Poison River

Poison River is a graphic novel by American cartoonist Gilbert Hernandez, published in 1994 after serialization from 1989 to 1993 in the comic book Love and Rockets. The story follows the life of the character Luba from her birth until her arrival in Palomar, the fictional Central American village in which most of Hernandez's stories in Love and Rockets take place.

The non-linear, magic realist story is complex and experimental. It traces the first eighteen years of Luba and her growing extended family during the 1950s–70s as they trek through a fictional Latin American country, while social and political events intrude upon their lives. Each chapter focuses on a different character—Luba herself rarely takes center stage. The story ends with Luba and her family appearing at the outskirts of the village of Palomar at the point when Hernandez's first Palomar story begins.

Long-time readers of Love and Rockets found the serialization of Poison River difficult to follow, and new readers found it disorienting and offputting. Unlike in his previous serial, Human Diastrophism, Hernandez made no attempt to mold the instalments into episodes to fit the serial nature of Love and Rockets. When Poison River appeared in book form in 1994, Hernandez expanded the page count and altered and added panels to improve the reading experience. The book was a turning point for Hernandez and his approach to comics and is an early example of the growing pains the graphic novel form suffered in the 1980s and 1990s.

Background and publication

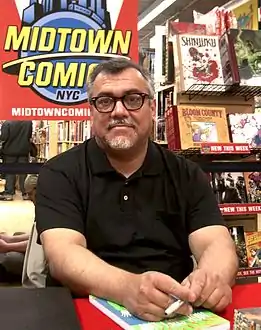

The alternative comic book Love and Rockets began publication in the early 1980s,[lower-alpha 1] showcasing the work of the Hernandez brothers: Mario (b. 1953), Gilbert (b. 1957), and Jaime (b. 1959).[1] The stories featured sensitive portrayals of prominent female and multiethnic characters—especially Latinos—which were uncommon in American comics of the time.[2]

A version of Gilbert Hernandez's Luba appeared in the first issue, but the character as she was to be known first appeared in his Heartbreak Soup stories as a strong-willed, hammer-wielding bañadora bathhouse girl. She eventually makes her way to the center of political and social happenings in the fictional Latin American village of Palomar, but little was related of her pre-Palomar life.[3] Hernandez gradually took advantage of serialization to broaden his narrative scope;[2] the stories became longer and more ambitious, and Hernandez delved more deeply into the backgrounds of his characters[4] and their community,[5] and sociopolitical issues.[6] In issues #21–26 appeared Human Diastrophism[7]—a complex story in which politics and the outside world intrude on the insular Palomar with dramatic consequences.[8]

Hernandez serialized Poison River in Love and Rockets #29–40[9] alongside his Love and Rockets X serial and Jaime's eight-part Wig Wam Bam. Unlike with Human Diastrophism, he made no attempt to mold the serialization into discrete episodes in Love and Rockets.[10] The completed work first appeared in 1994[9] as volume 12 of Love and Rockets. In 2007 it was included in the Beyond Palomar volume of The Love and Rockets Library along with Love and Rockets X.[7] For the completed book edition Hernandez divided the story into seventeen chapters and added another sixteen pages, and prefaced each chapter with an illustration of one of the characters, suggesting the chapter was to focus on that character.[11]

Synopsis

Luba and her growing extended family trek through a fictional Latin American country from the 1950s to the 1970s, with social and political events intruding in their lives.[12] The story focuses mostly on the people around Luba, with a chapter on each—Luba herself rarely takes center stage.[13] The story finishes at the point where the first Heartbreak Soup story begins.[lower-alpha 2][10]

The story opens as Luba's mother Maria is thrown out of her wealthy husband's house when he discovers he is not Luba's father. She soon finds a rich lover and abandons Luba and Luba's poor, native father, who takes Luba to his sister Hilda far across the country. Hilda's daughter Ofelia reluctantly takes to raising Luba. Ofelia and her communist friends are ambushed by rightists, and Ofelia is raped and left for dead; she thereafter suffers from a back injury she tells Luba resulted from a church falling on her.

As a teenager, Luba works as a bañadora bathhouse girl, until the middle-aged conga player Peter Rio discovers her. Peter, his father Fermin, and the gangster Garza had been rival lovers of Maria's, and to get back at Garza Peter marries an unsuspecting Luba. He abandons music to return to life as a gangster, a life he shields Luba from. In her restlessness, Luba takes to clubbing and using intravenous drugs. She becomes pregnant, possibly by the police officer José Ortiz, and goes into labor after shooting up drugs. Luba is told the baby is stillborn, but it has actually been taken and sold on the black market to fulfill a deal Peter had made when he had bought a baby for his intersexual mistress Isobel—who had also been a mistress of his father's.

Peter's estranged father Fermin moves in with Peter and Luba. Isobel and former bandmates of Peter's plot to frame Peter as a secret leftist; the machinations result in paranoia and a large number of gang killings. Peter suffers a debilitating stroke, but manages to kill Fermin when he learns Fermin murdered Isobel. Luba is made to flee and returns to Ofelia and Hilda, who have lost their home. They make their way across the country, and stay with a commune, where Luba gets pregnant again before rightists shut down the commune and they flee again. Luba, her daughter Maricela, and Ofelia find themselves on the outskirts of the village of Palomar, where they begin a new life.

Style and analysis

Poison River is Hernandez's longest and most complex work.[15] The highly experimental and non-linear book lacks traditional narrative transitions and features magic realist storytelling.[9] Hernandez has stated that his intention was to create an "epic", a complex graphic novel of Luba's life, putting "everything [he] possibly had going on in [his] head" into the work.[16] Cold War-era political tensions form a prominent backdrop to the story, in which right-wing gangsters and others brutally target leftists such as Ofelia and her communist-sympathizer friends, who burn US President Eisenhower in effigy.[17]

Few details of Luba's pre-Palomar life surfaced in earlier stories.[18] "Act of Contrition" (1984)[lower-alpha 3] flashes back to her teenage nightclubbing days, and Hernandez recreates a panel from these flashbacks in Poison River.[19] The story traces the first eighteen years of Luba's life, known to long-time Love and Rockets fans as the bañadora ("bath-giver") of the fictional Latin American village of Palomar.[12] Luba rarely takes center stage in the narrative; rather, she provides a focal point around which the stories of the otherwise unrelated large cast of characters come together.[20] The characters lives are intertwined in ways they are never aware of. An example: a terrorist attack forces Ofelia, Luba, and Ofelia's mother Hilda to flee and permanently injures Ofelia's back; the coordinators of the attack are associates of Peter Rio, whom Luba meets and marries in the city Luba and Hilda eventually make their way to.[21]

Over the course of Love and Rockets, the Hernandez brothers made increasing using of what Joseph Witek calls "uncued closure":[lower-alpha 4] frequent use of abrupt ellipsis to pack large amounts of narrative into a small number of panels, relying on readers to fill in the gaps.[22] In Poison River the gaps between panels, which readers normally processed unconsciously, come to the forefront in a slow, staccato rhythm. Panels are crowded with abundant dialogue, stretching out their perceived duration in time, while transitions from one panel to another are sudden—as are transitions from scene to scene, which can happen several times per page. Hernandez limits the narrative only to important details, showing rapid growth in his characters and situations in limited space, rather than relating the story in a traditional step-by-step manner.[23] He compresses great a great deal of action into a minimum of panels, as in a two panel sequence which critic Jordan Raphael says "delineates both the entirety (action and consequences) of a shootout between rival gangs even as [Henrandez] reveals each character's guiding motivation".[20] The narrative's chronology is fluid, with frequent jumps in time, such as an uncued 16-page flashback sequence.[19] Hernandez avoids using captions, leaving such jumps to the reader to sort out. The copious, compact dialogue gives the reader an impression of what is going on at a given moment, but filtered through the speaker.[23]

Poison River's dark tone and chauvinistic male-dominated social background set it apart from Hernandez's earlier stories. While women take prominent roles in the social and political life of Palomar, a patriarchal mood dominates Poison River's crime-ridden cities.[24] The men exclude the women from the men's decision-making, and shield them from larger social issues, such as controversies regarding abortion, which Peter insists should not be discussed in Luba's presence.[25]

Hernandez renders his cartoons in a high-contrast balance of blacks and whites with a line Jordan described as "alternatively loose and tight".[20] His expressionistic style ranges from naturalism to exaggerated cartoon distortion, a highly stylized approach that nonetheless captures nuances of expression and the individuality of his characters' features. The stronger the emotion his characters express, the more exaggerated and cartoony the drawing becomes. His style assimilates an eclectic variety of influences from comic strips and both mainstream and underground comics, drawing most strongly from the dynamic cartooning of Harvey Kurtzman, Steve Ditko, and Robert Crumb.[26]

Reception and legacy

Poison River has earned a reputation as Hernandez's most complex and difficult work.[27] Readers of Love and Rockets found the story's complexity and non-linearity confusing and hard to follow. New readers to Love and Rockets had an especially difficult time orienting themselves to the story.[10] During the serialization Hernandez turned to other outlets to take the pressure off completing Poison River, such as in the pornographic Birdland series in which two-dimensional, carefree characters have promiscuous sex without fear of AIDS or pregnancy. The poor reader reception of Poison River contributed to the Hernandez brothers' decision to bring Love and Rockets to an end in 1996, by which point Gilbert had already returned to more self-contained Palomar stories that were easier for a serial readership to consume.[15]

During Poison River's serialization, Love and Rockets #36 was among a number of publications marked "Adults Only" and wrapped in plastic that were seized by the South African vice squad. It was cited for nudity and explicit sex; the judgment found it indecent under section 47(2)(a) of the South African Publications Act 42 of 1974 and declared "there appears to be no merit whastoever" to it and that it would "transgress the tolerance of the reasonale reader who will regard this as a blatant intrusion upon the privacy of the human body as well as the sex act".[28]

Hernandez found serialization an impediment to the type of storytelling he was attempting with Poison River. Since its completion, he has chosen to serialize certain works, such as Julio's Day (2012) and Me for the Unknown in the second volume of Love and Rockets; and to publish others as stand-alone graphic novels, such as Sloth (2006) and Chance in Hell (2007).[9] In 2013 Hernandez returned to the story of Maria with the Maria M. volumes, in which Henrandez takes a metatextual approach with Luba's half-sister Fritz re-enacting their mother's life in a B movie.[29]

Critic Anne Rubenstein found the jumps in time and physical similarity of many characters—many related to each other—to be particularly hard to keep track of, especially compared to Love and Rockets X, whose chronology was straightforward and whose characters were much easier to tell apart visually. The tight plot, she says, was particularly demanding for readers, as careless reading early on could easily result in a lack of understanding later.[30] Teachers such as Derek Parker Royal have commented that their students are often confused by, or resistant to, the complexity of Poison River.[31] Latin American cultural references largely unfamiliar to English-speaking audiences, such as to lucha libre, Frida Kahlo, Cantinflas, and Memín Pinguín, may also have played in a role in the book's cold reception.[30]

In 1997 Publishers Weekly described the work as "an epic Latin American melodrama of lost identity, political violence and polymorphous sexuality", whose "complex plotting is occasionally confusing", but with "characterizations, dialogue and relationships [that] are vividly, emotionally engaging".[32] Charles Hatfield considered Poison River "the apogee of Hernandez's art to date" for "wed[ding] formal complexity to thematic ambition".[27] Québécois cartoonist and comics critic David Turgeon considered Poison River "a major comics work of uncommon inspiration".[23] Dominican-American writer Junot Díaz stated he likely would not have become a writer if he had not read Poison River.[33]

Notes

- The first self-published issue appeared in 1981; the first Fantagraphics issue from 1982 is an expanded reprint of the self-published issue.

- The first Heartbreak Soup story, "Sopa de Gran Pena", first appeared in Love and Rockets #3–4.[14]

- "Act of Contrition" first appeared in Love and Rockets #5–7.[10]

- "Closure" in this sense is a term Scott McCloud introduced in Understanding Comics (1993) to refer to reader's role in closing narrative gaps between comics panels.[22]

References

- Hatfield 2005, p. 68; Royal 2009, p. 262.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 69.

- Knapp 2001.

- Glaser 2013.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 71.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 68–69.

- Royal 2013.

- Molesworth 2013.

- Royal 2009, p. 262.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 102.

- Royal 2009, p. 265.

- Rubenstein 1994, p. 47.

- Rubenstein 1994, p. 47; Raphael 1997.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 74.

- Pizzino 2013.

- Gaiman 1995, p. 93.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 91–92.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 88–89.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 89.

- Raphael 1997, p. 49.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 91.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 70.

- Turgeon 2009.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 89–90.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 90.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 71–72.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 88.

- Potter 1992, p. 13.

- Aldama 2016, pp. 41, 44.

- Rubenstein 1994, p. 48.

- Royal 2009, p. 277.

- Publishers Weekly staff 1997.

- New York Times staff 2012.

Works cited

- Aldama, Frederick Luis (2016). "Recreative Graphic Novel Acts in Gilbert Hernandez's Twenty-First-Century Neo Noirs". In Aldama, Frederick Luis; González, Christopher (eds.). Graphic Borders: Latino Comic Books Past, Present, and Future. University of Texas Press. pp. 41–63. ISBN 978-1-4773-0915-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaiman, Neil (July 1995). "The Hernandez Brothers". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (178): 91–123.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glaser, Jennifer (2013). "Picturing the Transnational in Palomar: Gilbert Hernandez and the Comics of the Borderlands". ImageTexT. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hatfield, Charles (2005). "Gilbert Hernandez's Heartbreak Soup". Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 68–107. ISBN 978-1-57806-719-0. Retrieved 2012-09-19 – via Project MUSE.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knapp, Tom (2001-08-10). "Love & Rockets #12: Poison River". Rambles. Archived from the original on 2002-02-09. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Molesworth, Jesse (2013). "Comics as Remediation: Gilbert Hernandez's Human Diastrophism". ImageTexT. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- New York Times staff (2012-08-30). "Junot Díaz: By the Book". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-11-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pizzino, Christopher (2013). "Autoclastic Icons: Bloodletting and Burning in Gilbert Hernandez's Palomar". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Potter, Valerie (May 1992). "Comics Banned in South Africa". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (150): 13–15. ISSN 0194-7869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Publishers Weekly staff (1997-09-29). "Love & Rockets #12 Poison River". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- Raphael, Jordan (December 1997). Groth, Gary (ed.). "Poison River". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (200): 49. ISSN 0194-7869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royal, Derek Parker (Spring 2009). "To Be Continued...: Serialization and its Discontent in the Recent Comics of Gilbert Hernandez". International Journal of Comic Art: 262–280.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royal, Derek Parker (2013). "Hernandez Brothers: A Selected Bibliography". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved 2014-11-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rubenstein, Anne (November 1994). "Difficult Pleasures: Poison River". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (172): 47–48. ISSN 0194-7869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turgeon, David (September 2009). "Poison River and the vertiginous ellipsis". du9. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- O'Connor, Patrick (2004). "Conclusion/Epilogue: Perverse Narratives on the Border". Latin American Fiction and the Narratives of the Perverse: Paper Dolls and Spider Women. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 193–210. ISBN 978-1-4039-7870-7.

- Sobel, Marc; Valenti, Kristy (2013). The Love and Rockets Companion: 30 Years (and Counting). Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-1-60699-579-2.