Rodrigues starling

The Rodrigues starling (Necropsar rodericanus) is an extinct species of starling that was endemic to the Mascarene island of Rodrigues. Its closest relatives were the Mauritius starling and the hoopoe starling from nearby islands; all three are extinct and appear to be of Southeast Asian origin. The bird was only reported by French sailor Julien Tafforet, who was marooned on the island from 1725 to 1726. Tafforet observed it on the offshore islet of Île Gombrani. Subfossil remains found on the mainland were described in 1879, and were suggested to belong to the bird mentioned by Tafforet. There was much confusion about the bird and its taxonomic relations throughout the 20th century.

| Rodrigues starling | |

|---|---|

| |

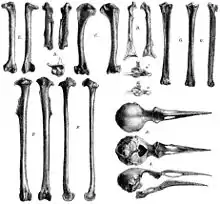

| The lectotype skull and other bones as depicted in the 1879 description | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sturnidae |

| Genus: | †Necropsar Günther & Newton, 1879 vide Slater |

| Species: | †N. rodericanus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Necropsar rodericanus Günther & Newton, 1879 | |

| |

| Location of Rodrigues | |

| Synonyms | |

The Rodrigues starling was 25–30 centimetres (10–12 inches) long, and had a stout beak. It was described as having a white body, partially black wings and tail, and a yellow bill and legs. Little is known about its behaviour. Its diet included eggs and dead tortoises, which it processed with its strong bill. Predation by rats introduced to the area was probably responsible for the bird's extinction some time in the 18th century. It first became extinct on mainland Rodrigues, then on Île Gombrani, its last refuge.

Taxonomy

In 1725, the French sailor Julien Tafforet was marooned on the Mascarene island of Rodrigues for nine months, and his report of his time there was later published as Relation d'île Rodrigue. In the report, he described encounters with various indigenous species, including a white and black bird which fed on eggs and dead tortoises. He stated that it was confined to the offshore islet of Île Gombrani, which was then called au Mât. François Leguat, a Frenchman who was also marooned on Rodrigues from 1691 to 1693 and had written about several species there (his account was published in 1708), did not have a boat, and therefore could not explore the various islets as Tafforet did.[2][3] No people who later traveled to the island mentioned the bird.[4] In an article written in 1875, the British ornithologist Alfred Newton attempted to identify the bird from Tafforet's description, and hypothesised that it was related to the extinct hoopoe starling (Fregilupus varius), which formerly inhabited nearby Réunion.[5]

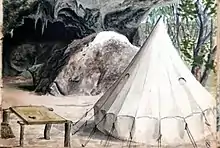

Subfossil bones of a starling-like bird were first discovered on Rodrigues by the police magistrate George Jenner In 1866 and 1871, and by the British naturalist Henry H. Slater in 1874. They were found in caves on the Plaine Coral, a limestone plain in south-west Rodrigues.[6] These bones included the cranium, mandible, sternum, coracoid, humerus, metacarpus, ulna, femur, tibia, and metatarsus of several birds; the bones were deposited in the British Museum and the Cambridge Museum. In 1879, the bones became the basis of a scientific description of the bird by ornithologists Albert Günther and Edward Newton (the brother of Alfred).[7] They named the bird Necropsar rodericanus; Nekros and psar are Greek for "dead" and "starling", while rodericanus refers to the island of Rodrigues. This binomial was originally proposed by Slater in an 1874 manuscript he sent to Günther and Newton.[8] Slater had prepared the manuscript for an 1879 publication, which was never released, but Günther and Newton quoted Slater's unpublished notes in their own 1879 article, and credited him for the name.[6] BirdLife International credits Slater rather than Günther and Newton for the name.[1] Günther and Newton determined that the Rodrigues starling was closely related to the hoopoe starling, and they only kept it in a separate genus due to what they termed "present ornithological practice". Due to the strongly built bill, they considered the new species likely the same as the bird mentioned in Tafforet's account.[7]

In 1900, the English scientist George Ernest Shelley used the spelling Necrospa in a book, thereby creating a junior synonym; he attributed the name to zoologist Philip Sclater.[9] In 1967, the American ornithologist James Greenway suggested that the Rodrigues starling should belong in the same genus as the hoopoe starling, Fregilupus, due to the similarity of the species.[10] More subfossils found in 1974 added support to the claim that the Rodrigues bird was a distinct genus of starling.[11] The stouter bill is mainly what warrants generic separation from Fregilupus.[2] In 2014, the British palaeontologist Julian P. Hume described a new extinct species, the Mauritius starling (Cryptopsar ischyrhynchus), based on subfossils from Mauritius. It was shown to be closer to the Rodrigues starling than to the hoopoe starling, due to the features of its skull, sternum and humerus.[12] Until then, the Rodrigues starling was the only Mascarene passerine bird named from fossil material.[13] Hume noted that Günther and Newton had not designated a holotype specimen among the fossils they based the specific name on, and chose the skull from their syntype series of bones as the lectotype; specimen NMHUK A9050, housed at the Natural History Museum, London. Hume also identified other bones depicted by Günther and Newton among museum collections, and designated them as paralectotypes.[12]

In 1898, the British naturalist Henry Ogg Forbes described a second species of Necropsar, N. leguati, based on a skin in the World Museum Liverpool, specimen D.1792, which was labelled as coming from Madagascar. He suggested that this was the bird mentioned by Tafforet, instead of N. rodericanus from mainland Rodrigues.[14] Walter Rothschild believed the Liverpool specimen to be an albinistic specimen of a Necropsar species supposedly from Mauritius.[15] In 1953, Japanese writer Masauji Hachisuka suggested that N. leguati was distinct enough to warrant its own genus, Orphanopsar.[16] In a 2005 DNA analysis, the specimen was eventually identified as an albinistic specimen of the grey trembler (Cinclocerthia gutturalis) from Martinique.[17]

Hachisuka believed the carnivorous habits described by Tafforet to be unlikely for a starling, and thought the lack of a crest suggested that it was not closely related to Fregilupus. He was reminded of corvids because of the black-and-white plumage, and assumed the bird seen by Tafforet was a sort of chough. In 1937, he named it Testudophaga bicolor, with Testudophaga meaning "tortoise eater", and coined the common name "bi-coloured chough".[18] Hachisuka's assumptions are disregarded today, and modern ornithologists find Tafforet's bird to be identical to the one described from subfossil remains.[6][17][19]

In 1987, the British ornithologist Graham S. Cowles prepared a manuscript that described a new species of Old World babbler, Rodriguites microcarina, based on an incomplete sternum found in a cave on Rodrigues. In 1989, the name was mistakenly published before the description, making it a nomen nudum. Later examination of the sternum by Hume showed that Rodriguites microcarina was identical to the Rodrigues starling.[6]

Evolution

In 1943, the American ornithologist Dean Amadon suggested that Sturnus-like species could have arrived in Africa, and given rise to the wattled starling (Creatophora cinerea) and the Mascarene starlings. According to Amadon, the Rodrigues and hoopoe starlings were related to Asiatic starlings, such as some species of Sturnus, rather than the glossy starlings (Lamprotornis) of Africa and the Madagascan starling (Saroglossa aurata); he concluded this based on the colouration of the birds.[20][21] A 2008 study, which analysed the DNA of various starlings, confirmed that the hoopoe starling was a starling, but with no close relatives among the sampled species.[22]

Extant East Asian starlings, such as the Bali myna (Leucopsar rothschildi) and the white-headed starling (Sturnia erythropygia), have similarities with these extinct species in colouration and other features. As the Rodrigues and Mauritius starlings seem to be more closely related to each other than to the hoopoe starling, which appears to be closer to Southeast Asian starlings, there may have been two separate colonisations of starlings in the Mascarenes from Asia, with the hoopoe starling being the latest arrival. Apart from Madagascar, the Mascarenes were the only islands in the south-west Indian Ocean that contained native starlings. This is probably due to the isolation, varied topography and vegetation of these islands.[12]

Description

The Rodrigues starling was large for a starling, being 25–30 cm (10–12 in) in length. Its body was white or greyish white, with blackish-brown wings, and a yellow bill and legs.[2] Tafforet's complete description of the bird reads as follows:

A little bird is found which is not common, for it is not found on the mainland. One sees it on the islet au Mât [Ile Gombrani], which is to the south of the main island, and I believe it keeps to that islet on account of the birds of prey which are on the mainland, as also to feed with more facility on the eggs of the fishing birds which feed there, for they feed on nothing else but eggs or turtles dead of hunger, which they well know how to tear out of their shells. These birds are a little larger than a blackbird [Réunion bulbul (Hypsipetes borbonicus)], and have white plumage, part of the wings and tail black, the beak yellow as well as the feet, and make a wonderful warbling. I say a warbling, since they have many and altogether different notes. We brought up some with cooked meat, cut up very small, which they eat in preference to seed.[lower-alpha 1][2][23]

Tafforet was familiar with the fauna of Réunion, where the related hoopoe starling lived. He made several comparisons between the faunas of different locations, so the fact that he did not mention a crest on the Rodrigues starling indicates that it was absent. His description of their colouration is similar.[6]

The skull of the Rodrigues starling was similar to and about the same size as that of the hoopoe starling, but the skeleton was smaller. Though the Rodrigues starling was clearly able to fly, its sternum was smaller compared to that of other starlings; it may not have required powerful flight, due to the small area and topography of Rodrigues. The two starlings differed mainly in details of the skull, jaws, and sternum. The maxilla of the Rodrigues starling was shorter, less curved, had a less slender tip, and had a stouter mandible.[6] Not enough remains of the Rodrigues starling have been found to assess whether it was sexually dimorphic.[10] Subfossils show a disparity in size between specimens, but this may be due to individual variation, as the differences are gradual, with no distinct size classes. There is a difference in bill length and shape between two Rodrigues starling specimens, which could indicate dimorphism.[6]

Compared to the other Mascarene starlings, the skull of the Rodrigues starling was relatively compressed from top to bottom, and it had a wide frontal bone. The skull was shaped somewhat differently and longer than that of the hoopoe starling, being about 29 mm (1.1 in) long from the occipital condyle; it was also narrower, being 21–22 mm (0.83–0.87 in) wide. The eyes were set slightly lower, and the upper rims of the eye sockets were about 8 mm (0.31 in) apart. The interorbital septum was more delicate, with a larger hole in its centre. The bill was about 36–39 mm (1.4–1.5 in) long, less curved and proportionally a little deeper than in the hoopoe starling. The rostrum (bony beak) of the upper jaw was long and relatively wide, and the premaxilla (the frontmost bone of the upper jaw) was robust and relatively straight. The bony nasal openings were large and oval, measuring 12–13 mm (0.47–0.51 in) in length. The rostrum of the lower mandible was wide and sharp, and relatively deep and robust at the back, wih a robust retroarticular process (the hind part that connected with the skull) that was directed towards the midline. The mandible was about 52–60 mm (2.0–2.4 in) long and 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in) deep at the back. The supraoccipital ridge on the skull was quite strongly developed, and a biventer muscle attachment in the parietal region below it was conspicuous. This indicates that the starling had strong neck and jaw muscles.[7][6]

The coracoid of the Rodrigues starling was small, relatively gracile, and was otherwise identical to that of the hoopoe starling, measuring 27.5 mm (1.08 in). The keel of the sternum (breast-bone) was similar to that of the hoopoe starling, though the front part was 1 mm lower. The wing and leg bones did not differ much from those of the hoopoe starling and other starlings; the length of the forearm of the hoopoe starling was somewhat longer relatively to the humerus than that of the Rodrigues starling, while other measurements were roughly the same. The humerus was gracile and had a curved shaft, and measured 32–35 mm (1.3–1.4 in). The ulna was small, relatively gracile, and had distinct quill knobs (where the secondary remige feathers attached). The ulna was somewhat shorter than that of the hoopoe starling, measuring 37–40 mm (1.5–1.6 in). The carpometacarpus was small, and measured 22.5 mm (0.89 in). The femur (thigh-bone) was large and robust, particularly ant the upper and lower ends, and it shaft was straight and expanded at the upper end. The femur measured around 33 mm (1.3 in). The tibiotarsus (lower leg bone) was large, robust, with a broad and expanded shaft, and was 52–59 mm (2.0–2.3 in) long. The tarsometatarsus (ankle bone) was long, robust, with a relatively straight shaft, and measured 36–41 mm (1.4–1.6 in).[7][6]

Behaviour and ecology

Little is known about the behaviour of the Rodrigues starling, apart from Tafforet's description, from which various inferences can be made. The robustness of its limbs and the strong jaws with the ability to gape indicates that it foraged on the ground. Its diet may have consisted of the various snails and invertebrates of Rodrigues, as well as scavenged items.[2] Rodrigues had large colonies of seabirds and now-extinct Cylindraspis land tortoises, as well as marine turtles, which would have provided a large amount of food for the starling, particularly during the breeding seasons. Tafforet reported that the pigeons and parrots on the offshore southern islets only came to the mainland to drink water, and Leguat noted that the pigeons only bred on the islets due to persecution from rats on the mainland; the starling may have also done this. Originally, the Rodrigues starling may have been widely distributed on Rodrigues, with seasonal visits to the islets. Tafforet's description also indicates that it had a complex song.[6]

The stouter build and more bent shape of the mandible suggest that the Rodrigues starling used greater force than the hoopoe starling when searching and perhaps digging for food. It probably also had the ability to remove objects and forcefully open entrances when searching for food; it did this by inserting its wedge-shaped bill and opening its mandibles, as other starlings and crows do. This ability supports Tafforet's observation that the bird fed on eggs and dead tortoises.[7] It could have torn dead, presumably juvenile, turtles and tortoises out of their shells. Tafforet did not see any Rodrigues starlings on the mainland, but he stated that they could easily be reared by feeding them meat, which indicates that he brought young birds from a breeding population on Île Gombrani.[2] Tafforet was marooned on Rodrigues during the summer and was apparently able to procure juvenile individuals; some other Rodrigues birds are known to breed at this time, so it is likely that the starling did the same.[6]

Many other species endemic to Rodrigues became extinct after humans arrived, and the island's ecosystem is now heavily damaged. Before humans arrived, forests completely covered the island, but very little remains today. The Rodrigues starling lived alongside other recently extinct birds, such as the Rodrigues solitaire, the Rodrigues parrot, Newton's parakeet, the Rodrigues rail, the Rodrigues owl, the Rodrigues night heron, and the Rodrigues pigeon. Extinct reptiles include the domed Rodrigues giant tortoise, the saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise, and the Rodrigues day gecko.[24]

Extinction

Leguat mentioned that pigeons only bred on islets off Rodrigues, due to predation from rats on the mainland. This may be the reason why Tafforet only observed the Rodrigues starling on an islet. By Tafforet's visit in 1726, the bird must have either been absent or very rare on mainland Rodrigues. Rats - constituting an Invasive species - could have arrived in 1601, when a Dutch fleet surveyed Rodrigues. The islets would have been the last refuge for the bird, until the rats colonised them, too. The Rodrigues starling was extinct by the time French scientist Alexandre Guy Pingré visited Rodrigues during the French 1761 Transit of Venus expedition.[2]

The large populations of tortoises and marine turtles on Rodrigues resulted in the export of thousands of animals, and cats were introduced to control the rats, but the cats attacked the native birds and tortoises as well. The Rodrigues starling was already extinct on the mainland by this time. Rats are adept at crossing water, and inhabit almost all islets off Rodrigues today. At least five species of Aplonis starlings have become extinct in islands of the Pacific Ocean, and rats also contributed to their demise.[12]

Notes

- Tafforet's original French description is as follows: "On trouve un petit oiseau qui n'est pas fort commun, car il ne se trouve pas sur la grande terre; on en vout sur l'île au Mât, qui est au sud de la grande terre, et je crois qu'il se tient sur cette île à cause des oiseaux de proie qui sont à la grande terre, comme aussi pur vivre avec plus de facilité de oefs ou quelques tortues mortes de faim qu'ils savent assez bien déchirer. Ces ouiseaux sont un peu plus gros qu'un merle et ont le plumage blanc, une partie des aîles et de la queue noire, le bec jaune aussi bein que les pattes, et ont un ramage merveillex; je dis un ramage quoiqu'ils en aient plusieurs, et tous différents, et chacun de plus jolis. Nous en avons nourri quelques uns avec de la viande cuite hachée bien menu, qu'ils mangeaient préférablement aux graines de bois."[lower-alpha 2]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Necropsar rodericanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22710836A94263302. Retrieved 24 March 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. London: A & C Black. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- Leguat, F. O. (1891). Oliver, S. P. (ed.). The Voyage of François Leguat of Bresse, to Rodriguez, Mauritius, Java, and the Cape of Good Hope. 1. London: Hakluyt Society. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.46034.

- Fuller, E. (2001). Extinct Birds (revised ed.). New York: Comstock. pp. 366–367. ISBN 978-0-8014-3954-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newton, A. (1875). "Additional Evidence as to the Original Fauna of Rodriguez". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1875: 39–43.

- Hume, J. P. (2014). pp. 44–51.

- Günther, A.; Newton, E. (1879). "The extinct birds of Rodriguez". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 168: 423–437. Bibcode:1879RSPT..168..423G. doi:10.1098/rstl.1879.0043.

- Hume, J. P.; Steel, L.; André, A. A.; Meunier, A. (2014). "In the footsteps of the bone collectors: Nineteenth-century cave exploration on Rodrigues Island, Indian Ocean". Historical Biology. 27 (2): 1. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.886203. S2CID 128901896.

- Shelley, G. E. (1900). The birds of Africa comprising all the species which occur in the Ethiopian region. London: R.H. Porter. p. 342.

- Greenway, J. C. (1967). Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World. New York: American Committee for International Wild Life Protection. pp. 129–132. ISBN 978-0-486-21869-4.

- Cowles, G. S. (1987). "The fossil record". In Diamond, A. W. (ed.). Studies of Mascarene Island Birds. Cambridge. pp. 90–100. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511735769.004. ISBN 9780511735769.

- Hume, J. P. (2014). pp. 55–58.

- Hume, J. P. (2005). "Contrasting taphofacies in ocean island settings: the fossil record of Mascarene vertebrates". Proceedings of the International Symposium "Insular Vertebrate Evolution: The Palaeontological Approach". Monografies de la Societat d'Història Natural de les Balears. 12: 129–144.

- Forbes, H. O. (1898). "On an apparently new, and supposed to be extinct, species of bird from the Mascarene Islands, provisionally referred to the genus Necropsar". Bulletin of the Liverpool Museums. 1: 28–35.

- Rothschild, W. (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co. pp. 5–6.

- Hachisuka, M. (1953). The Dodo and Kindred Birds, or, The Extinct Birds of the Mascarene Islands. London: H. F. & G. Witherby.

- Olson, S. L.; Fleischer, R. C.; Fisher, C. T.; Bermingham, E. (2005). "Expunging the 'Mascarene starling' Necropsar leguati: archives, morphology and molecules topple a myth". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 125: 31–42.

- Hachisuka, M. (1937). "Extinct chough from Rodriguez". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 50: 211–213.

- Cheke, A. S. (1987). "An ecological history of the Mascarene Islands, with particular reference to extinctions and introductions of land vertebrates". In Diamond, A. W. (ed.). Studies of Mascarene Island Birds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–89. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511735769.003. ISBN 978-0521113311.

- Amadon, D. (1943). "Genera of starlings and their relationships" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 1247: 1–16.

- Amadon, D. (1956). "Remarks on the starlings, family Sturnidae" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 1803: 1–41.

- Zuccon, D.; Pasquet, E.; Ericson, P. G. P. (2008). "Phylogenetic relationships among Palearctic-Oriental starlings and mynas (genera Sturnus and Acridotheres: Sturnidae)". Zoologica Scripta. 37 (5): 469–481. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2008.00339.x. S2CID 56403448.

- Tafforet, J. (1891). "Relation de l'ile Rodrigue". In Oliver, S. P. (ed.). The Voyage of François Leguat of Bresse, to Rodriguez, Mauritius, Java, and the Cape of Good Hope. 2. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 335.

- Cheke, A. S.; Hume, J. P. (2008). Lost Land of the Dodo: an Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. New Haven and London: T. & A. D. Poyser. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-0-7136-6544-4.

Works cited

- Hume, J. P. (2014). "Systematics, morphology, and ecological history of the Mascarene starlings (Aves: Sturnidae) with the description of a new genus and species from Mauritius" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3849 (1): 1–75. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3849.1.1. PMID 25112426.

External links

Media related to Necropsar rodericanus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Necropsar rodericanus at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Necropsar rodericanus at Wikispecies

Data related to Necropsar rodericanus at Wikispecies