Second Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. Philip was defeated and was forced to abandon all possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor. During their intervention, although the Romans declared the "freedom of the Greeks" against the rule from the Macedonian kingdom, the war marked a significant stage in increasing Roman intervention in the affairs of the eastern Mediterranean, which would eventually lead to Rome's conquest of the entire region.

| Second Macedonian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Macedonian Wars | |||||||||

The campaigns and battles of the Second Macedonian War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Publius Sulpicius Galba Titus Flamininus Attalus I |

| ||||||||

Background

In 204 BC King Ptolemy IV Philopator of Egypt died, leaving the throne to his six-year-old son Ptolemy V. Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus the Great of the Seleucid Empire decided to exploit the weakness of the young king by taking Ptolemaic territory for themselves and they signed a secret pact defining spheres of interest, opening the Fifth Syrian War. Philip first turned his attention to the independent Greek city states in Thrace and near the Dardanelles. His success at taking cities such as Kios worried the state of Rhodes and King Attalus I of Pergamon who also had interests in the area.

In 201 BC, Philip launched a campaign into Asia Minor, besieging the Ptolemaic city of Samos and capturing Miletus. Again, this disconcerted Rhodes and Attalus and Philip responded by ravaging Attalid territory and destroying the temples outside the walls of Pergamon.[1] Philip then invaded Caria but the Rhodians and Pergamenians successfully blockaded his fleet in Bargylia, forcing him to spend the winter with his army in a country which offered very few provisions.

At this point, although they appeared to have the upper hand, Rhodes and Pergamon still feared Philip so much that they sent an appeal to the rising power of Rome, which had just emerged victorious from the Second Punic War against Carthage. The Romans had previously fought the First Macedonian War against Philip V over Illyria, which had been resolved by the Peace of Phoenice in 205 BC. Very little in Philip's recent actions in Thrace and Asia Minor could be said to concern the Roman Republic directly. The Senate passed a supportive decree and Marcus Valerius Laevinus was sent to investigate.[2]

Earlier in 201 BC, Athens' relations with Philip had suddenly deteriorated. A pair of Acarnanians had entered the Temple of Demeter during the Eleusinian Mysteries and the Athenians had put them to death. In response, the Acarnanian League launched a raid on Attica, aided by Macedonian troops which they had received from Philip V. Shortly after this, King Attalus I arrived in Athens with Rhodian ambassadors and convinced the Athenians, who had maintained strict neutrality since the end of the Chremonidean War, to declare war on Macedon. Attalus sailed off, bringing most of the Cycladic islands over to his side and sent embassies to the Aetolian League in the hope of bringing them into the war as well. In response to the Athenian declaration of war, Philip dispatched a force of 2,000 infantry and 200 cavalry under the command of Philokles to invade Attica and place the city of Athens under siege.[3]

Course of the war

Rome enters the war (200 BC)

On 15 March 200 BC, new consuls, Publius Sulpicius Galba and Gaius Aurelius Cotta took office in Rome. In light of reports from Laevinus and further embassies from Pergamon, Rhodes, and Athens, the task of dealing with the troubles in Macedonia was allotted to Sulpicius. He called an assembly of the Comitia centuriata, the body with the legal power to make declarations of war. The Comitia nearly unanimously rejected his proposed war, an unprecedented act which was attributed to war weariness. At a second session, Sulpicius convinced the Comitia to vote for war.[4] Sulpicius recruited troops and departed to Brundisium in the autumn, where he added veterans of the Second Punic War who had just returned from Africa to his forces. Then he crossed the Adriatic, landing his troops in Apollonia and stationing the navy at Corcyra.[5]

Siege of Abydos

While these events had been taking place, Philip V himself had undertaken another campaign in the Dardanelles, taking a number of Ptolemaic cities in rapid succession before besieging the important city of Abydos. Polybius reports that during the siege of Abydos, Philip had grown impatient and sent a message to the besieged that the walls would be stormed and that if anybody wished to commit suicide or surrender they had three days to do so. The citizens promptly killed all the women and children of the city, threw their valuables into the sea and fought to the last man.[6] During the siege of Abydos, in the autumn of 200 BC, Philip was met by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, a Roman ambassador on his way back from Egypt,[7] who urged him not to attack any Greek state or to seize any territory belonging to Ptolemy and to go to arbitration with Rhodes and Pergamon. Philip protested that he was not in violation of any of the terms of the Peace of Phoenice, but in vain. As he returned to Macedonian after the fall of Abydos, he learnt of the landing of Sulpicius' force in Epirus.[8]

Cento's attack on Chalcis and Philip's invasion of Attica

The Athenians, who were now besieged by Macedonian forces, sent an appeal to the Roman force in Corcyra. Gaius Claudius Centho was sent with 20 ships and 1,000 men to aid them. Philokles and his troops withdrew from Attica to their base in Corinth. In response to a request from Chalcidean exiles, Claudius led a surprise raid on the city of Chalcis in Euboea, one of the key Antigonid strongholds known as the 'fetters of Greece' and inflicting serious damage and heavy casualties.[9]

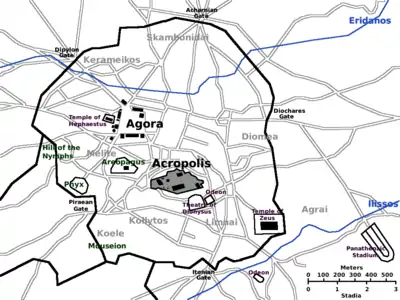

Philip rushed to Chalcis with a force of 5,000 men and 300 cavalry. Finding that Claudius had already withdrawn, he sped on towards Athens, where he defeated the Athenian and Attalid troops in a battle outside the Dipylon Gate and encamped at Cynosarges. After setting fire to the sanctuaries and tombs outside the city walls, Philip departed to Corinth. From there, Philip went down to Argos where the Achaean League was holding an assembly, which he attempted to bring onto his side in exchange for supporting them in their ongoing conflict with Nabis of Sparta, but he was rebuffed. Joining up with a force of 2,000 men brought by his general Philokles, Philip made a series of three unsuccessful assaults on Eleusis, Piraeus, and Athens and ravaged the territory of Athens. Then he ravaged the sanctuaries throughout Attica and withdrew to Boeotia.[10] The damage to the rural and deme sanctuaries of Attica was severe and marks the permanent end of their use.[11]

Philip spent the rest of the winter preparing for the Roman assault. He sent his young son Perseus with a force to prevent the Romans and Dardanians from advancing over the Šar Mountains into northern Macedonia. Philip had the settlements on the Sporades islands of Peparethos and Skiathos destroyed to prevent enemies using them as naval bases. The Macedonian army was gathered at Demetrias.[12]

Sulpicius' invasion of Upper Macedonia

During this time Sulpicius had established a firm base by the Seman river in Illyria. A force under Lucius Apustius was sent to raid the western border of Macedonia, capturing or razing a number of cities, including Antipatrea and Codrion. Following this expedition, Sulpicius received the allegiance of the Illyrians under Scerdilaidas, the Dardanians under Bato, and the Athamanes under Amynander. The diplomatic efforts of Philip, Sulpicius, and the Athenians centred on the Aetolian League, which seemed inclined to support the Romans but remained neutral at this stage.[13]

At the end of winter in 200 BC, Sulpicius led his troops east through the territory of the Dassaretae. Philip gathered 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, recalling the troops he had stationed in the north with Perseus, and marched west. He encamped on a hill near Athacus which overlooked Sulpicius' camp. After a series of indecisive skirmishes (in one of which Philip was nearly captured), news came that the Dardanians had invaded northern Macedonia, and the Macedonians withdrew secretly in the night.[14] When he realised what had happened, Sulpicius set out in pursuit through Pelagonia, found Philip blocking the pass to Eordaea and forced it. Sulpicius ravaged Eordaea, then Elimeia to the south, and then followed the Haliacmon river valley up to Orestis, where he conquered Celetrum and Pelion and then returned to his base.[15] Philip split his force, sending a contingent of his army north to deal with the Dardanian invasion, which it did, while he himself headed south.

Roman naval campaign and Aetolian campaign

At the same time as this land campaign set out, the Roman fleet had left Corcyra under command of Lucius Apustius, rounded Cape Malea, and rendezvoused with King Attalus near Hermione. The combined fleet then launched an assault on the Macedonian military base on the island of Andros and seized it for Pergamon. The fleet was joined by further ships from Issa and Rhodes and headed north to the Chalkidike peninsula where an assault on Cassandreia was a complete failure. They withdrew to northern Euboea, where they besieged and captured Oreus, another key Macedonian naval base. Since it was now autumn and the sailing season was drawing to a close, the contingents of the fleet dispersed back to their home ports.[16]

As these campaigns progressed, Damocritus, the strategos of the Aetolian League, had decided that it was time to join the war on the Roman side. Together with King Amynander, he led an invasion of Magnesia and Perrhaebia, then continued to ravage Thessaly. There, Philip suddenly appeared and completely defeated their force. He spent some time besieging the Aetolian city of Thaumaci, but gave up and withdrew as winter approached. He spent the winter training his army and engaging in diplomacy, particularly with the Achaean League.[17]

Villius' campaign

In Rome, the new consuls took office on 15 March 199 BC, Publius Villius Tappulus was allotted Macedonia as his province. He crossed the Adriatic to Corcyra, where he replaced Sulpicius in command of the army.[18] On his arrival, Villius faced a mutiny by 2,000 troops, veterans of the Second Punic War who wished to be demobilised. He resolved this, by forwarding their concerns to the Senate, but was left with little time to prosecute a campaign.[19] Philip marched west and encamped on both sides of the Aoös river where it passed through a narrow ravine. Villius marched to meet him, but was still considering what to do when he learnt that his successor, Titus Quinctius Flamininus had been elected and was on his way to Corcyra to assume command.[20]

In Asia Minor, Pergamon was invaded by the Seleucid king Antiochus III. As a result, Attalus was not able to assist in the naval war in the Aegean until a Roman embassy forced Antiochus to withdraw.[21]

Roman invasion of Thessaly

When the new consuls took office on 15 March 198, the Senate ordered the recruitment of 8,000 new infantry and 800 cavalry for the war. Command in Macedonia was allotted to Flamininus.[22] He was not yet thirty and was a self-proclaimed Philhellene.

Flamininus was delayed by religious matters for some time, but then he recruited the new forces, crossed the Adriatic, and dismissed Villius. The army encamped in the Aous Valley, across the river from Philip's for forty days.[23] At a peace conference, Flamininus announced the Romans' new peace terms. Up to this point, the Romans had merely ordered Philip to stop attacking the Greek cities. Now Flamininus demanded that he should make reparations to all the Greek cities he had harmed and withdraw all his garrisons from cities outside Macedonia, including Thessaly, which had been part of the Macedonian kingdom continuously since 353 BC. Philip stormed out of the meeting in anger and Flamininus decided to attack.[24]

In the subsequent Battle of the Aous, Flamininus was victorious despite the advantage the terrain gave to the Macedonian army, when he was shown a pass through the mountains which allowed him to send a force to attack the Macedonians from the rear. The Macedonian force collapsed and fled, suffering 2,000 casualties. Philip was able to gather up the survivors and retreat to Thessaly.[25] There he destroyed the city of Tricca to prevent it falling into Roman hands and withdrew to Tempe.[26]

After the Roman victory, the Aetolians led a rapid attack through Ainis and into Dolopia, while King Amynander attacked and captured Gomphi, in the south-western corner of Thessaly. Meanwhile, Flamininus entered Epirus, which now joined the Roman side. Together with Amynander, he entered Thessaly.[27] The army did not encounter much resistance at first, but he became caught up in a prolonged siege at Atrax. Eventually he was forced to abandon this siege and march south into Phocis in order to secure his supply lines and lodgings for winter by capturing Anticyra.[28] He then besieged and captured Elateia.[29]

Roman naval campaign

While this campaign was taking place, the consul's brother, Lucius Quinctius Flamininus had taken control of the Roman fleet and sailed to Athens. He rendezvoused with the Attalid and Rhodian fleets near Euboea. Eretria was taken after fierce fighting and Carystus surrendered, meaning that the entire island of Euboea was now under Roman control. The fleet travelled back around Attica to Cenchreae and placed Corinth under siege.[30]

From there, Lucius, Attalus, the Rhodians, and the Athenians sent ambassadors to the Achaian League in order to bring them into the war on the Roman side. The league held an assembly at Sicyon to decide how to respond, which was extremely contentious. On the one hand, the Achaians were still at war with Sparta and they were allied to Macedonia, but on the other hand their new chief magistrate Aristaenus was pro-Roman and the Romans promised to give the city of Corinth to the League. The representatives of Argos, Megalopolis, and Dyme, which all had particularly strong ties with Philip, left the meeting. The rest of the assembly voted to join the anti-Macedonian alliance.[31]

The Achaian army joined the other forces besieging Corinth, but after fierce fighting the siege had to be abandoned when 1,500 Macedonian reinforcements commanded by Philokles arrived from Boiotia.[32] From Corinth, Philokles was invited to take control of Argos by pro-Macedonians in the city, which he did without a fight.[33]

Winter negotiations

Over the winter of 198/197 BC, Philip declared his willingness to make peace. The parties met at Nicaea in Locris in November 198 - Philip sailed from Demetrias, but he refused to disembark and meet Flamininus and his allies on the beach, so he addressed them from the prow of his ship. To prolong the proceedings, Flamininus insisted that all his allies should be present at the negotiations. He then reiterated his demands that Philip should withdraw all his garrisons from Greece, Illyria, and Asia Minor. Philip was not prepared to go this far and he was persuaded to send an embassy to the Roman Senate. When this embassy reached Rome, the Senate demanded that Philip surrender the "fetters of Greece," Demetrias, Chalcis, and Corinth, but Philip's envoys claimed they had no permission to agree to this, so the war continued.[34]

According to Polybius and Plutarch, these negotiations were manipulated by Flamininus - Philip's overtures had come just as elections were being held in Rome. Flamininus was eager to take the credit for ending the war but he did not yet know whether his command would be prolonged and had intended to make a quick peace deal with Philip, if it was not. He therefore dragged out the negotiations until he learnt that his command had been prorogued and then had his friends in Rome scupper the meeting in the Senate.[35]

Once this had become clear, Philip attempted to free up his forces by handing the city of Argos over to Nabis of Sparta, but Nabis then engineered a revolution in the city and organised a conference with Flamininus, Attalus and the Achaeans at Mycenae, at which he agreed to stop attacking the Achaeans and to supply troops to the Romans.[36]

Flamininus' second campaign (197 BC)

Over the rest of the winter, Philip mobilised all the manpower of his kingdom including the aged veterans and the underage men, which amounted to 18,000 men. To these he added 4,000 peltasts from Thrace and Illyria, and 2,500 mercenaries. All these forces were gathered at Dion.[37] Reinforcements were sent to Flamininus from Italy, numbering 6,000 infantry, 300 cavalry, and 3,000 marines.[38]

At the start of spring, Flamininus and Attalus went to Thebes to bring the Boeotian League into the coalition. Because Flamininus had managed to sneak 2,000 troops into the city, the assembly of the League had no choice but to join the Roman coalition. At the assembly, King Attalus suddenly suffered a stroke while giving a speech and was left paralysed on one side. He was eventually evacuated back to Pergamon, where he died later that year.[39]

In June 197 BC, Flamininus marched north from Elateia through Thermopylae. En route, he was joined by forces from Aetolia, Gortyn in Crete, Apollonia, and Athamania.[40] Philip marched south into Thessaly and the two armies encamped opposite each other near Pherae. Both armies relocated to the hills around Scotussa. Contingents of the opposing armies came into contact with one another in the Cynoscephalae hills, leading to a full battle. In what proved to be the decisive engagement of the war, the legions of Flamininus defeated Philip's Macedonian phalanx. Philip himself fled on horseback, collected the survivors, and withdrew to Macedonia. Philip was forced to sue for peace on Roman terms.[41]

Achaia, Acarnania, and Caria

At the same time as this campaign was taking place in Thessaly, three other campaigns occurred in Achaea, Acarnania, and Caria - in all of which the Macedonians were defeated.

In the Peloponnese, Androsthenes set out from Corinth with a Macedonian army of 6,000 men into the lands controlled by the Achaean League and pillaged the territories of Pellene, Phlius, Cleonae, and Sicyon. The Achaean general, Nicostratus, who was able to muster 5,000 men, closed off the pass back to Corinth, and defeated the Macedonian forces in detail.[42]

In Acarnania, there had been attempts to switch to the Roman side before the Battle of Cynoscephalae, but the League's assembly had eventually decided against this because of their hostility to the Aetolians. Lucius Flamininus therefore sailed to the Acarnanian capital of Leucas, and launched an all-out assault, which proved very difficult. Thanks to traitors inside the city, it was eventually captured. Shortly after this, news of the Battle of Cynoscephalae arrived and the rest of the Acarnanians surrendered.[43]

In Asia Minor, the Rhodians led a force of 4,500 mercenaries (mostly Achaeans) into Caria to recapture the Rhodian Peraia. A battle took place with the Macedonian forces in the area at Abanda, in which the Rhodians were victorious. The Rhodians then recaptured their Peraia, but failed to take Stratonicea.[44]

Aftermath

The Peace of Flamininus

An armistice was declared and peace negotiations were held in the Vale of Tempe. Philip agreed to evacuate the whole of Greece and relinquish his conquests in Thrace and Asia Minor.[45] Philip had to rush off almost immediately after the agreement of terms to deal with an invasion of Upper Macedonia by the Dardanians.[46]

The treaty was sent to Rome for ratification. Despite the efforts of the consul-elect Marcus Claudius Marcellus to prolong the war, the Roman Tribal Assembly voted unanimously to make peace. The Senate sent ten commissioners to advise on the final peace terms, including Publius Sulpicius Galba and Publius Villius Tappulus.[47]

On the advice of these men, the final peace was made with Philip in spring 196 BC. Philip had to remove all his garrisons in Greek cities in Europe and Asia, which were to be free and autonomous. Philip had to pay a war indemnity of 1,000 talents - half paid immediately and the rest in ten annual instalments of 50 talents. He had to surrender his whole navy except for his flagship, while his army was limited to a maximum of 5,000 men, could not include elephants, and could not be led beyond his borders without permission of the Roman Senate.[48]

Boeotian campaign

Over the winter of 197/196 BC, while the peace negotiations were still ongoing, conflict had broken out in Boeotia, leading to the assassination of the pro-Macedonian Boeotarch Brachylles by the pro-Roman leaders Zeuxippus and Peisistratus. There was a strong popular backlash, resulting in the murder of about 500 Roman soldiers who had been billeted in Boeotia. Roman forces invaded Boeotia, but the Athenians and Achaeans managed to negotiate a settlement.[49]

Aetolian response to the peace

At the initial peace negotiations, a rift opened up between Flamininus and the Aetolians, since the latter wanted harsher peace terms imposed on Philip than Flamininus was willing to countenance and desired the return of a number of cities that they had previously controlled in Thessaly but Flamininus refused to back them.[50] The Aetolians began to claim that the Romans planned to retain garrisons in the "fetters of Greece" and replace the Macedonians as overlords of Greece.[51] The growing Aetolian hostility to the Romans was expressed openly to one of the ten Roman commissioners at a meeting of Delphian Amphictyony in 196 BC.[52] This conflict would ultimately lead to the Aetolian War in 191 BC.

The Freedom of the Greeks

%252C_late_1st_century_BC%E2%80%93early_1st_century_AD%252C_Louvre_Museum_(7462828632).jpg.webp)

At the Isthmian Games of May 196 BC, Flamininus proclaimed the 'Freedom of the Greeks' met with general rejoicing of those who were attending the Games. The proclamation listed the free communities as follows: .[53] Nevertheless, the Romans kept garrisons in key strategic cities which had belonged to Macedon – Corinth, Chalcis and Demetrias – and the legions were not completely evacuated until 194 BC.

The extent of this grant of freedom was not entirely clear. Although Flamininus' proclamation had included a list of the communities formerly under Philip's control to which it applied,[54] the Romans quickly assumed (or were thrust into) the role of protector of Greek freedom more generally. The rhetoric of Greek freedom was almost immediately employed by the Romans and their allies to justify diplomatic and military action elsewhere, with the War against Nabis of Sparta, which was undertaken in 195 BC, ostensibly for the sake of the freedom of Argos.[55]

Seleucid conquest of Asia Minor

The initial background to the whole war had been the alliance of Antiochus III and Philip V against Ptolemy V and while the war had been raging in Greece, Antiochus III had completely defeated the Ptolemaic forces in Syria at the Battle of Panium. Since Philip had surrendered his claim to the communities in Asia Minor that had formerly been under Ptolemaic control, Antiochus III now advanced into Asia Minor to take them over for himself.[56] The conflicts arising from this would lead to the outbreak of the Roman–Seleucid War in 192 BC.

See also

- Military history of ancient Greece

- Agesimbrotus

References

- Didodorus XXVIII 5

- Livy 31.3

- Livy 31.14-16

- Livy 31.4-8

- Livy 31.12-14

- Polybius, Histories XVI 30–31; Livy 31.16-17

- He had been sent to Egypt to politely decline an offer by Ptolemy IV to send an army to protect Athens from Philip: Livy 31.9.

- Diodorus 28.6; Livy 31.16-17

- Livy 31.14, 22-3

- Diodoros 28.7; Livy 31.23-26

- Mikalson, Jon D. (1998). Religion in Hellenistic Athens. Berkeley/London: University of California Press., ch.6.

- Livy 31.28, 33

- Livy 31.27-32

- Livy 31.33-38

- Livy 31.39-40

- Livy 31.44-47

- Livy 31.41-43, 32.4-5

- Livy 32.1

- Livy 32.3

- Livy 32.5-6

- Livy 32.8, 27

- Livy 32.8

- Livy 32.9

- Diodorus XXVIII 11; Livy 32.10

- Livy 32.10-12

- Livy 32.13

- Livy 32.13-15

- Livy 32.18

- Livy 32.24

- Livy 32.16-17

- Livy 32.18-23

- Livy 32.23

- Livy 32.25

- Livy 32.32-37

- Polybios XVII.12

- Livy 32.38-40

- Livy 33.3-4

- Livy 32.28

- Livy 33.1-2, 33.21

- Livy 33.3

- Livy 33.5-11.

- Livy 33.14-15

- Livy 33.16-17

- Livy 33.17-18

- Livy 33.12-13

- Livy 33.19

- Livy 33.24-25. Others included Publius Cornelius Lentulus, Lucius Stertinius, Lucius Terentius Massaliota, Gnaeus Cornelius: Livy 33.35.

- Livy 33.30

- Livy 33.27-33

- Livy 33.12-13

- Livy 33.31

- Livy 33.35

- Livy 33.31-33

- The Corinthians, Phocians, Locrians, Euboeans, Magnesians, Thessalians, Perrhaebians, and the Phthiote Achaeans: Livy 33.32

- Livy 34.22

- Livy 33.34

Sources

Primary

- Polybius. The Histories. XVI.

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). XXVIII.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). XXXI–XXXIII.

- Plutarch Life of Flamininus

- Joannes Zonaras Extracts of History IX 15-17

Secondary

- Will, Edouard, L'histoire politique du monde hellénistique (Editions du Seuil, 2003 ed.), Tome II, pp. 121–178.

- Green, Peter, Alexander to Actium, the historical evolution of the Hellenistic Age, 1993, pp. 305–311.

- Kleu, Michael, Die Seepolitik Philipps V. von Makedonien, Bochum, Verlag Dr. Dieter Winkler, 2015.

| Library resources about Second Macedonian War |

Further reading

- Hammond, N. G. L.; Griffith, G. T.; Walbank, F. W. (1972). A History of Macedonia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sherwin-White, Adrian N. 1984. Roman foreign policy in the East 168 B.C. to A.D. 1. London: Duckworth.

- Gruen, Erich S (1984). The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome. Berkeley ; London: University of California Press.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230-170 B.C. Malden, MA. ; Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Dmitriev, Sviatoslav (2011). The Greek Slogan of Freedom and Early Roman Politics in Greece. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.