Proclamation of Indonesian Independence

The Proclamation of Indonesian Independence (Indonesian: Proklamasi Kemerdekaan Indonesia, or simply Proklamasi) was read at 10:00 in the morning of Friday, 17 August 1945.[1] The declaration marked the start of the diplomatic and armed resistance of the Indonesian National Revolution, fighting against the forces of the Netherlands and pro-Dutch civilians, until the latter officially acknowledged Indonesia's independence in 1949.[2] The document was signed by Sukarno (who signed his name "Soekarno" using the Van Ophuijsen orthography) and Mohammad Hatta, who were appointed president and vice-president respectively the following day.[3][4]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Indonesia |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The date of the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence was made a public holiday by a government decree issued on 18 June 1946.[5]

Background

In 1602, the Dutch established the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and became the dominant European power for almost 200 years. The VOC was dissolved in 1800 following bankruptcy, and the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies as a nationalised colony.[6] The Dutch colonial government was a centralist hierarchical system,[7] where Indonesian representation was limited in the government.[8] Resistance to Dutch rule was met with imprisonment and exile.[9]

The fight for independence from the Netherlands included numerous people, and internal conflicts.[10] It involved an Indonesian youth movement, where the youth were from varying class and educational backgrounds.[11] It included figures such as Chaerul Saleh who was part of Menteng 31, which contained a diverse membership with different educational backgrounds.[12] It also included Kaigun (Wikana) another figure part of the youth movement, who was a student of Sukarno.[13] The fight for independence included a figure in the nationalist movement called Mohammad Hatta who worked to promote Indonesian interests.[14] Another figure in the nationalist movement in Indonesian history was Sukarno, who established the Indonesian National Party in 1927, which advocated for independence from the Dutch.[15] Hatta was educated at a Dutch university[16] and Sukarno studied at the Bandung Institute of Technology where the study group he formed became the Indonesian National Party.[17] Sukarno is known for many famous speeches and advocated for political independence. A speech given in June 1945 by Sukarno ‘Pancasila’ sets out the five principles of the foundation of the nation of Indonesia.[18] In this speech he discusses the importance for political independence, with the first principle being nationalism and also the importance of religion to Indonesia in the principle of a belief in God.[19]

The invasion by the Japanese in Indonesia added a new dynamic for the fight for independence. The Japanese defeated the Dutch in 1942 and moved into Indonesia, and this helped push the Dutch out and assisted towards the proclamation of independence.[8] There were uprisings against the Japanese rule like the Dutch,[20] where farmers and other workers were being exploited by the Japanese. Furthermore, the Japanese had also tried to control Islam.[21] Sukarno discusses in his speeches during the war that he believed independence could be achieved with the assistance of Japan.[22] Hatta also worked with the Japanese, as he wanted to free Indonesian people from the Dutch. Hatta and Sjahrir another figure in the nationalist movement worked together towards independence for Indonesia. Where Hatta worked with the Japanese, Sjahrir focused on establishing an underground support network.[23] Many educated youths influenced by Sjahrir in Jakarta and Bandung started establishing underground support networks for plans of Indonesian independence following Japan's defeat.[24]

The end of the war on August 15 further expedited the process for independence.[15] Youth leaders supported by Sjahrir hoped for a declaration of independence separate from the Japanese, which initially was not supported by Hatta and Sukarno. However, with the assistance of a high ranking Japanese military officer Tadashi Maeda, the declaration of independence was drafted.[25] Sukarno and Hatta on August 17, 1945 proclaimed independence, along with the youth leaders.[26]

Declaration

The draft was prepared only a few hours earlier on the night of 16 August 1945,[1] by Sukarno, Hatta, and Soebardjo, at the house of Rear-Admiral Tadashi Maeda, 1 Miyako-dōri (都通り). The house which is located in Jakarta is now the Formulation of Proclamation Text Museum situated at Jl. Imam Bonjol No. 1. Aside from the three Indonesian leaders and Admiral Maeda, three Japanese agents were also present at the drafting: Tomegoro Yoshizumi (of the Navy Communications Office Kaigun Bukanfu (海軍武官府)); Shigetada Nishijima and Shunkichiro Miyoshi (of the Imperial Japanese Army).[27][28] The original Indonesian Declaration of Independence was typed by Sayuti Melik.[29][30] Maeda himself was sleeping in his room upstairs. He was agreeable to the idea of Indonesia's independence,[31] and had lent his house for the drafting of the declaration. Marshal Terauchi, the highest-ranking Japanese leader in South East Asia and son of former Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake, was however against Indonesia's independence, scheduled for 24 August 1945.[32]

While the formal preparation of the declaration, and the official independence itself for that matter, had been carefully planned a few months earlier, the actual declaration date was brought forward almost inadvertently as a consequence of the Japanese unconditional surrender to the Allies on 15 August 1945.[33] The wording of the proclamation had been discussed at length to balance both conflicting internal Indonesian and Japanese interests, so that it was not worded as formally transferring authority, and would not provoke Indonesian youths into violence. The term ‘TRANSFER OF POWER’ was used in Indonesian to satisfy Japanese interests to appear that it was an administrative transfer of power, although the term used ‘pemindahan kekuasaan’ could be perceived to mean political power. The wording ‘BY CAREFUL MEANS’ related to preventing conflict with members of the youth movement. The wording ‘IN THE SHORTEST POSSIBLE TIME’ was used to meet the needs of all Indonesians for independence.[25][28]

The historic event was triggered by internal conflict between the youth movement and other individuals working towards independence, where Adam Malik suggests a meeting had taken place which discussed proclaiming independence outside of Japan's framework due to Japan's surrender.[34] It included figures from the youth movement such as Chaerul and Wikana, where Wikana in Sukarno's house had encouraged Sukarno to proclaim independence immediately.[35] The declaration was to be signed by the 27 members of the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI) symbolically representing the new nation's diversity.[4] The particular act was apparently inspired by the similar spirit of the United States Declaration of Independence.[36] However, the idea was strongly opposed down by the youth movement, who argued that the committee was too closely associated with the then soon to be defunct Japanese occupation rule, thus creating a potential credibility issue. Instead, members of the youth movement demanded that the signatures of six of them were to be put on the document. All parties involved in the historical moment finally agreed on a compromise solution which only included Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta as the co-signers, 'in the name of the people of Indonesia'.[4]

Initially the proclamation was to be announced at Djakarta central square, but the military had been sent to monitor the area, so the venue was changed to Sukarno's house at Pegangsaan Timur 56. The declaration of independence passed without a hitch.The proclamation was prevented from being broadcast on the radio to the outside world by Yamamoto and Nishimura from the Japanese military, and was also initially prevented from being reported in the newspapers. However Shigetada Nishijima and Tadashi Maeda enabled the proclamation to be dispersed via telephone and telegraph.[4] The proclamation at 56, Jalan Pegangsaan Timur, Jakarta, was heard throughout the country because the text was secretly broadcast by Indonesian radio personnel using the transmitters of the Jakarta Broadcasting Station (ジャカルタ放送局, Jakaruta Hōsōkyoku).The Domei news agency was used to send the text of the proclamation to reach Bandung and Jogjakarta. Members of the youth movement in Bandung facilitated broadcasts of the proclamation in Indonesian and English from radio Bandung. Furthermore, the local radio system was connected with the Central Telegraph Office and it broadcast the proclamation overseas.[37] Moreover, Sukarno's speech that he gave on the day of the proclamation was not fully published.[38] During his speech he discusses the perseverance for the independence of Indonesia under Dutch and Japanese rule, and he states Indonesia being free from any other country.[39]

Draft

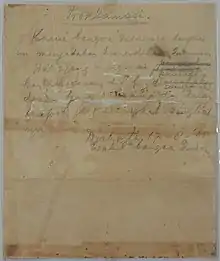

Indonesian

Proklamasi Kami, bangsa Indonesia, dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaan Indonesia.

Hal2 jang mengenai pemindahan kekoeasaan d.l.l., diselenggarakan dengan tjara saksama dan dalam tempoh jang sesingkat-singkatnja

Djakarta, 17-8-'05

Wakil2 Bangsa Indonesia

Initial drafts

Numerous figures who had been involved in the fight for independence had been working on a draft for the proclamation. Hatta had been working on a draft for the proclamation.[40] Furthermore, the youth movement had worked on and prepared a draft, however it was the final draft prepared by Sukarno that was used which balanced the interests of both the Indonesian and Japanese individuals that had been involved.[28]

Final text

P R O K L A M A S I Kami, bangsa Indonesia, dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaan Indonesia.

Hal-hal jang mengenai pemindahan kekoeasaan d.l.l., diselenggarakan dengan tjara saksama dan dalam tempo jang sesingkat-singkatnja.

Djakarta, hari 17 boelan 8 tahoen 05

Atas nama bangsa Indonesia,

Soekarno/Hatta.

The date of the declaration, "05" refers to "Japanese imperial year (皇紀, kōki) 2605".[42]

English translation

An English translation published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as of October 1948 included the entire speech as read by Sukarno. It incorporated remarks made immediately prior to and after the actual proclamation. George McTurnan Kahin, a historian on Indonesia, believed that they were omitted from publication in Indonesia either due to Japanese control of media outlets or fear of provoking a harsh Japanese response.[43]

PROCLAMATION WE THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA HEREBY DECLARE THE INDEPENDENCE OF

INDONESIA. MATTERS WHICH CONCERN THE TRANSFER OF POWER E.T.C.

WILL BE EXECUTED BY CAREFUL MEANS AND IN THE

SHORTEST POSSIBLE TIME.DJAKARTA, 17 AUGUST 05

IN THE NAME OF THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA

SOEKARNO/HATTA

This proclamation is printed on the front of the Rp.100,000 Indonesian banknote of the year 1999 and 2004 series.

Aftermath of the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence

The day after the proclamation, the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence met and elected Sukarno as president and Hatta as vice-president. it also ratified the Constitution of Indonesia.[44] The Dutch, as the former colonial power, viewed the republicans as collaborators with the Japanese, and desired to restore their colonial rule, as they still had political and economic interests in the former Dutch East Indies. The result was a four-year war for Indonesian independence.[45][3] Indonesian youths had played an important role in the proclamation, and they played a central role in the Indonesian National Revolution.[46] One of the other changes that had also taken place during the Japanese occupation included the population in Indonesia undertaking military training. Conflict occurred not only with the Dutch, but also when the Japanese tried to re-establish control in October 1945 in Bandung,[47] and furthermore when the British tried to establish control.[48] After a long struggle for independence, the freedom of Indonesia from the Dutch in 1949 was part of a period of time of decolonization in Asia.[49]

Debate over Dutch recognition of independence date

In 2005, the Netherlands declared that it had decided to accept de facto 17 August 1945 as Indonesia's independence date, which has been interpreted by Indonesian media as an official acceptance of the independence date.[50] However, on 14 September 2011, a Dutch court ruled in the Rawagede massacre case that the Dutch state was responsible because it had the duty to defend its inhabitants, which also indicated that the area was part of the Dutch East Indies, in contradiction of the Indonesian claim of 17 August 1945 as its date of independence.[51] In a 2013 interview the Indonesian historian Sukotjo, among others, asked the Dutch government to formally acknowledge the date of independence as 17 August 1945. [52][53] Before the state visit of King Willem-Alexander (and Queen Máxima) of the Netherlands to Indonesia in 2020, a small group represented by Abdul Halik wrote to him with a few other relatives. As far as they were concerned, the king was not welcome as long as the Netherlands does not legally recognize the Indonesian independence date, 17 August 1945. "We ask for recognition of that date and for apologies. Those who have made mistakes should apologise to those who have suffered."[54] The United Nations recognizes the date of 27 December 1949.[55]

Notes

- Gouda 2002, p. 119.

- Gouda 2002, p. 36.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 344.

- Anderson 1972, p. 83.

- Osman 1953, pp. 621-622.

- Ricklefs 2008, pp. 57,196.

- Booth, Anne (2011). "Splitting, splitting and splitting again: A brief history of the development of regional government in Indonesia since independence". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 167 (1): 33.

- Feith 2006, p. 6.

- Vickers 2013, p. 84.

- Romijn, Peter (2012). "Learning on 'the job': Dutch war volunteers entering the Indonesian war of independence, 1945–46". Journal of Genocide Research. 14 (3–4): 324. doi:10.1080/14623528.2012.719368.

- Anderson 1972, p. 16.

- Anderson 1972, p. 42.

- Anderson 1972, p. 72.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 305.

- Feith, 2006 & pp7-8.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 4.

- Rosyad, Rifki (2007). A quest for true Islam: A Study of the Islamic resurgence movement among the youth in Bandung, Indonesia. Australia: ANU E Press. pp. 1.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 340.

- Nurviyani, Vina; Mulyani, Martina (2016). "The Analysis of Soekarno's Speech on Nation Foundation: Demystifying the Ideology of Pancasila Using Foucauldian Methods". In Ninth International Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 9). Atlantis Press: 123. doi:10.2991/conaplin-16.2017.26. ISBN 9789462523227.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 331.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 333.

- Friend 2014, p. 84.

- Friend 2014, p. 81.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 336.

- Ricklefs 2008, p. 342.

- Vickers 2013, p. 2.

- Isnaeni, Hendri F. (16 August 2015). "Begini Naskah Proklamasi Dirumuskan". historia.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Anderson 1972, p. 82.

- "Former governor Ali Sadikin, freedom fighter SK Trimurti die". Jakarta Post. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- Yuliastuti, Dian (21 May 2008). "Freedom Fighter SK Trimurti Dies". Tempo Interactive. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- Anderson 1972, p. 77.

- Sluimers, Laszlo (1996). "The Japanese military and Indonesian independence". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 27 (1): 34. doi:10.1017/S0022463400010651.

- Anderson 1972, p. 68.

- de Graaf, H. J. (1959). "The Indonesian declaration of independence: 17th of August 1945". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 115 (4): 311. doi:10.1163/22134379-90002230. JSTOR 27860204.

- Anderson 1972, pp. 70-71.

- Gouda 2002, p. 45.

- Anderson 1972, p. 84.

- Kahin 2000, p. 3.

- Kahin 2000, pp. 1-3.

- Anderson 1972, p. 71.

- Mela Arnani (17 August 2020), "Kapan Soekarno Rekaman Suara Pembacaan Teks Proklamasi Indonesia?" [When did Soekarno record the Reading of the Indonesian Proclamation test?], Kompas (in Indonesian), Jakarta, retrieved 27 September 2020

- Poulgrain, Greg (20 August 2015). "Intriguing days ahead of independence". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Kahin 2000, pp. 1-4.

- kahin 1952, p. 138.

- Homan, Gerlof D (1990). "The Netherlands, the United States and the Indonesian Question,1948". Journal of Contemporary History. 25 (1): 124. doi:10.1177/002200949002500106.

- Anderson 1972, p. 1.

- Anderson 1972, p. 140.

- Vickers 2013, p. 102.

- Vickers 2013, p. 3.

- "Dutch govt expresses regrets over killings in RI". Jakarta Post. 18 August 2005. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- "ECLI:NL:RBSGR:2011:BS8793, voorheen LJN BS8793, BY9458, Rechtbank 's-Gravenhage, 354119 / HA ZA 09-4171". 14 September 2011.

- Post, The Jakarta. "Apologize, recognize independence date". The Jakarta Post.

- "Indonesië wil erkenning onafhankelijkheidsdag" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. 8 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- "'Alsof wij er niet toe doen: dat irriteert'". NRC.

- "List of former Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories | The United Nations and Decolonization". www.un.org.

References

- Anderson, Benedict (1972). Java in a Time of Revolution: Occupation and Resistance, 1944–1946. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0687-0.

- Feith, Herbert (2006) [1962]. The decline of constitutional democracy in Indonesia. Singapore: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 9789793780450.

- Friend, Theodore (2014). The blue-eyed enemy: Japan against the West in Java and Luzon, 1942-1945. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Gouda, Frances (2002). American visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US foreign policy and Indonesian nationalism,1920-1949. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Kahin, George McTurnan (1952). Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Kahin, George McT. (2000). "Sukarno's Proclamation of Indonesian Independence" (PDF). Indonesia. 69 (69). doi:10.2307/3351273. hdl:1813/54189. ISSN 0019-7289. JSTOR 3351273.

- Raliby, Osman (1953). Documenta Historica: Sedjarah Dokumenter Dari Pertumbuhan dan Perdjuangan Negara Republik Indonesia (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Bulain-Bintag.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (2008) [1981]. A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300 (4th ed.). London: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-54685-1.

- Vickers, Adrian (2013). A history of modern Indonesia. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9781139447614.