Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War

The Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War, or Great War, was a war that occurred between 1409 and 1411 between the Teutonic Knights and the allied Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Inspired by the local Samogitian uprising, the war began with a Teutonic invasion of Poland in August 1409. As neither side was ready for a full-scale war, Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia brokered a nine-month truce.

| Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Lithuanian Crusade | |||||||

Battle of Grunwald by Jan Matejko (1878) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Vassals of Poland: Vassals of Lithuania: Support: | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

After the truce expired in June 1410, the military-religious monks were decisively defeated in the Battle of Grunwald, one of the largest battles in medieval Europe. Most of the Teutonic leadership was killed or taken prisoner. Although they were defeated, the Teutonic Knights withstood the siege on their capital in Marienburg (Malbork) and suffered only minimal territorial losses in the Peace of Thorn (1411). Territorial disputes lasted until the Peace of Melno of 1422.

However, the Knights never recovered their former power, and the financial burden of war reparations caused internal conflicts and economic decline in their lands. The war shifted the balance of power in Central Europe and marked the rise of the Polish–Lithuanian union as the dominant power in the region.[1]

Historical background

In 1230, the Teutonic Knights, a crusading military order, moved to the Kulmerland (today within the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship) and, upon the request of Konrad I, king of the Masovian Slavs, launched the Prussian Crusade against the pagan Prussian clans. With support from the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor, the Teutons conquered and converted the Prussians by the 1280s and shifted their attention to the pagan Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For about a hundred years the Knights fought the Lithuanian Crusade raiding the Lithuanian lands, particularly Samogitia as it separated the Knights in Prussia from their branch in Livonia. The border regions became uninhabited wilderness, but the Knights gained very little territory. The Lithuanians first gave up Samogitia during the Lithuanian Civil War (1381–84) in the Treaty of Dubysa. The territory was used as a bargaining chip to ensure Teutonic support for one of the sides in the internal power struggle.

In 1385, Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania proposed to marry reigning Queen Jadwiga of Poland in the Union of Kreva. Jogaila converted to Christianity and was crowned as the King of Poland thus creating a personal union between the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The official Lithuanian conversion to Christianity removed the religious rationale for the Order's activities in the area.[2] However the Knights responded by publicly contesting the sincerity of Jogaila's conversion, bringing the charge to a papal court.[2] The territorial disputes continued over Samogitia, which was in Teutonic hands since the Peace of Raciąż of 1404. Poland also had territorial claims against the Knights in Dobrzyń Land and Danzig (Gdańsk), but the two states were largely at peace since the Treaty of Kalisz (1343).[3] The conflict was also motivated by trade considerations: the Knights controlled lower reaches of the three largest rivers (Neman, Vistula and Daugava) in Poland and Lithuania.[4]

Course of war

Uprising, war and truce

In May 1409, an uprising in Teutonic-held Samogitia started. Lithuania supported the uprising and the Knights threatened to invade. Poland announced its support for the Lithuanian cause and threatened to invade Prussia in return. As Prussian troops evacuated Samogitia, the Teutonic Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen declared war on the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania on 6 August 1409.[5] The Knights hoped to defeat Poland and Lithuania separately and began by invading Greater Poland and Kuyavia, catching the Poles by surprise.[6] The Knights burned the castle at Dobrin (Dobrzyń nad Wisłą), captured Bobrowniki after a fourteen-day siege, conquered Bydgoszcz (Bromberg), and sacked several towns.[7] The Poles organized counterattacks and recaptured Bydgoszcz.[8] The Samogitians attacked Memel (Klaipėda).[6] However, neither side was ready for a full-scale war.

Wenceslaus, King of the Romans, agreed to mediate the dispute. A truce was signed on 8 October 1409; it was set to expire on 24 June 1410.[9] Both sides used this time for preparations for the battle, gathering the troops and engaging in diplomatic maneuvers. Both sides sent letters and envoys accusing each other of various wrongdoings and threats to Christendom. Wenceslaus, who received a gift of 60,000 florins from the Knights, declared that Samogitia rightfully belonged to the Knights and only Dobrzyń Land should be returned to Poland.[10] The Knights also paid 300,000 ducats to Sigismund of Hungary, who had ambitions for the principality of Moldova, for his military assistance.[10] Sigismund attempted to break the Polish–Lithuanian alliance by offering Vytautas a king's crown; Vytautas's acceptance of such a crown would violate the terms of the Ostrów Agreement and create Polish-Lithuanian discord.[11] At the same time Vytautas managed to obtain a truce from the Livonian Order.[12]

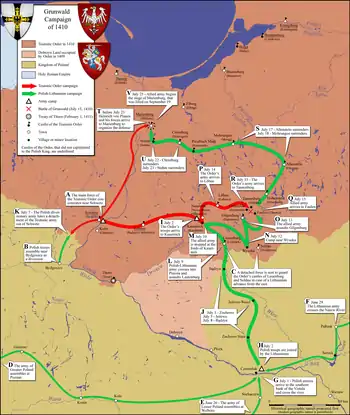

Strategy and march in Prussia

By December 1409, Jogaila and Vytautas had agreed on a common strategy: their armies would unite into a single massive force and march together towards Marienburg (Malbork), capital of the Teutonic Knights.[13] The Knights, who took a defensive position, did not expect a joint attack and were preparing for a dual invasion – by the Poles along the Vistula River towards Danzig (Gdańsk) and by the Lithuanians along the Neman River towards Ragnit (Neman).[14] To counter this perceived threat, Ulrich von Jungingen concentrated his forces in Schwetz (Świecie), a central location from where troops could respond to an invasion from any direction rather quickly.[15] To keep the plans secret and misguide the Knights, Jogaila and Vytautas organised several raids into border territories, thus forcing the Knights to keep their troops in place.[13]

The first stage of the Grunwald campaign was gathering all Polish–Lithuanian troops at Czerwinsk, a designated meeting point about 80 km (50 mi) from the Prussian border, where the joint army crossed the Vistula over a pontoon bridge.[16] This maneuver, which required precision and intense coordination among multi-ethnic forces, was accomplished in about a week from 24 to 30 June 1410.[14] After the crossing, Masovian troops under Siemowit IV and Janusz I joined the Polish–Lithuanian army.[14] The massive force began its march north towards Marienburg (Malbork), capital of Prussia, on 3 July. The Prussian border was crossed on 9 July.[16] As soon as Ulrich von Jungingen grasped Polish–Lithuanian intentions, he left 3,000 men at Schwetz (Świecie) under Heinrich von Plauen[17] and marched the main forces to organise a line of defence on the Drewenz River (Drwęca) near Kauernik (Kurzętnik).[18] On 11 July, Jogaila decided against crossing the river at such a strong defensible position. The army would instead bypass the river crossing by turning east, towards its sources, where no other major rivers separated his army from Marienburg.[18] The Teutonic army followed the Drewenz River north, crossed it near Löbau (Lubawa), and then moved east in parallel with the Polish–Lithuanian army. The latter ravaged the village of Gilgenburg (Dąbrówno).[19] Von Jungingen was so enraged by the atrocities that he swore to defeat the invaders in battle.[20]

Battle of Grunwald

The Battle of Grunwald took place on 15 July 1410 between the villages of Grunwald, Tannenberg (Stębark) and Ludwigsdorf (Łodwigowo).[21] Modern estimates of number of troops involved range from 16,500 to 39,000 Polish–Lithuanian and 11,000 to 27,000 Teutonic men.[22] The Polish–Lithuanian army was an amalgam of nationalities and religions: the Roman Catholic Polish–Lithuanian troops fought side by side with pagan Samogitians, Eastern Orthodox Ruthenians, and Muslim Tatars. Twenty-two different peoples, mostly Germanic, joined the Teutonic side.[23]

The Knights hoped to provoke Poles or Lithuanians to attack first and sent two swords, known as Grunwald Swords, to "assist Jogaila and Vytautas in battle".[24] Lithuanians attacked first, but after more than an hour of heavy fighting, the Lithuanian light cavalry started a full retreat.[25] The reason for the retreat – whether it was a retreat of the defeated force or a preconceived maneuver – remains a topic of academic debate.[26] Heavy fighting began between Polish and Teutonic forces and even reached the royal camp of Jogaila. One Knight charged directly against King Jogaila, who was saved by royal secretary Zbigniew Oleśnicki.[2] As Polish units were gaining the upper hand, the Lithuanians returned to the battle. As Grand Master von Jungingen attempted to break through the Lithuanian lines, he was killed.[27] Surrounded and leaderless, the Teutonic Knights began to retreat towards their camp in hopes to organize a defensive wagon fort. However, the defense was soon broken and the camp was ravaged and according to an eyewitness account, more Knights died there than in the battlefield.[28]

The defeat of the Teutonic Knights was resounding. About 8,000 Teuton soldiers were killed[29] and an additional 14,000 were taken captive.[30] Most of the brothers of the Order were killed, including most of the Teutonic leadership. The highest-ranking Teutonic official to escape the battle was Werner von Tettinger, Komtur of Elbing (Elbląg).[30] Most of the captive commoners and mercenaries were released shortly after the battle on condition that they report to Kraków on 11 November 1410.[31] The nobles were kept in captivity and high ransoms were demanded for each.

Siege of Marienburg

After the battle, the Polish and Lithuanian forces delayed their attack on the Teutonic capital in Marienburg (Malbork) by staying on the battlefield for three days and then marching an average of only about 15 km (9.3 mi) per day.[32] The main forces did not reach heavily fortified Marienburg until 26 July. This delay gave Heinrich von Plauen enough time to organize a defense. Polish historian Paweł Jasienica speculated that this was likely an intentional move by Jagiełło, who together with Vytautas preferred to keep the humbled but not decimated Order in play as to not upset the balance of power between Poland (which would most likely acquire most of the Order possessions if it was totally defeated) and Lithuania; but a lack of primary sources precludes a definitive explanation.[33]

Jogaila, meanwhile, also sent his troops to other Teutonic fortresses, which often surrendered without resistance,[34] including the major cities of Danzig (Gdańsk), Thorn (Toruń), and Elbing (Elbląg).[35] Only eight castles remained in Teutonic hands.[36] The Polish and Lithuanian besiegers of Marienburg were not prepared for a long-term engagement, suffering from lack of ammunition, low morale, and an epidemic of dysentery.[37] The Knights appealed to their allies for help and Sigismund of Hungary, Wenceslaus, King of the Romans, and the Livonian Order promised financial aid and reinforcements.[38] The siege of Marienburg was lifted on 19 September. The Polish–Lithuanian forces left garrisons in fortresses that were captured or surrendered and returned home. However, the Knights quickly recaptured most of the castles. By the end of October, only four Teutonic castles along the border remained in Polish hands.[39] Jogaila raised a fresh army and dealt another defeat to the Knights in the Battle of Koronowo on 10 October 1410. Following other brief engagements, both sides agreed to negotiate.

Aftermath

The Peace of Thorn was signed on 1 February 1411. Under its terms, the Knights ceded the Dobrin Land (Dobrzyń Land) to Poland and agreed to resign their claims to Samogitia during the lifetimes of Jogaila and Vytautas,[40] although another two wars (the Hunger War of 1414 and the Gollub War of 1422) would be waged before the Treaty of Melno permanently resolved the territorial disputes.[41] The Poles and Lithuanians were unable to translate the military victory into territorial or diplomatic gains. However, the Peace of Thorn imposed a heavy financial burden on the Knights from which they never recovered. They had to pay an indemnity in silver, estimated at ten times the annual income of the King of England, in four annual installments.[40] To meet the payments, the Knights borrowed heavily, confiscated gold and silver from churches, and increased taxes. Two major Prussian cities, Danzig (Gdańsk) and Thorn (Toruń), revolted against the tax increases. The defeat at Grunwald left the Teutonic Knights with few forces to defend their remaining territories. Since both Poland and Lithuania were now Christian countries, the Knights had difficulties recruiting new volunteer crusaders.[42] The Grand Masters then needed to rely on mercenary troops, which proved an expensive drain on their already depleted budget. The internal conflicts, economic decline and tax increases led to unrest and the foundation of the Prussian Confederation, or Alliance against Lordship, in 1441. That, in turn, led to a series of conflicts that culminated in the Thirteen Years' War (1454).[43]

In popular culture

The war has been popularized in Polish popular culture, primarily due to the impact of the novel The Knights of the Cross (1900) by Polish writer Henryk Sienkiewicz, which have led to numerous adaptions such as a movie (1960) and a video game (2002).

References

- Ekdahl 2008, p. 175

- Stone 2001, p. 16

- Urban 2003, p. 132

- Kiaupa, Kiaupienė & Kunevičius 2000, p. 137

- Turnbull 2003, p. 20

- Ivinskis 1978, p. 336

- Urban 2003, p. 130

- Kuczynski 1960, p. 614

- Jučas 2009, p. 51

- Turnbull 2003, p. 21

- Kiaupa, Kiaupienė & Kunevičius 2000, p. 139

- Christiansen 1997, p. 227

- Turnbull 2003, p. 30

- Jučas 2009, p. 75

- Jučas 2009, p. 74

- Turnbull 2003, p. 33

- Urban 2003, p. 142

- Turnbull 2003, p. 35

- Turnbull 2003, pp. 36–37

- Urban 2003, pp. 148–149

- Jučas 2009, p. 77

- Jučas 2009, pp. 57–58

- Разин 1999, pp. 485–486

- Turnbull 2003, p. 43

- Turnbull 2003, p. 45

- Turnbull 2003, pp. 48–49

- Turnbull 2003, p. 64

- Turnbull 2003, p. 66

- Urban 2003, p. 157

- Turnbull 2003, p. 68

- Jučas 2009, p. 88

- Urban 2003, p. 162

- Paweł Jasienica (1978). Jagiellonian Poland. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 108–109.

- Urban 2003, p. 164

- Stone 2001, p. 17

- Ivinskis 1978, p. 342

- Turnbull 2003, p. 75

- Turnbull 2003, p. 74

- Urban 2003, p. 166

- Christiansen 1997, p. 228

- Kiaupa, Kiaupienė & Kunevičius 2000, pp. 142–144

- Christiansen 1997, pp. 228–230

- Stone 2001, pp. 17–19

Bibliography

- Christiansen, Eric (1997), The Northern Crusades (2nd ed.), Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-026653-4

- Ekdahl, Sven (2008), "The Battle of Tannenberg-Grunwald-Žalgiris (1410) as reflected in Twentieth-Century monuments", in Victor Mallia-Milanes (ed.), The Military Orders: History and Heritage, 3, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7546-6290-7

- Ivinskis, Zenonas (1978), Lietuvos istorija iki Vytauto Didžiojo mirties (in Lithuanian), Rome: Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademija, OCLC 464401774

- Jučas, Mečislovas (2009), The Battle of Grünwald, Vilnius: National Museum Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, ISBN 978-609-95074-5-3

- Kiaupa, Zigmantas; Kiaupienė, Jūratė; Kunevičius, Albinas (2000), The History of Lithuania Before 1795, Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, ISBN 9986-810-13-2

- Kuczynski, Stephen M. (1960), The Great War with the Teutonic Knights in the years 1409–1411, Ministry of National Defence, OCLC 20499549

- Разин, Е. А. (1999), История военного искусства XVI – XVII вв. (in Russian), 3, Издательство Полигон, ISBN 5-89173-041-3

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Tannenberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights, Campaign Series, 122, London: Osprey, ISBN 978-1-84176-561-7

- Stone, Daniel (2001), The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5

- Urban, William (2003), Tannenberg and After: Lithuania, Poland and the Teutonic Order in Search of Immortality (Revised ed.), Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, ISBN 0-929700-25-2