Sémiramis (tragedy)

Sémiramis (1746) is a tragedy in five acts by Voltaire, first performed in 1748 and published in 1749.

Action

The plot is very similar to that of Voltaire's earlier unsuccessful tragedy Ériphyle.[1]:185 The action takes place in a courtyard in front of the palace of Sémiramis in Babylon, in front of the Hanging Gardens. Sémiramis, after having her husband Ninos poisoned, now rules the Babylonian Empire. She now decides to marry the stranger Arsace instead of Assur, Prince of the Bélus. Arsace learns that he is in fact Ninias, the son, presumed dead, of Sémiramis and Ninos. Assur tries to eliminate his rival Arsace; Sémiramis tries to save her son, but is mortally wounded by him in a scuffle. Arsace/Ninias thereby avenges his father's death.[2]:86

Dispute with Crébillon

When Voltaire was given the opportunity to write a piece of grand theatre to commemorate the birth of the dauphin’s first son in 1746, he selected the apparently inappropriate story of the ancient queen Semiramis. The theme of a ruler who poisoned her husband, fell in love with her own son and ultimately met her death was not one that appeared to have the expected celebratory qualities. Voltaire claimed that the play would restore French tragedy to its classical glory, an aspiration worthy of a new prince. In the event the birth went badly and the young dauphine Maria Teresa died. [3] The play was therefore not performed at court or in the public theatre, but Voltaire sent a copy to Frederick the Great in February 1747.

Sémiramis became a focal point for the bitter dispute between Voltaire and his older rival Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon. Crébillon was favoured by Madame de Pompadour, who secured him the position of royal librarian and gave him a pension. Crébillon was also the royal censor, and had previously irritated Voltaire by demanding changes in Temple du goût (1733) and then stopped the performances of Mahomet (1742) and La Mort de César (1743).[4][1]:82 Voltaire decided to retaliate by selecting, one after another, classical themes for his tragedies which Crébillon had used earlier, to demonstrate the superiority of his own treatment of the material. The first of these plays, Sémiramis, dealt with a plot Crébillon had used in his tragedy of the same name in 1717.[5] He followed this up with Oreste (1750) and Rome sauvée (1752).[6][7]

Crébillon was angry with Voltaire's choice of Sémiramis. He first required a number of irritating changes from Voltaire, and then immediately authorised the publication of a parody of the play - not uncommon at the time - which was performed at the Comédie Italienne and then for the court at Fontainebleu, and which Voltaire felt singled him out for ridicule.[8][2]:71

The staging of the play became another battleground between the followers of Crébillon and partisans of Voltaire. Traditionally part of the stage in the Comédie-Française was occupied by gentlemen spectators, and Crébillon supported this status quo. However Voltaire wanted grand and lavish sets, and the theatrical effect of a ghost would be lost if there were spectators sitting close to where he appeared. He therefore insisted on clearing the stage.[9][1]:187–190

Critical reception

The play was first performed at the court of Stanisław Leszczyński in Lunéville, but its public premiere was on August 29, 1748 at the Comédie-Française. It became one of Voltaire's greatest stage successes, not only in France but internationally, as it was performed in many European capitals. St. Petersburg was an exception, as Catherine the Great found the theme of a queen murdering her husband uncongenial. Voltaire's text was the basis for the libretto by Gaetano Rossi used by Gioachino Rossini for his opera Semiramide.[10] An English translation of the play was printed in 1760, and adaptations of it were staged at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1776 and the King's Theatre, Haymarket in 1794.[11]

Printed editions

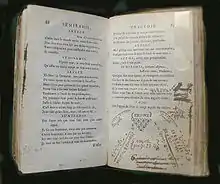

In 1749 a version of the play, printed by Lambert, appeared without naming the author. Three other unauthorized printings followed in the same year. Voltaire added a treatise on ancient and modern tragedy as a preface and an appendix in honour of the dead officers of the War of Austrian Succession.

References

- Shibuya, Naoki (2014). Tradition et Modernité: Étude des Tragédies de Voltaire (PhD). Université de la Sorbonne nouvelle, Paris III. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- Siegfried Detemple: Semiramis, in: Voltaire: Die Werke. Katalog zum 300. Geburtstag. Reichert, Wiesbaden 1994

- Judith P. Zinsser (2007-11-27). Emilie Du Chatelet: Daring Genius of the Enlightenment. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-101-20184-8.

- Ian Davidson (2012-03-12). Voltaire: A Life. Pegasus Books. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-1-68177-039-0.

- Jean François Marmontel (1807). Memoirs of Marmontel, written by himself. Printed by Abel Kickson, for Brisban & Brannan, New York. p. 114.

- Voltaire (1827). Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire: ptie. Oeuvres poétiques. J. Didot aîné. p. 11.

- The Historic Gallery of Portraits and Paintings: Or, Biographical Review. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. 1808. p. 284.

- Marvin A. Carlson (1998). Voltaire and the Theatre of the Eighteenth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 73-4. ISBN 978-0-313-30302-9.

- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1840). Voltaire, Rousseau, Condorcet, Mirabeau, Madame Roland, Madame De Stael. Lea and Blanchard. p. 69.

- Beghelli, Marco. "Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) Semiramide". naxos.com. Naxos. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- Besterman, Theodore (1959). Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century (PDF) (vol VIII ed.). Geneva: Institut et Musee Voltaire. pp. 103–104. Retrieved 3 November 2018.