Raid on Alexandria

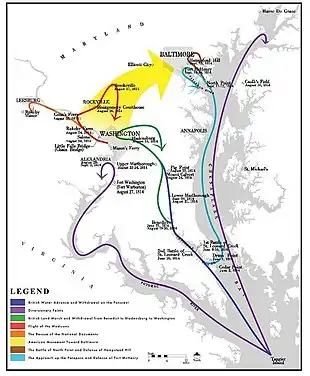

The Raid on Alexandria was a British victory during the War of 1812, which gained much plunder at little cost but may have contributed to the later British repulse at Baltimore by delaying their main forces.

| Raid on Alexandria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

During the War of 1812, British naval forces with little American resistance occupied Alexandria, Virginia, then a part of Washington City and for three days plundered at will until they were ordered to withdraw to prepare for the siege of Baltimore three weeks later. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James Alexander Gordon |

John Rodgers James Monroe Charles Simms | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6 warships | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7 killed 38 wounded[1][2] |

11 killed 19 wounded[1] | ||||||

Background

As part of the British expedition to the Chesapeake Bay in the middle of 1814, a naval force under Commodore James Alexander Gordon was ordered to sail up the Potomac River and attack Fort Washington. The raid was supposed to be a demonstration, to distract American troops from the main British attack on Washington under General Robert Ross.

Fort Washington was located on the Maryland shore, about 8 miles (13 km) below Washington. It was the only fortification on the Potomac River. Although it mounted twelve or fifteen guns (later increased) which commanded the river below its position, the American Brigadier General William H. Winder, commanding the military district around Washington, feared that a determined naval force could nevertheless blast its way past the fort. It would then have Washington at its mercy. A survey the previous year also noted that the fort blockhouse was only able to resist musket fire, and could be destroyed by a cannon as small as a twelve-pounder.[3] Its garrison consisted of 49 men under Captain Samuel T. Dyson of the United States Army's Corps of Artillery and elements of the U.S. 9th and 12th Infantry Regiments.[4]

British advance

Gordon's force consisted of the frigates Seahorse of 38 guns, and Euryalus of 36 guns, the bomb vessels Devastation, Aetna and Meteor, each mounting two large mortars and eight or ten smaller guns and carronades, and the rocket vessel Erebus.[5]

Starting on August 20, Gordon's ships spent several days working over the Kettle Bottom Shoals. Gordon later claimed all his ships grounded twenty times.[6] On August 27, his bomb vessels opened fire on Fort Washington. Captain Dyson, in command of the fort, had been ordered by Brigadier General Winder to demolish the fort only if outflanked and attacked from the rear by large numbers of British troops. Winder also deployed about 500 militia to defend the fort.[7] However, after Gordon had bombarded the fort for two hours,[8] Dyson spiked his own guns, blew up the fort and its magazine containing 3000 pounds of gunpowder and retreated. He was subsequently relieved of command and placed under house arrest. A court martial found him guilty of abandoning his post and destroying government property and he was dismissed from the service.[9]

Gordon's report on the bombardment stated that:

A little before sunset the squadron anchored just out of gunshot; the bomb vessels at once took up their position to cover the frigates in the projected attack at daylight next morning and began throwing shells until about 7:00 pm. The garrison, to our great surprise, retreated from the fort; and a short time afterward Fort Washington was blown up.[9]

Occupation

With the fall of Fort Washington, there was nothing to stop the advance of the British warships on the prosperous port of Alexandria, which lay only a few miles upriver. The town's Common Council had earlier sent a delegation to offer the city's surrender to Rear Admiral George Cockburn, who was occupying Washington.[10] On the morning of 28 August, the Mayor of Alexandria, Charles Simms, was rowed down river under a white flag to ask Gordon for terms for the surrender of the town. It being Sunday, Gordon told Mayor Simms to return to Alexandria and he would bring up his squadron on Monday.

In the subsequent Congressional Investigative Committee report on the burning of the capital and the surrender of Alexandria, the town's clerk, Israel Thompson, submitted the following account:

On the morning of the next day, to wit the 29th of August, [the British squadron] arranged itself along the town, so as to command it from one extremity to the other. The force consisted of two frigates, to wit: the Seahorse, rating thirty-eight guns, and Euryalus, rating thirty-six guns; two rocket ships, of eighteen guns each; two bomb-ships, of eight guns each; and a schooner of two guns, which were but a few hundred yards from the wharves, and the houses so situated that they might have been laid in ashes in a few minutes.

To avoid destruction of the town, the Council agreed to hand over all merchant ships, even those which had been scuttled to prevent them being captured, and merchandise. The British thus acquired twenty-two merchant ships and vast quantities of loot, including flour, cotton, tobacco, wines and cigars.[11]

The delays caused by the shallow water conditions on the Potomac resulted in Gordon's squadron arriving off Fort Washington nearly a week after Ross' troops had entered and left the city of Washington. Having accomplished his primary objective of silencing Fort Washington, and learning that the Capitol and the Washington Navy Yard had been burned a week earlier, Gordon decided not to proceed any further and rejected any suggestion that he take his squadron further up river to burn the docks at Georgetown. His presence in Alexandria nevertheless almost paralysed Washington and the American government, which was trying to reassemble and resume its functions.[12]

British withdrawal

After the British had occupied Alexandria for three days, the Cruizer class brig-sloop Fairy reached Gordon with orders to rejoin the main British fleet in the Chesapeake under Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane.

Gordon began his departure in stages, first sending the bomb-ketch Meteor and the sloop Fairy ahead on September 1, to reconnoiter. The remaining ships departed Alexandria on 2 September, but at White House Point encountered American Militia batteries on the shore.[10] Commodore John Rodgers, with the crews of two frigates under construction (USS Guerriere and Java), twice tried to send fireships against Gordon's ships, but both attempts were foiled by British seamen in the squadron's launches and cutters.

On August 31, Secretary of State James Monroe, in his capacity as acting Secretary of War, ordered an American field artillery battery to be hastily erected on the Virginia shore on the heights of present-day Fort Belvoir. (He had overruled Colonel Decius Wadsworth, who had first gathered the guns, and who resigned rather than take Monroe's orders.)[13] Adverse winds prevented the British ships passing the battery until the winds changed on 5 September.[10] Gordon had his seamen shift the ballast in the bottoms of the ships so that the list to starboard allowed the port side guns to fire higher, and, after unleashing a "fulsome fire", the squadron was finally able to pass the battery in about one hour.[14]

Aftermath

Gordon rejoined Cochrane on September 9. Although, the raid had been very successful in financial terms, the delays caused by the difficult navigation of the Potomac prevented him from supporting the attack on Washington. Cochrane had been forced to wait for Gordon for several days, partly in case Gordon required rescue[15] and also because Gordon's flotilla included most of the available bomb-ketches and rocket vessels in Cochrane's fleet. This delay gave the defenders of Baltimore time to reinforce their defences and allowed them to repulse the British attack on that city.

See also

References

- Whitehorne, p. 153

- "No. 16947". The London Gazette. 27 September 1814. pp. 2082–2083.

- Howard, pp.151-152

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2012). The Encyclopedia of the War of 1812: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 273. ISBN 9781851099573.

- Roosevelt, p.176

- Forester, p.182

- Elting, p.206

- Howard, p.213

- warburton.htm

- white-house-landing.htm

- Elting, p.223

- Elting, pp.224-225

- Elting, pp.223-224

- Herrick (2005) p.168

- Forester, p.183

Sources

- Elting, John, R. Amateurs to Arms, Da Capo Press, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-306-80653-3

- Forester, C. S. The Age of Fighting Sail, New English Library

- George, Christopher T., Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay, Shippensburg, Pa., White Mane, 2001, ISBN 1-57249-276-7

- Herrick, Carloe L. August 24, 1814: Washington in Flames, Falls Church, VA: Higher Education Publications, 2005

- Howard, Hugh (2012). Mr. and Mrs. Madison's War. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-60819-071-3.

- Pitch, Anthony S.The Burning of Washington, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55750-425-3

- Theodore Roosevelt, The Naval War of 1812, Random House, New York, ISBN 0-375-75419-9

- Whitehorne, Joseph A., The Battle for Baltimore 1814, Baltimore: Nautical & Aviation Publishing, 1997, ISBN 1-877853-23-2