Religion and ritual of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

The study of religion and ritual of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture has provided important insights into the early history of Europe. The Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, which existed in the present-day southeastern European nations of Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine during the Neolithic Age and Copper Age, from approximately 5500 BC to 2750 BC, left behind thousands of settlement ruins containing a wealth of archaeological artifacts attesting to their cultural and technological characteristics.[1] Refer to the main article for a general description of this culture; this article deals with its religious and ritualistic aspects.

| Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (c. 4800 to 3000 BC) |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Related articles |

Some Cucuteni-Trypillia communities have been found that contain a special building located in the center of the settlement, which archaeologists have identified as sacred sanctuaries. Artifacts have been found inside these sanctuaries, some of them having been intentionally buried in the ground within the structure, that are clearly of a religious nature, and have provided insights into some of the beliefs, and perhaps some of the rituals and structure, of the members of this society. Additionally, artifacts of an apparent religious nature have also been found within many domestic Cucuteni-Trypillia homes.

Many of these artifacts are clay figurines or statues. Archaeologists have identified many of these as fetishes or totems, which are believed to be imbued with powers that can help and protect the people who look after them. These Cucuteni-Trypillia figurines have become known popularly as Goddesses, however, this is actually a misnomer from a scientific point of view. There have been so many of these so-called clay Goddesses discovered in Cucuteni-Trypillia sites that many museums in eastern Europe have a sizeable collection of them, and as a result, they have come to represent one of the more readily-identifiable visual markers of this culture to many people.

Archaeological artifacts

As mentioned above, beginning in the Precucuteni III period (circa 4800-4600 BC), special communal sanctuary buildings began to appear in Cucuteni-Trypillia settlements. They continued to exist during the Cucuteni A and Cucuteni A/B (corresponding to Trypillia B) periods (circa 4600-3800 BC), but then for some reason these sanctuaries began to disappear, until in the Cucuteni B (Trypillia C) period (circa 3800-3500 BC) only a few examples have been discovered from archaeological exploration. These sanctuaries were constructed in a monumental style architecture, and included stelae, statues, shrines, and numerous other ceremonial and religious artifacts, sometimes packed in straw inside pottery.[2]

Masculine cross design

Masculine cross design Hourglass design

Hourglass design Masculine bull horn design

Masculine bull horn design Anthropomorphic figure

Anthropomorphic figure Miniature pottery

Miniature pottery

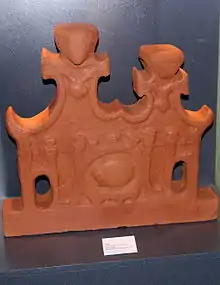

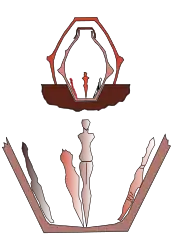

Some of these artifacts originally seemed to represent themes that are Chthonic (of the Underworld), and Celestial/Heavenly, or of the sky. During an excavation in 1973 at the Cucuteni-Trypillia site at Ghelăiești, near the city of Neamț, Romania, archaeologist Ștefan Cucoș discovered a house in the center of the settlement that was the community sanctuary. The following account written by Croatian archeologist Marina Hoti describes the findings within this sanctuary:

In the southeast corner of the house a vase surrounded by six vases was found under the floor. The central vase was turned upside down, covering another vessel with a lid, in which four anthropomorphic figurines were found, arranged in a cross and looking to the four sides of the world. Two figurines were decorated with lines and had completely black heads and legs; the other two were not coloured, but they had traces of ocher red.[3]

Refer to the two accompanying images for a visual depiction of the four figurines within the upturned pot buried in the sanctuary at the Ghelăiești site. Subsequent analysis of this discovery has led to a number of interpretations by various scholars over the years. Ștefan Cucoș, who discovered the artifact, included other symbols discovered at Ghelăiești, including snake-like depictions, the cross-shape of altars, and swastika designs, concluded that it was associated with a ritual of fertility dedicated to the Goddess, associating the black-painted figurines with chthonic themes, and the red ocher-painted figurines with celestial or heavenly themes.[4] Hungarian archaeologist János Makkay also supported a fertility ritual interpretation. Marija Gimbutas, Lithuanian archaeologist and author of "The Civilization of the Goddess", interpreted this discovery as a dualistic interpretation of summer and winter, representing the cycle of life and death in nature.

However, later analysis of this discovery incorporated the entire setting in which these painted figurines were found: specifically, that they were buried under an upturned ceramic vessel. Comparing this find with other similar discoveries from contemporary cultures in Isaiia and Poduri,[5] scholars developed a theory that the tableau taken in its setting, being buried beneath the floor of the sanctuary, and with the four figurines facing outward to the four cardinal directions, represented a means to protect the sanctuary and settlement from evil. The black heads of the figurines were associated with death, and the red ocher was painted on the figurines on the precise body parts that the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture painted on the body parts of their dead before burial. These figurines, therefore, most likely represented departed souls, or beings from the underworld (land of the dead). By enclosing them in an overturned vessel, and burying this entire arrangement under the floor of the sanctuary, they were protecting the settlement from the evil influences these figurines represented by creating a magical sigil of protection.[3]

Mother Goddess figurines

As evidence from archaeology, thousands of artifacts from Neolithic Europe have been discovered, mostly in the form of female figurines. As a result a goddess theory has occurred. The leading historian was Marija Gimbutas, still this interpretation is a subject of great controversy in archaeology due to her many inferences about the symbols on artifacts.[6]

Some researchers consider that the symbols used for representing the feminity are the rhombus for fertility and the triangle as a symbol for fecundity.[7] The cross, symbolizing nature's power of fertility and renewal, was sometimes used to represent masculinity, as well as the phases of the moon.[8]

"Circle of Goddesses" figurines

This ritual assemblies lay in a vase that had a very anomalous shape to the Precucuteni style and were full of soil and straw. The cultic objects were put on display and worshiped during magic-religious ceremonies. The repeated use of them is proven by the presence of some chipping from wear. When not in motion, they were probably stored in this special container. The presence of soil under some statuettes kept in the vase, and the evidence of cariossids on the surface of two figurines and four stools, led some researchers to hypothesize that the pieces had been deposited in soil and straw for magical purposes: they had been left to bud. all the statues were distinct. Some of them bear geometrical decorations. There were observed mature statuettes (that have already given birth), young statuettes (that have not yet given birth), and a babies . Only the mature figurines may sit by right on clay stools.

Bird goddess figurines

According to some researchers as Gimbutas, Lazarocici, for the Precucuteni communities, mythic birds possibly embodied a solar principle and the revival of the life, serving as a symbol of prosperity and protection.

Funerary rites

One of the unanswered questions regarding the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture is the small number of artifacts associated with funerary rites. Although very large settlements have been explored by archaeologists, the evidence for mortuary activity is almost invisible. Making a distinction between the eastern Tripolye and the western Cucuteni regions of the Cucuteni-Trypillia geographical area, American archaeologist Douglass W. Bailey writes:

There are no Cucuteni cemeteries and the Tripolye ones that have been discovered are very late.

[10](p115) The discovery of skulls is more frequent than other parts of the body, however because there has not yet been a comprehensive statistical survey done of all of the skeletal remains discovered at Cucuteni-Trypillia sites, precise post excavation analysis of these discoveries cannot be accurately determined at this time.

Some historians have contrasted the funerary practices of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture with the neighboring Linear Pottery culture, which existed from 5500-4500 BC in the region of present-day Hungary and extending westward into central Europe, making it coincide with the Precucuteni to Cucuteni A Phases. Archaeological evidence from the Linear Pottery sites have shown that they practiced cremation, as well as inhumation (or burial). However, there appears to have been a distinction made in the Linear-Pottery culture on where the bodies were interred, based on gender and social dominance. Women and children were found to be buried beneath the floor of the house, while men were missing, indicating some other practice was associated with how they dealt with the dead bodies of males. One of the conclusions drawn from this evidence was espoused by Marija Gimbutas, author of The Civilization of the Goddess: The world of Old Europe, in which she theorizes that women and children were associated with hearth and home, and so they would be buried beneath it as an act of connecting their bodies to the home.[11]

Collectively taking these characteristics of the neighboring Linear Pottery culture into consideration, scholars have theorized that additional Cucuteni-Tryilian sites may be found, including locations that may be detached from the main settlements, where there may be evidence of the practice of cremation. Archaeologists have discussed broadening the search areas around known Cucuteni-Trypillia settlements to cover a much wider area, and to employ modern techniques to help try to find evidence of outlying sites where evidence of funerary activities could be found.[12]

In addition to cremation and burial, other possible methods of disposing of the bodies of the dead have been suggested. Romanian archaeologists Silvia Marinescu-Bîlcu and Alexandra Bolomey suggest a common practice of abandoning the body to the mercy of Mother Nature,[13](p157) a practice that may be somewhat similar to the Zoroastrian tradition of placing the bodies of the dead on top of a Tower of Silence (or Dakhma), which are then fed upon by carrion birds.

Russian archaeologist Tamara Grigorevna Movsha proposed a theory, in 1960, to explain the absence of some bones, as considered to have magical powers and were scattered on purpose across the settlement.[14]

Others have suggested the practices of cannibalism (known also as anthrophagy), or excarnation, which is the practice of removing the flesh and organs of the dead, leaving only the bones. Romanian archaeologist Sergiu Haimovici writes about such a discovery:

...Alexandra Bolomey...made a review[15] of a series of...human remains, (and) found...at least partly, (that) they have a cultic character and maybe even...an antropophagy [sic] of (a) cultic type.[16]

This would indicate that perhaps some ritualistic cannibalism was practiced among the Cucuteni-Trypillia tribes.

The only conclusion which can be drawn from archeological evidence is that in the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, in the vast majority of cases, the bodies were not formally deposited within the settlement area.[10](p116)

Still in one of few sites, where researchers have found a significant number of human remains (Poduri Dealul Ghindaru in Romania), it seems possible in analyzing the findings, that in the early Cucuteni Culture, the children and infants were inhumed near the houses or even under the house floor.[17]

Cremation

Various researchers have some hypotheses about Cucuteni rituals:

- Incineration Ritual of Cucuteni-Trypillya houses, most probable associated with interment and immolation.

- a ritual, who consider sacrifice buried under houses or on settlement, animals, their heads or parts, possibly associated with immolation ceremony.[18]

- a ritual, who consist in burying (by interment) under dwellings or on settlement of human skulls, bone, sometimes burnt, the deceased with stock, possibly is also associated with immolation.

- Rituals, associated with use of fire, when into pit, exclusive of ashes get the various things, possibly immolation oddments. Also some researchers argue, that in some rituals Cucuteni culture has use anthropomorphous, zoomorphous clay figurines, binocular vessels.[19]

See also

References

- Mallory, James P (1989). In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05052-X. OCLC 246601873.

- Lazarovici, Cornelia-Magda (2005). "Anthropomorphic statuettes from Cucuteni-Trypillian site: some signs and symbols" (PDF). Documenta Praehistorica. Neolitske študije (in English and Slovenian). Ljubljana: Univerza v Ljubljani, Filozofska fakulteta, Oddelek za arheologijo. 32: 145–154. doi:10.4312/dp.32.10. ISSN 1408-967X. OCLC 41553667. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2011.

- Hoti, Marina (December 1993). "Vučedol-Streimov vinograd: magijski ritual i dvojni grob vučedolske kulture" [Vučedol-Streim vineyard: the magical ritual and the twin grave of the Vučedol-Culture]. Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog zavoda (Opvscvla Archaeologica Papers of the Department of Archaeology) (in Croatian and English). 17. Zagreb: Arheoloski institut Sveucilista: 183 to 205. ISSN 0473-0992. OCLC 166882629. Retrieved 5 December 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cucoș, Ștefan (1973). "Un complexe ritual cucutenien découvert a Ghelăiești, dép. Neamț" [A complex Cucutenian ritual discovered at Ghelăiești, Neamț County]. Studii și Cercetări de Istorie Veche (SCIV) (in Romanian). Bucharest: Academia Republici Socialiste Romania. Institutul de arheologie. 24 (2): 207–215. ISSN 0039-4009. OCLC 320530095.

- Marinescu-Bîlcu, Silvia (1974). ""Dansul ritual" în reprezentările plastice neo eneolitice din Moldova" [Neo-plastic representations of Neolithic "Dance ritual" of Moldova]. Studii și Cercetări de Istorie Veche și Arheologie (SCIVA) (in Romanian). Bucharest: Academia Română, Institutul de Arheologie Vasile Pârvan. 25 (2): 167. ISSN 0039-4009. OCLC 183328819.

- Collins, Gloria. "Will the "Great Goddess" resurface?: Reflections in Neolithic Europe". Austin, Texas: University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 12 October 1999. Retrieved 1 December 2009This site was a student brief done for a class assignment.

- Chirica, Vasile (2004). "Teme ale reprezentării "Marii Zeițe" în arta paleolitică și neolitică" [The "Marii Zeițe" theme represented in paleolithic and neolithic art]. Memoria Antiquitatis (in Romanian). Piatra Neamț: Muzeului de Istorie Piatra Neamț. 23: 103–127. ISSN 1222-7528. OCLC 183318963.

- Gimbutas, Marija Alseikaitė (1974), The gods and goddesses of old Europe, 7000 to 3500 BC: myths, legends and cult images, London: Thames & Hudson, p. 303, ISBN 0-500-05014-7, OCLC 979750

- Gimbutas, Marija Alseikaite; Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1999), The Living Goddesses, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 286, ISBN 0-520-21393-9, OCLC 237345793

- Bailey, Douglass W. (2005). Prehistoric figurines: representation and corporeality in the Neolithic. London; New York: Routledge. OCLC 56686499.

- Gimbutas, Marija Alseikaitė (1991), The civilization of the Goddess: the world of Old Europe, San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, ISBN 0-06-250368-5, OCLC 123210574

- Boghian, Dumitru D. (2004), Comunitățile cucuteniene din bazinul Bahluiului (rezumat) [The Cucutenian communities in the bahlui Basin (summary)] (in Romanian, English, and French), translated by Sergiu Ruptaș; Alexandru Dan Boghian; Otilia Ignătescu, Suceava, Romania: Editura Bucovina Istorică şi Editura Universităţii, Universitatea "Ştefan cel Mare" Suceava (Bukovina Publishing House and University Publishing House, The "Ştefan cel Mare" University of Suceava), retrieved 11 December 2009 – This is a summary written by the author of a monograph with the same title, and posted to his online blog Eneoliticul est-carpatic (Eneolithic Eastern Carpathian)

- Marinescu-Bîlcu, Silvia; Bolomey, Alexandra; Cârciumaru, Marin (2000), Drăgușeni: a Cucutenian community, Archaeologia Romanica, 2, Bucharest: Editura Enciclopedică, p. 198, ISBN 973-45-0329-4, OCLC 48400843

- Movsha, Tamara Grigorevna (1960), "К вопросу о трипольских погребениях с обрядом трупоположения" [The issue of Trypillian funeral rite provisions for corpses], Материалы и исследования по археологии Юго-Запада СССР и Румынской Народной Республики [Materials and research in archeology of the southwestern USSR and the Romanian People's Republic], Chişinău: USSR Academy of Sciences, pp. 59–76

- Bolomey, Alexandra (1983). "Noi descoperiri de oase umane într-o așezare Cucuteniană" [New discovery of human bones in a Cucuteni site]. Cercetǎri Arheologice. Colecția Istorie și civilizație (History and Civilization Collection) (in Romanian). Bucharest: Bucuresti Glasul Bucovinei. 6: 159–173. OCLC 224531079.

- Haimovici, Sergiu (2003). Translated by Popa, Monica. "The human bone with possible marks of human teeth found at Liveni site (Cucuteni culture)" (PDF). Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica. Iaşi, Romania: Iaşi University. 9: 97–100. OCLC 224741260. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- "ANATOMICAL DESCRIPTION OF HUMAN REMAINS DISCOVERED IN THE PREHISTORICAL SITE OF CUCUTENI CULTURE AT PODURI-DEALUL GHINDARU (BACĂU COUNTY, ROMANIA)" (PDF). Bio.uaic.ro. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Piatra Neamt permanent exposition

- "THE SACRAL WORLD AND THE MAGIC SPACE". Iananu.kiev.ua. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

External links

- Archaeological Park Cucuteni The website for the multi-institutional and international project entitled "Archaeological Park Cucuteni", which seeks to reconstruct the museum at Cucuteni, Romania, and to more effectively preserve this valuable heritage site (in English and Romanian).

- Cucuteni Culture The French Government's Ministry of Culture's page on Cucuteni Culture (in English).

- Cucuteni Culture The Romanian Dacian Museum page on Cucuteni Culture (in English).

- The Trypillia-USA-Project The Trypillian Civilization Society homepage (in English).

- Трипільська культура в Україні з колекції «Платар» Ukrainian language page about the Ukrainian Platar Collection of Trypillian Culture.

- Trypillian Culture from Ukraine A page from the UK-based group "Arattagar" about Trypillian Culture, which has many great photographs of the group's trip to the Trypillian Museum in Trypillia, Ukraine (in English).

- The Institute of Archaeomythology The homepage for The Institute of Archaeomythology, an international organization of scholars dedicated to fostering an interdisciplinary approach to cultural research with particular emphasis on the beliefs, rituals, social structure and symbolism of ancient societies. Much of their focus covers topics that relate to the Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture (in English).

- The Vădastra Village Project A living history museum in Romania, supported by many international institutions.