Big push model

The big push model is a concept in development economics or welfare economics that emphasizes that a firm's decision whether to industrialize or not depends on its expectation of what other firms will do. It assumes economies of scale and oligopolistic market structure and explains when industrialization would happen.

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

The originator of this theory was Paul Rosenstein-Rodan in 1943. Further contributions were made later on by Murphy, Shleifer and Robert W. Vishny in 1989. Analysis of this economic model ordinarily involves using game theory.

The theory of the model emphasizes that underdeveloped countries require large amounts of investments to embark on the path of economic development from their present state of backwardness. This theory proposes that a 'bit by bit' investment programme will not impact the process of growth as much as is required for developing countries. In fact, injections of small quantities of investments will merely lead to a wastage of resources. Paul Rosenstein-Rodan approvingly quotes a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study in this regard, "There is a minimum level of resources that must be devoted to... a development programme if it is to have any chance of success. Launching a country into self-sustaining growth is a little like getting an airplane off the ground. There is a critical ground speed which must be passed before the craft can become airborne...."[1]

Rosenstein-Rodan argued that the entire industry which is intended to be created should be treated and planned as a massive entity (a firm or trust). He supports this argument by stating that the social marginal product of an investment is always different from its private marginal product, so when a group of industries are planned together according to their social marginal products, the rate of growth of the economy is greater than it would have otherwise been.[2]

The three indivisibilities

According to Rosenstein-Rodan, there exist three indivisibilities in underdeveloped countries. These indivisibilities are responsible for external economies and thus justify the need for a big push. The indivisibilities are as follows-

- Indivisibility in production function

- Indivisibility of demand

- Indivisibility in the supply of savings

Indivisibility in production function

Indivisibilities in the production function may be with respect to any of the following:

These lead to increasing returns (i.e., economies of scale), and may require a high optimum size of a firm. This can be achieved even in developing countries since at least one optimum scale firm can be established in many industries. But investment in social overhead capital comprises investment in all basic industries (like power, transport or communications) which must necessarily come before directly productive investment activities. Investment in social overhead capital is 'lumpy' in nature. Such capital requirements cannot be imported from other nations. Therefore, heavy initial investment necessarily needs to be made in social overhead capital (this is approximated to be about 30 to 40 percent of the total investment undertaken by underdeveloped countries). Social overhead capital is further characterized by four indivisibilities:

- Irreversibility in time: It must precede other directly productive investments

- Minimum durability of equipment:. Any lesser level of durability is either impossible due to technical reasons or much less efficient

- Long gestation periods: The investment in social overhead capital takes time to generate returns and its impact in the economy is not immediately or directly visible

- Irreducible minimum social overhead capital–industry mix: Investment needs to be of a certain minimum magnitude and spread across a mix of industries, without which it will not significantly impact the process of growth.

Indivisibility (or complementarity) of demand

Developing countries are characterized by low per-capita income and purchasing power. Markets in these countries are therefore small. In a closed economy, modernization and increased efficiency in a single industry has no impact on the economy as a whole since the output of that industry will fail to find a market. A large number of industries need to be set up simultaneously so that people employed in one industry consume the output of other industries and thus create complementary demand.

To illustrate this, Rosenstein-Rodan gives the example of a shoe industry. If a country makes large investments in the shoe industry, all the disguisedly employed labor from the other industries find work and a source of income, leading to a rise in production of shoes and their own incomes. This increased income will not be expended only on buying shoes. It is conceivable that the increased incomes will lead to increased spending on other products too. However, there is no corresponding supply of these products to satisfy this increased demand for the other goods. Following the basic market forces of demand and supply, the prices of these commodities will rise. To avoid such a situation, investment must be spread out amongst different industries.

The situation may be different in an open economy as the output of the new industry may replace former imports or possibly find its market by way of exports. But even if the world market acts as a substitute for domestic demand, a big push is still needed (though its required size may now be reduced due to the presence of international trade).

Indivisibility in the supply of savings

High levels of investment require a corresponding high level of savings. We cannot always rely on foreign aid as the huge levels of investments in the different sectors need to be made not only once, but multiple times. Hence domestic savings are a must. But in an underdeveloped economy, this is a challenge due to the low income levels. The marginal rate of savings needs to be increased following the rise in incomes due to higher investment.

How the big push works

Consider a country whose economy is characterized by a large number of sectors which are so small that any increase in the productivity of one sector has no impact on the economy as a whole. Each sector can either rely on traditional methods or switch to modern methods of production which would increase its efficiency. Let us assume that there are workers in the economy and sectors. Each sector therefore has workers.

Using traditional technology, a sector would produce amount of output, with each worker producing one unit of the commodity.

Using modern technology a sector would produce more as the productivity would be greater than one unit per worker. However, a modern sector would require some of the workers (say ) to perform administrative tasks.

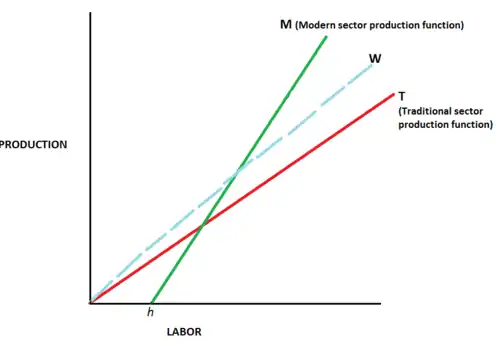

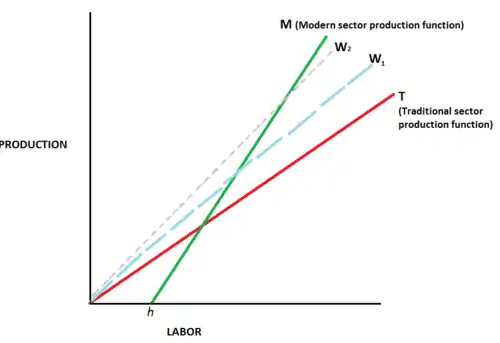

In figure 1, the x-axis represents the labor employed and the y-axis represents the level of production. The production in the traditional sector is given by the curve T and the production in the modern sector is given by M. The curve M has a positive intercept on the x-axis, implying that even with zero production, there is a minimum level of workers who still remain employed for carrying out administrative activities. With our assumption of workers in the economy, the modern sector will have a higher level of productivity than the traditional sector. The production function of the modern sector is steeper than that of the traditional sector because of the higher productivity of workers in the former. The slope of both production functions is , where is the marginal labor required to produce an additional unit of output. This level of is lower for the modern sector than it is for the traditional sector.

Assume that the traditional sector pays workers one unit of output which is subsequently spent equally by them in all sectors. The modern sector pays higher wages to workers. If all the workers are employed by the traditional sector, then the demand generated for the output of each sector is . Government intervention in a manner that investment is carried out on those industries that have higher forward and backward linkages. We have two possible cases:

- Wages are low – When low wages are prevalent in the economy, say , a firm which faces demand will need to employ workers if it wants to modernize. This will cost the firm .

- Now, wages are low. Therefore

- .

- This implies that costs (given by ) are lower than the earnings (given by ). So the firm makes a profit and will choose to modernize (even if other firms do not).

- Wages are high – When high wages are prevalent in the economy, say , a firm which faces demand will make losses if no other firms choose to modernize.

- This is because

- .

- This implies that costs (given by ) are higher than the earnings (given by ).

- However, if all the other firms have modernized, the firm faces a higher demand , arising out of higher income levels of workers of these modernized firms. The firm will hence choose to modernize as well so that it makes profits:

- .

Indivisibilities and external economies

The concept of externalities is relevant for the industrialization of underdeveloped countries, where decisions are to be made regarding distribution of savings among alternative investment opportunities. These arise from the interdependence in market economies.[3]

Pecuniary economies are external economies transmitted through the price system, as prices are the signalling device (under conditions of perfect competition in a market economy). They arise in an industry (say industry X) due to internal economies of overcoming technical indivisibilities. This reduces the price of its product, which will benefit another industry (say industry Y) which use this output as an input or a factor of production.[4] Subsequently, the profits of industry Y will rise, leading to its expansion and generating demand for the output of industry X. As a result, industry X's production and profits also expand.[5]

However in underdeveloped countries, conditions of perfect competition are not present due to the decentralized and differentiated nature of the market. Prices fail to act as a signalling system in the following ways:[3]

- Prices express the situation as it is and do not predict future economic situations

- Prices can decide present productive activities but cannot determine investments which would be appropriate for developing countries

- The response of the private sector to price signals is inadequate and imperfect due to the differentiation and decentralisation in developing countries

This justifies the need for centralized pan-industry planning of investment in developing countries, as the private sector cannot undertake such planning.

Enlargement of the market size is another important externality that arises from the complementarity of industries. There exists an incentive to expand the scale of operations because the employees of one industry become the customers of another industry. In terms of products too (as in the above example of industries X and Y), one industry generates demand for the output of the other when the scale of operations increase.[6]

Marshallian economies also accrue to a firm within a growing industry, resulting from agglomeration of industrial districts or clusters in a particular area. These occur due to the following advantages of agglomeration identified by Alfred Marshall:

- Spillover of information

- Specialization and division of labor

- Development of a market for skilled labor.[5]

Availability of skilled labour is an externality that arises when industrialization occurs, as workers acquire better training and skills. This is not achievable by mere establishment of a few industries, but requires a large program of industrial growth. It is one of the most important external economies because absence of skilled labor is a strong impediment to industrialization.[7]

Role of the state

The large-scale programme of industrialization advocated by this model requires huge investments that are beyond the means of the private sector. The investment in infrastructure and basic industries (like power, transport and communications) is 'lumpy' and has long gestation periods. The role of the state in this theory is therefore critical for investment in social overhead capital. Even if the private sector had the requisite resources to invest in such a programme, it would not do so since it is driven by profit motives.[7] Many investments are profitable in terms of social marginal net product but not in terms of private marginal net product. Due to this, there is no incentive for individual entrepreneurs to invest and take advantage of external economies.[1]

Criticisms

The theory has been criticized by Hla Myint and Celso Furtado, among others, primarily on the grounds of the massive effort required to be taken by underdeveloped countries to move along the path of industrialization. Some of the major criticisms are as follows.

- Difficulties in execution and implementation: The execution of related projects during the course of industrialization may involve unexpected or unavoidable changes due to revisions of plans, delays and deviations from the planned process. Hla Myint notes that the various departments and agencies involved in the process of development need to coordinate closely and evaluate and revise plans continuously. This is a challenging task for the governments of developing countries.[4]

- Lack of absorptive capacity: The implementation of industrialization programmes may be constrained by ineffective disbursement, short-term bottlenecks, macroeconomic problems and volatility, loss of competitiveness and weakening of institutions. Credit is often utilized at low rates or after long time lags. There is often a loss of competitiveness due to the Dutch disease effect.[8]

- Historical inaccuracy: When viewed in light of historical experience of countries over the last two centuries, no country displayed any evidence of development due to massive industrialization programmes. Stationary economies do not develop simply by making large-scale investment in social overhead capital.[9]

- Problems in mixed economies: In a mixed economy, where the private and public sectors co-exist, the environment for growth may not be a conducive one. Unless there is a complementarity between the sectors, there is bound to arise competition between them, with the government departments keeping their plans confidential out of fear of speculative activities by the private sector. The private sector's activities are simultaneously inhibited due to lack of information of government policies and the general economic situation[4]

- Neglect of methods of production: Rather than capital formation, it is productive techniques which determine the success of a country in economic development. The big push model ignores productive techniques in its support for capital formation and industrialisation.[9]

- Shortage of resources in underdeveloped countries: Eugenio Gudin criticizes the theory of the big push on the grounds that underdeveloped countries lack the capital required to provide the big push required for rapid development. If an underdeveloped nation had ample capital supply and scarce factors, it would not be classified as underdeveloped at all. Limited resource availability is the first impediment to such countries. Though this problem may be overcome by foreign aids, industrialization may not take off as expected if the aid flows are volatile.[8]

- Ignores the agricultural sector: With its heavy emphasis on industry, the model finds no place for agriculture. This is a gaping flaw in the theory, as in most underdeveloped countries it is this sector which is large and has labor surplus. Investments in agriculture need to go hand-in-hand with those in industry so as to stimulate the industrial sector by providing a market for industrial goods. If neglected, it would be difficult to meet the food requirements of the nation in the short run and to significantly expand the size of the market in the long run.

- Inflationary pressures: It follows from the neglect of the agricultural sector that food shortages are likely to occur with industrialization. Though it would take time for investments in social overhead capital to yield returns, the demand would increase immediately, thus imposing inflationary pressures on the economy. Cost escalations may even cause projects to be postponed and the development process in general to slow down.[1]

- Dependence on indivisibilities: The emphasis of this theory on indivisibility of processes is too much, as investments need not necessarily be on such a large scale to be economic. Social reforms are ignored, which are vital if a country is to grow on the basis of its own resources and initiatives. Development is bound to intensify if social reform is a part of the industrialization process.[9]

See also

References

- "Notes on the theory of the Big Push", in Howard S. Ellis (ed.) for Latin America, Macmillan & Co., 1961

- Nath, S.K. (June 1962), "The Theory of Balanced Growth",Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 14, No. 2, Oxford University Press, pp. 138–153

- Scitovsky, Tibor (April 1954), "Two Concepts of External Economies" in "The Journal of Political Economy",Vol.62,no.2, Chicago University Press, pp. 143–151

- Myint, Hla (1969), The Economics of the Developing Countries, Hutchinson University Library, p. 119

- A.N. Agarwala, S.P. Singh (1969), The Economics of Underdevelopment, Oxford University Press India, pp. 303–4, ISBN 978-0-19-560674-4

- Meade, James (March 1952), "External Economies and Diseconomies in a Competitive Situation" in "The Economic Journal",Vol.62,no.245, Royal Economic Society, pp. 54–67

- S. K. Misra; V. K. Puri (2010). Economics Of Development And Planning — Theory And Practice (12th ed.). Himalaya Publishing House. pp. 217–222. ISBN 81-8488-829-5.

- Patrick Guillaumont, Sylviane Guillaumont Jeanneney (October 2007), Big Push versus Absorptive Capacity: How to Reconcile the Two Approaches, United Nations University – World Institute for Development Economics Research Discussion Paper No. 2007/05

- Furtado, Celso (1964), "Development and Underdevelopment: A Structural View of the Problems of Developed and Underdeveloped Countries" (translated by Ricardo de Augiar and Eric Charles Drysdale), University of California Press

Further reading

- http://m.domaindlx.com/cihanyuksel2/Two%20Concepts%20of%20External%20Economies.pdf%5B%5D

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120710134938/http://www.colorado.edu/Economics/morey/externalitylit/meade-ej1952.pdf

- http://www.wider.unu.edu/publications/working-papers/discussion-papers/2007/en_GB/dp2007-#

- 05/_files/78515953270128788/default/dp2007-05.pdf

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110813003022/http://www.econometricsociety.org/meetings/wc00/pdf/1269.pdf

- http://www.centrocelsofurtado.org.br/adm/enviadas/doc/25_20060719190655.pdf