Lurianic Kabbalah

Lurianic Kabbalah is a school of kabbalah named after the Jewish rabbi who developed it, Isaac Luria (1534–1572; also known as the "ARI'zal", "Ha'ARI" or "Ha'ARI Hakadosh"). Lurianic Kabbalah gave a seminal new account of Kabbalistic thought that its followers synthesised with, and read into, the earlier Kabbalah of the Zohar that had disseminated in Medieval circles.

| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

Lurianic Kabbalah describes new doctrines of the origins of Creation, and the concepts of Olam HaTohu (Hebrew: עולם התהו "The World of Tohu-Chaos") and Olam HaTikun (Hebrew: עולם התיקון "The World of Tikun-Rectification"), which represent two archetypal spiritual states of being and consciousness. These concepts derive from Isaac Luria's interpretation of and mythical speculations on references in the Zohar.[1][2] The main popularizer of Luria's ideas was Rabbi Hayyim ben Joseph Vital of Calabria, who claimed to be the official interpreter of the Lurianic system, though some disputed this claim.[3] Together, the compiled teachings written by Luria's school after his death are metaphorically called "Kitvei HaARI" (Writings of the ARI), though they differed on some core interpretations in the early generations.

Previous interpretations of the Zohar had culminated in the rationally influenced scheme of Moses ben Jacob Cordovero in Safed, immediately before Luria's arrival. Both Cordovero's and Luria's systems gave Kabbalah a theological systemisation to rival the earlier eminence of Medieval Jewish philosophy. Under the influence of the mystical renaissance in 16th-century Safed, Lurianism became the near-universal mainstream Jewish theology in the early-modern era,[4] both in scholarly circles and in the popular imagination. The Lurianic scheme, read by its followers as harmonious with, and successively more advanced than the Cordoverian,[2] mostly displaced it, becoming the foundation of subsequent developments in Jewish mysticism. After the Ari, the Zohar was interpreted in Lurianic terms, and later esoteric Kabbalists expanded mystical theory within the Lurianic system. The later Hasidic and Mitnagdic movements diverged over implications of Lurianic Kabbalah, and its social role in popular mysticism. The Sabbatean mystical tradition would also derive its source from Lurianic messianism, but had a different understanding of the Kabbalistic interdependence of mysticism with Halakha Jewish observance.

The nature of Lurianic thought

Background

| Jewish mysticism |

|---|

|

The characteristic feature of Luria's theoretical and meditative system is his recasting of the previous, static hierarchy of unfolding Divine levels, into a dynamic cosmic spiritual drama of exile and redemption. Through this, essentially there became two historical versions of the theoretical-theosophical tradition in Kabbalah:

- Medieval Kabbalah and the Zohar as it was initially understood (sometimes called "Classical/Zoharic" Kabbalah), which received its systemisation by Moshe Cordovero immediately prior to Luria in the Early-Modern period

- Lurianic Kabbalah, the basis of modern Jewish mysticism, though Luria and subsequent Kabbalists see Lurianism as no more than an explanation of the true meaning of the Zohar

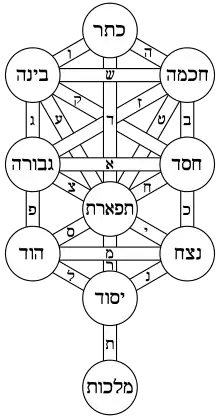

Earlier Kabbalah

The mystical doctrines of Kabbalah appeared in esoteric circles in 12th century Southern France (Provence-Languedoc), spreading to 13th century Northern Spain (Catalonia and other regions). Mystical development culminated with the Zohar's dissemination from 1305, the main text of Kabbalah. Medieval Kabbalah incorporated motifs described as "Neoplatonic" (linearly descending realms between the Infinite and the finite), "Gnostic" (in the sense of various powers manifesting from the singular Godhead, rather than plural gods) and "Mystical" (in contrast to rational, such as Judaism's first doctrines of reincarnation). Subsequent commentary on the Zohar attempted to provide a conceptual framework in which its highly symbolic imagery, loosely associated ideas, and seemingly contradictory teachings could be unified, understood, and organised systematically. Meir ben Ezekiel ibn Gabbai (born 1480) was a precursor in this, but Moshe Cordovero's (1522–1570) encyclopedic works influentially systemised the scheme of Medieval Kabbalah, though they did not explain some important classic beliefs such as reincarnation.[5] The Medieval-Cordoverian scheme describes in detail a linear, hierarchical process where finite Creation evolves ("Hishtalshelut") sequentially from God's Infinite Being. The sephirot (Divine attributes) in Kabbalah, act as discrete, autonomous forces in the functional unfolding of each level of Creation from potential to actual. The welfare of the Upper Divine Realm, where the sephirot are manifest supremely, is mutually bound up with the welfare of the Lower Human Realm. The acts of Man, at the end of the chain, affect harmony between the sephirot in the higher spiritual Worlds. Mitzvot (Jewish observances) and virtuous deeds bring unity Above, allowing unity between God and the Shekhinah (Divine Presence) Below, opening the Flow of Divine vitality throughout Creation. Sin and selfish deeds introduce disruption and separation throughout Creation. Evil, caused through human deeds, is a misdirected overflow Below of unchecked Gevurah (Severity) on High.

The early modern Safed community

The 16th century renaissance of Kabbalah in the Galilean community of Safed, which included Joseph Karo, Moshe Alshich, Cordovero, Luria and others, was shaped by their particular spiritual and historical outlook. After the 1492 Expulsion from Spain they felt a personal urgency and responsibility on behalf of the Jewish people to hasten Messianic redemption. This involved a stress on close kinship and ascetic practices, and the development of rituals with a communal-messianic focus. The new developments of Cordovero and Luria in systemising previous Kabbalah, sought mystical dissemination beyond the close scholarly circles to which Kabbalah had previously been restricted. They held that wide publication of these teachings, and meditative practices based on them, would hasten redemption for the whole Jewish people.

Lurianic Kabbalah

Where the messianic aim remained only peripheral in the linear scheme of Cordovero, the more comprehensive theoretical scheme and meditative practices of Luria explained messianism as its central dynamic, incorporating the full diversity of previous Kabbalistic concepts as outcomes of its processes. Luria conceptualises the Spiritual Worlds through their inner dimension of Divine exile and redemption. The Lurianic mythos brought deeper Kabbalistic notions to the fore: theodicy (primordial origin of evil) and exile of the Shekhinah (Divine Presence), eschatological redemption, the cosmic role of each individual and the historical affairs of Israel, symbolism of sexuality in the supernal Divine manifestations, and the unconscious dynamics in the soul. Luria gave esoteric theosophical articulations to the most fundamental and theologically daring questions of existence.[6]

Kabbalist views

Religious Kabbalists see the deeper comprehensiveness of Lurianic theory being due to its description and exploration of aspects of Divinity, rooted in the Ein Sof, that transcend the revealed, rationally apprehended mysticism described by Cordovero.[2] The system of Medieval Kabbalah becomes incorporated as part of its wider dynamic. Where Cordovero described the Sefirot (Divine attributes) and the Four spiritual Realms, preceded by Adam Kadmon, unfolding sequentially out of the Ein Sof, Luria probed the supra-rational origin of these Five Worlds within the Infinite. This revealed new doctrines of Primordial Tzimtzum (contraction) and the Shevira (shattering) and reconfiguration of the sephirot. In Kabbalah, what preceded more deeply in origins, is also reflected within the inner dimensions of subsequent Creation, so that Luria was able to explain messianism, Divine aspects, and reincarnation, Kabbalistic beliefs that remained unsystemised beforehand.

Cordovero and Medieval attempts at Kabbalistic systemisation, influenced by Medieval Jewish philosophy, approach Kabbalistic theory through the rationally conceived paradigm of "Hishtalshelut" (sequential "Evolution" of spiritual levels between the Infinite and the Finite - the vessels/external frames of each spiritual World). Luria systemises Kabbalah as a dynamic process of "Hitlabshut" ("Enclothement" of higher souls within lower vessels - the inner/soul dimensions of each spiritual World). This sees inner dimensions within any level of Creation, whose origin transcends the level in which they are enclothed. The spiritual paradigm of Creation is transformed into a dynamical interactional process in Divinity. Divine manifestations enclothe within each other, and are subject to exile and redemption:

The concept of hitlabshut ("enclothement") implies a radical shift of focus in considering the nature of Creation. According to this perspective, the chief dynamic of Creation is not evolutionary, but rather interactional. Higher strata of reality are constantly enclothing themselves within lower strata, like the soul within a body, thereby infusing every element of Creation with an inner force that transcends its own position within the universal hierarchy. Hitlabshut is very much a "biological" dynamic, accounting for the life-force which resides within Creation; hishtalshelut, on the other hand, is a "physical" one, concerned with the condensed-energy of "matter" (spiritual vessels) rather than the life-force of the soul.[7]

Due to this deeper, more internal paradigm, the new doctrines Luria introduced explain Kabbalistic teachings and passages in the Zohar that remained superficially understood and externally described before. Seemingly unrelated concepts become unified as part of a comprehensive, deeper picture. Kabbalistic systemisers before Luria, culminating with Cordovero, were influenced by Maimonides' philosophical Guide, in their quest to decipher the Zohar intellectually, and unify esoteric wisdom with Jewish philosophy.[8] In Kabbalah this embodies the Neshama (Understanding) mental level of the soul. The teachings of Luria challenge the soul to go beyond mental limitations. Though presented in intellectual terms, it remains a revealed, supra-rational doctrine, giving a sense of being beyond intellectual grasp. This corresponds to the soul level of Haya (Wisdom insight), described as "touching/not-touching" apprehension.[8]

Academic views

In the academic study of Kabbalah, Gershom Scholem saw Lurianism as a historically located response to the trauma of Spanish exile, a fully expressed mythologising of Judaism, and a uniquely paradoxically messianic mysticism, as mysticism phenomenologically usually involves withdrawal from community.[9] In more recent academia, Moshe Idel has challenged Scholem's historical influence in Lurianism, seeing it instead as an evolving development within the inherent factors of Jewish mysticism by itself.[10] In his monograph Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos: Isaac Luria and His Kabbalistic Fellowship, Stanford University Press, 2003, Lawrence Fine explores the world of Isaac Luria from the point of view of the lived experience of Luria and his disciples.

Concepts

Primordial Tzimtzum – Contraction of Divinity

Isaac Luria propounded the doctrine of the Tzimtzum, (meaning alternatively: "Contraction/Concealment/Condensation/Concentration"), the primordial Self-Withdrawal of Divinity to "make space" for subsequent Creation.

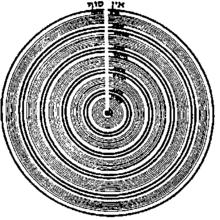

Previous Kabbalah taught that before the creation of the spiritual or physical realms, the Ein Sof ("Without End") Divine simplicity filled all reality. In a mystical form of Divine self-revelation, the Ohr Ein Sof ("Light of the Ein Sof/Infinite Light") shone within the Ein Sof, before any creation. In the absolute Unity of the Ein Sof, "no thing" (no limitation/end) could exist, as all would be nullified. About the Ein Sof, nothing can be postulated, as it transcends all grasp/definition. Medieval Kabbalah held that at the beginning of Creation, from the Ein Sof emerged from concealment the 10 Sephirot Divine attributes to emmanate existence. The vitality first shone to Adam Kadmon ("Primordial Man"), the realm of Divine Will), named metaphorically in relation to Man who is rooted in the initial Divine plan. From Adam Kadmon emerged sequentially the descending Four spiritual Realms: Atziluth ("Emanation" - the level of Divine Wisdom), Beriah ("Creation" - Divine Intellect), Yetzirah ("Formation" - Divine Emotions), Assiah ("Action" - Divine Realisation). In Medieval Kabbalah the problem of finite creation emerging from the Infinite was partially resolved by innumerable, successive tzimtzumim concealments/contractions/veilings of the Divine abundance down through the Worlds, successively reducing it to appropriate intensities. At each stage, the absorbed flow created realms, transmitting residue to lower levels.

To Luria, this causal chain did not resolve the difficulty, as the infinite quality of the Ohr Ein Sof, even if subject to countless veilings/contractions would still prevent independent existence. He advanced an initial, radical primordial Tzimtzum leap before Creation, the self-withdrawal of Divinity. At the centre of the Ein Sof, the withdrawal formed a metaphorical (non-spatial) Khalal/Makom Ponui ("Vacuum/Empty Space") in which Creation would take place. The vacuum was not totally empty, as a slight Reshima ("Impression") of the prior Reality remained, similar to water that clings to an emptied vessel.

Into the vacuum then shone a new light, the Kav ("Ray/Line"), a "thin" diminished extension from the original Infinite Light, which became the fountainhead for all subsequent Creation. While still infinite, this new vitality was radically different from the original Infinite Light, as it was now potentially tailored to the limited perspective of Creation. As the Ein Sof perfection encompassed both infinitude and finitude, so the Infinite Light possessed concealed-latent finite qualities. The Tzimtum allowed infinite qualities to retire into the Ein Sof, and potentially finite qualities to emerge. As the Kav shone into the centre of the vacuum it encompassed ten "concentric" Iggulim (the conceptual scheme of "Circles"), forming the sephirot, allowing the Light to appear in their diversity.

Shevira – Shattering of the sephirot vessels

The first divine configuration within the vacuum comprises Adam Kadmon, the first pristine spiritual realm described in earlier Kabbalah. It is the manifestation of the specific divine will for subsequent creation, within the relative framework of creation. Its anthropomorphic name metaphorically indicates the paradox of creation (Adam – man) and manifestation (Kadmon – primordial divinity). Man is intended as the future embodiment in subsequent creation, not yet emerged, of the divine manifestations. The Kav forms the sephirot, still only latent, of Adam Kadmon in two stages: first as Iggulim (Circles), then encompassed as Yosher (Upright), the two schemes of arranging the sephirot. In Luria's systematic explanation of terms found in classic Kabbalah:

- Iggulim is the sephirot acting as ten independent "concentric" principles;

- Yosher is a Partzuf (configuration) in which the sephirot act in harmony with each other in the three-column scheme.

"Upright" is so called by way of an analogy to the soul and body of man. In man the ten sephirotic powers of the soul act in harmony, reflected in the different limbs of the body, each with a particular function. Luria explained that it is the Yosher configuration of the sephirot that is referred to by Genesis 1:27, "God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him, male and female He created them". However, in Adam Kadmon, both configurations of the sephirot remain only in potential. Adam Kadmon is pure divine light, with no vessels, bounded by its future potential will to create vessels, and by the limiting effect of the Reshima.

From the non-corporeal figurative configuration of Adam Kadmon emanate five lights: metaphorically from the "eyes", "ears", "nose", "mouth" and "forehead". These interact with each other to create three particular spiritual world-stages after Adam Kadmon: Akudim ("Bound" – stable chaos), Nekudim ("Points" – unstable chaos), and Berudim ("Connected" – beginning of rectification). Each realm is a sequential stage in the first emergence of the sephirotic vessels, prior to the world of Atziluth (Emanation), the first of the comprehensive four spiritual worlds of creation described in previous Kabbalah. As the sephirot emerged within vessels, they acted as ten independent Iggulim forces, without inter-relationship. Chesed (Kindness) opposed Gevurah (Severity), and so with the subsequent emotions. This state, the world of Tohu (Chaos) precipitated a cosmic catastrophe in the Divine realm. Tohu is characterised by great divine Ohr (Light) in weak, immature, unharmonised vessels. As the divine light poured into the first intellectual sephirot, their vessels were close enough to their source to contain the abundance of vitality. However, as the overflow continued, the subsequent emotional sephirot shattered (Shevirat HaKeilim – "Shattering of the Vessels") from Binah (Understanding) down to Yesod (the Foundation) under the intensity of the light. The final sephirah Malkhut (Kingship) remains partially intact as the exiled Shekhina (feminine divine immanence) in creation. This is the esoteric account in Genesis[11] and Chronicles[12] of the eight Kings of Edom who reigned before any king reigned in Israel. The shards of the broken vessels fell down from the realm of Tohu into the subsequent created order of Tikun (Rectification), splintering into innumerable fragments, each animated by exiled Nitzutzot (Sparks) of their original light. The more subtle divine sparks became assimilated in higher spiritual realms as their creative lifeforce. The coarser animated fragments fell down into our material realm, with lower fragments nurturing the Kelipot (Shells) in their realms of impurity.

Partzufim – Divine Personas

The subsequent comprehensive Four spiritual Worlds of Creation, described in previous Kabbalah, embody the Lurianic realm of Tikun ("Rectification"). Tikun is characterised by lower, less sublime lights than Tohu, but in strong, mature, harmonised vessels. Rectification is first initiated in Berudim, where the sephirot harmonise their 10 forces by each including the others as latent principles. However, supernal rectification is completed in Atziluth (World of "Emanation") after the Shevira, through the sephirot transforming into Partzufim (Divine "Faces/Configurations"). In Zoharic Kabbalah the partzufim appear as particular supernal Divine aspects, expounded in the esoteric Idrot, but become systemised only in Lurianism. The 6 primary partzufim, which further divide into 12 secondary forms:

- Atik Yomin ("Ancient of Days") inner partzuf of Keter Delight

- Arikh Anpin ("Long Visage") outer partzuf of Keter Will

- Abba ("Father") partzuf of Chokhma Wisdom

- Imma ("Mother") partzuf of Binah Understanding

- Zeir Anpin ("Short Visage" - Son) partzuf of emotional sephirot

- Nukva ("Female" - Daughter) partzuf of Malkhut Kingship

The Parzufim are the sephirot acting in the scheme of Yosher, as in man. Rather than latently including other principles independently, the partzufim transform each sephirah into full anthropomorphic three-column configurations of 10 sephirot, each of which interacts and enclothes within the others. Through the parzufim, the weakness and lack of harmony that instigated shevirah is healed. Atziluth, the supreme realm of Divine manifestation and exclusive consciousness of Divine Unity, is eternally rectified by the partzufim; its root sparks from Tohu are fully redeemed. However, the lower three Worlds of Beri'ah ("Creation"), Yetzirah ("Formation") and Assiah ("Action") embody successive levels of self-consciousness independent of Divinity. Active Tikun rectification of lower Creation can only be achieved from Below, from within its limitations and perspective, rather than imposed from Above. Messianic redemption and transformation of Creation is performed by Man in the lowest realm, where impurity predominates.

This proceeding was absolutely necessary. Had God in the beginning created the partzufim instead of the Sefirot, there would have been no evil in the world, and consequently no reward and punishment; for the source of evil is in the broken Sefirot or vessels (Shvirat Keilim), while the light of the Ein Sof produces only that which is good. These five figures are found in each of the Four Worlds; namely, in the world of Emanation (atzilut), Creation (beri'ah), Formation (yetzirah), and in that of Action (asiyah), which represents the material world.

Birur – Clarification by Man

The task of rectifying the sparks of holiness that were exiled in the self-aware lower spiritual Worlds was given to Biblical Adam in the Garden of Eden. In the Lurianic account, Adam and Hava (Eve) before the sin of Tree of Knowledge did not reside in the physical World Assiah ("Action"), at the present level of Malkhut (lowest sephirah "Kingship"). Instead, the Garden was the non-physical realm of Yetzirah ("Formation"), and at the higher sephirah of Tiferet ("Beauty").[13]

Gilgul – Reincarnation and the soul

Luria's psychological system, upon which is based his devotional and meditational Kabbalah, is closely connected with his metaphysical doctrines. From the five partzufim, he says, emanated five souls, Nefesh ("Spirit"), Ru'ach ("Wind"), Neshamah ("Soul"), Chayah ("Life"), and Yechidah ("Singular"); the first of these being the lowest, and the last the highest. (Source: Etz Chayim). Man's soul is the connecting link between the infinite and the finite, and as such is of a manifold character. All the souls destined for the human race were created together with the various organs of Adam. As there are superior and inferior organs, so there are superior and inferior souls, according to the organs with which they are respectively coupled. Thus there are souls of the brain, souls of the eye, souls of the hand, etc. Each human soul is a spark (nitzotz) from Adam. The first sin of the first man caused confusion among the various classes of souls: the superior intermingled with the inferior; good with evil; so that even the purest soul received an admixture of evil, or, as Luria calls it, of the element of the "shells" (Kelipoth). In consequence of the confusion, the former are not wholly deprived of the original good, and the latter are not altogether free from sin. This state of confusion, which gives a continual impulse toward evil, will cease with the arrival of the Messiah, who will establish the moral system of the world upon a new basis.

Until the arrival of the Messiah, man's soul, because of its deficiencies, can not return to its source, and has to wander not only through the bodies of men and of animals, but sometimes even through inanimate things such as wood, rivers, and stones. To this doctrine of gilgulim (reincarnation of souls) Luria added the theory of the impregnation (ibbur) of souls; that is to say, if a purified soul has neglected some religious duties on earth, it must return to the earthly life, and, attaching itself to the soul of a living man, and unite with it in order to make good such neglect.

Further, the departed soul of a man freed from sin appears again on earth to support a weak soul which feels unequal to its task. However, this union, which may extend to two souls at one time, can only take place between souls of homogeneous character; that is, between those which are sparks of the same Adamite organ. The dispersion of Israel has for its purpose the salvation of men's souls; as the purified souls of Israelites will fulfill the prophecy of becoming "A lamplight unto the nations," influencing the souls of men of other races to do good. According to Luria, there exist signs by which one may learn the nature of a man's soul: to which degree and class it belongs; the relation existing between it and the superior world; the wanderings it has already accomplished; the means by which it can contribute to the establishment of the new moral system of the world; and to which soul it should be united in order to become purified.

Influence

Sabbatean mystical heresies

Lurianic Kabbalah has been accused by some of being the cause of the spread of the Sabbatean Messiahs Shabbetai Tzvi (1626–1676) and Jacob Frank (1726–1791), and their Kabbalistically based heresies. The 16th century mystical renaissance in Safed, led by Moshe Cordovero, Joseph Karo and Isaac Luria, made Kabbalistic study a popular goal of Jewish students, to some extent competing for attention with Talmudic study, while also capturing the hold of the public imagination. Shabbeteanism emerged in this atmosphere, coupled with the oppressions of Exile, alongside genuine traditional mystic circles.

Where Isaac Luria's scheme emphasised the democratic role of every person in redeeming the fallen sparks of holiness, allocating the Messiah only a conclusive arrival in the process, Shabbetai's prophet Nathan of Gaza interpreted his messianic role as pivotal in reclaiming those sparks lost in impurity. Now faith in his messianic role, after he apostasised to Islam, became necessary, as well as faith in his antinomian actions. Jacob Frank claimed to be a reincarnation of Shabbetai Tzvi, sent to reclaim sparks through the most anarchist actions of his followers, claiming the breaking of the Torah in his emerged messianic era was now its fulfilment, the opposite of the messianic necessity of Halakhic devotion by Luria and the Kabbalists. Instead, for the elite 16th century Kabbalists of Safed after the Expulsion from Spain, they sensed a personal national responsibility, expressed through their mystical renaissance, ascetic strictures, devoted brotherhood, and close adherence to normative Jewish practice.

Influence on ritual practice and prayer meditation

Lurianic Kabbalah remained the leading school of mysticism in Judaism, and is an important influence on Hasidism and Sefardic kabbalists. In fact, only a minority of today's Jewish mystics belong to other branches of thought in Zoharic mysticism. Some Jewish kabbalists have said that the followers of Shabbetai Tzvi strongly avoided teachings of Lurianic Kabbalah because his system disproved their notions. On the other hand, the Shabbetians did use the Lurianic concepts of sparks trapped in impurity and pure souls being mixed with the impure to justify some of their antinomian actions.

Luria introduced his mystic system into religious observance. Every commandment had a particular mystic meaning. The Shabbat with all its ceremonies was looked upon as the embodiment of the Divinity in temporal life, and every ceremony performed on that day was considered to have an influence upon the superior world. Every word and syllable of the prescribed prayers contain hidden names of God upon which one should meditate devoutly while reciting. New mystic ceremonies were ordained and codified under the name of Shulkhan Arukh HaARI (The "Code of Law of the Ari"). In addition, one of the few writings of Luria himself comprises three Sabbath table hymns with mystical allusions. From the third meal's hymn:

You princes of the palace, who yearn to behold the splendour of Zeir Anpin

Be present at this meal at which the King leaves His imprint

Exult, rejoice in this gathering together with the angels and all supernal beings

Rejoice now, at this most propitious time, when there is no sadness...

I herewith invite the Ancient of Days at this auspicious time, and impurity will be utterly removed...[14]

In keeping with the custom of engaging in all-night Torah study on the festival of Shavuot, Isaac Luria arranged a special service for the night vigil of Shavuot, the Tikkun Leil Shavuot ("Rectification for Shavuot Night"). It is commonly recited in synagogue, with Kaddish if the Tikkun is studied in a group of ten. Afterwards, Hasidim immerse in a mikveh before dawn.

Modern Jewish spirituality and dissenting views

Rabbi Luria's ideas enjoy wide recognition among Jews today. Orthodox as well as Reform, Reconstructionist and members of other Jewish groups frequently acknowledge a moral obligation to "repair the world" (tikkun olam). This idea draws upon Luria's teaching that shards of divinity remain contained in flawed material creation and that ritual and ethical deeds by the righteous help to release this energy. The mystical theology of the Ari does not exercise the same level of influence everywhere, however. Communities where Luria's thought holds less sway include many German and Modern Orthodox communities, groups carrying forward Spanish and Portuguese traditions, a sizable segment of Baladi Yemenite Jews (see Dor Daim), and other groups that follow a form of Torah Judaism based more on classical authorities like Maimonides and the Geonim.

With its Rationalist project, the 19th century Haskalah movement and the critical study of Judaism dismissed Kabbalah. In the 20th century, Gershom Scholem initiated the academic study of Jewish mysticism, utilising historical methodology, but reacting against what he saw as its exclusively Rationalist dogma. Rather, he identified Jewish mysticism as the vital undercurrent of Jewish thought, periodically renewing Judaism with new mystical or messianic impetus. The 20th century academic respect of Kabbalah, as well as wider interest in spirituality, bolster a renewed Kabbalistic interest from non-Orthodox Jewish denominations in the 20th century. This is often expressed through the form of Hasidic incorporation of Kabbalah, embodied in Neo-Hasidism and Jewish Renewal.

Contemporary traditional Lurianism

Study of the Kitvei Ha'Ari (writings of Isaac Luria's disciples) continues mostly today among traditional-form Kabbalistic circles and in sections of the Hasidic movement. Mekubalim mizra'chim (oriental Sephardi Kabbalists), following the tradition of Haim Vital and the mystical legacy of the Rashash (1720–1777, considered by Kabbalists to be the reincarnation of the Ari), see themselves as direct heirs to and in continuity with Luria's teachings and meditative scheme.

Both sides of the Hasidic-Mitnagdic schism from the 18th century, upheld the theological world view of Lurianic Kabbalah. It is a misconception to see the Rabbinic opposition to Hasidic Judaism, at least in its formative origin, as deriving from adherence to Rationalist Medieval Jewish philosophical method.[15] The leader of the Rabbinic Mitnagdic opposition to the mystical Hasidic revival, the Vilna Gaon (1720–1797), was intimately involved in Kabbalah, following Lurianic theory, and produced Kabbalistically focused writing himself, while criticising Medieval Jewish Rationalism. His disciple, Chaim Volozhin, the main theoretician of Mitnagdic Judaism, differed from Hasidism over practical interpretation of the Lurianic tzimtzum.[16] For all intents, Mitnagdic Judaism followed a transcendent stress in tzimtzum, while Hasidism stressed the immanence of God. This theoretical difference led Hasidism to popular mystical focus beyond elitist restrictions, while it underpinned the Mitnagdic focus on Talmudic, non-mystical Judaism for all but the elite, with a new theoretical emphasis on Talmudic Torah study in the Lithuanian Yeshiva movement.

The largest scale Jewish development based on Lurianic teaching was Hasidism, though it adapted Kabbalah to its own thought. Joseph Dan describes the Hasidic-Mitnagdic schism as a battle between two conceptions of Lurianic Kabbalah. Mitnagdic elite Kabbalah was essentially loyal to Lurianic teaching and practice, while Hasidism introduced new popularised ideas, such as the centrality of Divine immanence and Deveikut to all Jewish activity, and the social mystical role of the Tzadik Hasidic leadership.[17]

Literal and non-literal interpretations of the Tzimtzum

In the decades after Luria and in the early 18th century, different opinions formed among Kabbalists over the meaning of tzimtzum, the Divine self-withdrawal: should it be taken literally or symbolically? Immanuel Hai Ricci (Yosher Levav, 1736-7) took tzimtzum literally, while Joseph Ergas (Shomer Emunim, 1736) and Abraham Herrera held that tzimtzum was to be understood metaphorically.[18]

Hasidic and Mitnagdic views of the Tzimtzum

The issue of the tzimtzum underpinned the new, public popularisation of mysticism embodied in 18th century Hasidism. Its central doctrine of almost-Panentheistic Divine Immanence, shaping daily fervour, emphasised the most non-literal stress of the tzimtzum. The systematic articulation of this Hasidic approach by Shneur Zalman of Liadi in the second section of Tanya, outlines a Monistic Illusionism of Creation from the Upper Divine Unity perspective. To Schneur Zalman, the tzimtzum only affected apparent concealment of the Ohr Ein Sof. The Ein Sof, and the Ohr Ein Sof, actually remain omnipresent, this world nullified into its source. Only, from the Lower, Worldly Divine Unity perspective, the tzimtzum gives the illusion of apparent withdrawal. In truth, "I, the Eternal, I have not changed" (Malachi 3:6), as interpreting the tzimtzum with any literal tendency would be ascribing false corporeality to God.

Norman Lamm describes the alternative Hasidic-Mitnagdic interpretations of this.[19] To Chaim Volozhin, the main theoretician of the Mitnagdim Rabbinic opposition to Hasidism, the illusionism of Creation, arising from a metaphorical tzimtzum is true, but does not lead to Panentheism, as Mitnagdic theology emphasised Divine transcendence, where Hasidism emphasised immanence. As it is, the initial general impression of Lurianic Kabbalah is one of transcendence, implied by the notion of tzimtzum. Rather, to Hasidic thought, especially in its Chabad systemisation, the Atzmus ultimate Divine essence is expressed only in finitude, emphasising Hasidic Immanence.[20] Norman Lamm sees both thinkers as subtle and sophisticated. The Mitnagdim disagreed with Panentheism, in the early opposition of the Mitnagdic leader, the Vilna Gaon seeing it as heretical. Chaim Volzhin, the leading pupil of the Vilna Gaon, was at the same time both more moderate, seeking to end the conflict, and most theologically principled in his opposition to the Hasidic interpretation. He opposed panentheism as both theology and practice, as its mystical spiritualisation of Judaism displaced traditional Talmudic learning, as was liable to inspire antinomian blurring of Halachah Jewish observance strictures, in quest of a mysticism for the common folk.

As Norman Lamm summarises, to Schneur Zalman and Hasidism, God relates to the world as a reality, through His Immanence. Divine immanence - the Human perspective, is pluralistic, allowing mystical popularisation in the material world, while safeguarding Halacha. Divine Transcendence - the Divine perspective, is Monistic, nullifying Creation into illusion. To Chaim Volozhin and Mitnagdism, God relates to the world as it is through His transcendence. Divine immanence - the way God looks at physical Creation, is Monistic, nullifying it into illusion. Divine Transcendence - the way Man perceives and relates to Divinity is pluralistic, allowing Creation to exist on its own terms. In this way, both thinkers and spiritual paths affirm a non-literal interpretation of the tzimtzum, but Hasidic spirituality focuses on the nearness of God, while Mitnagdic spirituality focuses on the remoteness of God. They then configure their religious practice around this theological difference, Hasidism placing Deveikut fervour as its central practice, Mitnagdism further emphasising intellectual Talmudic Torah study as its supreme religious activity.

See also

References

- ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 11, pg 617

- The Development of Kabbalah in Three Stages from inner.org: 1 Cordoverian Kabbalah - Hishtalshelut Evolution of Spiritual Worlds, 2 Lurianic Kabbalah - Hitlabshut Enclothement within Spiritual Worlds, 3 Hasidic thought - Hashra'ah Divine Omnipresence

- Fine 2003, p. 343-344, "Vital must have viewed Ibn Tabul's literary activities as an arrogant attempt to usurp his own authority as the sole legitimate repository and interpreter of Lurianic Kabbalah. We do not know how Ibn Tabul felt about Vital. Competition and jealousy between them was not, however, limited to the literary sphere. Both sought to succeed Luria, in the sense that, each also saw himself as a teacher of the Lurianic tradition. Three years after Luria's death, in 1575, Vital formed a group of seven individuals who agreed to study Lurianic teachings with him alone and not to share them with others.[117] Needless to say, Ibn Tabul was not a member of this group. Scholem speculated, in fact, that part of Vital's motivation in creating this circle was precisely to marginalize Ibn Tabul.[118] We know, of course, from the letters of Ibn Tabul's students Samuel Bacchi that Ibn Tabul had a group of disciples as well. Whereas Vital's fellowship survived for a very short time, leaving no evidence that he inspired true allegiance, Ibn Tabul gained a reputation as a charismatic teacher, at least some of whose disciples were intensely attached to him."

- Notes on the Study of Later Kabbalah in English: The Safed Period & Lurianic Kabbalah, p 1, Don Karr, quoting Gershom Scholem (Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 3rd edition, London: Thames & Hudson,

1955—pages 285-6):

The Lurianic Kabbalah was the last religious movement in Judaism the influence of which became preponderant among all sections of Jewish people and in every country of the Diaspora, without exception.

- from inner.org: "We can now understand why the doctrine of gilgul (reincarnation) does not appear anywhere within the system of the Ramak (Cordovero). Having not identified Hitlabshut ("Enclothement") as part of his conceptual focus, the entire issue remains premature and in need of the Ari's future elaboration.

- Kabbalah, A Very Short Introduction, Joseph Dan, Oxford University Press, chapter on Early Modern Developments: Safed and Lurianic Kabbalah. One example is the opening of Etz Hayim by Haim Vital, the main text of Lurianic thought. It begins with 2 "Hakirot" (investigations): "Why did God create the World?" and the seemingly mysterious "Why did God create the World when He did?"

- The Development of Kabbalistic Thought: Enclothement (Hitlabshut) and the Kabbalah of the Ari from inner.org

- Five Stages in the Historical Development of Kabbalah in relation to its texts, from inner.org: 1 Sefer Yetzirah - Nefesh action, 2 Zohar - Ruah emotion, 3 Pardes Rimonim (Cordovero) - Neshamah understanding, 4 Etz Haim (Lurianic Kabbalah) - Haya wisdom, 5 Tanya (Hasidic thought) - Yehida Divine unity

- Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, Gershom Scholem, Schocken. Seventh lecture: Isaac Luria and his school

- Kabbalah: New Perspectives, Moshe Idel, Yale University Press

- Genesis 36:31

- I Chronicles 1:43

- Converting the Wisdom of the Nations Part 1 from inner.org, section "The Origin of the Sparks"

- Sidur Tehillat HaShem, Habad Lurianic text, Kehot pub. English translation, p 211

- Kabbalah: A Very Short Introduction, Joseph Dan, Oxford University Press: Chapter on Modern Hasidism

- Torah Lishmah: Study of Torah for Torah's Sake in the Work of Rabbi Hayyim Volozhin and his Contemporaries, Norman Lamm, Ktav pub.

- Kabbalah:A Very Short Introduction, Joseph Dan

- Which Lurianic Kabbalah?, Don Karr

- Torah Lishmah: Study of Torah for Torah's Sake in the Work of Rabbi Hayyim Volozhin and his Contemporaries Ktav pub. Philosophical difference summarised in "Monism for Moderns" in Faith & Doubt: Studies in Traditional Jewish Thought Ktav

- On the Essence of Chasidus, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Kehot pub.