Piano Phase

Piano Phase is a minimalist composition by American composer Steve Reich, written in 1967 for two pianos (or piano and tape). It is one of his first attempts at applying his "phasing" technique, which he had previously used in the tape pieces It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966), to live performance.

Reich further developed this technique in pieces like Violin Phase (also 1967), Phase Patterns (1970), and Drumming (1971).

History

Piano Phase represents Steve Reich's first attempt to apply his "phasing" technique. Reich had earlier used tape loops in It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966), but wanted to apply the technique to live performance.[1] Reich carried out a hybrid test with Reed Phase (1966), combining an instrument (a soprano saxophone) and a magnetic tape.

Not having two pianos at his disposal, Reich experimented by first recording a piano part on tape, and then trying to play mostly in sync with the recording, albeit with slight shifts, or phases, with occasional re-alignments of the twelve successive notes against each other. Reich found the experience satisfying,[2] showing that a musician can phase with concentration.

With the premiere of Reed Phase at Fairleigh Dickinson University in early 1967, Reich and a musician friend, Arthur Murphy, had the opportunity to attempt Piano Phase with two pianos in live concert. Reich discovered that it was possible to dispense with tape and phase without mechanical assistance. Reich experimented phasing with several versions, including a version for four electric pianos titled Four Pianos dating from March 1967, before settling on a final version of the piece written for two pianos.[2] The first performance of the version for four pianos was given on March 17, 1967 at the Park Place Gallery, with Art Murphy, James Tenney, Philip Corner, and Reich himself.[3]

Composition

Reich's phasing works generally have two identical lines of music, which begin by playing synchronously, but slowly become out of phase with one another when one of them slightly speeds up. In Piano Phase, Reich subdivides the work (in 32 measures) into three sections, with each section taking the same basic pattern, played rapidly by both pianists. The music is made up, therefore, of the results of applying the phasing process to the initial twelve-note melody—as such, it is a piece of process music. The composition typically lasts around 15 minutes.

First section

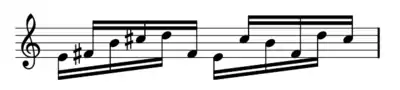

The section begins by both pianists playing a rapid twelve-note melodic figure over and over again in unison (E4 F♯4 B4 C♯5 D5 F♯4 E4 C♯5 B4 F♯4 D5 C♯5). The pattern consists only of 5 distinct pitch classes.

After a while, one pianist begins to play slightly faster than the other. When this pianist is playing the second note of the figure at the same time the other pianist is playing the first note, the two pianists play at the same tempo again. The process is repeated until the process has gone full circle, and the two pianists are playing in perfect unison.

Second section

The second pianist then fades out, leaving the first playing the original twelve-note melody. The first pianist adjusts the bottom part to a four-note motif, which changes the pattern to an 8-note repeating pattern. The second pianist re-enters, but with a distinct 8-note pattern. The phasing process begins again; after the full eight cycles, the first pianist fades out, leaving one eight-note melody playing. The section ends at measure 26.

Third section

The last section introduces the simplest pattern, now in 4/8 meter, built from final four notes of the melody from the previous section,[4] and having only four distinct pitch classes. The other pianist re-enters, the phasing process restarts, and ends when both pianists return to unison. The phase cycle is repeated ad libitum from eight to sixty times according to the score.

Analysis

Piano Phase is an example of "music as a gradual process," as Reich stated in his essay from 1968.[5] In it, Reich described his interest in using processes to generate music, particularly noting how the process is perceived by the listener. (Processes are deterministic: a description of the process can describe an entire whole composition.[5] In other words, once the basic pattern and the phase process have been defined, the music consists itself.)

Reich called the unexpected ways change occurred via the process "by-products", formed by the superimposition of patterns. The superimpositions form sub-melodies, often spontaneously due to echo, resonance, dynamics, and tempo, and the general perception of the listener.[6]

According to musicologist Keith Potter, Piano Phase led to several breakthroughs that would mark Reich's future compositions. The first is the discovery of using simple but flexible harmonic material, which produces remarkable musical results when phasing occurs.[4] The use of 12-note or 12-division patterns in Piano Phase proved to be successful, and Reich would re-use it in Clapping Music and Music for 18 Musicians. Another novelty is the appearance of rhythmic ambiguity during phasing of a basic pattern. The rhythmic perception during phasing can vary considerably, from being very simple (in-phase), to complex and intricate.[6]

The first section of Piano Phase has been the section studied most by musicologists. A property of the first section of phase cycle is that it is symmetric, which results in identical patterns half-way through the phase cycle.[6]

Performance

The piece is played by two pianists without breaks at any stage. A typical performance may last around fifteen to twenty minutes. Reich later adapted the piece for two marimbas, typically played an octave lower than the original.

In 2004, a college student named Rob Kovacs gave the first solo performance of the piece at the Baldwin Wallace Conservatory of Music. Kovacs played both piano parts at the same time on two different pianos. Reich was in the audience for this world premiere performance.[7][8] Others, including Peter Aidu, Leszek Możdżer,[9] and Rachel Flowers[10] have also given solo performances of this piece. In 2016, a concert given by Mahan Esfahani was disrupted by the audience, which started clapping and shouting during the first minutes of the performance.[11]

References

- "Maximum Reich: Introductions". WQXR.

- Potter (2000), p.182

- Potter (2000), p.195

- Potter (2000), p.181-188.

- Steve Reich, "Music as a Gradual Process", in Writings on Music 1965–2000, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 34–36.

- Paul Epstein, Pattern Structure and Process in Steve Reich's Piano Phase, Oxford University Press, The Musical Quarterly 1986 LXXII(4):494-502.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnQdP03iYIo Video recording of the performance

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110719154841/http://moe.bw.edu/~sgreen/expon/archives/20040331/CL33104.pdf An article from Baldwin-Wallace's newspaper, The Exponent, documenting the performance (page 7)

- .Handzlik T. (2011). Finał Sacrum Profanum: Muzyczne i laserowe fajerwerki. Gazeta Wyborcza. <accessed 2011-12-02> - review of the final concert of the Sacrum Profanum Festival, Cracow, 11-17/09/2011, including Steve Reich in audience and on stage. In Polish.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jG0eKE1LVgE

- "Cologne ′stunned′ by audience catcalls at Iranian harpsichordist′s concert - News - DW.COM - 01.03.2016". DW.COM.

External links

- Solo performance by Peter Aidu, October 2006