Pre-regulation terraced houses in the United Kingdom

A pre-regulation terraced house is a type of dwelling constructed before Public Health Act 1875. It is a type of British terraced house at the opposite end of the social scale from the aristocratic townhouse, built as cheap accommodation for the urban poor of the Industrial Revolution. The term usually refers to houses built in the century before the 1875 Act, which imposed a duty on local authorities to regulate housing by the use of byelaws. Subsequently, all byelaw terraced housing was required to meet minimum standards of build quality, ventilation, sanitation and population density.[1] Almost all pre-regulation terraced housing has been demolished through successive waves of slum clearance.

History

Between 1801 and 1901 the population increased fourfold, and during this period there was a migration from the land into towns (urbanisation), as the nature of work changed with the Industrial Revolution. Urban population increased tenfold, and there was a need to build houses for the urban worker. Employers built rows of back-to-back and through houses (i.e. those with front and back doors) on the ground available. In older towns they were constrained by the mediaeval street patterns and the need to fit as many houses as possible on the traditional long plots.[3] The poorest lived in single-roomed houses facing onto a communal courtyard with a shared outhouse (privy), a cesspit, a standpipe, and consequently high rates of infant mortality, typhus and cholera.

The urban population influx started in around 1820 as steam or water power was successfully harnessed to drive the machines, and to produce the iron and steel to build the machines. More workers were attracted in from the countryside to tend the machines and a large number of dwellings were required in short order. Water powered mills were built next to rivers and the housing next to the mills in the floodable low-lying ground. The particles from smoke from the steam engines' boilers descended and wrapped the adjacent housing in a layer of grime. The workers were unskilled and poor, so could pay little rent. Although their families were large, they squeezed in lodgers.[4]

The rural migrants preferred employment in the city to the lack of employment where they were born. Accompanying the Industrial Revolution was one in the countryside, as agriculture was mechanised. The medieval system of guaranteed shared land was being replaced by larger farms with tied cottages for fewer employed labourers.

In 1845 there was a further influx of rural immigrants to the city, as penniless migrants fled the Great Famine of Ireland. Seeking work, they too lodged in these houses.[4]

Edwin Chadwick's report on The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842),[5] researched and published at his own expense, highlighted the problems. Action was taken to introduce building control regulations. Specific boards of health were given the power to regulate housing standards in the Public Health Act 1848 and the Local Government Act 1858. These culminated in the Public Health Act 1875.

Public Health Act 1875

In 1875, the Public Health Act was introduced. It required urban authorities to make byelaws for new streets, to ensure structural stability of houses and prevent fires, and to provide for the drainage of buildings and the provision of air-space around buildings.[6] Section 57 determined that all houses must be through houses. Three years later, the Building Act 1878 provided more detail with constructions: it defined foundations, damp proof courses, the thickness of walls, ceiling heights, space between dwellings, under-floor ventilation, ventilation of rooms and size of windows. The Local Government Board, established in 1871, issued the first model bye-laws in 1877/78.[7] Urban authorities either adopted them or wrote their own versions adapted to local conditions. By 1930 when the first slum clearance measures were introduced there was a marked contrast between the residual stock of pre-regulation houses and the newer byelaw houses. The lack of the provisions above had caused the pre-regulation house to physically deteriorate, such that it commanded a far lower rent. It provided accommodation for the very poorest workers; because these houses tended to be closer to the sources of employment, it eliminated the cost of transport.[8]

Design and construction

.jpg.webp)

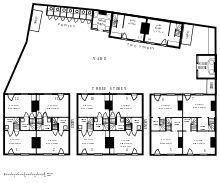

The standard four-roomed two-storey cottage (two-up two-down) at this time measured about 13 feet (4.0 m) by 13 feet (4.0 m), and was built in a terrace behind a house that fronted onto the street. It was reached through a covered passage between the houses, an alleyway as narrow as 2 feet 9 inches (0.84 m)[4] (and known by a variety of regional names).[9] These were the back-dwellings. Alternatively, they were built round a blue brick paved common yard draining to a central channel. All the houses, however many there were, shared a water pump and outhouses (privies). The water was pumped from a well on site, and the privies drained to a deep, regularly emptied, cesspit also on site.

The size of the cottage was important, as the shortage of land and the need to minimise building cost were paramount. Every town approached the situation differently. Liverpool and Birmingham developed a pattern of three-storey back-to-back cottages with a cellar (basement). Nottingham had the reputation for having the smallest houses, while Leicester, whose maximum growth peaked a little later, was less cramped, with through houses and higher ceilings.[10]

Some two-room cottages were as small as 10 feet (3.0 m) by 10 feet (3.0 m). Their narrow steep stairs aligned with the side or back wall. The heating was an open coal-fired cast-iron cooking range in the living room, and maybe a cast-iron 'register grate'[lower-alpha 1] in the bedroom.[10]

Though the ground floor might have had a boarded wooden floor, more likely the cheapest houses would have had flagstones laid on compacted ash, much in the manner of the scullery floor after regulation. This had advantages, but in low-lying districts it would remain permanently damp. The upper floors would have been of wooden planks laid on joists; in poorer houses there were no plastered ceilings. Walls may have been plastered or not. Some houses had a slate damp-proof course but some had none. After poor weather or flooding the walls would dry out only slowly.[7]

Eradication

In general, these houses were unhealthy, shoddy, jerry-built and the rental income achieved was far too low to enable even maintenance never mind improvement. The successive waves of slum clearance such as in Ancoats and Hulme razed the houses, but merely re-located the problem.[12]

References

Footnotes

- A register grate was made principally from a single casting, but it had an openable panel in front of the flue that could regulate the up-draught of air and control the speed of the coal burn and thus the heat.[11]

Notes

- Rosenfeld, Allen & Okoro 2011, p. 258.

- Calow 2007, p. 97.

- Brunskill 2000, p. 186.

- Calow 2007, p. 6.

- Chadwick, Edwin (1842). "Chadwick's Report on Sanitary Conditions". excerpt from Report...from the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain (pp.369–372) (online source). added by Laura Del Col: to The Victorian Web. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Calow 2007, p. 13.

- UWE 2009.

- Calow 2007, pp. 21,22.

- http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2014/10/regional-words-alleyway/

- Calow 2007, p. 8.

- Tyrell-Lewis (2014). "Register grates". Bricks and Brass. Tyrell Lewis. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Parkinson-Bailey 2000, p. 156.

Bibliography

- Brunskill, R.W. (2000). Vernacular architecture : an illustrated handbook (4th ed. (retitled) ed.). London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-19503-9.

- Parkinson-Bailey, John J. (2000). Manchester: an Architectural History. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5606-2.

- Calow, Dennis (2007). Home Sweet Home: A century of Leicester housing 1814-1914. Leicester: University of Leicester:Special collections online. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- Rosenfeld, Orna; Allen, Judith; Okoro, Teri (2011). "RACE, SPACE AND PLACE: LESSONS FROM SHEFFIELD". ACE: Architecture, City and Environment = Arquitectura, Ciudad y Entorno. VI (17): 245–292. ISSN 1886-4805. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- "Evolution of building elements". University of the West of England. 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

Primary source

- "Public Health Act" (PDF). HM Government Stationery Office. 1875. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)