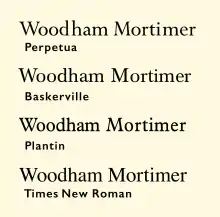

Plantin (typeface)

Plantin is an old-style serif typeface named after the sixteenth-century printer Christophe Plantin.[1] It was created in 1913 by the British Monotype Corporation for their hot metal typesetting system, and is loosely based on a Gros Cicero face cut in the 16th century by Robert Granjon and held in the collection of the Plantin-Moretus Museum of Antwerp.[2]

| |

| Category | Serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Old style serif |

| Designer(s) | Robert Granjon Frank Hinman Pierpont Fritz Stelzer |

| Foundry | Monotype |

| Date created | 1913 |

The intention behind the design of Plantin was to create a font with thicker letterforms than were often used at the time: previous type designers had reduced the weight of their fonts to make up for the effect of ink spread or to achieve a more elegant image, but by 1913 innovations in smoothing and coating paper had led to reduced ink spread.[3] In preparing the design Monotype engineering manager Frank Hinman Pierpont visited the Plantin-Moretus Museum, which provided him with a printed specimen.[4]

Plantin was one of the first Monotype Corporation revivals that was not simply a copy of a typeface already popular in British printing; it has proved popular since its release and has been digitised. It can in retrospect be seen to have paved the way for the many Monotype revivals of classic typefaces that followed in the 1920s and 30s.[1] Plantin would later also be used as one of the main models for the creation of Times New Roman in the 1930s.[5] The Plantin family includes regular, light and bold weights, along with corresponding italics.

Inspiration

At the time Plantin was released, Monotype's hot metal typesetting system, which cast new type for each printing job, was developing a reputation for practicality in trade and mass-market printing, but the designs offered by Monotype were relatively basic choices, such as a "modern" face, an "old style" and a Clarendon.[1] It was suggested by James Moran and John Dreyfus that the existence of a c. 1910 family from the Shanks foundry known as "Plantin Old Style" may have been an inspiration. This was actually a bold design based on Caslon, with no connection to Plantin but it was also a design advertised as being highly legible, so Dreyfus suggests it may have prompted the choice of design and name.[6]

The Plantin-Moretus Museum, created in 1876 from Plantin's collection which had been preserved and added to by his successors, is notable as the world's largest collection of sixteenth century typefaces, leading Pierpont to visit it to research the topic.[7] The Granjon font on which Pierpont's design was based was listed as one of the types used by the Plantin-Moretus Press beginning in the 17th century, long after Plantin had died and his press had been inherited by the Moretus family. (It has been reported that Plantin himself had used a few letters of the font to supplement another font, a Garamond, but H. D. L. Vervliet (2008) suggests that these may have been a set of slightly different custom sorts cut by Granjon.[3][4][8][9])

Plantin was designed and engraved into metal at the Monotype factory in Salfords, Surrey, which was led by Pierpont and draughtsman Fritz Stelzer. Both were recruits to Monotype from the German printing industry. The choice to revive a French renaissance design was unusual for the time, since most British fine printers of the period preferred either Caslon or revivals of the fifteenth-century style of Nicolas Jenson (recognisable from the tilted 'e'), following the lead of William Morris's Golden Type, both of which Monotype would also develop revivals of.[1] However, other revivals of Aldine/French renaissance typefaces followed from several hot metal typesetting companies in the following decades, including Monotype's own Poliphilus, Bembo and Garamond, Linotype's Granjon and Estienne and others, becoming very popular in book printing for body text.

Design

The design for Plantin preserved the large x-height of Granjon's designs, but shortened the ascenders and descenders and enlarged the counters of the lowercase 'a' and 'e'.[4] Not all the letters were Granjon's: the letters 'J', 'U' and 'W', not used in French in the sixteenth century, were not his, and a different 'a' in an eighteenth-century style had been substituted into the font by the time the specimen sheet was printed.[10][11]

The 1742 specimen of Claude Lamesle (notable for its printing quality) provides a specimen of the Granjon type in its original state.[12][9] Mosley has close-up images of some characters of the face.[11][lower-alpha 1]

Reception and usage

With its relatively robust, solid design compared to the Didone and "Modernised Old Style" faces popular in the early twentieth century (which Monotype already had made versions of), Plantin proved popular and was often particularly used by trade and newspaper printers using poor-quality paper in the metal type period and beyond. Monotype's advertising emphasised its popularity with advertisers, highlighting its use in the "Mrs Rawlins" series of adverts for washing starch.[14][15][16][17]}} As the basic font is relatively dark on the page, Monotype offered a 'light' version as well as a bold, which Hugh Williamson describes as "particularly suitable for bookwork."[18]

During the interwar period the face was adopted and popularized by Francis Meynell's Pelican Press and by C. W. Hobson's Cloister press, and also used occasionally by Cambridge University Press.[4] A custom version, "Nonesuch Plantin" was also cut for Meynell's Nonesuch Press, one of the first fine printers to use Monotype machines, with extended ascenders and descenders on the lower-case.[19] Type designer Walter Tracy noted that this changed the type's appearance to a surprising extent: "it look[s] not only more refined but as if it derived from another period: Fournier's, say [in the eighteenth century], not Granjon's."[20] It was appropriately used by the Bodley Head to print Meynell's autobiography.[21] Monotype also created a condensed version, News Plantin, for The Observer in the late 1970s.[22][1] An infant variety of the typeface also exists, with single-story versions of the letters 'a' and 'g' and a 'y' with two straight sides.

The font was used as the signature font for ABC News from 1978 until 1999. In more recent usage, the magazine Monocle is set entirely in Plantin and Helvetica.[23]

Plantin was the basis for the general layout of Monotype's most successful typeface of all, Times New Roman.[24][25] Times is similar to Plantin but "sharpened" or "modernised", with increased contrast (particularly resembling designs from the eighteenth and nineteenth century) and greater "sparkle".[26][27][28] Allan Haley commented that Times New Roman "looks like Plantin on a diet."[29]

Various unofficial digitisations (including simple knock-offs) and more complete adaptations of Plantin have been released. Galaxie Copernicus by Chester Jenkins and Kris Sowersby is an unofficial digitisation.[30] Sowersby followed it up with a newspaper typeface, Tiempos, influenced by Times New Roman.[31][32]

References

- A better-quality digitisation of the whole specimen is available but it does not include this leaf.[13]

- Slinn, Judy; Carter, Sebastian; Southall, Richard. History of the Monotype Corporation. pp. 202–3 etc.

- Schuster, Brigitte (2010). "Monotype Plantin: A Digital Revival by Brigitte Schuster" (PDF). Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (M.A. thesis). Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Carter, Sebastian (1995), Twentieth Century Type Designers, W. W. Norton & Company, pp. 28–29.

- Morison, Stanley (7 June 1973). A Tally of Types. CUP Archive. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-0-521-09786-4.

- Meggs, Philip B.; Carter, Rob (1993), "29. Plantin", Typographic Specimens: The Great Typefaces, John Wiley and Sons, pp. 302–311, ISBN 978-0-471-28429-1.

- Dreyfus, John (1995). Into Print: Selected Writings on Printing History, Typography and Book Production (1st hardcover ed.). Boston: David R. Godine. pp. 116–124. ISBN 9781567920451.

- Mosley, James. "The materials of typefounding". Type Foundry. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Mann, Meredith. "Where Did Times New Roman Come From?". New York Public Library. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Hendrik D. L. Vervliet (2008). The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-century Typefaces. BRILL. pp. 226–7. ISBN 978-90-04-16982-1.

- Mosley, James (2003). "Reviving the Classics: Matthew Carter and the Interpretation of Historical Models". In Mosley, James; Re, Margaret; Drucker, Johanna; Carter, Matthew (eds.). Typographically Speaking: The Art of Matthew Carter. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 9781568984278.

Plantin was a recreation of one of the old types held at the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, of which a specimen, printed in 1905, had been acquired by Pierpont on a visit. The type from which the specimen was printed was not only centuries old and worn almost beyond use, but it was contaminated with wrong-font letters (notably the letter ‘a’) and the italic did not even belong to the roman. The revival, derived by Monotype from an indirect and confused original, is as sound a piece of type-making as was ever created in the 20th century…behind the foggy image of the roman type lies the...'Gros Cicero' Roman of Robert Granjon, acquired by the Plantin printing office after the death of its founder.

- Mosley, James. "Comments on Typophile thread". Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 2011-10-13. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

The consensus appears to be that not only the wrong-fount a in the cases at Antwerp but also the italic that Monotype adapted for their Plantin (which can be seen on that first page of the 1905 specimen) may be the work of Johann Michael Schmidt (died 1750), also known as J. M. Smit or Smid.

- Lamesle, Claude (1742). Épreuves générales des caracteres. p. 55.

- Lamesle, Claude (1742). Épreuves générales des caracteres.

- "Monotype (advert)". Modern Publicity: 187. 1930. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Warde, Beatrice (1932). "Twenty Years of Advertising Typography". Advertiser's Weekly: 130. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Hackney, Fiona Anne Seaton. ""They Opened Up a Whole New World": Feminine Modernity and the Feminine Imagination in Women's Magazines, 1919-1939" (PDF). Goldsmith's College (PhD thesis). Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Lucy Lethbridge (14 March 2013). Servants: A Downstairs View of Twentieth-century Britain. A&C Black. pp. 187–8. ISBN 978-1-4088-3407-7.

- Williamson, Hugh. Methods of Book Design. Oxford University Press. p. 81.

- Steeves, Andrew (14 April 2011). "Poetry Books for the Trala". Gaspereau Press. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Tracy, Walter. Letters of Credit. pp. 50–1.

- Joseph Rosenblum (1995). A Bibliographic History of the Book: An Annotated Guide to the Literature. Scarecrow Press. pp. 407–8. ISBN 978-0-8108-3009-7.

- Luna, Paul (1986). "Small Print". Designer.

The first national to install a Lasercomp, it overcame the lack of suitable text faces by commissioning its own, a slightly condensed version of Plantin.

- Coles, Stephen (February 13, 2009). "In Use: Plantin for Monocle". The FontFeed. FSI FontShop International. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- Rhatigan, Dan. "Time and Times again". Monotype. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Hutt, Allen (1970). "Times Roman: a re-assessment". Journal of Typographic Research. 4 (3): 259–270. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Lawson, Alexander (1990). Anatomy of a Typeface. New York: David R. Godine. pp. 270–294. ISBN 9780879233334. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Morison, Stanley. "Changing the Times". Eye. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Allan Haley (15 September 1992). Typographic Milestones. John Wiley & Sons. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-471-28894-7.

- Haley, Allen (1990). ABC's of type. Watson-Guptill Publications. p. 86. ISBN 9780823000531.

- Heck, Bethany. "Galaxie Copernicus review". Font Review Journal. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Sowersby, Kris. "Tiempos Design Information". Klim Type Foundry. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- Thomson, Mark; Sowersby, Kris. "Reputations: Kris Sowersby". Eye. Retrieved 12 September 2019.