Sarus crane

The sarus crane (Antigone antigone) is a large nonmigratory crane found in parts of the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Australia. The tallest of the flying birds, standing at a height up to 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in), they are a conspicuous species of open wetlands in South Asia, seasonally flooded Dipterocarpus forests in Southeast Asia, and Eucalyptus-dominated woodlands and grasslands in Australia.[3]

| Sarus crane | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A. a. antigone from India with the distinct white "collar" | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Gruidae |

| Genus: | Antigone |

| Species: | A. antigone |

| Binomial name | |

| Antigone antigone | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

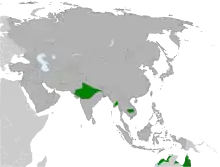

Approximate current global distribution

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The sarus crane is easily distinguished from other cranes in the region by its overall grey colour and the contrasting red head and upper neck. They forage on marshes and shallow wetlands for roots, tubers, insects, crustaceans, and small vertebrate prey. Like other cranes, they form long-lasting pair bonds and maintain territories within which they perform territorial and courtship displays that include loud trumpeting, leaps, and dance-like movements. In India, they are considered symbols of marital fidelity, believed to mate for life and pine the loss of their mates, even to the point of starving to death.

The main breeding season is during the rainy season, when the pair builds an enormous nest "island", a circular platform of reeds and grasses nearly 2 m in diameter and high enough to stay above the shallow water surrounding it. Increased agricultural intensity is often thought to have led to declines in sarus crane numbers, but they also benefit from wetland crops and the construction of canals and reservoirs. The stronghold of the species is in India, where it is traditionally revered and lives in agricultural lands in close proximity to humans. Elsewhere, the species has been extirpated in many parts of its former range.

Description

The adult sarus crane is very large, with grey wings and body, a bare red head and part of the upper neck; a greyish crown, and a long, greenish-grey, pointed bill. In flight, the long neck is held straight, unlike that of a heron, which folds it back, and the black wing tips can be seen; the crane's long, pink legs trail behind them. This bird has a grey ear covert patch, orange-red irises, and a greenish-grey bill. Juveniles have a yellowish base to the bill and the brown-grey head is fully feathered.[4]

| Measurements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| G. a. antigone[5] | |||

| Culmen | 172–182 mm (6.8–7.2 in) | ||

| Wing | 670–685 mm (26–27 in) | ||

| 625–645 mm (25–25 in) | |||

| Tail | 255–263 mm (10–10 in) | ||

| Tarsus | 310–355 mm (12–14 in) | ||

| Combined[6] | |||

| Culmen | 156–187 mm (6.1–7.4 in) | ||

| 155–169 mm (6.1–6.7 in) | |||

| Wing | 514–675 mm (20–27 in) | ||

| 557–671 mm (22–26 in) | |||

| Tail | 150–200 mm (5.9–7.9 in) | ||

| 100–200 mm (3.9–7.9 in) | |||

| Tarsus | 269–352 mm (11–14 in) | ||

| 272–350 mm (11–14 in) | |||

| Weight | 8.4 kg (19 lb) | ||

The bare red skin of the adult's head and neck is brighter during the breeding season. This skin is rough and covered by papillae, and a narrow area around and behind the head is covered by black, bristly feathers. The sexes do not differ in plumage, although males are on average larger than females; males of the Indian population can attain a maximum height around 180 cm (5.9 ft), making them the world's tallest extant flying bird. The weight of nominate race individuals is 6.8–7.8 kg (15–17 lb), while five adults of A. a. sharpii averaged 8.4 kg (19 lb). Across the distribution range, their weight can vary from 5 to 12 kg (11 to 26 lb), height typically from 115 to 167 cm (45 to 66 in), and wingspan from 220 to 250 cm (87 to 98 in).[6]

While individuals from northern populations are among the heaviest cranes, alongside the red-crowned and wattled cranes, and the largest in their range, birds from Australia tend to be smaller.[7] In Australia, the sarus can easily be mistaken for the more widespread brolga. The brolga has the red colouring confined to the head and not extending onto the neck.[6] Body mass in Australian sarus cranes was found to average 6.68 kg (14.7 lb) in males and 5.25 kg (11.6 lb) in females, with a range for both sexes of 5.0 to 6.9 kg (11.0 to 15.2 lb). Thus, Australian sarus cranes average about 25% lighter than the northern counterparts and are marginally lighter on average than brolgas.[8]

Distribution and habitat

The species has historically been widely distributed on the lowlands of India along the Gangetic plains, extending south to the Godavari River, west to coastal Gujarat, the Tharparkar District of Pakistan,[9] and east to West Bengal and Assam. The species no longer breeds in Punjab, though it winters regularly in the state.[10] Sarus cranes are rare in West Bengal and Assam,[11] and are no longer found in the state of Bihar. In Nepal, its distribution is restricted to the western and central lowland plains, with most of the population occurring in Rupandehi, Kapilvastu, and Nawalparasi districts.[12][13]

Two distinct populations of sarus cranes occur in Southeast Asia, the northern population in China and Myanmar, and the southern population in Cambodia and Vietnam.[3][14] The sarus used to extend to Thailand and further east into the Philippines, but may now be extinct in both these countries. In 2011, 24 captive-bred cranes raised from five founders were reintroduced into Thailand.[15] A reasonably sized population of over 150 cranes has recently been discovered breeding in rice fields in the Ayeyarwadi delta, Myanmar, with additional cranes confirmed in the states of Kachin, Shan, and Rakhine.[3] In Australia they are found only in the north-east, and are partly migratory in some areas.[16] The global range has shrunk and the largest occupied area, and the largest known population, is in India. Increasing paddy fields accompanied by an increase in the network of irrigation canals during and prior to the Green Revolution may have facilitated increases in the distribution and numbers of sarus cranes due to an increase in reliable moisture levels in various locations in India.[3][17][18] Although now found mainly at low elevations on the plains, some historical records exist from highland marshes further north in Harkit Sar and Kahag in Kashmir.[19] The sarus crane breeds in some high elevation regions such as near the Pong Dam in Himachal Pradesh, where populations may be growing in response to increasing rice cultivation along the reservoir.[12][13] In rice-dominated districts of Uttar Pradesh, sarus crane abundance (estimated as occupancy) was highest in the western districts, intermediate in the central districts, and minimal in the eastern districts. Sarus crane abundance was positively associated with percentage of wetlands on the landscape, and negatively with the percentage of area under rice cultivation.[20]

Until recently, little was known of sarus crane ecology from Australia. Breeding records (confirmed sightings of nests with eggs, or of adult birds with flightless young) were known from only three locations, all in the Gulf Plains in Queensland. Two records are from near Normanton town; one of adults with flightless chicks seen about 30 km west of the town[21] and another of adults incubating eggs seen 7-km south of the town.[22] The third record is a one-month study that provides details of 32 nests located within 10-km around Morr Morr cattle station in the Gilbert River floodplains.[23] A 3,000-km survey along the Gulf of Carpentaria located 141 territorial, breeding pairs spread out across the floodplains of the Mitchell, Gilbert, and Flinders Rivers.[24] Carefully mapping of breeding areas of sarus cranes in Australia is needed to understand their distribution range.[24][25] They are uncommon in Kakadu National Park, where the species is often hard to find among the more numerous brolgas.[25] Flocks in the non-breeding season are commonly seen in the Atherton Tablelands in eastern Queensland.[26]

In India, sarus cranes preferentially use wetlands[27] for nesting, but also nest in uncultivated patches amid flooded rice paddies (called khet-taavadi in Gujarat[28]), and in the rice paddies especially when wetlands are not available to breeding pairs.[27] Breeding pairs are territorial and prefer to forage in natural wetlands, though wetland crops such as rice and wheat are also frequented.[12][13][29] In south-western Uttar Pradesh, sarus cranes were found in wetlands of all sizes with larger numbers in larger wetlands.[30] In Australia, wintering, nonbreeding sarus cranes forage in areas with intensive agriculture (primarily maize, sugarcane, groundnuts) and smaller patches of cattle-grazing areas in the Atherton Tablelands in eastern Queensland.[26] They were observed to feed on grain, nuts, and insects from a range of crop fields, including stubble of maize and peanut crops, hay crops, fields with potato, legumes, and seed crops, and after harvest in fields of sugarcane, grass, and fodder crops.[31] Territorial, breeding sarus crane pairs in northern Queensland along the Gulf of Carpentaria use a range of habitats, but preferentially use low, open woodland on quaternary alluvial plains in outer river deltas and levees with a vegetation of Lysiphyllum cunninghamii, Eucalyptus microtheca, Corymbia confertiflora, Melaleuca spp., Excoecaria parvifolia, Atalaya hemiglauca, Grevillea striata, Eucalyptus leptophleba, C. polycarpa, C. confertiflora, and C. bella.[24]

Taxonomy and systematics

This species was described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae and placed it in the genus Ardea that included the larger herons.[32] Edward Blyth published a monograph on the cranes in 1881, in which he considered the "sarus crane" of India to be made up of two species, Grus collaris and Grus antigone.[33] Most modern authors recognize one species with three disjunct populations that are sometimes treated as subspecies, although the status of one extinct population from the Philippines is uncertain. The sarus cranes in India (referred to as A. a. antigone) are the largest, and in the east from Myanmar is replaced by a population that extends into Southeast Asia (referred to as A. a. sharpii). The sarus cranes from the Indian subcontinent are well marked and differentiated from the south-eastern population by having a white collar below the bare head and upper neck, and white tertiary remiges. The population in Australia (initially placed in A. a. sharpii (sometimes spelt sharpei, but amended to conform to the rules of Latin grammar[4]) was separated and named as the race A. a. gilliae, sometimes spelt gillae or even gilli), prior to a genetic analysis. A 2005 genetic analysis suggested that these three populations are representatives of a formerly continuous population that varied clinally.[7] The Australian subspecies was designated only in 1988, with the species itself first noticed in Australia in 1966 and regarded as a recent immigrant.[21] Native Australians, however, differentiated the sarus and the brolga and called the sarus "the crane that dips its head in blood". Sarus cranes of the Australian population are similar to those in Southeast Asia in having no white on the neck and tertiary remiges, but are distinguished by a larger grey patch of ear coverts. The Australian population shows the most recent divergence from the ancestral form with an estimated 3000 generations of breeding within Australia.[34] An additional subspecies, A. a. luzonica, was suggested for the population once found, but now extinct, in the Philippines. No distinctive characteristic is known of this population.[23]

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA, from a limited number of specimens, suggested that gene flow occurred within the continental Asian populations until the 20th-century reductions in range, and that Australia was colonized only in the Late Pleistocene, some 35,000 years ago.[34] This has been corroborated by nDNA microsatellite analyses on a large and widely distributed set of individuals in the sample.[7] This study further suggests that the Australian population shows low genetic variability. As there exists the possibility of (limited) hybridization with the genetically distinct brolga, the Australian sarus crane can be expected to be an incipient species.[7]

The sarus crane was formerly placed in the genus Grus, but a molecular phylogenetic study published in 2010 found that the genus, as then defined, was polyphyletic.[35] In the resulting rearrangement to create monophyletic genera, four species, including the sarus crane, were placed in the resurrected genus Antigone that had originally been erected by German naturalist Ludwig Reichenbach in 1853.[36][37]

Etymology

The common name sarus is from the Hindi name (sāras) for the species. The Hindi word is derived from the Sanskrit word sarasa for the "lake bird", (sometimes corrupted to sārhans).[12] While Indians held the species in veneration, British soldiers in colonial India hunted the bird, calling it the serious[38] or even cyrus.[39] The generic and specific names —after Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus, who hanged herself—may relate to the bare skin of the head and neck.[40]

Ecology and behaviour

Unlike many other cranes that make long migrations, sarus cranes are largely nonmigratory and few populations make relative short-distance migrations. In South Asia, four distinct population-level behaviours have been noted.[17] The first is the "wintering population" of a small number of sarus cranes that use wetlands in the state of Punjab during winters.[10] The source of this population is unclear, but is very likely to be from the growing population in Himachal Pradesh. The second is the "expanding population" consisting of cranes appearing in new areas following new irrigation structures in semiarid and arid areas primarily in Gujarat and Rajasthan. The third is the "seasonally migratory" population, also primarily in the arid zone of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Cranes from this population aggregate in remaining wetlands and reservoirs during the dry summer, and breeding pairs set up territories during the rainy season (July – October) remaining on territories throughout the winter (November – March). The fourth population is "perennially resident" and found in areas such as southwestern Uttar Pradesh, where artificial and natural water sources enable cranes to stay in the same location throughout the year. Migratory populations are also known from Southeast Asia and Australia.[14][26] In Southeast Asia, cranes congregate in few remnant wetlands during the dry season. In Australia, flocks aggregate on the Atherton Highlands, where agriculture is conducive for sarus cranes.

- Pair behaviour

Bowing display

Bowing display

Leap

Leap Unison calling

Unison calling

Breeding pairs maintain territories that are defended from other cranes using a large repertoire of calls and displays. In Uttar Pradesh, less than a tenth of the breeding pairs maintain territories at wetlands while the rest of the pairs are scattered in smaller wetlands and agricultural fields.[27][41] Non-breeding birds form flocks that vary from 1–430 birds.[12][42][43] In semi-arid areas, breeding pairs and successfully fledged juveniles depart from territories in the dry season and join non-breeding flocks. In areas with perennial water supply, as in the western plains of Uttar Pradesh, breeding pairs maintain perennial territories.[27] The largest known flocks are from the 29-km2 Keoladeo National Park[44] – with as many as 430 birds, and from unprotected, community-owned wetlands in Etawah, Mainpuri, Etah and Kasganj districts in Uttar Pradesh, ranging from 245 to 412 birds.[12] Flocks of over 100 birds are also reported from Gujarat in India[45] and Australia.[26] Sarus crane populations in Keoladeo National Park have been noted to drop from over 400 birds in summer to just 20 birds during the monsoon.[44] In areas with perennial wetlands on the landscape, such as in western Uttar Pradesh, numbers of nonbreeding sarus cranes in flocks can be relatively stable throughout the year. In Etawah, Mainpuri, Etah, and Kasganj districts, nonbreeding sarus cranes form up to 65% of the regional population.[46] Breeding pairs in Australia similarly defend territories from neighbouring crane pairs, and nonbreeding birds are found in flocks frequently mixed with brolgas.[24] In their breeding grounds in north-eastern Australia, nonbreeding sarus cranes constitute less than 25% of the population in some years.

They roost in shallow water, where they may be safe from some ground predators.[6] Adult birds do not moult their feathers annually, but feathers are replaced about once every two to three years.[47]

Feeding

Sarus cranes forage in shallow water (usually with less than 30 cm (0.98 ft) depth of water) or in fields, frequently probing in mud with their long bills. In the dry season (after breeding), sarus cranes in Anlung Pring Sarus Crane Conservation Area, Cambodia, used wetlands with 8–10 cm of water.[48] They are omnivorous, eating insects (especially grasshoppers), aquatic plants, fish (perhaps only in captivity[49]), frogs, crustaceans, and seeds.[12] Occasionally tackling larger vertebrate prey such as water snakes (Fowlea piscator),[6] sarus cranes may in rare cases feed on the eggs of birds[50] and turtles.[51] Plant matter eaten includes tubers, corms of aquatic plants, grass shoots as well as seeds and grains from cultivated crops such as groundnuts and cereal crops such as rice.[6] In the dry season, cranes flocking in Southeast Asian wetlands are in areas with an abundance of Eleocharis dulcis and E. spiralis, both of which produce tubers on which the cranes are known to feed.[48] In their breeding grounds in north-eastern Australia, isotopic analyses on molted feathers revealed sarus crane diets to comprise a great diversity of vegetation, and restricted to a narrow range of trophic levels.[24]

Courtship and breeding

Sarus cranes have loud, trumpeting calls, which as in other cranes, are produced by the elongated trachea that forms coils within the sternal region.[52] Pairs may indulge in spectacular displays of calling in unison and posturing. These include "dancing" movements that are performed both during and outside the breeding season and involve a short series of jumping and bowing movements made as one of the pair circles around the other.[53] Dancing may also be a displacement activity, when the nest or young is threatened.[6] The cranes breed mainly during the monsoons in India (from July to October, although a second brood may occur),[44] and breeding has been recorded in all the months.[12] They build large nests, platforms made of reeds and vegetation in wet marshes or paddy fields.[28] The nest is constructed within shallow water by piling up rushes, straw, grasses with their roots, and mud so that the platform rises above the level of the water to form a little island. The nest is unconcealed and conspicuous, being visible from afar, and defended fiercely by the pair.[54]

Data collated over a century from South Asia show sarus cranes nesting throughout the year.[12] More focused observations, however, show nesting patterns to be closely tied to rainfall patterns.[27][28] An exception to this rule was the unseasonal nesting observed in the artificially flooded Keoladeo-Ghana National Park,[44] and in marshes created by irrigation canals in Kota district of Rajasthan, India.[55] Based on these observations, unseasonal nesting (or nesting outside of the monsoon) of sarus cranes was thought to be due to either the presence of two populations, some pairs raising a second brood, and unsuccessful breeding by some pairs in the normal monsoon season, prompting them to nest again when conditions such as flooded marshes remain. A comprehensive assessment of unseasonal nesting based on collation of over 5,000 breeding records, however, showed that unseasonal nesting by sarus cranes in South Asia was very rare and was only carried out by pairs that did not succeed in raising chicks in the normal nesting season.[18] Unseasonal nests were initiated in years when rainfall extended beyond the normal June–October period, and when rainfall volume was higher than normal; or when artificial wet habitats were created by man-made structures such as reservoirs and irrigation canals to enhance crop production.[18] Nest initiation in northern Queensland is also closely tied to rainfall patterns, with most nests being initiated immediately after the first major rains.[24]

The nests can be more than 2 m (6 ft) in diameter and nearly 1 m (3 ft) high.[56] Pairs show high fidelity to the nest site, often refurbishing and reusing a nest for as many as five breeding seasons.[57] The clutch is one or two eggs (rarely three[27][58] or four[59]) which are incubated by both sexes[59] for about 31 days (range 26–35 days[27][60]). Eggs are chalky white and weigh about 240 grams.[6] When disturbed from the nest, parents may sometimes attempt to conceal the eggs by attempting to cover them with material from the edge of the nest.[61] The eggshells are removed by the parents after the chicks hatch either by carrying away the fragments or by swallowing them.[62] About 30% of all breeding pairs succeed in raising chicks in any year, and most of the successful pairs raise one or two chicks each, with brood sizes of three being rare.[63][64] One survey in Australia found 60% of breeding pairs to have successfully fledged chicks.[24] This high success rate is attributed to above-normal rainfall that year. The chicks are fed by the parents for the first few days, but are able to feed independently after that, and follow their parents for food.[65] When alarmed, the parent cranes use a low korr-rr call that signals chicks to freeze and lie still.[66] Young birds stay with their parents until the subsequent breeding season.[27] In captivity, birds breed only after their fifth year.[6] The sarus crane is widely believed to pair for life, but cases of "divorce" and mate replacement have been recorded.[67]

Mortality factors

Eggs are often destroyed at the nest by jungle (Corvus macrorhynchos) and house crows (C. splendens) in India.[62] In Australia, suspected predators of young birds include the dingo (Canis dingo) and fox (Vulpes vulpes), while brahminy kites (Haliastur indus) have been known to take eggs.[6] Removal of eggs by farmers (to reduce crop damage) or children (in play),[27] or by migrant labourers for food[55] or opportunistic egg collection during trips to collect forest resources[68] are prominent causes of egg mortality. Between 31 and 100% of nests with eggs can fail to hatch eggs for these reasons. Chicks are also prone to predation (estimated at about 8%) and collection at the nest, but more than 30% die of unknown reasons.[27][68][69][70]

Breeding success (percentage of eggs hatching and surviving to fledging stage) has been estimated to be about 20% in Gujarat[71] and 51–58% in south-western Uttar Pradesh.[27] In areas where farmers are tolerant, nests in flooded rice fields and those in wetlands have similar rates of survival.[27] Pairs that nest later in the season have a lower chance of raising chicks successfully, but this improves when territories have more wetlands.[27] Nest success (percentage of nests in which at least one egg hatched) for 96 sarus nests that were protected by locals during 2009–2011 via a payment-for-conservation program was 87%.[68] More pairs are able to raise chicks in years with higher total rainfall, and when territory quality was undisturbed due to increased farming or development. Permanent removal of pairs from the population due to developmental activities caused reduced population viability, and was a far more important factor impacting breeding success relative to total annual rainfall.[64]

Breeding success in Australia has been estimated by counting the proportion of young-of-the-year in wintering flocks in the crop fields of Atherton Tablelands in north-eastern Queensland.[26] Young birds constituted 5.32% to 7.36% of the wintering population between 1997 and 2002. It is not known if this variation represents annual differences in conditions in the breeding areas or if it included biases such as different proportions of breeding pairs traveling to Atherton to over-winter. It is also not known how these proportions equate to more standard metrics of breeding success such as proportions of breeding pairs succeeding in raising young birds. One multi-floodplain survey in Australia found 60% of all breeding pairs to have raised at least one chick, with 34% of successful pairs fledging two chicks each.[24] Breeding success, and proportions of pairs that raised two chicks each, was similar in each floodplain.

Little is known about the diseases and parasites of the sarus crane, and their effects on wild bird populations. A study conducted at the Rome zoo noted that these birds were resistant to anthrax.[72] Endoparasites that have been described include a trematode, Opisthorhis dendriticus from the liver of a captive crane at the London zoo[73] and a Cyclocoelid (Allopyge antigones) from an Australian bird.[74] Like most birds, they have bird lice and the species recorded include Heleonomus laveryi and Esthiopterum indicum.[75]

In captivity, sarus cranes have been known to live for as long as 42 years.[note 1][76][77] Premature adult mortality is often the result of human actions. Accidental poisoning by monocrotophos, chlorpyrifos and dieldrin-treated seeds used in agricultural areas has been noted.[78][79][80] Adults have been known to fly into power lines and die of electrocution, this is responsible for killing about 1% of the local population each year.[81]

Conservation status

.jpg.webp)

An estimated 15–20,000 mature sarus cranes were left in the wild in 2009.[1] The Indian population is less than 10,000, but of the three subspecies, is the healthiest in terms of numbers. They are considered sacred and the birds are traditionally left unharmed,[55] and in many areas, they are unafraid of humans. They used to be found on occasion in Pakistan, but have not been seen there since the late 1980s. The population in India has, however, declined.[1] Estimates of the global population suggest that the population in 2000 was at best about 10% and at the worst just 2.5% of the numbers that existed in 1850.[82] Many farmers in India believe that these cranes damage standing crops,[13] particularly rice, although studies show that direct feeding on rice grains resulted in losses amounting to less than 1% and trampling could account for grain loss around 0.4–15 kilograms (0.88–33.07 lb).[83] The attitude of farmers tends to be positive in spite of these damages, and this has helped in conserving the species within agricultural areas.[64][84] The role of rice paddies and associated irrigation structures may be particularly important for the birds' conservation, since natural wetlands are increasingly threatened by human activity.[3][17][27] The conversion of wetlands to farmland, and farmland to more urban uses are major causes for habitat loss and long-term population decline.[64] Compensating farmers for crop losses has been suggested as a measure that may help, but needs to be implemented judiciously so as not to corrupt and remove existing local traditions of tolerance.[3][69] Farmers in sarus crane wintering areas in Australia are beginning to use efficient methods to harvest crops, which may lead to lowered food availability. Farmers are also transitioning from field crops to perennial and tree crops that have higher returns. This may reduce available foraging habitat for cranes, and may increase conflict with farmers in the remaining, few crop fields.[31]

A review of literature and assessment of abundance of sarus cranes in Nepal suggests that past field methods were either inadequate or incomplete to properly estimate abundances, and that the population of cranes in Nepal may be on the increase.[85] The Australian population is greater than 5,000 birds and may be increasing,[7] however, the Southeast Asian population has been decimated by war and habitat change (such as intensive agriculture, deforestation, and draining of wetlands), and by the mid-20th century, had disappeared from large parts of its range which once stretched north to southern China. Some 1500–2000 birds are left in several fragmented subpopulations, though recent surveys in Myanmar have discovered previously unknown breeding populations in several locations.[3]

Payment to locals to guard nests and help increase breeding success has been attempted in northern Cambodia. Nest success of protected nests was significantly higher than that of unprotected nests, and positive population-level impacts were apparent.[68] However, the program also caused local jealousies leading to deliberate disturbance of nests, and did nothing to alleviate larger-scale and more permanent threats due to habitat losses leading to the conclusion that such payment-for-conservation programs are at best a short-term complement, and not a substitute, to more permanent interventions that include habitat preservation.[68] The little-known Philippine population became extinct in the late-[86] 1960s.[1]

The sarus crane is classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.[1] Threats include habitat destruction and/or degradation, hunting and collecting, and environmental pollution, and possibly diseases or competing species. The effects of inbreeding in the Australian population, once thought to be a significant threat due to hybridization with brolgas producing hybrid birds called "sarolgas", is now confirmed to be minimal, suggesting that it is not a major threat.[3] New plans for developing the floodplain areas of northern Queensland may have detrimental impacts on breeding sarus crane populations, and require to incorporate the needs of cranes via conservation of a diversity of habitats that are currently found in the region.[24]

The species has been extirpated in Malaysia and the Philippines. Reintroduction programs in Thailand have made use of birds from Cambodia. As of 2019, attempts to reintroduce the birds to eastern Thailand have shown some promise.[87]

In culture

The species is venerated in India and legend has it that the poet Valmiki cursed a hunter for killing a sarus crane and was then inspired to write the epic Ramayana.[88][89] The species was a close contender to the Indian peafowl as the national bird of India.[29] Among the Gondi people, the tribes classified as "five-god worshippers" consider the sarus crane as sacred.[90] The meat of the sarus was considered taboo in ancient Hindu scriptures.[91] The sarus crane is widely thought to pair for life and that death of one partner leads to the other pining to death.[92] They are a symbol of marital virtue and in parts of Gujarat, taking a newlywed couple to see a pair of sarus cranes is customary.[12]

Although venerated and protected by Indians, these birds were hunted during the colonial period. Killing a bird would lead to its surviving partner trumpeting for many days, and the other was traditionally believed to starve to death. Even sport-hunting guides discouraged shooting these birds.[93] According to 19th-century British zoologist Thomas C. Jerdon, young birds were good to eat, while older ones were "worthless for the table".[94] Eggs of the sarus crane are, however, used in folk remedies in some parts of India.[12][95]

Young birds were often captured and kept in menageries, both in India and in Europe in former times. They were also successfully bred in captivity early in the 17th century by Emperor Jehangir,[96] who also noted that the eggs were laid with an interval of two days and that incubation period was 34 days.[6] They were also bred in zoos in Europe and the United States in the early 1930s.[56][97]

The young birds are easily reared by hand, and become very tame and attached to the person who feeds them, following him like a dog. They are very amusing birds, going through the most grotesque dances and antics, and are well worth keeping in captivity. One which I kept, when bread and milk was given to him, would take the bread out of the milk, and wash it in his pan of water before eating it. This bird, which was taken out of the King's palace at Lucknow, was very fierce towards strangers and dogs, especially if they were afraid of him. He was very noisy—the only bad habit he possessed

The Indian state of Uttar Pradesh has declared the sarus crane as its official state bird.[99] An Indian 14-seater propeller aircraft, the Saras, is named after this crane.[100][101]

Notes

- Flower (1938) notes only 26 years in captivity

References

- BirdLife International. 2016. Antigone antigone. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22692064A93335364.en. Downloaded on 23 April 2020.

- Blanford, W.T (1896). "A note on the two sarus cranes of the Indian region". Ibis. 2: 135–136. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1896.tb06980.x.

- Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2019). "Species review: Sarus Crane (Grus antigone)". In Mirande, Claire M.; Harris, James T. (eds.). Crane Conservation Strategy. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, USA. pp. 323–345.

- Rasmussen, PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. pp. 138–139.

- Ali, S & S. D. Ripley (1980). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 2 (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 141–144.

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (1983). Cranes of the world. Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. ISBN 978-0-253-11255-2.

- Jones, Kenneth L.; Barzen, Jeb A.; Ashley, Mary V. (2005). "Geographical partitioning of microsatellite variation in the sarus crane". Animal Conservation. 8 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1017/S1367943004001842.

- Dunning Jr.; John B., eds. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781420064445.

- Azam, Mirza Mohammad & Chaudhry M. Shafique (2005). "Birdlife in Nagarparkar, district Tharparkar, Sindh". Rec. Zool. Surv. Pakistan. 16: 26–32.

- Bal, R.; Dua, A. (2010). "Cranes in unlisted wetlands of north-west Punjab". Birding Asia. 14: 103–106.

- Choudhury, A. (1998). "Mammals, birds and reptiles of Dibru-Saikhowa Sanctuary, Assam, India". Oryx. 32 (3): 192–200. doi:10.1017/S0030605300029951.

- Sundar, KSG; Choudhury, BC (2003). "The Indian Sarus Crane Grus a. antigone: a literature review". Journal of Ecological Society. 16: 16–41.

- Sundar, K.S.G.; Kaur, J.; Choudhury, BC (2000). "Distribution, demography and conservation status of the Indian Sarus Crane (Grus a. antigone) in India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 97 (3): 319–339.

- Archibald, G.W.; Sundar, KSG; Barzen, J. (2003). "A review of the three subspecies of Sarus Cranes Grus antigone". Journal of Ecological Society. 16: 5–15.

- Insee, Jiranan; Kamolnorranath, Sumate; Baicharoen, Sudarat; Chumpadang, Sriphapai; Sawasu, Wanchai; Wajjwalku, Worawidh (2014). "PCR-based Method for Sex Identification of Eastern Sarus Crane (Grus antigone sharpii): Implications for Reintroduction Programs in Thailand". Zoological Science. 31 (2): 95–100. doi:10.2108/zsj.31.95. PMID 24521319. S2CID 36566462.

- Marchant, S.; Higgins, P.J. (1993). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic birds. Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2018). "Case study. Sarus Cranes and Indian farmers: an ancient coexistence". In Austin, Jane E.; Morrison, Kerryn; Harris, James T. (eds.). Cranes and Agriculture: A Global Guide for Sharing the Landscape. https://www.savingcranes.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/cranes_and_agriculture_web_2018.pdf: International Crane Foundation. pp. 206–210.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sundar, K.S. Gopi; Yaseen, Mohammed; Kathju, Kandarp (2018). "The role of artificial habitats and rainfall patterns in the unseasonal nesting of Sarus Cranes (Antigone antigone) in South Asia". Waterbirds. 41 (1): 81–86. doi:10.1675/063.041.0111. S2CID 89705278.

- Vigne, GT (1842). Travels in Kashmir, Ladak, Iskardo. Vol. 2. Henry Colburn, London.

- Sundar, K.S.G.; Kittur, S. (2012). "Methodological, temporal and spatial factors affecting modeled occupancy of resident birds in the perennially cultivated landscape of Uttar Pradesh, India". Landscape Ecology. 27: 59–71. doi:10.1007/s10980-011-9666-3. S2CID 15212012.

- Gill, H.B. (1967). "First record of the Sarus Crane in Australia". The Emu. 69: 48–52.

- Walkinshaw, L.H. (1973). Cranes of the world. New York: Winchester Press.

- Meine, Curt D.; Archibald, George W., eds. (1996). The cranes: Status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, U.K. p. 126. ISBN 978-2-8317-0326-8.

- Sundar, K. S. Gopi; Grant, John, D.A.; Veltheim, Inka; Kittur, Swati; Brandis, Kate; McCarthy, Michael A.; Scambler, Elinor (2019). "Sympatric cranes in northern Australia: abundance, breeding success, habitat preference and diet". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 119: 79–89. doi:10.1080/01584197.2018.1537673. S2CID 133977233.

- Beruldsen, G.R. (1997). "Is the Sarus Crane under threat in Australia?". Sunbird: Journal of the Queensland Ornithological Society. 27 (3): 72–78.

- Grant, John (2005). "Recruitment rates of Sarus Crane (Grus antigone) in northern Queensland". The Emu. 105 (4): 311–315. doi:10.1071/mu05056. S2CID 85187485.

- Sundar, K.S.G. (2009). "Are rice paddies suboptimal breeding habitat for Sarus Cranes in Uttar Pradesh, India?". The Condor. 111 (4): 611–623. doi:10.1525/cond.2009.080032. S2CID 198153258.

- Borad, C.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Parasharya, B.M. (2001). "Nest site selection by the Indian sarus crane in the paddy crop agrosystem". Biological Conservation. 98 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(00)00145-2.

- Sundar, KSG; Choudhury, BC (2006). "Conservation of the Sarus Crane Grus antigone in Uttar Pradesh, India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 103 (2–3): 182–190.

- Sundar, K.S.G.; Kittur, S. (2013). "Can wetlands maintained for human use also help conserve biodiversity? Landscape-scale patterns of bird use of wetlands in an agriculture landscape in north India". Biological Conservation. 168 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.09.016.

- Nevard, Timothy D.; Leiper, Ian; Archibald, George; Garnett, Stephen T. (2018). "Farming and cranes on the Atherton Tablelands, Australia". Pacific Conservation Biology. online first (2): 184. doi:10.1071/PC18055.

- Gmelin, JF (1788). Systema Naturae. 1 (13th ed.). Lipsiae: impensis Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 622.

- Blyth, Edward (1881). The natural history of the cranes. R H Porter. pp. 45–51.

- Wood, T.C. & Krajewsky, C (1996). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation among the subspecies of Sarus Crane (Grus antigone)" (PDF). The Auk. 113 (3): 655–663. doi:10.2307/4088986. JSTOR 4088986.

- Krajewski, C.; Sipiorski, J.T.; Anderson, F.E. (2010). "Mitochondrial genome sequences and the phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae)". Auk. 127 (2): 440–452. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09045. S2CID 85412892.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Flufftails, finfoots, rails, trumpeters, cranes, limpkin". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Reichenbach, Ludwig (1853). Handbuch der speciellen Ornithologie. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister. p. xxiii.

- Yule, Henry (1903). etymological, historical; geographical; discursive. New; William Crooke, B.A. (eds.). Hobson-Jobson: A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms. J. Murray, London. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Stocqueler, JH (1848). The Oriental Interpreter. C. Cox, London.

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (1983). Cranes of the world. Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-253-11255-2.

- Sundar, K.S.G. (2005). "Effectiveness of road transects and wetland visits for surveying Black-necked Storks Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus and Sarus Cranes Grus antigone in India". Forktail. 21: 27–32.

- Livesey, TR (1937). "Sarus flocks". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 39 (2): 420–421.

- Prasad, SN; NK Ramachandran; HS Das & DF Singh (1993). "Sarus congregation in Uttar Pradesh". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 33 (4): 68.

- Ramachandran, N.K.; Vijayan, V.S. (1994). "Distribution and general ecology of the Sarus Crane (Grus antigone) in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 91 (2): 211–223.

- Acharya, Hari Narayan G (1936). "Sarus flocks". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 38 (4): 831.

- Sundar, K.S.G. (2005). "Effectiveness of road transects and wetland visits for surveying Black-necked Storks Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus and Sarus Cranes Grus antigone in India" (PDF). Forktail. 21: 27–32.

- Hartert, Ernst & F Young (1928). "Some observations on a pair of Sarus Cranes at Tring". Novitates Zoologicae. 34: 75–76.

- Yav, Net; Parrott, Marissa; Seng, Kimhout; Zalinge, Robert van (2015). "Foraging preferences of eastern Sarus Crane Antigone antigone sharpii in Cambodia". Cambodian Journal of Natural History. 2015: 165.171.

- Law, SC (1930). "Fish-eating habit of the Sarus Crane (Antigone antigone)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 34 (2): 582–583.

- Sundar, K.S.G. (2000). "Eggs in the diet of the Sarus Crane Grus antigone (Linn.)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 97 (3): 428–429.

- Chauhan, R; Andrews, Harry (2006). "Black-necked Stork Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus and Sarus Crane Grus antigone depredating eggs of the three-striped roofed turtle Kachuga dhongoka" (PDF). Forktail. 22: 174–175.

- Fitch, WT (1999). "Acoustic exaggeration of size in birds via tracheal elongation: comparative and theoretical analyses" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 248: 31–48. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01020.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011.

- Mukherjee, A (2002). "Observations on the mating behaviour of the Indian Sarus Crane Grus antigone in the wild". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 99 (1): 108–113.

- Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook of Indian Birds (4th ed.). Gurney and Jackson, London. pp. 446–447.

- Kaur, J.; Choudhury, B.C.; Choudhury, B.C. (2008). "Conservation of the vulnerable Sarus Crane Grus antigone antigone in Kota, Rajasthan, India: a case study of community involvement". Oryx. 42 (3): 452–455. doi:10.1017/S0030605308000215.

- Walkinshaw, Lawrence H. (1947). "Some nesting records of the sarus crane in North American zoological parks" (PDF). The Auk. 64 (4): 602–615. doi:10.2307/4080719. JSTOR 4080719.

- Mukherjee, A; Soni, V.C.; Parasharya, C.K. Borad B.M. (December 2000). "Nest and eggs of Sarus Crane (Grus antigone antigone Linn.)". Zoos' Print Journal. 15 (12): 375–385. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.15.12.375-85.

- Handschuh, Markus; Vann Rours & Hugo Rainey (2010). "Clutch size of sarus crane Grus antigone in the Northern Plains of Cambodia and incidence of clutches with three eggs" (PDF). Cambodian Journal of Natural History. 2: 103–105.

- Sundar, KSG & Choudhury, BC (2005). "Effect of incubating adult sex and clutch size on egg orientation in Sarus Cranes Grus antigone" (PDF). Forktail. 21: 179–181. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2008.

- Ricklefs RE; Bruning, DF & Archibald, G W (1986). "Growth rates of cranes reared in captivity" (PDF). The Auk. 103 (1): 125–134. doi:10.1093/auk/103.1.125. JSTOR 4086970.

- Kathju, K (2007). "Observations of unusual clutch size, renesting and egg concealment by Sarus Cranes Grus antigone in Gujarat, India" (PDF). Forktail. 23: 165–167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2012.

- Sundar, K.S.G.; Choudhury, B.C. (2003). "Nest sanitation in Sarus Cranes Grus antigone in Uttar Pradesh, India" (PDF). Forktail. 19: 144–146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2008.

- Sundar, KSG (2006). "Instances of successful raising of three chicks by Sarus Crane Grus antigone pairs" (PDF). Forktail. 22: 124–125.

- Sundar, K.S.G. (2011). "Agricultural intensification, rainfall patterns, and breeding success of large waterbirds breeding success in the extensively cultivated landscape of Uttar Pradesh, India". Biological Conservation. 144 (12): 3055–3063. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.012.

- Lahiri, R.K. (1955). "Breeding of the sarus crane [Antigone a. antigone (Linn.)] in captivity". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 53: 130–131.

- Ali, S (1957). "Notes on the Sarus Crane". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 55 (1): 166–168.

- Sundar, K.S.G. (2005). "Observations of mate change and other aspects of pair-bond in the Sarus Crane Grus antigone". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 102 (1): 109–112.

- Clements, T.; Rainey, H.; An, D.; Rours, V.; Tan, S.; Thong, S.; Sutherland, W. J. & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2012). "An evaluation of the effectiveness of a direct payment for biodiversity conservation: The Bird Nest Protection Program in the Northern plains of Cambodia". Biological Conservation. 157: 50–59. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.020.

- Mukherjee, A; C. K. Borad & B. M. Parasharya (2002). "Breeding performance of the Indian sarus crane in the agricultural landscape of western India". Biological Conservation. 105 (2): 263–269. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00186-0.

- Kaur J & Choudhury, BC (2005). "Predation by Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus on chick of Sarus Crane Grus antigone antigone in Kota, Rajasthan". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 102 (1): 102.

- Borad, CK; Mukherjee, Aeshita; Parasharya, BM & S.B. Patel (2002). "Breeding performance of Indian Sarus Crane Grus antigone antigone in the paddy crop agroecosystem". Biodiversity and Conservation. 11 (5): 795–805. doi:10.1023/A:1015367406200. S2CID 34566439.

- Ambrosioni P, Cremisini ZE (1948). "Epizoozia de carbonchi ematico negli animali del giardino zoologico di Roma". Clin. Vet. (in Italian). 71: 143–151.

- Lal, Makund Behari (1939). "Studies in Helminthology-Trematode parasites of birds". Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section B. 10 (2): 111–200.

- Johnston, SJ (1913). "On some Queensland trematodes, with anatomical observations and descriptions of new species and genera" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 59: 361–400.

- Tandan, BK (2009). "The genus Esthiopterum (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera)" (PDF). Journal of Entomology Series B, Taxonomy. 42 (1): 85–101. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.1973.tb00059.x.

- Flower, M.S.S. (1938). "The duration of life in animals – IV. Birds: special notes by orders and families". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 195–235.

- Ricklefs, R. E. (2000). "Intrinsic aging-related mortality in birds" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 31 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048X.2000.210201.x.

- Pain, D.J.; Gargi, R.; Cunningham, A.A.; Jones, A.; Prakash, V. (2004). "Mortality of globally threatened Sarus cranes Grus antigone from monocrotophos poisoning in India". Science of the Total Environment. 326 (1–3): 55–61. Bibcode:2004ScTEn.326...55P. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.12.004. PMID 15142765.

- Muralidharan, S. (1993). "Aldrin poisoning of Sarus cranes (Grus antigone) and a few granivorous birds in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, India". Ecotoxicology. 2 (3): 196–202. doi:10.1007/BF00116424. PMID 24201581. S2CID 29477173.

- Rana, Gargi; Prakash, Vibhu (2004). "Unusually high mortality of cranes in areas adjoining Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 101 (2): 317.

- Sundar, KSG & BC Choudhury (2005). "Mortality of sarus cranes (Grus antigone) due to electricity wires in Uttar Pradesh, India". Environmental Conservation. 32 (3): 260–269. doi:10.1017/S0376892905002341.

- BirdLife International (2001). Threatened birds of Asia: the BirdLife International Red Data Book (PDF). BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK. ISBN 978-0-946888-42-9.

- Borad, C.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Parasharya, B.M. (2001). "Damage potential of Indian sarus crane in paddy crop agroecosystem in Kheda district Gujarat, India". Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 86 (2): 211–215. doi:10.1016/S0167-8809(00)00275-9.

- Donald, C.H. (1922). In nature's garden. London: John Lane. pp. 199–208.

- Katuwal, Hem Bahadur (2016). "Sarus cranes in lowlands of Nepal: Is it declining really?". Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity. 9 (3): 259–262. doi:10.1016/j.japb.2016.06.003.

- Hutasingh, Onnucha (14 September 2019). "Thai cranes make comeback". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Hutasingh, Onnucha (14 September 2019). "Thai cranes make a comeback". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Leslie, J. (October 1998). "A bird bereaved: The identity and significance of Valmiki's kraunca". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 26 (5): 455–487. doi:10.1023/A:1004335910775. JSTOR 23496373. S2CID 169152694.

- Hammer, Niels (April 2009). "Why Sārus Cranes epitomize Karuṇarasa in the Rāmāyaṇa". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. (Third Series). 19 (2): 187–211. doi:10.1017/S1356186308009334. JSTOR 27756045.

- Russell, R. V. (1916). The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. Vol. 3. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 66. LCCN 16011742.

- The Sacred Laws of the Aryas. Parts 1 and 2. Translated by Bühler, Georg. New York: The Christian Literature Company. 1898. p. 64. LCCN 32034301.

- Kipling, John Lockwood (1904). Beast and Man in India. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 37.

- Finn, Frank (1915). Indian sporting birds. London: Francis Edwards. pp. 117–120.

- Jerdon, T. C. (1864). Birds of India. 3. Calcutta: George Wyman & Co.

- Kaur, J. & Choudhury, B. C. (2003). "Stealing of Sarus crane eggs" (PDF). Current Science. 85 (11): 1515–1516.

- Ali, S (1927). "The Moghul emperors of India as naturalists and sportsmen. Part 2". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 32 (1): 34–63.

- Rothschild, D. (1930). "Sarus crane breeding at Tring". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 50: 57–68.

- Irby, L. H. (1861). "Notes on birds observed in Oudh and Kumaon". Ibis. 3 (2): 217–251. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1861.tb07456.x.

- "States and Union Territories Symbols". Government of India. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- Norris, Guy (2005). "India works to overcome Saras design glitches". Flight International. 168 (5006): 28.

- Mishra, Bibhu Ranjan (16 November 2009). "After IAF, Indian Posts shows interest for NAL Saras". Business Standard. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

Other sources

- Matthiessen, Peter & Bateman, Robert (2001). The Birds of Heaven: Travels with Cranes. North Point Press, New York. ISBN 0-374-19944-2

- Weitzman, Martin L. (1993). "What to preserve? An application of diversity theory to crane conservation". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 108 (1): 157–183. doi:10.2307/2118499. ISSN 0033-5533. JSTOR 2118499.

- Haigh, J. C. & Holt, P. E. (1976). "The use of the anaesthetic "CT1341" in a Sarus crane". Can Vet J. 17 (11): 291–292. PMC 1697384. PMID 974983.

- Duan, W. & Fuerst, P. A. (2001). "Isolation of a sex-Linked DNA sequence in cranes". Journal of Heredity. 92 (5): 392–397. doi:10.1093/jhered/92.5.392. PMID 11773245.

- Menon, G. K.; R. V. Shah & M. B. Jani (1980). "Observations on integumentary modifications and feathering on head and neck of the Sarus Crane, Grus antigone antigone". Pavo. 18: 10–16.

- Sundar, K. S. G. (2006). "Flock size, density and habitat selection of four large waterbirds species in an agricultural landscape in Uttar Pradesh, India: implications for management". Waterbirds. 29 (3): 365–374. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[365:fsdahs]2.0.co;2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grus antigone. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Grus antigone. |

- International Crane Foundation: Sarus Crane, Grus antigone. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center: The Cranes Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan: Sarus Crane (Grus antigone). Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Sarus Crane (International Crane Foundation)

- International Crane Foundation (literature)

- Sarus Crane (Grus antigone) from Cranes of the World (1983) by Paul Johnsgard

- Arkive

_feeding_juvenile_Lumbini.jpg.webp)