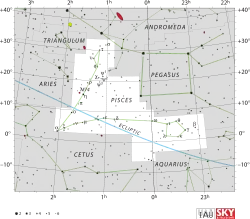

Pisces (constellation)

Pisces is a constellation of the zodiac. Its vast bulk – and main asterism viewed in most European cultures per Greco-Roman antiquity as a distant pair of fishes connected by one cord each that join at an apex – are in the Northern celestial hemisphere. Its name is the Latin plural for fish. It is between Aquarius, of similar size, to the southwest and Aries, which is smaller, to the east. The ecliptic and the celestial equator intersect within this constellation and in Virgo. This means the sun passes directly overhead of the equator, on average, at approximately this point in the sky, at the March equinox.

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Psc |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Piscium |

| Pronunciation | /ˈpaɪsiːz/, genitives /ˈpɪʃiəm/ |

| Symbolism | the Fishes |

| Right ascension | 1h |

| Declination | +15° |

| Quadrant | NQ1 |

| Area | 889 sq. deg. (14th) |

| Main stars | 18 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 86 |

| Stars with planets | 13 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 8 |

| Brightest star | η Psc (Alpherg) (3.62m) |

| Messier objects | 1 |

| Meteor showers | Piscids |

| Bordering constellations | |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −65°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of November. | |

Its symbol is ![]() (Unicode ♓).

(Unicode ♓).

Features

The March equinox is currently located in Pisces, due south of ω Psc, and, due to precession, slowly drifting due west, just below the western fish towards Aquarius.

Stars

- Alrescha ("the cord"), otherwise Alpha Piscium (α Psc), 309.8 lightyears, class A2, magnitude 3.62

- Fumalsamakah[1] ("mouth of the fish"), otherwise Beta Piscium (β Psc), 492 lightyears, class B6Ve, magnitude 4.48

- Delta Piscium(δ Psc), 305 lightyears, class K5III, magnitude 4.44

- Epsilon Piscium (ε Psc), 190 lightyears, class K0III, magnitude 4.27

- Revati[1] ("rich"), otherwise Zeta Piscium (ζ Psc), 148 lightyears, class A7IV, magnitude 5.21

- Alpherg ("emptying"),[1] otherwise Eta Piscium (η Psc), 349 lightyears, class G7 IIIa, magnitude 3.62

- Torcular ("thread"),[1] otherwise Omicron Piscium (ο Psc), 258 lightyears, class K0III, magnitude 4.2

- Omega Piscium (ω Psc), 106 lightyears, class F4IV, magnitude 4.03

- Gamma Piscium (γ Psc), 320 lightyears, magnitude 12.078

- Van Maanen's Star is the closest-known white dwarf to us, 12.35 magnitude

Deep-sky objects

M74 is a loosely wound (type Sc) spiral galaxy in Pisces, found at a distance of 30 million light years (redshift 0.0022). It has many clusters of young stars and the associated nebulae, showing extensive regions of star formation. It was discovered by Pierre Méchain, a French astronomer, in 1780. A type II-P supernova was discovered in the outer regions of M74 by Robert Evans in June 2003; the star that underwent the supernova was later identified as a red supergiant with a mass of 8 solar masses.[2]

NGC 488 is an isolated face-on prototypical spiral galaxy.

NGC 520 is a pair of colliding galaxies located 90 million lightyears away.

CL 0024+1654 is a massive galaxy cluster that lenses the galaxy behind it, creating arc-shaped images of the background galaxy. The cluster is primarily made up of yellow elliptical and spiral galaxies, at a distance of 3.6 billion light-years from Earth (redshift 0.4), half as far away as the background galaxy, which is at a distance of 5.7 billion light-years (redshift 1.67).[2]

History and mythology

Pisces originates from some composition of the Babylonian constellations Šinunutu4 "the great swallow" in current western Pisces, and Anunitum the "Lady of the Heaven", at the place of the northern fish. In the first-millennium BC texts known as the Astronomical Diaries, part of the constellation was also called DU.NU.NU (Rikis-nu.mi, "the fish cord or ribbon").[3]

Greco-Roman period

Pisces is associated with the Greek legend that Aphrodite and her son Eros either shape-shifted into forms of fishes to escape, or were rescued by two fishes.

In the Greek version according to Hyginus, Aphrodite and Eros while visiting Syria fled from the monster Typhon by leaping into the Euphrates River and transforming into fishes (Poeticon astronomicon 2.30, citing Diognetus Erythraeus).[4] The Roman variant of the story has Venus and Cupid (counterparts for Aphrodite and Eros) carried away from this danger on the backs of two fishes (Ovid Fasti 2.457ff).[5][6]

There is also a somewhat different origin tale that Hyginus preserved in another work. According to this, an egg rolled into the Euphrates, and some fishes nudged this to shore, after which the doves sat on the egg until Aphrodite (thereafter called the Syrian Goddess) hatched out of it. The fishes were then rewarded by being placed in the skies as a constellation (Fabulae 197).[7][8] This story is also recorded by the Third Vatican Mythographer.[9]

Modern period

In 1690, the astronomer Johannes Hevelius in his Firmamentum Sobiescianum regarded the constellation Pisces as being composed of four subdivisions:[10]

- Piscis Boreus (the North Fish): σ – 68 – 65 – 67 – ψ1 – ψ2 – ψ3 – χ – φ – υ – 91 – τ – 82 – 78 Psc.

- Linum Boreum (the North Cord):[10] χ – ρ,94 – VX(97) – η – π – ο – α Psc.

- Linum Austrinum (the South Cord):[10] α – ξ – ν – μ – ζ – ε – δ – 41 – 35 – ω Psc.

- Piscis Austrinus (the South Fish):[10] ω – ι – θ – 7 – β – 5 – κ,9 – λ – TX(19) Psc.

Be aware that Piscis Austrinus more often refers to a separate constellation in its own right. Both (smaller) fish depicted in Pisces are said to be the offspring of the one greater fish in the constellation Piscis Austrinus.

In 1754, the astronomer John Hill proposed to sever a southern zone of Pisces as Testudo (the Turtle).[11] 24 – 27 – YY(30) – 33 – 29 Psc.,[12] It would host a natural but quite faint asterism in which the star 20 Psc is the head of the turtle. While Admiral Smyth mentioned the proposal,[13] it was largely neglected by other astronomers, and it is now obsolete.[12]

Western folklore

The Fishes are in the German lore of Antenteh, who owned just a tub and a crude cabin when he met two magical fish. They offered him a wish, which he refused. However, his wife begged him to return to the fish and ask for a beautiful furnished home. This wish was granted, but her desires were not satisfied. She then asked to be a queen and have a palace, but when she asked to become a goddess, the fish became angry and took the palace and home, leaving the couple with the tub and cabin once again. The tub is sometimes recognized as the Great Square of Pegasus.[14]

In non-Western astronomy

The stars of Pisces were incorporated into several constellations in Chinese astronomy. Wai-ping ("Outer Enclosure") was a fence that kept a pig farmer from falling into the marshes and kept the pigs where they belonged. It was represented by Alpha, Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Mu, Nu, and Xi Piscium. The marshes were represented by the four stars designated Phi Ceti. The northern fish of Pisces was a part of the House of the Sandal, Koui-siou.[15]

Astrology

Pisces is a dim zodiac constellation between Aquarius and Aries. While astrological sign, water sign Pisces is deemed to fix on ecliptical longitudes 330° to 0, when the sun figures at these it is now mostly in Aquarius, due to the precession from when the constellation and the sign coincided. Precession results in Western astrology's zodiacal divisions, thus, not corresponding in the current era to the constellations that carry alike names[16] while Jyotiṣa, widely used in Hindu and Jain culture, will assign events to the Sun's current background constellations.[17]

See also

References

- "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe (1st ed.). Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions by J. H. Rogers 1998, page 19 page 19 (table 3, rows 2-3) and page 27

- Hard (2015), pp. 84–85.

- Hard (2015), pp. 85–86.

- Publius Ovidius Naso (1995). Ovid's Fasti: Roman Holidays. Translated by Betty Rose Nagle. Indiana University Press. pp. 69–70, 182. ISBN 9-780-25320-933-7.

- Rigoglioso, Marguerite (2009). The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece. Springer. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-230-62091-9.

- Ridpath (1988), p. 108.

- Van Berg, Paul-Louis (1972). Corpus Cultus Deae Syriae - Ccds: Les Sources Litteraires - Repertoire Des Sources Grecques Et Latines - Sauf Le De Dea Syria - (in French). Brill Archive. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9-789-00403-503-4.

- Hevelius, J., (1690) Firmamentum Sobiescianum, Leipzig, Fig.NN

- Allen, R. H. (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc. p. 163 342. ISBN 978-0-486-21079-7.

- Ciofi, Claudio; Torre, Pietro, Costellazioni Estinte (nate dal 1700 al 1800): Sezione di Ricerca per la Cultura Astronomica

- Smyth, W. H., (1884) The Bedford Catalogue, p. 23

- Staal (1988), pp. 45–46.

- Staal (1988), pp. 45–47.

- Bobrick (2005), pp. 10, 23.

- Johnsen (2004)

Sources

- Ridpath, Ridpath (1988). Star Tales. James Clarke & Co. ISBN 978-0-718-82695-6.

- Ridpath, Ridpath; Tirion, Wil (2007). Stars and Planets Guide (4th ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

- Eratosthenes; Hyginus; Aratus (2015). Hard, Robin (ed.). Constellation Myths: with Aratus's Phaenomena. OUP Oxford. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-0-191-02652-2.

- Richard Hinckley Allen, Star Names, Their Lore and Legend, New York, Dover: various dates.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988). The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars. The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-04-5.

- Thomas Wm. Hamilton, Useful Star Names, Strategic Books, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |