SIG Sauer System

The SIG Sauer System is a type of action found in self-loading handguns. It is a refinement of designs based on the work of both John M. Browning and Charles Petter which began with the Browning Model 1910, progressed to the French Model 1935A, and later the SIG P210 handgun. This action first appeared in the United States on the Browning BDA (Browning Double Action) .45 ACP caliber handgun around 1975. It represents a design which optimizes the cost of production of handguns while instilling high levels of accuracy and dependability. It is the basis for several SIG Sauer, Inc. designs which have been widely adopted for police, military, and civilian use and is the action used in the M17 and M18 sidearms of the United States Armed Forces. It has become a highly copied design found in many parts of the world today.[1]

History

When introduced in 1975, the new SIG Sauer P220 handgun used a new type of action called the SIG Sauer System. It was a development of the French Model 1935A's action which SIG had licensed in 1947. The SIG Sauer handgun first appeared around 1975 after the Swiss company Schweizerische Industrie Gesellschaft (Swiss Industrial Company, or SIG) developed a new type of industrial production machinery known then as an automatic screw machine. This was an automated type of milling machine which could perform several machining operations without a great deal of human input. Today that machine is referred to as a Swiss type of CNC (computer numerical control) machine. This type of machine allowed for a greatly reduced cost of manufacture of whatever part it is used to produce. This is of particular concern in the production of firearms.

.jpg.webp)

As an example, the Luger pistol which appeared around 1908 had over 650 machine operations and 450 hand fitting operations needed to complete its construction.[2] The cost of this in time and labor was very high. As a result, the Luger (made by Deutsche Waffen & Munitions, or DWM) was one of the most expensive handguns available anywhere in the world. The Luger was replaced by Carl Walther's P38 as a sidearm. The Walther design had several innovations, the most important of which was that it was easier and cheaper to manufacture.[3]

In 1947, SIG had licensed from the French SACM a design for a handgun which had been developed in 1936 for a French Army contract.[4] This was designated as the P210 by SIG. It was renowned worldwide as an extremely accurate handgun. But like the Luger, it was very expensive to produce. With the development of the new machinery, SIG was able to produce a simplified version of the P210 handgun which became the P220, and later the P225 (adopted as the P6 in Germany).

Browning influence

The French Model 1935A handgun was the result of a French requirement for a higher capacity handgun than was commonly available at that time. A competition was held in which John Browning, through the Belgian Browning company, submitted a design that he produced in 1933 just prior to his death. This design was Browning's own simplification of his original 1910 design which had been adopted in a modified form by the United States military and designated the M1910 (subsequently the M1911A1). The Browning design was not adopted, but a modification of it known as the Petter-Browning system was adopted.

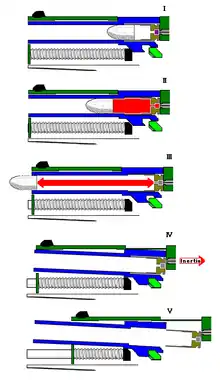

The Browning 1910 design consists of a short-recoil action in which the barrel and slide of the handgun ride on a steel frame. When fired, the inertia of the bullet's motion causes the barrel and frame to recoil together for a distance until the gas pressure in the barrel drops after the bullet leaves the barrel. As the bullet is being propelled down the barrel, it is pushed by high-pressure gases which are formed due to the combustion of the propellant contained in the metallic case. When the bullet first starts to move, the pressure in the cartridge case and barrel rises to more than 16,000 pounds per square inch (110,000 kPa). As the bullet moves down the barrel, the pressures begin to dissipate due to the greater volume of the space from the shell casing to the bullet as it travels through the barrel, and then drops precipitously as the bullet leaves the barrel, which causes the gases to expand very rapidly in the atmosphere since they are now no longer pressurized.

Because the weight of the combined barrel and slide are much greater than the weight of the bullet, the barrel and slide will resist being moved by the inertia of the bullet and thus will move much more slowly in recoil. The bullet will leave the barrel and the pressure will drop to a much lower level after the barrel and slide have recoiled for some distance. The barrel and slide are held together by interlocking grooves that are machined into the top of the breech of the barrel and the inner top surface of the slide. The barrel is held up against the slide so that these grooves remain locked as the slide assembly recoils for some distance. After recoiling a distance sufficient for the gas pressure in the barrel to reduce to a level that is safe, the barrel is pulled downward by a moving link and the barrel is unlocked from its mating with the slide. The slide at this point is moving with some speed and continues to move rearward under its inertia.

The slide mechanism which pushes the cartridge into the breech of the barrel also contains a claw (called an extractor) which slips over the rim of the cartridge and grips it. During recoil, the extractor pulls the now-empty cartridge case from the chamber. As the slide nears its full rearward motion, a projection in the slide, known as the ejector, is struck by the moving cartridge case and, being located on one side of the slide and offset to that side, causes the moving case to fly out of the handgun action.

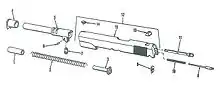

The barrel and slide are pushed into their forward position by the recoil spring and guide, which are located in the slide area just below the barrel. At the front of the barrel on the original Browning 1910 design, there is a barrel bushing which holds the front of the barrel in position and is machined so that the barrel can pivot downward at the ends of its recoil without binding. The bushing has a protuberance which retains the front of the recoil spring assembly. During disassembly, this bushing is rotated to allow the removal of the spring and guide for cleaning.

At the rear of the barrel is a pivoting link. This link rides on a cylindrical pin which is part of the takedown lever. As the barrel recoils and reaches the rearward most travel, the link rotates around the takedown pin and pulls the barrel downward. This causes the ribs on the top of the barrel to disengage, at which point the slide continues to move rearward to eject the empty cartridge case.

Once the case has been ejected, the slide and breechblock that it contains have now moved past the area of the magazine. A spring in the magazine pushes the next cartridge in the magazine upward as the empty case is ejected. The slide then returns forward to its battery position. As it moves, the breechblock strikes the cartridge that is at the top of the magazine and pushes it into the chamber. Once it has fully returned to its locked position, it is referred to as being "in battery". This completes the reloading cycle.

If the last cartridge in the magazine has been fired, the plate in the magazine that pushed the cartridges upward pushed a lever upward that will catch the slide and hold it open. This is a clear indication that the handgun is now empty of ammunition. A full magazine can now replace the empty one. Once the magazine is inserted and locked into place, pushing on the external part of the hold open lever causes the cartridge in the magazine to be loaded into the chamber and completes the magazine/chamber reloading process.

Browning, Petter, and SIG change the design

When examining the design of the Browning 1910, it can be seen there are a number of parts that introduce inaccuracy in the movement of the barrel as it cycles. The barrel bushing, slide, pivoting link and the mating of the groves in the slide must all move consistently for the handgun to function. But to function reliably, particularly as the handgun starts to become fouled with powder residue or dirt, these parts must be machined so the dirt that builds up will not cause them to stop functioning. As a result, the Colt M1911 was regarded as an inaccurate handgun.[5]

Browning and Petter both realized that there were accuracy problems with the design. The loose fit of the barrel bushing was resolved by removing it. The sloppy action of the barrel link was replaced by a solid metal cam. In 1975, SIG removed the barrel and slide grooves altogether using the ejection port as the locking mechanism by machining the barrel chamber to form a ledge which was now the lock for the barrel to slide.

This refinement of the Browning/Petter Browning design is known as the SIG Sauer system. It first appeared in the United States in the Browning BDA handguns made in .45 ACP and 9x19mm Parabellum calibers. These appeared in 1975. Stamped into the slide on the Browning BDA is "SIG Sauer System."

Many of the most modern handgun designs now use this system.

Creation of SIG Sauer

Due to export restrictions, SIG formed a partnership with German J.P. Sauer & Sohn in order to manufacture their new series of handguns. The resulting product name was SIG Sauer. Initially, this applied to the company that is now in Eckernförde, Germany, and is known as SIG Sauer, GmbH, but another branch of this company was formed in the United States. This was initially known as Sigarms but is now SIG Sauer Inc. and is headquartered in Newington, New Hampshire. Since 2000, the two SIG Sauer companies are independently operated but are both owned by Luke and Ortmeier Gruppe of Germany.[1]

References

- "SIG Sauer History and Development". Gunivore. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "The Parabellum Story – Mauser's Luger". Forgotten Weapons. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "The Walther P38: Godfather of the modern combat handgun". Guns.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Bringing an icon to America–'New Improved' SIG Sauer P210 Review". Guns & Tech. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Classic Handguns of the 20th Century. Krause Publications Craft. 2004. ISBN 0-87349-576-4. Retrieved 15 January 2018.