Rostow's stages of growth

Rostow's stages of economic growth model is one of the major historical models of economic growth. It was published by American economist Walt Whitman Rostow in 1960. The model postulates that economic growth occurs in five basic stages, of varying length:[1]

- The traditional society

- The preconditions for take-off

- The take-off

- The drive to maturity

- The age of high mass-consumption

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

Rostow's model is one of the more structuralist models of economic growth, particularly in comparison with the "backwardness" model developed by Alexander Gerschenkron, although the two models are not mutually exclusive.

Rostow argued that economic take-off must initially be led by a few individual economic sectors. This belief echoes David Ricardo's comparative advantage thesis and criticizes Marxist revolutionaries' push for economic self-reliance in that it pushes for the "initial" development of only one or two sectors over the development of all sectors equally. This became one of the important concepts in the theory of modernization in social evolutionism.

Overview

In addition to the five stages he had proposed in The Stages of Economic Growth in 1960, Rostow discussed the sixth stage beyond high mass-consumption and called it "the search for quality" in 1971.[2] Below is an outline of Rostow's six stages of growth:

- The traditional society

- characterized by subsistence agriculture or hunting and gathering; almost wholly a "primary" sector economy

- limited technology

- Some advancements and improvements to processes, but limited ability for economic growth because of the absence of modern technologies, lack of class or individual economic mobility, with stability prioritized and change seen negatively

- This is where society generally begins before progressing towards the next stages of growth

- No centralized nations or political systems.

- The preconditions for take-off

- External demand for raw materials initiates economic change.

- Development of more productive, commercial agriculture and cash crops not consumed by producers and/or largely exported.

- Widespread and enhanced investment in changes to the physical environment to expand production (i.e. irrigation, canals, ports)

- Increasing spread of technology and advances in existing technologies

- Changing social structure, with previous social equilibrium now in flux

- Individual social mobility begins

- Development of national identity and shared economic interests.

- The take-off

- Urbanization increases, industrialization proceeds, technological breakthroughs occur.

- "Secondary" (goods-producing) sector expands and ratio of secondary vs. primary sectors in the economy shifts quickly towards secondary.

- Textiles and apparel are usually the first "take-off" industry, as happened in Great Britain's classic "Industrial Revolution"

- An Example of the Take-off phase is the Agriculture (Green) Revolution in the 1960s.

- The drive to maturity

- Diversification of the industrial base; multiple industries expand and new ones take root quickly

- Manufacturing shifts from investment-driven (capital goods) towards consumer durables and domestic consumption

- Rapid development of transportation infrastructure.

- Large-scale investment in social infrastructure (schools, universities, hospitals, etc.)

- The age of mass-consumption

- the industrial base dominates the economy; the primary sector is of greatly diminished weight in the economy and society

- widespread and normative consumption of high-value consumer goods (e.g. automobiles)

- consumers typically (if not universally), have disposable income, beyond all basic needs, for additional goods

- Urban society (a movement away from rural countrysides to the cities)

- Beyond consumption (The search for quality)

- age of diminishing relative marginal utility as well as an age for durable consumer goods

- large families and Americans feel as if they were born into a society that has high economic security and high consumption

- a stage where its merely speculation on whether there is further consumer diffusion or what the new generation will bring for growth

Rostow claimed that these stages of growth were designed to tackle a number of issues, some of which he identified himself, writing:

"Under what impulses did traditional, agricultural societies begin the process of their modernization? When and how did regular growth become a built-in feature of each society? What forces drove the process of sustained growth along and determined its contours? What common social and political features of the growth process may be discerned at each stage? What forces have determined relations between the more developed and less developed areas; and what relation if any did the relative sequence of growth bear to outbreak of war? And finally where is compound interest taking us? Is it taking us to communism; or to the affluent suburbs, nicely rounded out with social overhead capital; to destruction; to the moon; or where?"[3][4]

Rostow asserts that countries go through each of these stages fairly linearly, and set out a number of conditions that were likely to occur in investment, consumption, and social trends at each state. Not all of the conditions were certain to occur at each stage, however, and the stages and transition periods may occur at varying lengths from country to country, and even from region to region.[5]

Theoretical framework

Rostow's model is a part of the liberal school of economics, laying emphasis on the efficacy of modern concepts of free trade and the ideas of Adam Smith. It disagrees with Friedrich List's argument which states that economies which rely on exports of raw materials may get "locked in", and would not be able to diversify, regarding this Rostow's model states that economies may need to depend on raw material exports to finance the development of industrial sector which has not yet of achieved superior level of the competitiveness in the early stages of take-off. Rostow's model does not disagree with John Maynard Keynes regarding the importance of government control over domestic development which is not generally accepted by some ardent free trade advocates. The basic assumption given by Rostow is that countries want to modernize and grow and that society will agree to the materialistic norms of economic growth.[6]

Stages of development

The traditional society

An economy in this stage has a limited production function which barely attains the minimum level of potential output. This does not entirely mean that the economy's production level is static. The output level can still be increased, as there was often a surplus of uncultivated land which can be used for increasing agricultural production. Modern science and technology has yet to be introduced. As a result, these pre-Newtonian societies, unaware of the possibilities to manipulate the external world, rely heavily on manual labor and self-sufficiency to survive.[7] States and individuals utilize irrigation systems in many instances, but most farming is still purely for subsistence. There have been technological innovations, but only on ad hoc basis. All of that this can result in increases in output, but never beyond an upper limit which cannot be crossed. Trade is predominantly regional and local, largely done through barter, and the monetary system is not well developed. Investment's share never exceeds 5% of total economic production. Countries in this stage could include Ghana and Togo.

Wars, famines and epidemics like plague cause initially expanding populations to halt or shrink, limiting the single greatest factor of production: human manual labor. Volume fluctuations in trade due to political instability are frequent; historically, trading was subject to great risk and transport of goods and raw materials was expensive, difficult, slow and unreliable. The manufacturing sector and other industries have a tendency to grow but are limited by inadequate scientific knowledge and a "backward" or highly traditionalist frame of mind which contributes to low labour productivity. In this stage, some regions are entirely self-sufficient.

In settled agricultural societies before the Industrial Revolution, a hierarchical social structure relied on near-absolute reverence for tradition, and an insistence on obedience and submission. This resulted in concentration of political power in the hands of landowners in most cases; everywhere, family and lineage, and marriage ties, constituted the primary social organization, along with religious customs, and the state only rarely interacted with local populations and in limited spheres of life. This social structure was generally feudalistic in nature. Under modern conditions, these characteristics have been modified by outside influences, but the least developed regions and societies fit this description quite accurately.

The preconditions for take-off

In the second stage of economic growth, the economy undergoes a process of change for building up of conditions for growth and take off. Rostow said that these changes in society and the economy had to be of fundamental nature in the socio-political structure and production techniques.[4] This pattern was followed in Europe, parts of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. There is also a second or third pattern in which he said that there was no need for change in socio-political structure because these economies were not deeply caught up in older, traditional social and political structures. The only changes required were in economic and technical dimensions. The nations which followed this pattern were in North America and Oceania (New Zealand and Australia).

There are three important dimensions to this transition: firstly, the shift from an agrarian to an industrial or manufacturing society begins, albeit slowly. Secondly, trade and other commercial activities of the nation broaden the market's reach not only to neighboring areas but also to far-flung regions, creating international markets. Lastly, the surplus attained should not be wasted on the conspicuous consumption of the land owners or the state, but should be spent on the development of industries, infrastructure and thereby prepare for self-sustained growth of the economy later on. Furthermore, agriculture becomes commercialized and mechanized via technological advancement; shifts increasingly towards cash or export-oriented crops, and there is a growth of agricultural entrepreneurship.[8]

The strategic factor is that the investment level should be above 5% of the national income. This rise in investment rate depends on many sectors of the economy. According to Rostow capital formation depends on the productivity of agriculture and the creation of social overhead capital. Agriculture plays a very important role in this transition process as the surplus quantity of the product is to be utilized to support an increasingly urban population of workers and also becomes a major exporting sector, earning foreign exchange for continued development and capital formation. Increases in agricultural productivity also lead to the expansion of the domestic markets for manufactured goods and processed commodities, which adds to the growth of investment in the industrial sector.

Social overhead capital creation can only be undertaken by the government, in Rostow's view. Government plays the driving role in the development of social overhead capital as it is rarely profitable, it has a long gestation period, and the pay-offs accrue to all economic sectors, not primarily to the investing entity; thus the private sector is not interested in playing a major role in its development.

All these changes effectively prepare the way for "take-off" only if there is a basic change in the attitude of society towards risk-taking, changes in the working environment, and openness to change in social and political organizations and structures. According to Rostow, the preconditions to take-off begins from an external intervention by more developed and advanced societies, which "set in motion ideas and sentiments which initiated the process by which a modern alternative to the traditional society was constructed out of the old culture."[9] The pre-conditions of take-off closely track the historic stages of the (initially) British Industrial Revolution.[10]

Referring to the graph of savings and investment, notably, there is a steep increase in the rate of savings and investment from the stage of "Pre Take-off" till "Drive to Maturity:" then, following that stage, the growth rate of savings and investment moderates. This initial and accelerating steep increase in savings and investment is a pre-condition for the economy to reach the "Take-off" stage and far beyond.

The take-off

This stage is characterized by dynamic economic growth. As Rostow suggests, all is premised on a sharp stimulus (or multiple stimuli) that is/are any or all of economic, political and technological change. The main feature of this stage is rapid, self-sustained growth.[4][10] Take-off occurs when sector led growth becomes common and society is driven more by economic processes than traditions. At this point, the norms of economic growth are well established and growth becomes a nation's "second nature" and a shared goal.[1] In discussing the take-off, Rostow is noted to have adopted the term "transition", which describes the process of a traditional economy becoming a modern one. After take-off, a country will generally take as long as fifty to one hundred years to reach the mature stage according to the model, as occurred in countries that participated in the Industrial Revolution and were established as such when Rostow developed his ideas in the 1950s.

Per Rostow there are three main requirements for take-off:

1. The rate of productive investment should rise from approximately 5% to over 10% of national income or net national product

2. The development of one or more substantial manufacturing sectors, with a high rate of growth;

3. The existence or quick emergence of a political, social and institutional framework which exploits the impulses to expansion in the modern sector and the potential external economy effects of the take-off.[3]

The third requirement implies that the needed capital must be mobilized from domestic resources and steered into the economy, rather than into domestic or state consumption. Industrialization becomes a crucial phenomenon as it helps to prepare the basic structure for structural changes on a massive scale. Rostow says that this transition does not follow a set trend as there are a variety of different motivations or stimulus which began this growth process.

Take off requires a large and sufficient amount of loanable funds for expansion of the industrial sector which generally come from two sources which are:

- Shifts in income flows by way of taxation, implementation of land reforms and various other fiscal measures.

- Re-investment of profits earned from foreign trade as has been observed in many East Asian countries. While there are other examples of "Take-off" based on rapidly increasing demand for domestically produced goods for sale in domestic markets, more countries have followed the export-based model, overall and in the recent past. The US, Canada, Russia and Sweden are examples of domestically based "take-off"; all of them, however, were characterized by massive capital imports and rapid adoption of their trading partners' technological advances.[4][11] This entire process of expansion of the industrial sector yields an increase in rate of return to some individuals who save at high rates and invest their savings in the industrial sector activities. The economy exploit their underutilized natural resources to increase their production.[1]

The take-off also needs a group of entrepreneurs in the society who pursue innovation and accelerate the rate of growth in the economy. For such an entrepreneurial class to develop, firstly, an ethos of "delayed gratification", a preference for capital accumulation over expenditure, and high tolerance of risk must be present. Secondly, entrepreneurial groups typically develop because they can not secure prestige and power in their society via marriage, via participating in well-established industries, or through government or military service (among other routes to prominence) because of some disqualifying social or legal attribute; and lastly, their rapidly changing society must tolerate unorthodox paths to economic and political power.

The ability of a country to make it through this stage depends on the following major factors:

- Existence of enlarged, sustained effective demand for the product of key sectors.

- Introduction of new productive technologies and techniques in these sectors.

- The society's increasing capacity to generate or earn enough capital to complete the take-off transition.

- Activities in the key sector should induce a chain of growth in other sectors of the economy, that also develop rapidly.

An example of a country in the Take-off stage of development is Equatorial Guinea. It has the largest increases in GDP growth since 1980 and the rate of productive investment has risen from 5% to over 10% of income or product.

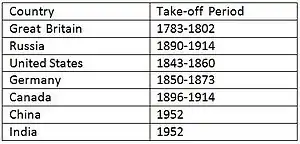

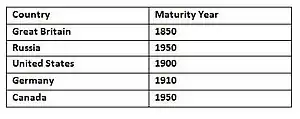

In the table note that Take-off periods of different countries are the same as the industrial revolution in those countries.

The drive to maturity

After take-off, there follows a long interval of sustained growth known as the stage of drive to maturity. Rostow defines it "as the period when a society has effectively applied the range of modern technology to the bulk of its resources."[3][4] Now regularly growing economy drives to extend modern technology over the whole front of its economic activity. Some 10-20% of the national income is steadily invested, permitting output regularly to outstrip the increase in population. The makeup of the economy changes unceasingly as technique improves, new industries accelerate, older industries level off. The economy finds its place in the international economy: goods formerly imported are produced at home; new import requirements develop, and new export commodities to match them. The leading sectors in an economy will be determined by the nature of resource endowments and not only by technology.

On comparing the dates of take-off and drive to maturity, these countries reached the stage of maturity in approximately 60 years.

The structural changes in the society during this stage are in three ways:

- Work force composition in agriculture shifts from 75% of the working population to 20%. The workers acquire greater skill and their wages increase in real terms.

- The character of leadership changes significantly in the industries and a high degree of professionalism is introduced

- Environmental and health cost of industrialization is recognized and policy changes are thus made.

During this stage a country has to decide whether the industrial power and technology it has generated is to be used for the welfare of its people or to gain supremacy over others, or the world in toto.

A prime example of a country in the Drive to Maturity stage is South Africa. It is developing a world-class infrastructure- including a modern transport network, widely available energy, and sophisticated telecommunications facilities. Additionally, the commercial farm sector shed 140,000 jobs, a decline of roughly 20%, in the eleven-year period from 1988 to 1998.

This diversity leads to reduction in poverty rate and increasing standards of living, as the society no longer needs to sacrifice its comfort in order to build up certain sectors.[12]

The age of high mass-consumption

The age of high mass-consumption refers to the period of contemporary comfort afforded by many western nations, wherein consumers concentrate on durable goods, and hardly remember the subsistence concerns of previous stages. Rostow uses the Buddenbrooks dynamics metaphor to describe this change in attitude. In Thomas Mann's 1901 novel, Buddenbrooks, a family is chronicled for three generations. The first generation is interested in economic development, the second in its position in society. The third, already having money and prestige, concerns itself with the arts and music, worrying little about those previous, earthly concerns. So too, in the age of high mass-consumption, a society is able to choose between concentrating on military and security issues, on equality and welfare issues, or on developing great luxuries for its upper class. Each country in this position chooses its own balance between these three goals. There is a desire to develop an egalitarian society and measures are taken to reach this goal. According to Rostow, a country tries to determine its uniqueness and factors affecting it are its political, geographical and cultural structure and also values present in its society.[12]

Historically, the United States is said to have reached this stage first, followed by other western European nations, and then Japan in the 1950s.[4]

Beyond consumption (the search for quality)

When proposed, this step is more of a theoretical speculation by Rostow rather than an analytical step in the process by Rostow.[13] Individuals begin having larger families and do not value income as a pre-requisite for more vacation days. Consumer products become more durable and more diverse.[13] New Americans will behave in a way where the high economic security and level mass consumption is considered normal. Rostow does make the point that it is possible with the large baby boom it could either cause economic issues or dictate an even larger diffusion of consumer goods.[13] With increasing urban and suburban population there will be undoubtedly an increase in consumer goods and services as well.[13]

This stage was later discussed in Rostow's book Politics and the Stages of Growth published in 1971, in which he called the stage "the search for quality".[2]

Criticism of the model

- Rostow is historical in the sense that the end result is known at the outset and is derived from the historical geography of a developed, bureaucratic society.

- Rostow is mechanical in the sense that the underlying motor of change is not disclosed and therefore the stages become little more than a classificatory system based on data from developed countries.

- His model is based on American and European history and defines the American norm of high mass-consumption as integral to the economic development process of all industrialized societies.

- His model assumes the inevitable adoption of Neoliberal trade policies which allow the manufacturing base of a given advanced polity to be relocated to lower-wage regions.

- Rostow's model does not apply to the Asian and the African countries as events in these countries are not justified in any stage of his model.

- The stages are not identifiable properly as the conditions of the take-off and pre take-off stage are very similar and also overlap.

- According to Rostow growth becomes automatic by the time it reaches the maturity stage but Kuznets asserts that no growth can be automatic, there is always a need for a push.

- There appear to be two parallel theories of 'take-off' one is that 'take-off' is a sectoral and non-linear notion, and the other is that it is highly aggregative.[14]

Rostow's thesis is biased towards a western model of modernization, but at the time of Rostow the world's only mature economies were in the west, and no controlled economies were in the "era of high mass-consumption." The model de-emphasizes differences between sectors in capitalistic vs. communistic societies, but seems to innately recognize that modernization can be achieved in different ways in different types of economies.

Another assumption that Rostow took is of trying to fit economic progress into a linear system. This assumption is questioned due to empirical evidence of many countries making 'false starts' then reaching a degree of progress and change and then slipping back. E.g.: In the case of contemporary Russia slipping back from high mass-consumption to a country in transition.

Another criticism of Rostow's work is that it considers large countries with a large population (Japan), with natural resources available at just the right time in its history (Coal in Northern European countries), or with a large land mass (Argentina). He has little to say and indeed offers little hope for small countries, such as Rwanda, which do not have such advantages. Neo-liberal economic theory to Rostow, and many others, does offer hope to much of the world that economic maturity is coming and the age of high mass-consumption is nigh. This does leave a potential "grim meathook future" for the outliers, which do not have the resources, political will, or external backing to become competitive with already developed economies.[15] (See Dependency theory)

See also

References

- Rostow, W. W. (1960). "The Five Stages of Growth-A Summary". The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–16. Archived from the original on 2013-02-23.

- Rostow, W. W. (1971). Politics and the Stages of Growth. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521081979.

- Rostow, W. W. (1962). The Stages of Economic Growth. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 2, 38, 59.

- Mishra, Puri (2010). Economics of Development and Planning—Theory and Practice. Himalaya Publishing House. pp. 127–136. ISBN 978-81-8488-829-4.

- Rostow emphasizes in Stages that "the stages of growth are an arbitrary and limited way of looking at the sequence of modern history: ... to dramatize not merely the uniformities in the sequence of modernization but also—and equally—the uniqueness of each nation's experience."

- "Rostow's Stages of Development vs. Self- Sufficiency". Lewis historical society. 4 January 2011. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Rostow, W. W. (1960). The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 10.

- Brett Wallace (2008-02-02). "IB Geography: Development: Rostow Model". Slideshare.net. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Seligso, Mitchell A. "The Five Stages of Growth W.W. Rostow". Development and Underdevelopment: The Political Economy of Global Inequality: 12.

- Mallick, Oliver Basu (2005). "Rostow's five-stage model of development and ist [sic] relevance in Globalization" (PDF). School of Social Science Faculty of Education and Arts the University of Newcastle. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Stages of Development". Nvcc.edu. 2004-04-22. Archived from the original on 2004-06-18. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- http://albahaegeo.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/rostow_lewis.pdf

- Beckett, Paul A. The Journal of Developing Areas 29.2 (1995): 284-86. Web.

- Itagaki, Yoichi (1963). "Criticism of Rostow's Stage Approach: The Concept of State, System and Type". The Developing Economies. 1 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1049.1963.tb01138.x.

- "Grim Meathook Future" is a quote from new media writer Joshua Ellis"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-03-29. Retrieved 2006-04-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) .

Further reading

- Rostow, W. W. (1959) “The Stages of Economic Growth.” Economic History Review 12#1 1959, pp. 1–16. online

- Rostow, W. W. (1960). The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge University Press.

- Baran, P.; Hobsbawm, E. J. (1961). "The Stages of Economic Growth". Kyklos. 14 (2): 234–242. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.1961.tb02455.x.

- Hunt, Diana (1989). "Rostow of the Stages of Growth". Economic Theories of Development: An Analysis of Competing Paradigms. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 95–101. ISBN 978-0-7450-0237-8.

- Meier, Gerald M. (1989). "Sequence of Stages". Leading Issues in Economic Development (Fifth ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–72. ISBN 978-0-19-505572-6.