Security for the 2012 Summer Olympics

The security preparations for the 2012 Summer Olympics—with the exception of the air counter-terrorist plan, which was a RAF responsibility—was led by the police, with 13,000 officers available, supported by 17,000 members of the armed forces. Royal Navy, Army and RAF assets, including ships situated in the Thames, Typhoon jets, radar, helicopter-borne snipers, and surface-to-air missiles, were deployed as part of the security operation. The final cost of the security operation was estimated £553m (pounds sterling).

| Part of a series on |

The budget for venue security was being partly funded by the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG) as well as using the contingency from the £9.3 billion infrastructure budget. Private security firm G4S, enduring scandals regarding training and manpower that emerged mere weeks before the games, provided only about 10,000 staff, instead of their intended 13,700.

This was the biggest security operation Britain had faced for decades, with 40,000 security personnel. On 7 July 2005, the day after the city was selected to host the Olympics, the London Underground and a London bus had been attacked by terrorist group Al-Qaeda.

Air defences

The air security plan was a multi-layered construct intended to defeat the full range of potential air threats to the Games, from airliners, through light aircraft and micro-lights to drones. It involved the classification of airspace over London, requiring specific advanced permission to enter. Command and Control of air counter-terrorism is the responsibility of the Chief of the Air Staff and was exercised for the Olympics on his behalf by Air Officer Commanding 1 Group RAF, Air Vice-Marshal Stu Atha, the Olympics Air Component Commander. The air security plan was a modification of the existing air counter-terrorism measures for the whole UK that are continuously applied by the RAF.

At the core of the air security plan was the basing of RAF Eurofighter Typhoon fighters at RAF Northolt in West London. These were held at extremely high readiness to allow a rapid reaction to any potential threat, and were in addition to the Typhoons that maintain Quick Reaction Alert at RAF Coningsby and RAF Leuchars (now RAF Lossiemouth). The next layer of defences comprised RAF Regiment snipers, who would operate against small, slow air targets. They would be carried by RAF Puma helicopters (temporarily based at Ilford Territorial Army Centre) and Royal Navy and Army Lynx helicopters embarked on HMS Ocean, which was alongside at Greenwich on the River Thames). There were six sites, four using Rapier and two using Starstreak Fire units. After initially announcing the possibility of installing missiles the British government confirmed they would be deployed from mid July.[1]

Airspace management and early warning of a threat was provided using existing air traffic control and air defence radar, supplemented by mobile radar, including Type 101 ground-based radar from the RAF's 1 Air Control Centre, deployed to Kent. In addition, RAF E-3 Sentry Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft from RAF Waddington and Royal Navy Sea King Air Surveillance and Control System (ASACS), temporarily based at RAF Northolt, provided further early warning cover. A further layer of visual warning was provided by Royal Artillery observers at 28 locations around London, equipped with alerting devices and binoculars.[2]

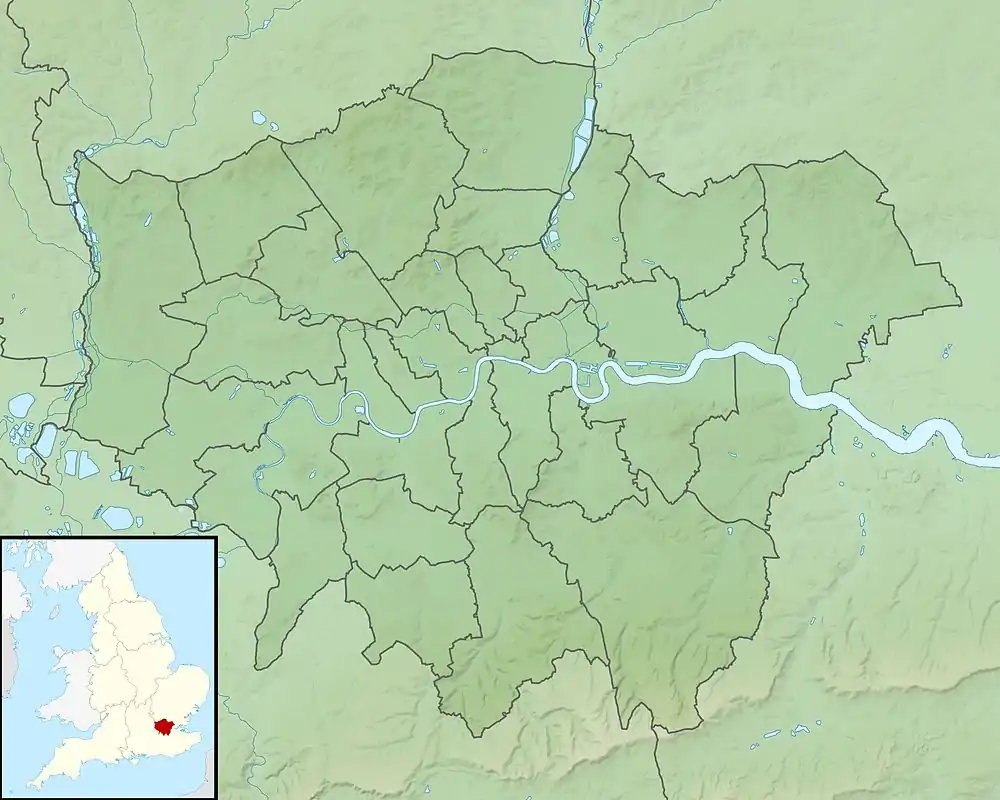

Rapier missiles are surface-to-air missiles designed to shoot down aeroplanes. It is a short-range air defence system, consisting of eight missiles with a tracking radar and a surveillance radar.[3] There were four Rapier sites, two in north London and two in south London.

The Rapier sites were:

- Blackheath Common[4]

- Oxleas Wood, Eltham[4]

- William Girling Reservoir, Enfield[4]

- Barn Hill, Netherstone Farm, near Epping Forest[4][5]

In addition two sites were selected for Starstreak missiles. They were at the top of tall buildings closer to the Olympic Stadium. One of the sites was the water tower of a factory converted into upmarket flats in Bow.[6] The other was a 15-storey block of council flats in Leytonstone. The residents of the latter took the government to court to protest against the siting of the missile battery, a case they lost on 10 July 2012.[7][8][9]

The Starstreak sites were:

- Lexington Building, Bow Quarter in LB Tower Hamlets[4]

- Fred Wigg Tower in Leytonstone, LB Waltham Forest[4]

The defences were tested in a large training exercise during 2–10 May 2012, known as Exercise Olympic Guardian, which preceded the operational phase of the campaign. The exercise involved Boeing E-3 Sentry from RAF Waddington, VC-10 tanker aircraft from RAF Brize Norton and Typhoon fast jets from 3(F) Sqn operating from RAF Northolt, the first time fighter aircraft had been stationed at the West London base since the Second World War.[2]

From 14 July 2012, Royal Air Force, Army and Navy assets and personnel began enforcing a 30-mile exclusion zone over London and other areas.[10]

Maritime defences

The Royal Navy and Royal Marines were equipped with the Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD), which uses directional sound as an anti-personnel weapon.[11] It was attached to a landing craft on the Thames at Westminster, and was to be used primarily in loud-hailer mode as a so-called acoustic hailing device, rather than as a weapon.[11] Royal Marines operated from HMS Ocean in small craft armed with conventional weapons.[11]

IT Security

BT was responsible for the IT infrastructure for the Olympics, and for securing the network perimeter against electronic attacks. The company had been warned to expect a high intensity of complex and determined attacks, but instead found that the attacks were "unsophisticated and perpetrated by children". When monitoring social media and chat sites for information on which targets might be attacked next, BT staff observed one would-be hacker breaking off a planning session because their mother was calling them to eat their tea, and another defending their technical performance by saying "what do you expect, I’m only 12?". The other main IT security obstacle encountered was the requirement to allow over 25,000 journalists access to network services; many of their computers were infected with viruses or other malware. BT contacted a number of spam blacklisting companies to explain the resulting increase in spam from its network.[12]

Preparation concerns

After it emerged in July 2012 that G4S, the company in charge of providing security, was unable to train enough security staff, an additional 3,500 sailors, soldiers and airmen were assigned to security duties at the Olympics.[13][14]

Lord Coe, chairman of LOCOG, said that the security of the Olympics had not been compromised as a result.[15]

Incidents

A few months before the games opened, Michael Shrimpton, a former immigration judge, contacted authorities to warn of an impending attack against the Games. According to Shrimpton, a German intelligence agency had stolen a nuclear warhead from a sunken Russian submarine and planted it in London. The agency was supposedly planning to detonate the warhead during the Games' opening ceremony. Shrimpton's report was treated seriously by police and, when it was found to be a hoax, he was arrested, tried, and convicted on two counts of communicating false information with intent. He was sentenced to twelve months' imprisonment.[16][17][18][19]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Security at the 2012 Summer Olympics. |

- "London 2012: Olympic missiles sites confirmed". BBC News. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- RAF News, 18 May 2012

- "Press Information:JERNAS" (PDF). MDBA Missile Systems. September 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Davenport, Justin (30 April 2012). "Ring of Missile Sites in Capital". London Evening Standard. pp. 1, 4–5.

- "WALTHAM ABBEY: Farm owner defends missile base". Waltham Forest Guardian. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- "UK puts missiles on London rooftop to guard Olympics". Reuters. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- "London 2012: Missile tower block tenants drop legal bid". BBC News. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Booth, Robert (29 April 2012). "London rooftops to carry missiles during Olympic Games". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "London Olympics 2012: MoD rooftop missile base plan alarms local residents". The Daily Telegraph. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "UK Armed Forces Enforce Olympic Airspace Limits". Armed Forces International. 13 July 2012.

- Thomas, Gavin (11 May 2012). "'Sonic weapon' deployed in London during Olympics". BBC News Online. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Muncaster, Phil (21 November 2012). "BT: Olympics cyber attackers were amateurs". The Register. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Burns, John F. (14 July 2012). "Amid Reports of Ineptitude, Concerns Over Security at London Olympics". The New York Times.

- Magnay, Jacquelin; Kirkup, James (13 July 2012). "London 2012 Olympics: Games could need more troops, Lord Coe suggests". The Daily Telegraph.

- "London 2012 security not compromised, says Coe". BBC News. 15 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- O'Keeffe, Hayley (6 February 2015). "Jail for pervert barrister who said nuclear bomb would blow up the Queen at the London Olympics". Bucks Herald. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "Barrister sparked security scare by 'claiming Nazis wanted to blow up the Queen at the 2012 Olympics'". The Telegraph. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Colley, Andrew (6 February 2015). "Barrister Michael Shrimpton, from Wendover, made claims in the build up to London Olympic Games". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- "Barrister jailed for Nazi Olympics bomb hoax call". The Scotsman. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2016.