Safrole

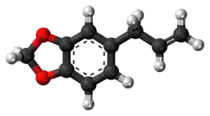

Safrole is an organic compound with the formula CH2O2C6H3CH2CH=CH2. It is a colorless oily liquid, although impure samples can appear yellow. A member of the phenylpropanoid family of natural products, it is found in sassafras plants, among others. Small amounts are found in a wide variety of plants, where it functions as a natural antifeedant.[2] Ocotea pretiosa,[3] which grows in Brazil, and Sassafras albidum,[2] which grows in eastern North America, are the main natural sources of safrole. It has a characteristic "sweet-shop" aroma.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

5-(Prop-2-en-1-yl)-2H-1,3-benzodioxole | |

| Other names

5-(2-Propenyl)-1,3-benzodioxole 5-Allylbenzo[d][1,3]dioxole 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.133 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 3082 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H10O2 | |

| Molar mass | 162.188 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.096 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 11 °C (52 °F; 284 K) |

| Boiling point | 232 to 234 °C (450 to 453 °F; 505 to 507 K) |

| −97.5×10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |   |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| H302, H341, H350 | |

| P201, P281, P308+313 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

It is a precursor in the synthesis of the insecticide synergist piperonyl butoxide, the fragrance piperonal via isosafrole, and the empathogenic/entactogenic drug MDMA.

History

Safrole was obtained from a number of plants, but especially from the sassafras tree (Sassafras albidum), which is native to North America, and from Japanese star anise (Illicium anisatum, called shikimi in Japan).[4] In 1844, the French chemist Édouard Saint-Èvre determined safrole's empirical formula.[5] In 1869, the French chemists Édouard Grimaux (1835–1900) and J. Ruotte investigated and named safrole.[6] They observed its reaction with bromine, suggesting the presence of an allyl group.[7] By 1884, the German chemist Theodor Poleck (1821–1906) suggested that safrole was a derivative of benzene, to which two oxygen atoms were joined as epoxides (cyclic ethers).[8]

In 1885, the Dutch chemist Johann Frederik Eijkman (1851–1915) investigated shikimol, the essential oil that is obtained from Japanese star anise, and he found that, upon oxidation, shikimol formed piperonylic acid,[9] whose basic structure had been determined in 1871 by the German chemist Wilhelm Rudolph Fittig (1835–1910) and his student, the American chemist Ira Remsen (1846–1927).[10] Thus Eijkman inferred the correct basic structure for shikimol.[11] He also noted that shikimol and safrole had the same empirical formula and had other similar properties, and thus he suggested that they were probably identical.[12] In 1886, Poleck showed that upon oxidation, safrole also formed piperonylic acid, and thus shikimol and safrole were indeed identical.[13] It remained to be determined whether the molecule's C3H5 group was a propenyl group (R−CH=CH−CH3) or an allyl group (R−CH2−CH=CH2). In 1888, the German chemist Julius Wilhelm Brühl (1850–1911) determined that the C3H5 group was an allyl group.[14]

Natural occurrence

Safrole is the principal component of brown camphor oil made from Ocotea pretiosa,[3] a plant growing in Brazil, and sassafras oil made from Sassafras albidum.

In the US, commercially available culinary sassafras oil is usually devoid of safrole due to a rule passed by the U.S. FDA in 1960.

Safrole can be obtained through natural extraction from Sassafras albidum and Ocotea cymbarum. Sassafras oil for example is obtained by steam distillation of the root bark of the sassafras tree. The resulting steam distilled product contains about 90% safrole by weight. The oil is dried by mixing it with a small amount of anhydrous calcium chloride. After filtering-off the calcium chloride, the oil is vacuum distilled at 100 °C under a vacuum of 11 mmHg (1.5 kPa) or frozen to crystallize the safrole out. This technique works with other oils in which safrole is present as well.[15][16]

Safrole is typically extracted from the root-bark or the fruit of Sassafras albidum[17] (native to eastern North America) in the form of sassafras oil, or from Ocotea odorifera,[18] a Brazilian species. Safrole is also present in certain essentials oils and in brown camphor oil, which is present, in small amounts, in many plants. Safrole can be found in anise, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper. Safrole can be detected in undiluted liquid beverages and pharmaceutical preparations by high-performance liquid chromatography.[19]

Applications

Safrole is a member of the methylenedioxybenzene group, of which many compounds are used as insecticide synergists; for example, safrole is used as a precursor in the synthesis of the insecticide piperonyl butoxide. Safrole is also used as a precursor in the synthesis of the drug ecstasy (MDMA, N-methyl-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine). Before safrole was banned by the US FDA in 1960 for use in food, it was used as a food flavour for its characteristic ‘candy-shop’ aroma. It was used as an additive in root beer, chewing gum, toothpaste, soaps, and certain pharmaceutical preparations.

Safrole exhibits antibiotic[20] and anti-angiogenic[21] functions.

Synthesis

It can be synthesized from catechol[22] first by conversion to methylenedioxybenzene, which is brominated and coupled with allyl bromide.[23]

Safrole is a versatile precursor to many compounds. Examples are N-acylarylhydrazones, isosters,[24] aryl-sulfonamide derivatives,[25] acidic sulfonylhydrazone derivatives,[26] benzothiazine derivatives.[27] and many more.

Isosafrole

Isosafrole is produced synthetically from safrole. It is not found in nature. Isosafrole comes in two forms, trans-isosafrole and cis-isosafrole. Isosafrole is used as a precursor for the psychoactive drug MDMA (ecstasy). When safrole is metabolized several metabolites can be identified. Some of these metabolites have been shown to exhibit toxicological effects, such as 1′-hydroxysafrole and 3′-hydroxysafrole in rats. Further metabolites of safrole that have been found in urine of both rats and humans include 1,2-dihydroxy-4-allylbenzene or 1(2)-methoxy-2(1)hydroxy-4-allylbenzene.[28]

Metabolism

Safrole can undergo many forms of metabolism. The two major routes are the oxidation of the allyl side chain and the oxidation of the methylenedioxy group.[29] The oxidation of the allyl side chain is mediated by a cytochrome P450 complex, which will transform safrole into 1′-hydroxysafrole. The newly formed 1′-hydroxysafrole will undergo a phase II drug metabolism reaction with a sulfotransferase enzyme to create 1′-sulfoxysafrole, which can cause DNA adducts.[30] A different oxidation pathway of the allyl side chain can form safrole epoxide. So far, this has only been found in rats and guinea pigs. The formed epoxide is a small metabolite due to the slow formation and further metabolism of the compound. An epoxide hydratase enzyme will act on the epoxide to form dihydrodiol, which can be secreted in urine.

The metabolism of safrole through the oxidation of the methylenedioxy proceeds via the cleavage of the methylenedioxy group. This results in two major metabolites: allylcatechol and its isomer, propenylcatechol. Eugenol is a minor metabolite of safrole in humans, mice, and rats. The intact allyl side chain of allylcatechol may then be oxidized to yield 2′,3′-epoxypropylcatechol. This can serve as a substrate for an epoxide hydratase enzyme, and will hydrate the 2′,3′-epoxypropylcatechol to 2′,3′-dihydroxypropylcatechol. This new compound can be oxidized to form propionic acid (PPA),[29] which is a substance that is related to an increase in oxidative stress and glutathione S-transferase activity. PPA also causes a decrease in glutathione and Glutathione peroxidase activity.[31] The epoxide of allylcatechol may also be generated from the cleavage of the methylenedioxy group of the safrole epoxide. The cleavage of the methylenedioxy ring and the metabolism of the allyl group involve hepatic microsomal mixed-function oxidases.[29]

Toxicity

Toxicological studies have shown that safrole is a weak hepatocarcinogen at higher doses in rats and mice. Safrole requires metabolic activation before exhibiting toxicological effects.[29] Metabolic conversion of the allyl group in safrole is able to produce intermediates which are directly capable of binding covalently with DNA and proteins. Metabolism of the methylenedioxy group to a carbene allows the molecule to form ligand complexes with cytochrome P450 and P448. The formation of this complex leads to lower amounts of available free cytochrome P450. Safrole can also directly bind to cytochrome P450, leading to competitive inhibition. These two mechanisms result in lowered mixed function oxidase activity.

Furthermore, because of the altered structural and functional properties of cytochrome P450, loss of ribosomes which are attached to the endoplasmatic reticulum through cytochrome P450 may occur.[28] The allyl group thus directly contributes to mutagenicity, while the methylenedioxy group is associated with changes in the cytochrome P450 system and epigenetic aspects of carcinogenicity.[28] In rats, safrole and related compounds produced both benign and malignant tumors after intake through the mouth. Changes in the liver are also observed through the enlargement of liver cells and cell death.

In the United States, it was once widely used as a food additive in root beer, sassafras tea, and other common goods, but was banned for human consumption by the FDA after studies in the 1960s suggested that safrole was carcinogenic, causing permanent liver damage in rats;[32][33][34] food products sold there purporting to contain sassafras instead a safrole-free sassafras extract. Safrole is also banned for use in soap and perfumes by the International Fragrance Association.

According to a 1977 study of the metabolites of safrole in both rats and humans, two carcinogenic metabolites of safrole found in the urine of rats, 1′-hydroxysafrole and 3′-hydroxyisosafrole, were not found in human urine.[35] The European Commission on Health and consumer protection assumes safrole to be genotoxic and carcinogenic.[36] It occurs naturally in a variety of spices, such as cinnamon, nutmeg, and black pepper, and herbs such as basil. In that role, safrole, like many naturally-occurring compounds, may have a small but measurable ability to induce cancer in rodents. Despite this, the effects in humans were estimated by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to be similar to risks posed by breathing indoor air or drinking municipally supplied water.[37]

Adverse effects

Besides being a hepatocarcinogen, safrole exhibits further adverse effects in that it will induce the formation of hepatic lipid hydroperoxides.[38] Safrole also inhibits the defensive function of neutrophils against bacteria. In addition to the inhibition of the defensive function of neutrophils, it has also been discovered that safrole interferes with the formation of superoxides by neutrophils.[20] Furthermore, safrole oxide, a metabolite of safrole, has a negative effect on the central nervous system. Safrole oxide inhibits the expression of integrin β4/SOD, which leads to apoptosis of the nerve cells.[39]

Use in MDMA manufacture

Safrole is listed as a Table I precursor under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.[40] Due to their role in the manufacture of MDMA, safrole, isosafrole, and piperonal are Category I precursors under regulation no. 273/2004 of the European Community.[41] In the United States, safrole is currently a List I chemical.

The root bark of American sassafras contains a low percentage of steam-volatile oil, which is typically 75% safrole.[42] Attempts to refine safrole from sassafras bark in mass quantities are generally not economically viable due to low yield and high effort. However, smaller quantities can be extracted quite easily via steam distillation (about 10% of dry sassafras root bark by mass, or about 2% of fresh bark).[43] Demand for safrole is causing rapid and illicit harvesting of the Cinnamomum parthenoxylon tree in Southeast Asia, in particular the Cardamom Mountains in Cambodia.[44] However, it is not clear what proportion of illicitly harvested safrole is going toward MDMA production, as over 90% of the global safrole supply (about 2,000 tonnes or 2,200 short tons per year) is used to manufacture pesticides, fragrances, and other chemicals.[45][46] Sustainable harvesting of safrole is possible from leaves and stems of certain plants.[45][46]

References

- Merck Index (11th ed.). 8287.

- Kamdem, Donatien; Gage, Douglas (2007). "Chemical Composition of Essential Oil from the Root Bark of Sassafras albidum". Planta Medica. 61 (6): 574–5. doi:10.1055/s-2006-959379. PMID 8824955.

- Hickey, Michael J. (1948). "Investigation of the chemical constituents of Brazilian sassafras oil". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 13 (3): 443–6. doi:10.1021/jo01161a020. PMID 18863852.

- The history of research on safrole appears in: Semmler, F.W. (1907). Die Ätherischen Öle nach ihren chemischen Bestandteilen unter Berücksichtigung der geschichtlichen Entwicklung [The volatile oils according to their chemical components with regard to their historical development] (in German). 4. Leipzig, Germany: Veit & Co. pp. 139–144.

- Saint-Èvre (1844). "Recherches sur l'huile essentielle de sassafras" [Investigations of the essential oil of sassafras]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 3rd series (in French). 12: 107–113.; see p. 108.

- Grimaux, E; Ruotte, J. (1869). "Sur l'essence de sassafras" [On the essential oil of sassafras]. Comptes Rendus (in French). 68: 928–930. From p. 928: "Ils sont constitués par une principe oxygéné, la safrol C10H10O2 … " (They [the fractions of essential oil that are safrole] are composed of an oxygenated substance, safrole C10H10O2 … )

- (Grimaux & Ruotte, 1869), p. 929.

- Poleck, Theodor (1884). "Ueber die chemische Constitution des Safrols" [On the chemical composition of safrole]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 17 (2): 1940–1944. doi:10.1002/cber.18840170278. See structural formula on p. 1941.

- Eijkman, J.F. (1885). "Sur les principes constituants de l'Illicium religiosum (Sieb.) (Shikimi-no-ki en japonais)" [On the substances composing Illicium religiosum (Sieb.) (Shikimi-no-ki in Japanese)]. Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas (in French). 4 (2): 32–54. doi:10.1002/recl.18850040202.; see pp. 39–40.

- Fittig, Rud.; Remsen, Ira (1871). "Untersuchungen über die Constitution des Piperins und seiner Spaltungsproducte Piperinsäure und Piperidin" [Investigations into the composition of piperine and its cleavage products piperic acid and piperidine]. Annalen der Chemie (in German). 159 (2): 129–158. doi:10.1002/jlac.18711590202.; see the structural formula for Piperonylsäure on p. 155.

- (Eijkman, 1885), pp. 40–41.

- (Eijkman, 1885), pp. 41–42.

- Poleck, Th. (1886). "Ueber die chemische Structur des Safrols" [On the chemical structure of safrole]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 19: 1094–1098. doi:10.1002/cber.188601901243.

- Brühl, J.W. (1888). "Untersuchungen über die Terpene und deren Abkömmlinge" [Investigations of the terpenes and their derivatives]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 21: 457–477. doi:10.1002/cber.18880210181.; see pp. 474–477.

- Ledgard, J. (2010). Kings Chem Guide Second Edition.

- Perkin, William Henry; Trikojus, Victor Martin (1927). "CCXII.—A synthesis of safrole and o-safrole". Journal of the Chemical Society. 0: 1663–1666. doi:10.1039/JR9270001663.

- Kamdem, Donatien; Gage, Douglas (1995-12-01). "Chemical Composition of Essential Oil from the Root Bark ofSassafras albidum". Planta Medica. 61 (6): 574–575. doi:10.1055/s-2006-959379. ISSN 0032-0943. PMID 8824955.

- Hickey, M. J. (1948-05-01). "Investigation of the chemical constituents of Brazilian sassafras oil". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 13 (3): 443–446. doi:10.1021/jo01161a020. ISSN 0022-3263. PMID 18863852.

- Wisneski, Harris H.; Yates, Ronald L.; Davis, Henry M. (1983). "High-performance liquid chromatographic—fluorometric determination of safrole in perfume, cologne and toilet water". Journal of Chromatography A. 255: 455–461. doi:10.1016/s0021-9673(01)88300-x.

- Hung, Shan-Ling; Chen, Yu-Ling; Chen, Yen-Ting (2003-04-01). "Effects of safrole on the defensive functions of human neutrophils". Journal of Periodontal Research. 38 (2): 130–134. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.01652.x. ISSN 0022-3484. PMID 12608906.

- Zhao, Jing; Miao, Junying; Zhao, Baoxiang; Zhang, Shangli; Yin, Deling (2005-06-01). "Safrole oxide inhibits angiogenesis by inducing apoptosis". Vascular Pharmacology. 43 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2005.04.004. ISSN 1537-1891. PMID 15936989.

- Perkin, William Henry; Trikojus, Victor Martin (1927-01-01). "CCXII.—A synthesis of safrole and o-safrole". J. Chem. Soc. 0: 1663–1666. doi:10.1039/jr9270001663. ISSN 0368-1769.

- "Synthesis of Safrole - [www.rhodium.ws]". erowid.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- Lima, P. C.; Lima, L. M.; da Silva, K. C.; Léda, P. H.; de Miranda, A. L.; Fraga, C. A.; Barreiro, E. J. (2000-02-01). "Synthesis and analgesic activity of novel N-acylarylhydrazones and isosters, derived from natural safrole". European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 35 (2): 187–203. doi:10.1016/s0223-5234(00)00120-3. ISSN 0223-5234. PMID 10758281.

- Lages, A. S.; Silva, K. C.; Miranda, A. L.; Fraga, C. A.; Barreiro, E. J. (1998-01-20). "Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of new flosulide analogues, synthesized from natural safrole". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 8 (2): 183–188. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(97)10216-5. ISSN 0960-894X. PMID 9871651.

- Lima, L.M.; Amarante, E.G.; Miranda, A.L.P.; Fraga, C.A.M.; Barreiro, E.J. (1999). "Synthesis and Antinociceptive Profile of Novel Acidic Sulphonylhydrazone Derivatives From Natural Safrole". Pharmacy and Pharmacology Communications. 5 (12): 673–678. doi:10.1211/146080899128734370.

- Fraga, Carlos A. M.; Barreiro, Eliezer J. (1992-10-01). "The synthesis of a new benzothiazine derivative, related to oxicams, synthesized from natural safrole". Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 29 (6): 1667–1669. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570290652. ISSN 1943-5193.

- Ioannides, C.; Delaforge, M.; Parke, D. V. (1981-10-01). "Safrole: its metabolism, carcinogenicity and interactions with cytochrome P-450". Food and Cosmetics Toxicology. 19 (5): 657–666. doi:10.1016/0015-6264(81)90518-6. ISSN 0015-6264. PMID 7030889.

- Sekizawa, J.; Shibamoto, T. (1982-04-01). "Genotoxicity of safrole-related chemicals in microbial test systems". Mutation Research. 101 (2): 127–140. doi:10.1016/0165-1218(82)90003-9. ISSN 0027-5107. PMID 6808388.

- Jeurissen, Suzanne M. F.; Bogaards, Jan J. P.; Awad, Hanem M.; Boersma, Marelle G.; Brand, Walter; Fiamegos, Yiannis C.; van Beek, Teris A.; Alink, Gerrit M.; Sudhölter, Ernst J. R. (2004-09-01). "Human cytochrome p450 enzyme specificity for bioactivation of safrole to the proximate carcinogen 1'-hydroxysafrole". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 17 (9): 1245–1250. doi:10.1021/tx040001v. ISSN 0893-228X. PMID 15377158.

- MacFabe, Derrick F.; Cain, Donald P.; Rodriguez-Capote, Karina; Franklin, Andrew E.; Hoffman, Jennifer E.; Boon, Francis; Taylor, A. Roy; Kavaliers, Martin; Ossenkopp, Klaus-Peter (2007-01-10). "Neurobiological effects of intraventricular propionic acid in rats: Possible role of short chain fatty acids on the pathogenesis and characteristics of autism spectrum disorders". Behavioural Brain Research. Animal Models for Autism. 176 (1): 149–169. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.025. PMID 16950524. S2CID 3054752.

- O'Mathuna, Donal (10 August 2010). "Does it work? Can sassafras be used as a general tonic?". Irish Times.

- Hagan, Ernest C.; Jenner, Paul M.; Jones, Wm.I.; Fitzhugh, O.Garth; Long, Eleanor L.; Brouwer, J.G.; Webb, Willis K. (1965). "Toxic properties of compounds related to safrole". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 7 (1): 18–24. doi:10.1016/0041-008x(65)90069-4. PMID 14259070.

- Liu, T.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, C.L.; Chi, C.W. (1999). "Safrole-induced Oxidative Damage in the Liver of Sprague–Dawley Rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 37 (7): 697–702. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00055-1. PMID 10496370.

- Benedetti, M; Malnoe, A; Broillet, A (1977). "Absorption, metabolism and excretion of safrole in the rat and man". Toxicology. 7 (1): 69–83. doi:10.1016/0300-483X(77)90039-7. PMID 14422.

- Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on the safety of the presence of safrole (1-allyl-3,4-methylenedioxybenzene) in flavourings and other food ingredients with flavouring properties

- "Ranking Possible Cancer Hazards on the HERP Index" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- Liu, T. Y.; Chen, C. C.; Chen, C. L.; Chi, C. W. (1999-07-01). "Safrole-induced Oxidative Damage in the Liver of Sprague–Dawley Rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 37 (7): 697–702. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00055-1. PMID 10496370.

- Su, Le; Zhao, BaoXiang; Lv, Xin; Wang, Nan; Zhao, Jing; Zhang, ShangLi; Miao, JunYing (2007-02-20). "Safrole oxide induces neuronal apoptosis through inhibition of integrin β4/SOD activity and elevation of ROS/NADPH oxidase activity". Life Sciences. 80 (11): 999–1006. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2006.11.041. PMID 17188719.

- International Narcotics Control Board Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- "Regulation (EC) No 273/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 February 2004 on drug precursors".

- The Merck Index, 13th edition, Merck & Co, Inc, Whitehorse Station, NJ, copyright 2001.

- Ledgard, Jared (2010). Kings Chem Guide (2nd ed.). UVKCHEM, Inc. p. 206. ISBN 9780578058658. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Campbell, Sam (30 August 2009). "Harvested to make Ecstasy, Cambodia's trees are felled one by one". GlobalPost. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Blickman, Tom (February 3, 2009). "Harvesting Trees to Make Ecstasy Drug". The Irrawaddy.

- Rocha, Sérgio F.R.; Ming, Lin Chau (1999). "Piper hispidinervum: A Sustainable Source of Safrole". In Janick, Jules (ed.). Perspectives on new crops and new uses. Alexandria, Virginia: ASHS Press. pp. 479–81. ISBN 978-0-9615027-0-6.