SS Empire Endurance

Empire Endurance was a 8,514 GRT steam cargo liner that was built in 1928 as Alster by Deschimag Werk Vulkan, Hamburg, Germany for the shipping company Norddeutscher Lloyd. In the years leading up to the Second World War Alster carried cargo and passengers between Germany and Australia. After the outbreak of war she was requisitioned by the Kriegsmarine for use as a supply ship.

Alster in 1929 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Namesake: | Alster, a tributary of the river Elbe in Germany |

| Owner: |

|

| Operator: |

|

| Port of registry: | |

| Route: | Germany - Australia (1928–40) |

| Builder: | Deschimag Werk Vulcan, Hamburg |

| Yard number: | 211 |

| Launched: | 5 January 1928 |

| Completed: | 25 February 1928 |

| Out of service: | 20 April 1941 |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | sunk by torpedo |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Cargo liner |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: | 509.9 ft (155.42 m) |

| Beam: | 63.6 ft (19.39 m) |

| Depth: | 30.9 ft (9.42 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 14 knots (26 km/h) |

| Crew: |

|

Alster was captured off Norway on 10 April 1940 by the British destroyer HMS Icarus. Initially serving under the original name as a repair, supply and cargo ship in Norway, she was later passed to the Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) and renamed Empire Endurance. She served until 20 April 1941 when she was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-73 south-east of the islet of Rockall in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Description

The ship was a 8,514 GRT cargo liner. Deschimag Werk Vulkan built her in Hamburg as Alster,[1][2][3] with yard number 211.[2][4]

Alster was 509.9 feet (155.42 m) long, with a beam of 63.6 feet (19.39 m). She had a depth of 30.9 feet (9.42 m). She was assessed at 8,514 GRT, 5,328 NRT,[3] 12,000 DWT.[5] She had four masts, a single funnel, a round stern and a slanted stem.[6]

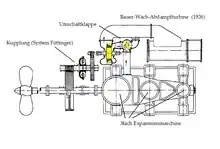

The ship had a single screw driven by both a triple-expansion steam engine and a steam turbine, both built by Deschimag, and coupled by Deschimag's patented Bauer-Wach system. The triple-expansion engine had cylinders of 31 1⁄4 inches (79 cm), 52 3⁄4 inches (134 cm) and 86 5⁄6 inches (221 cm) diameter by 57 1⁄16 inches (145 cm) stroke.[3] Steam exhausted from its low-pressure cylinder passed through a diverter valve to a steam turbine. Via double-reduction gearing and a Föttinger fluid coupling the turbine drove the same shaft as the piston engine.[7][8] Together the two engines developed a total of 6,500 indicated horsepower, which gave her a top speed of 14 knots (26 km/h).[2][4][9]

History

Alster was launched on 5 January 1928, and completed on 25 February 1928.[1][2] She was built for Norddeutscher Lloyd.[5] She was given the code letters QMHG and registered in Bremen.[3] She served on routes between Germany and Australia and East Asia.[2][10] Lloyds Register entries show that she held a passenger certificate from 1934 to 1940. With the change in code letters in 1934, Alster was given the call sign DOEO.[11] She had a crew of 69 and could initially take 14 passengers. In 1930 the passenger capacity was increased to 16.[2][9]

Norwegian Campaign and capture

On 18 March 1940 the Kriegsmarine requisitioned Alster. She was used as a supply ship in Operation Weserübung – the German invasion of Norway, forming part of the invasion's Ausfuhr-Staffel, transporting heavy equipment.[1][12][13] Alster departed Brunsbüttel at 02:00 on 3 April, destined for the North Norwegian port of Narvik. She was one of four supply ships sailing from the Schleswig-Holstein port in support of German forces landing at Narvik on 9 April, under cover of sailing to Murmansk in the Soviet Union.[14] None of these ships made it to their destination.[Note 1] The lack of supplies and artillery would leave the German forces fighting at Narvik vulnerable. Upon reaching Norwegian waters, Alster and the tanker Kattegat, also bound for Narvik, were escorted by the Norwegian torpedo boat HNoMS Trygg as far as Kopervik, where they arrived on 5 April. At Kopervik the German plans suffered a delay because of a lack of pilots to guide the ships northwards, Alster continuing later that day, while Kattegat departed Kopervik only on 6 April. Many of the other supply ships sent out in advance of the invasion also suffered delays, putting the supply part of the invasion plans out of schedule.[17][18] While at Kopervik, Alster and Kattegat were inspected by the torpedo boat HNoMS Stegg, the Norwegians finding nothing irregular.[18] By 8 April, Alster had reached Vestfjorden, where she was hailed by the Norwegian patrol boat HNoMS Syrian, which warned her of the British naval minefield laid in the area earlier that day. Alster steamed to Bodø, to await developments. Two days later, on 10 April, following the outbreak of war between Norway and Germany the previous day, Syrian was despatched by Norwegian authorities to seize Alster off Bodø. When Syrian found Alster, the commander of the small Norwegian patrol boat chose not to board the German vessel as he suspected she was armed and possibly carrying troops. As Alster attempted to escape, Syrian sent out messages to the British warships in the area.[19][20][21][22][23]

On 10 April, Alster was captured by the British destroyer HMS Icarus in Vestfjorden, north of Bodø. When intercepted the German crew made an unsuccessful attempt at scuttling the vessel, setting off one explosive charge.[1][5][12][19][24] The light cruiser HMS Penelope had also been sent after Alster, but had run aground near Bodø and suffered serious damage.[25] With the British capture of Alster, no more German supply ships were heading for Narvik and the forces there,[26] leaving General Eduard Dietl's troops with the supplies on board the tanker Jan Wellem and the large stockpiles of weapons, ammunition, uniforms and food captured at the Norwegian Army base Elvegårdsmoen.[27] At the time of her capture, Alster was under the command of Kapitän Oskar Scharf, who had previously commanded the Blue Riband-holding ocean liner Europa.[28][Note 2]

Initially Alster was brought to the improvised British naval base at Skjelfjord in Lofoten.[12] On arrival at Skjelfjord on 11 April, a prize crew from Penelope took over responsibility for the ship.[30] At Skjelfjord, the captured German crew made an unsuccessful attempt at scuttling Alster by opening the ship's sea valves.[22] While at Skjelfjord Alster, being equipped with derricks, was used to help repair damaged Allied warships. One of the vessels on which emergency repairs were carried out from Alster, was the destroyer HMS Eskimo, which had lost her bow during the naval battles off Narvik.[31][32] Alster was also used as an accommodation ship for the crews of the damaged vessels at Skjelfjord.[33] On 24 April Alster departed Skjelfjord for the Northern Norwegian port of Tromsø, manned by a British prize crew.[34][35] The eight German officers captured on Alster were transferred to the United Kingdom on the British destroyers HMS Cossack and HMS Punjabi.[36] In all, 80 Germans were captured on board Alster, and all were eventually sent to the United Kingdom.[35]

Her cargo of 88 lorries, anti-aircraft guns, spare parts for aircraft, ammunition, communications equipment, coke and 400–500 tons of hay, was unloaded in Tromsø on 27 April, as part of the Allied support of the Norwegian forces fighting the German invasion of their country. The cargo was put to use in the supply and defence of the Tromsø area, except for the hay, which was quarantined by the Norwegian authorities at Ringvassøy for fear of foot-and-mouth disease.[37][38][39][40] The coke on board Alster had been placed by the Germans in a 6 ft (1.83 m) layer covering the deck.[41] The supplies on Alster were transferred to the Norwegians by the Allied naval commander Lord Cork after the Norwegian authorities had made repeated request for weapons and other war matériel, and was intended to be a first effort before the arrival of larger quantities of arms and ammunition promised to the Norwegians.[40][Note 3][Note 4]

The lorries and weapons from Alster were received, assessed and distributed by Norwegian military personnel under the command of Major Karl Arnulf, who had arrived in Tromsø on 7 May 1940, having made his way from German-occupied South Norway.[42] The communications equipment included both a mobile radio transmitter, which was used as a spare for Tromsø radio broadcasting station, as well as large quantities of field telephone equipment which was sent to the units of the Norwegian 6th Division on the Narvik front. The field equipment from Alster replaced the old and worn field telephone systems in use up to that point. Training on the German equipment was provided by Swedish volunteers.[37][43] In order to satisfy British naval regulations with regards to prize cargoes, the British consul in Tromsø observed the unloading of Alster, and wrote an affidavit listing what had been given to the Norwegians, which was sent to the Admiralty.[44] While docked in Tromsø in May 1940, Alster had 70 captive Germans on board.[45] At Tromsø, Alster was manned by Norwegian sailors, replacing the British prize crew.[35]

On 16 May a request was made to the Admiralty for a call sign for Alster, the ship departing Tromsø the next day for Kirkenes in Finnmark, escorted by the anti-submarine whaler HMS Ullswater. She was despatched to the northern port to retrieve a cargo of iron ore. Arriving on 19 May 1940, Alster loaded some 10,000 tons of iron ore over four days, sailing south to the port of Harstad on 22 May, still escorted by HMS Ullswater, as well as the Norwegian patrol boat HNoMS Nordhav II. On 23 May, the British submarine HMS Truant made an unsuccessful attack with two torpedoes on Alster off Havøya, despite efforts having been made to both keep the cargo ship away from the submarine's patrol area, and to warn Truant of the ship's identity. The torpedoes missed, exploding when they hit land. Alster and HMS Ullswater arrived at Harstad on 26 May, with the escort vessel sailing northwards to Hammerfest with mail and provisions for the heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire.[45][46][47] While Alster was at Harstad shipping in the town's harbour was repeatedly subjected to attacks by Luftwaffe Heinkel He 111 bombers, the ships being defended by Gloster Gladiator fighters of the No. 263 Squadron RAF operating from Bardufoss Air Station and anti-aircraft artillery. During one of the attacks on 26 May the ship's Norwegian fireman was mortally wounded by bomb fragments, dying in Harstad Hospital later the same day.[48][49][50]

On 27 May Alster sailed for the United Kingdom in a five-ship convoy which included the crippled HMS Eskimo. In addition to her cargo of iron ore, the ship carried 209 British military personnel, 46 Norwegian military personnel and 72 German prisoners of war. She also transported the "B" gun turret from Eskimo, which had been removed from the destroyer during makeshift repairs. Alster arrived at Scapa Flow on 31 May, unloading her passengers there. Sailing on 3 June, in the company of the passenger steamer St. Magnus and escorted by the destroyers HMS Ashanti and HMS Bedouin, she arrived at Rosyth in Scotland on 4 June 1940.[51][52][53]

As Empire Endurance

Alster was passed to the MoWT and renamed Empire Endurance.[5] She was given the UK official number 164841 and call sign GMJJ. She was registered in Middlesbrough. She was placed under the management of Alfred Booth and Company.[7] Empire Endurance sailed in Convoy FN 255, which left Southend, Essex on 17 August and arrived at Methil, Fife two days later.[54] She then joined Convoy OA 202, which left on 21 August and dispersed at sea on 25 August.[55] Her destination was Montreal, Quebec, Canada, where she arrived on 3 September. Empire Endurance sailed on 12 September for Sydney, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, arriving three days later.[56] She then joined Convoy HX 74, which departed from Halifax, Nova Scotia on 17 September and arrived at Liverpool, Lancashire, United Kingdom on 2 October. She was carrying general cargo stated to be bound for Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland.[57] She left the convoy at the Clyde on 2 October.[56]

Empire Endurance departed on 25 October to join Convoy OB 234,[56] which had departed from Liverpool the previous day and dispersed at sea on 30 October.[58] Her destination was Montreal, where she arrived on 6 November. She departed on 18 November for the Clyde, arriving on 27 November.[56] The ship was declared a prize of war on 10 December 1940, valued at £144,000.[59] She departed on 5 January 1941 to join Convoy OB 270,[56] which had departed from Liverpool that day and dispersed at sea on 8 January.[60] She sailed to Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada, arriving on 17 January. Empire Endurance sailed on 3 February for Halifax, arriving two days later and departing on 9 February for the Clyde, where she arrived on 21 February.[56]

Empire Endurance departed on 23 February for Swansea, Glamorgan, arriving on 1 March. She sailed on 9 March for Avonmouth, Somerset, arriving the next day. She departed on 29 March for Cardiff, Glamorgan, arriving the next day and sailing on 2 April for Newport, Monmouthshire, where she arrived later that day. She sailed on 13 April for Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, where she arrived on 15 April.[56]

On 19 April, Empire Endurance departed from Milford Haven,[56] bound for Cape Town, South Africa and Alexandria, Egypt. She was manned by 90 crew and had five passengers on board. Amongst her cargo were the Fairmile B motor launches ML-1003 and ML-1037. At 03:32 (German time) on 20 April, Empire Endurance was hit amidships by a torpedo fired by U-73, under the command of Helmut Rosenbaum. At the time she was south west of Rockall at 53°05′N 23°14′W. A coup de grâce was fired at 03:57 which hit just under the bridge, breaking her in two. Empire Endurance sank with the loss of 65 crew and one passenger. Among the crew members lost was the captain, Fred J.S. Tucker of the Royal Naval Reserve. On 21 April, the Canadian Flower-class corvette HMCS Trillium picked up twenty crew and four passengers at 52°50′N 22°50′W. They were landed at Greenock, Renfrewshire on 25 May. On 9 May, five crew were rescued by the British cargo liner Highland Brigade. They were landed at Liverpool.[1] Those lost on board Empire Endurance are commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial, London.[61][62]

References

- Notes

- The three other supply ships sailing from Brunsbüttel were Bärenfels, Kattegat and Rauenfels. In addition to these, the tanker Jan Wellem sailed from the German Basis Nord near Murmansk. Jan Wellem was the only German supply ship to reach its destination before the invasion began. While Alster was captured, Bärenfels was redirected to Bergen, Kattegat was sunk by the Norwegian patrol boat HNoMS Nordkapp and Rauenfels was knocked out by the destroyer HMS Havock.[15][16]

- Commodore Oskar Scharf was taken from Norway by the British as a prisoner of war, eventually ending up as the leader of the prisoners of war held in Camp R in Red Rock, Ontario, having been brought to Canada on the liner Duchess of York.[29]

- Northern Norway at the time of the 1940 Norwegian Campaign had no capacity for weapons or ammunition manufacture. The only ammunition available to the Norwegian forces fighting in Northern Norway came from pre-war stocks in military depots. As the campaign progressed artillery ammunition started running low, and ammunition for machine guns and rifles almost ran out.[26]

- The first and only regular transfer of weapons from the British military to their Norwegian counterparts occurred on 31 May, when 5,000 rifles, 100 Bren light machine guns and 500,000 rounds of ammunition were handed over.[42]

- Citations

- "Empire Endurance". Uboat. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Kludas 1998, p. 64

- "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). II. Lloyd's Register. 1930. Retrieved 28 August 2011 – via Plimsoll Ship Data.

- "Alster (1164841)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Mitchell, WH; Sawyer, LA (1995). The Empire Ships. London, New York, Hamburg, Hong Kong: Lloyd's of London Press Ltd. ISBN 1-85044-275-4.

- Schwadtke 1974, p. 137

- "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). II. Lloyd's Register. 1940. Retrieved 28 August 2011 – via Plimsoll Ship Data.

- "Gustav Bauer-Schlichtegroll". The Engineer. 8 January 1954. Retrieved 30 October 2020 – via Grace's Guide to British Industrial History.

- Schwadtke 1974, p. 68-69

- "Shipping". The Times (44962). London. 7 August 1928. col B, p. 2.

- "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). II. Lloyd's Register. 1937. Retrieved 28 August 2011 – via Plimsoll Ship Data.

- Kindell, Don (16 July 2011). "Admiralty War Diaries of World War 2: Vice Admiral, Battlecruiser Squadron, Home Fleet - May to December 1940". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Niehorster, Leo. "Scandinavian Campaign: Equipment Transport Echelon". Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Sandvik 1965 vol. 1, p. 135

- Lunde 2009, pp. 188–189

- Haarr 2009, pp. 66, 68

- Kindell, Don (17 September 2008). "Naval Events, April 1940, Part 1 of 4 Monday 1st – Sunday 7th". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Steen 1958, p. 43

- Kindell, Don (17 September 2008). "Naval Events, April 1940, Part 2 of 4 Monday 8th - Sunday 14th". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Berg and Vollan 1999, pp. 66–67

- Haarr 2009, pp. 66, 333

- Pedersen 2009, p. 224

- Steen 1958, p. 170

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Gerhard Hümmelchen. "Verluste Deutscher Handelsschiffe 1939-1945 und unter deutscher Flagge fahrender ausländischer Schiffe: 1940". Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (in German). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Derry 1952, pp. 46-47

- Lunde 2009, p. 253

- Sandvik 1965 vol. 1, pp. 214–15

- "British Naval Actions at Narvik: Further Pictures". The Times (48596). London. 22 April 1940. col A-F, p. 10.

- Koch 1985, pp. 110–112

- Kindell, Don (16 July 2011). "Admiralty War Diaries of World War 2: Rear Admiral, Second (2nd) Cruiser Squadron - March to December 1940". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Haarr 2009, pp. 353, 370

- Haarr 2010, p. 212

- Haarr 2010, p. 216

- Haarr 2010, p. 217

- Steen 1958, p. 171

- Haarr 2010, p. 433

- Christensen and Pedersen 1995, pp. 413–15

- Haarr 2010, p. 265

- Sandvik 1965 vol. 1, p. 202

- Sandvik 1965 vol. 2, pp. 161–62

- Walker 1989, p. 18

- Sandvik 1965 vol. 2, p. 185

- Sandvik 1965 vol. 2, p. 183

- Grehan and Mace 2015, p. 60

- Kindell, Don (16 July 2011). "Admiralty War Diaries of World War 2: Rear Admiral, First (1st) Cruiser Squadron - March to August 1940". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Haarr 2010, p. 263

- Steen 1958, p. 251

- Ingebrigtsen 1995, pp. 182–183

- Ording 1950, p. 794

- Hafsten 1991, p. 95–96

- Kindell, Don (17 September 2008). "Naval Events, May 1940, Part 4 of 4 Wednesday 22nd – Friday 31st". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Kindell, Don (19 April 2009). "Naval Events, June 1940, Part 1 of 4 Saturday 1st – Friday 7th". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Haarr 2010, p. 436

- Hague, Arnold. "Convoy FN.255 = Convoy FN.55 / Phase 3". FN Convoy Series. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Hague, Arnold. "Convoy OA.202". OA Convoy Series. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Hague, Arnold. "Ship Movements". Port Arrivals / Departures. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Hague, Arnold. "Convoy HX.74". Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Hague, Arnold. "Convoy OB.234". OB Convoy Series. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "The Prize Court". The Times (48796). London. 11 December 1940. col G, p. 2.

- Hague, Arnold. "Convoy OB.270". OB Convoy Series. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "Empire Day to Empire Engineer". Brian Watson. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Kindell, Don (18 April 2009). "Casualty Lists of the Royal Navy and Dominion Navies, World War 2 – 1st - 30th April 1941 - in date, ship/unit & name order". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- Bibliography

- Berg, Johan Helge; Vollan, Olav (1999). Fjellkrigen 1940: Lapphaugen - Bjørnfjell (in Norwegian). Trondheim: Nord-Hålogaland regiment. ISBN 82-995412-0-4.

- Christensen, Pål; Pedersen, Gunnar (1995). Tromsø gjennom 10000 år: Ishavsfolk, arbeidsfolk og fintfolk - 1900-1945 (in Norwegian). Tromsø: Tromsø municipality. ISBN 82-993206-3-1.

- Derry, TK (1952). Butler, JRM (ed.). The campaign in Norway. History of the Second World War: Campaigns Series (1st ed.). London: HMSO.

- Grehan, John; Mace, Martin (2015). The Battle for Norway 1940-1942. Despatches from the Front. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-2-322.

- Haarr, Geirr H (2010). The Battle for Norway – April–June 1940. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-057-4.

- Haarr, Geirr H (2009). The German Invasion of Norway – April 1940. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-032-1.

- Hafsten, Bjørn; Ulf Larsstuvold; Bjørn Olsen; Sten Stenersen (1991). Flyalarm – luftkrigen over Norge 1939–1945 (in Norwegian) (1st ed.). Oslo: Sem og Stenersen AS. ISBN 82-7046-058-3.

- Ingebrigtsen, Guri; Berntsen, Merete (1995). Hverdagsbilder Vestvågøy: 1940–45 (in Norwegian). Stamsund: Orkana Forlag. ISBN 82-91233-06-3.

- Kludas, Arnold (1998). Die Seeschiffe des Norddeutschen Lloyd: 1857 bis 1970 (in German). Augsburg: Bechtermünz Verlag. ISBN 3-86047-262-3.

- Koch, Eric (1985). Deemed suspect: a wartime blunder. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Goodread Biographies. ISBN 0-88780-138-2.

- Lunde, Henrik O (2009). Hitler's pre-emptive war: The Battle for Norway, 1940. Newbury: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-932033-92-2.

- Ording, Arne; Høibo, Gudrun Johnson; Garder, Johan (1950). Våre falne 1939–1945 (in Norwegian). 2. Oslo: Grøndahl.

- Pedersen, Arne Stein (2009). "En høyst risikabel affære" – Sjøkrigen i Norge 1940 (in Norwegian). Bergen: Happy Jam Factory. ISBN 978-82-997358-7-2.

- Sandvik, Trygve (1965). Krigen i Norge 1940 – Operasjonene til lands i Nord-Norge 1940 (in Norwegian). 1. Oslo: Forsvarets Krigshistoriske Avdeling/Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Sandvik, Trygve (1965). Krigen i Norge 1940 – Operasjonene til lands i Nord-Norge 1940 (in Norwegian). 2. Oslo: Forsvarets Krigshistoriske Avdeling/Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Schwadtke, Karl-Heinz (1974). Deutschlands Handelsschiffe 1939–1945 (in German). Oldenburg: Verlag Gerhard Stalling AG. ISBN 3-7979-1840-2.

- Steen, Erik Anker (1958). Norge sjøkrig 1940-1945 – Sjøforsvarets kamper og virke i Nord-Norge 1940 (in Norwegian). 4. Oslo: Forsvarets Krigshistoriske Avdeling/Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Walker, Robert (1989). Krigen i Lofoten (in Norwegian). Svolvær: Forlaget Nord. ISBN 8290552076.