117.

- Lawrence Kushner (1990). The Book of Letters: A Mystical Alef-Bait. Jewish Lights Publishing; 2nd edition. p. 13,14. ISBN 978-1-879045-00-2.

- The Shemitot and the age of the Universe, 3 part video class on "Sefer HaTemunah" by Yitzchak Ginsburgh on inner.org