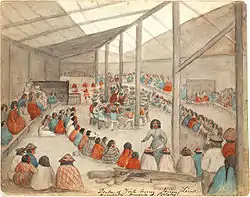

Potlatch

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States,[1] among whom it is traditionally the primary governmental institution, legislative body, and economic system.[2] This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian,[3] Nuu-chah-nulth,[4] Kwakwaka'wakw,[2] and Coast Salish cultures.[5] Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, although mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples (see Athabaskan potlatch).

_a_Kwakwaka'wakw_big_house.jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

A potlatch involves giving away or destroying wealth or valuable items in order to demonstrate a leader's wealth and power. Potlatches are also focused on the reaffirmation of family, clan, and international connections, and the human connection with the supernatural world. Legal proceedings may include namings, business negotiations and transactions, marriages, divorces, deaths, end of mourning, transfers of physical and especially intellectual property, adoptions, initiations, treaty proceedings, monument commemorations, and honouring of the ancestors. Potlatch also serves as a strict resource management regime, where coastal peoples discuss, negotiate, and affirm rights to and uses of specific territories and resources.[6][7][8] Potlatches often involve music, dancing, singing, storytelling, making speeches, and often joking and games. The honouring of the supernatural and the recitation of oral histories are a central part of many potlatches.

Potlatches were historically criminalized by the Government of Canada, with Indigenous nations continuing the tradition underground despite the risk of government reprisals including mandatory jail sentences of at least two months; the practice has been studied by many anthropologists. Since the practice was decriminalized in 1951, the potlatch has re-emerged in some communities. In many it is still the bedrock of Indigenous governance, as in the Haida Nation, which has rooted its democracy in potlatch law.[9][10]

The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning "to give away" or "a gift"; originally from the Nuu-chah-nulth word paɬaˑč, to make a ceremonial gift in a potlatch.[1]

Overview

- N.B. This overview concerns the Kwakwaka'wakw potlatch. Potlatch traditions and formalities and kinship systems in other cultures of the region differ, often substantially.

A potlatch was held on the occasion of births, deaths, adoptions, weddings, and other major events. Typically the potlatch was practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends. The event was hosted by a numaym, or 'House', in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. A numaym was a complex cognatic kin group usually headed by aristocrats, but including commoners and occasional slaves. It had about one hundred members and several would be grouped together into a nation. The House drew its identity from its ancestral founder, usually a mythical animal who descended to earth and removed his animal mask, thus becoming human. The mask became a family heirloom passed from father to son along with the name of the ancestor himself. This made him the leader of the numaym, considered the living incarnation of the founder.[11]:192

Only rich people could host a potlatch. Tribal slaves were not allowed to attend a potlatch as a host or a guest. In some instances, it was possible to have multiple hosts at one potlatch ceremony (although when this occurred the hosts generally tended to be from the same family). If a member of a nation had suffered an injury or indignity, hosting a potlatch could help to heal their tarnished reputation (or "cover his shame", as anthropologist H. G. Barnett worded it).[12] The potlatch was the occasion on which titles associated with masks and other objects were "fastened on" to a new office holder. Two kinds of titles were transferred on these occasions. Firstly, each numaym had a number of named positions of ranked "seats" (which gave them a seat at potlatches) transferred within itself. These ranked titles granted rights to hunting, fishing and berrying territories.[11]:198 Secondly, there were a number of titles that would be passed between numayma, usually to in-laws, which included feast names that gave one a role in the Winter Ceremonial.[11]:194 Aristocrats felt safe giving these titles to their out-marrying daughter's children because this daughter and her children would later be rejoined with her natal numaym and the titles returned with them.[11]:201 Any one individual might have several "seats" which allowed them to sit, in rank order, according to their title, as the host displayed and distributed wealth and made speeches. Besides the transfer of titles at a potlatch, the event was given "weight" by the distribution of other less important objects such as Chilkat blankets, animal skins (later Hudson Bay blankets) and ornamental "coppers". It is the distribution of large numbers of Hudson Bay blankets, and the destruction of valued coppers that first drew government attention (and censure) to the potlatch.[11]:205 On occasion, preserved food was also given as a gift during a potlatch ceremony. Gifts known as sta-bigs consisted of preserved food that was wrapped in a mat or contained in a storage basket.[13]

Dorothy Johansen describes the dynamic: "In the potlatch, the host in effect challenged a guest chieftain to exceed him in his 'power' to give away or to destroy goods. If the guest did not return 100 percent on the gifts received and destroy even more wealth in a bigger and better bonfire, he and his people lost face and so his 'power' was diminished."[14] Hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, were observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods.

Potlatch ceremonies were also used as coming-of-age rituals. When children were born, they would be given their first name at the time of their birth (which was usually associated with the location of their birthplace). About a year later, the child's family would hold a potlatch and give gifts to the guests in attendance on behalf of the child. During this potlatch, the family would give the child their second name. Once the child reached about 12 years of age, they were expected to hold a potlatch of their own by giving out small gifts that they had collected to their family and people, at which point they would be able to receive their third name.[15]

For some cultures, such as Kwakwaka'wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts' genealogy and cultural wealth. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures such as the dzunukwa.

.jpg.webp)

Chief O'wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu'ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas,

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, 'Do as the Indian does'? No, we do not. Why, then, will you ask us, 'Do as the white man does'? It is a strict law that bids us to dance. It is a strict law that bids us to distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you are come to forbid us to dance, begone; if not, you will be welcome to us.[16]

It is important to note the differences and uniqueness among the different cultural groups and nations along the coast. Each nation, community, and sometimes clan has its own way of practicing the potlatch with diverse presentation and meaning. The Tlingit and Kwakiutl nations of the Pacific Northwest, for example, held potlatch ceremonies for different occasions. The Tlingit potlatches occurred for succession (the granting of tribal titles or land) and funerals. The Kwakiutl potlatches, on the other hand, occurred for marriages and incorporating new people into the nation (i.e., the birth of a new member of the nation.)[17] The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for various specific types of gatherings. It is important to keep this variation in mind as most of our detailed knowledge of the potlatch was acquired from the Kwakwaka'wakw around Fort Rupert on Vancouver Island in the period 1849 to 1925, a period of great social transition in which many features became exacerbated in reaction to British colonialism.[11]:188–208

History

Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food (oolichan, or candlefish, oil or dried food), canoes, slaves, and ornamental "coppers" among aristocrats, but not resource-generating assets such as hunting, fishing and berrying territories. Coppers were sheets of beaten copper, shield-like in appearance; they were about two feet long, wider on top, cruciform frame and schematic face on the top half. None of the copper used was ever of Indigenous metal. A copper was considered the equivalent of a slave. They were only ever owned by individual aristocrats, and never by numaym, hence could circulate between groups. Coppers began to be produced in large numbers after the colonization of Vancouver Island in 1849 when war and slavery were ended.[11]:206

The arrival of Europeans resulted in the introduction of numerous diseases against which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, resulting in a massive population decline. Competition for the fixed number of potlatch titles grew as commoners began to seek titles from which they had previously been excluded by making their own remote or dubious claims validated by a potlatch. Aristocrats increased the size of their gifts in order to retain their titles and maintain social hierarchy.[18] This resulted in massive inflation in gifting made possible by the introduction of mass-produced trade goods in the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries. Archaeological evidence for the potlatching ceremony is suggested from the ~1,000 year-old Pickupsticks site in interior Alaska.[19]

Potlatch ban

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 in an amendment to the Indian Act,[20] largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it "a worse than useless custom" that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to 'civilized values' of accumulation.[21] The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was "by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized".[22] Thus in 1884, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the Potlatch and making it illegal to practice. Section 3 of the Act read,

Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the "Potlatch" or the Indian dance known as the "Tamanawas" is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in any gaol or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly, an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.[23]

In 1888, the anthropologist Franz Boas described the potlatch ban as a failure:

The second reason for the discontent among the Indians is a law that was passed, some time ago, forbidding the celebrations of festivals. The so-called potlatch of all these tribes hinders the single families from accumulating wealth. It is the great desire of every chief and even of every man to collect a large amount of property, and then to give a great potlatch, a feast in which all is distributed among his friends, and, if possible, among the neighboring tribes. These feasts are so closely connected with the religious ideas of the natives, and regulate their mode of life to such an extent, that the Christian tribes near Victoria have not given them up. Every present received at a potlatch has to be returned at another potlatch, and a man who would not give his feast in due time would be considered as not paying his debts. Therefore the law is not a good one, and can not be enforced without causing general discontent. Besides, the Government is unable to enforce it. The settlements are so numerous, and the Indian agencies so large, that there is nobody to prevent the Indians doing whatsoever they like.[24]

Eventually the potlatch law, as it became known, was amended to be more inclusive and address technicalities that had led to dismissals of prosecutions by the court. Legislation included guests who participated in the ceremony. The Indigenous people were too large to police and the law too difficult to enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant "the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence".[25] Even so, except in a few small areas, the law was generally perceived as harsh and untenable. Even the Indian agents employed to enforce the legislation considered it unnecessary to prosecute, convinced instead that the potlatch would diminish as younger, educated, and more "advanced" Indians took over from the older Indians, who clung tenaciously to the custom.[26]

Persistence

The potlatch ban was repealed in 1951.[27] Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, Indigenous people now openly hold potlatches to commit to the restoring of their ancestors' ways. Potlatches now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright. Anthropologist Sergei Kan was invited by the Tlingit nation to attend several potlatch ceremonies between 1980 and 1987 and observed several similarities and differences between traditional and contemporary potlatch ceremonies. Kan notes that there was a language gap during the ceremonies between the older members of the nation and the younger members of the nation (age fifty and younger) due to the fact that most of the younger members of the nation do not speak the Tlingit language. Kan also notes that unlike traditional potlatches, contemporary Tlingit potlatches are no longer obligatory, resulting in only about 30% of the adult tribal members opting to participate in the ceremonies that Kan attended between 1980 and 1987. Despite these differences, Kan stated that he believed that many of the essential elements and spirit of the traditional potlatch were still present in the contemporary Tlingit ceremonies.[28]

Anthropological theory

In his book The Gift, the French ethnologist, Marcel Mauss used the term potlatch to refer to a whole set of exchange practices in tribal societies characterized by "total prestations", i.e., a system of gift giving with political, religious, kinship and economic implications.[29] These societies' economies are marked by the competitive exchange of gifts, in which gift-givers seek to out-give their competitors so as to capture important political, kinship and religious roles. Other examples of this "potlatch type" of gift economy include the Kula ring found in the Trobriand Islands.[11]:188–208

See also

- Competitive altruism

- Conspicuous consumption

- Guy Debord, French Situationist writer on the subject of potlatch and commodity reification.

- Izikhothane

- Koha, a similar concept among the Māori

- Kula ring

- List of bibliographical materials on the potlatch

- Moka exchange, a similar concept in Papua New Guinea

- Potluck ("potluck" is the older term in English, but folk etymology has derived the term "potluck" from the Native American custom of potlatch)

- Pow wow, a gathering whose name is derived from the Narragansett word for "spiritual leader"

References

- Harkin, Michael E., 2001, Potlatch in Anthropology, International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes, eds., vol 17, pp. 11885-11889. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Aldona Jonaitis. Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch. University of Washington Press 1991. ISBN 978-0-295-97114-8.

- Seguin, Margaret (1986) "Understanding Tsimshian 'Potlatch.'" In: Native Peoples: The Canadian Experience, ed. by R. Bruce Morrison and C. Roderick Wilson, pp. 473–500. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Atleo, Richard. Tsawalk: A Nuu-chah-nulth Worldview, UBC Press; New Ed edition (February 28, 2005). ISBN 978-0-7748-1085-2

- Matthews, Major J. S. (1955). Conversations with Khahtsahlano 1932–1954. pp. 190, 266, 267. ASIN B0007K39O2. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- Clutesi, George (May 1969). Potlatch (2 ed.). Victoria, BC: The Morriss Printing Company.

- Davidson, Sara Florence (2018). Potlatch as Pedagogy (1 ed.). Winnipeg, Manitoba: Portage and Main. ISBN 978-1-55379-773-9.

- Swanton, John R (1905). Contributions to the Ethnologies of the Haida (2 ed.). New York: EJ Brtill, Leiden, and GE Stechert. ISBN 0-404-58105-6.

- "Constitution of the Haida Nation" (PDF). Council of the Haida Nation. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "Haida Accord" (PDF). Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Graeber, David (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of our own Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

- Barnett, H. G. (1938). "The Nature of the Potlatch". American Anthropologist. 40 (3): 349–358. doi:10.1525/aa.1938.40.3.02a00010.

- Snyder, Sally (April 1975). "Quest for the Sacred in Northern Puget Sound: An Interpretation of Potlatch". Ethnology. 14 (2): 149–161. doi:10.2307/3773086. JSTOR 3773086.

- Dorothy O. Johansen, Empire of the Columbia: A History of the Pacific Northwest, 2nd ed., (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), pp. 7–8.

- McFeat, Tom (1978). Indians of the North Pacific Coast. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 72–80.

- Franz Boas, "The Indians of British Columbia," The Popular Science Monthly, March 1888 (vol. 32), p. 631.

- Rosman, Abraham (1972). "The Potlatch: A Structural Analysis 1". American Anthropologist. 74 (3): 658–671. doi:10.1525/aa.1972.74.3.02a00280.

- (1) Boyd (2) Cole & Chaikin

- Smith, Gerad (2020). Ethnoarchaeology of the Middle Tanana Valley, Alaska. ProQuest.

- An Act further to amend "The Indian Act, 1880," S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3.

- G. M. Sproat, quoted in Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), 15

- Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1977, 207.

- An Act further to amend "The Indian Act, 1880," S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3. Reproduced in n.41, Bell, Catherine (2008). "Recovering from Colonization: Perspectives of Community Members on Protection and Repatriation of Kwakwaka'wakw Cultural Heritage". In Bell, Catherine; Val Napoleon (eds.). First Nations Cultural Heritage and Law: Case Studies, Voices, and Perspectives. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7748-1462-1. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- Franz Boas, "The Indians of British Columbia," The Popular Science Monthly, March 1888 (vol. 32), p. 636.

- Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1991, 159.

- Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), Conclusion

- Gadacz, René R. "Potlatch". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- Kan, Sergei (1989). "Cohorts, Generations, and their Culture: The Tlingit Potlatch in the 1980s". Anthropos: International Review of Anthropology and Linguistics. 84: 405–422.

- Godelier, Maurice (1996). The Enigma of the Gift. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. pp. 147–61.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Potlatch ceremony. |

- U'mista Museum of potlatch artifacts.

- Potlatch An exhibition from the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Oliver S. Van Olinda Photographs A collection of photographs depicting life on Vashon Island, Whidbey Island, Seattle and other communities around Puget Sound, Washington, Photographs of Native American activities such as documentation of a potlatch on Whidbey Island.