Petroleum industry in Equatorial Guinea

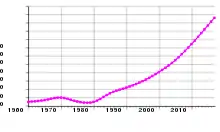

Equatorial Guinea is a significant oil producer in Africa. Crude oil produced by the country is primarily extracted from the Alba, Zafiro, and Ceiba regions. As a result of the recent increase in the extraction of petroleum, the country's economy has grown significantly. In fact, during the period from 1997 to 2001, the country experienced an average GDP growth of 41.6% per year.[1] However, there have been recent accusations of corruption and repression by the government resulting from the nation's newfound wealth.[2]

History

Throughout much of the 1990s, Equatorial Guinea was considered to be a poor country with little prospects of economic growth.[1] Although the country had been rather successful at independence due to its cocoa industry, the Macias regime that quickly exerted its repressive forces eventually diminished it to a shell of its former glory. In fact, the cocoa industry accounted for 75% of the nation's GDP in 1968-- the year of their independence from Spain.[1] However, just 10 years later, the overall cocoa production reduced to one seventh of what it was before.

In 1980, the Spanish petroleum corporation Hispanoil signed in agreement with the Equatoguinean government to form the joint venture GEPSA. Shortly after, the firm successfully drilled a gas well in the Alba region that appeared to be promising. However, the Spanish oil company decided to withdraw from the country in 1990 due to the lack of a viable market for the gas discovered there. As a result, the government allowed for bids from other companies to extract oil.[1]

Walter International was allowed to given the rights to drill in the region. Just one year later, a site close to the original drilling site set up by GEPSA began producing oil. Yet, it was not until 1995, when Mobil struck oil in its Zafiro field, that the country truly became a major oil-producing nation. Soon after in 1999, the American oil firm Triton discovered oil at its Ceiba field.[1]

Due to several corporate changes through the early 2000s, the major oil companies that operated in the country were now owned by American firms. In contrast, there is a notable absence of British oil firms in the country. While Americans dominate the industry, Shell and BP both had yet to explore for oil. As a result of the prevalent presence of foreign firm in the country, foreign direct investment from all over has flooded the nation.[3]

Production and exploration

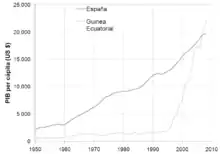

From the dramatic increase in oil production in recent years, Equatorial Guinea has managed to claim the spot as the third largest oil producer in Africa.[3] As a result, its GDP per capita is among the highest in the world. In fact, in 2005, the country had an estimated GDP per capita of $50,240-- only second to that of Luxembourg.[3] In terms of oil extraction, accounting for the three main oil fields that the nation counts on, over 425,000 barrels were extracted per day that same year.[1]

The true turning point in the nation's oil industry came with Mobil's discovery of oil in the Zafiro region. In just a few years, the overall Equatoguinean production of oil increased more than five times over.[1] To the benefit of Mobil and foreign investors in general, the Nigerian and Equatoguinean governments were able to settle a land dispute in the Zafiro region. This paved the way for more confidence among foreign firms hoping to set up shop in the country. However, another important development was the development of the Ceiba oil field by Triton. This proved to be an important development due to its location; it is located far south from the other two oil-producing regions-- away from the Niger Delta. Despite its significant location, it started off as a relatively small operation-- producing just 40,000 barrels per day.[1]

Operating agreements

As is the case in many other developing countries, the Equatoguinean government maintains a stake in much of the oil operations in the country. However, they in no way represent a key player in the industry. For example, they only retain a 3% share in operations in the Alba field and a 5% share in Zafiro field operations.[1] They are merely just another way for the government to extract more revenue from economic activities that take place within its borders.

The American-based Riggs Bank was involved in a corruption scandal in which the US government accused them and Obiang of embezzling millions of dollars from the government treasury into personal bank accounts.[2][3] These allegations highlight the increased level of corruption by high level officials as a result of the amount of wealth that has been brought to Equatorial Guinea's shores.

Political implications

Economic and demographic changes

The rapid rise of the petroleum industry in Equatorial Guinea has provided money for the government from two fronts: oil profits and foreign aid. It is important to note that both of these are without any strings attached.[1] Unlike other developing countries that often have to meet certain requirements to receive aid from foreign donors, the control the government retains overs its oil industry gives them a bargaining chip against any sort of involvement in domestic policies. In fact, there has not been a World Bank lending program for the country since 1999.[1] Additionally, its vast oil reserves allow the government to obtain loans backed by future oil revenues. From these financial resources combined, greater investments in patronage and security forces can implemented.

Given that pools of resources have been secured, Obiang has made it a priority to increase international legitimacy. Juridical statehood to control the money that entered the country and the benefits that come from them. Specifically, he has personally asked the British government for help in running its government in a more efficient manner and providing for more transparency. In return, the government has received praise from many foreign leaders, as the IMF did in 2003.[1] Despite these initiatives, little has actually been done to reduce corruption and improve the lives of the general population.

A number of demographic changes have come since the oil boom. From the increased wealth of the country, populations are more inclined to live in urban settings. However, the higher level of spending has in turn led the domestic currency to inflate. This coupled with a reduction in foreign aid has led to an overall reduction in the standard of living.[1] Although those that are directly employed by oil firms are well-paid by local standards, they represent a small sliver of the population. Additionally, that money stays with the oil companies, as company town models are quite prevalent.[4] Therefore, much of the luxuries that are within the country are only accessible by a select few. This creates a divide between those that are involved with the oil industry and those that are not. In fact, it is a common policy that only those directly employed by the companies are allowed to live within the walls of these compounds; even servants must come and go daily. Thus, this system calls into question whether or not oil money trickles down within the country's society.[5]

Corruption and scandals

Certainly, Obiang's clique has benefited from the control of the country's new wealth.[3] However, there has in recent years been conflicts within the elite as a result of this. In his Esangui clan, there is dispute over who has the greatest influence over domestic policy-- which has traditionally been controlled by his brothers and sons. The public works projects that have been initiated have been inefficient and mostly to facilitate corruption, for which many seek to control the funneling of such funds. Additionally, a lot of wealth is also created through oil contracting companies, from which oil firms derive their labor. However, the nation's biggest ones are controlled by those that are direct family members of Obiang.[2] This highlights the amount of nepotism that is coupled with corruption that cripples the country. From both these sources of wealth, elites have been able to amass a number of luxuries overseas, such as in Washington, D.C., where Obiang and his son are known to frequent and own several opulent properties.[3]

While in many ways Equatorial Guinea can be considered a rentier state, it is not as effective as many states in the Middle East, such as the United Arab Emirates.[3] While it does implement many tactics of repression, it has very little to offer its citizens, and thus the stability of the regime is questionable.[6] Because of this, the number of repressive tactics and human rights abuses have increased since the oil boom.[2] A particular example of this is Black's Prison in Malabo, which has received worldwide attention for the alleged violence and torture that occurs there. This has been particularly useful to coerce or suppress opposition forces that threaten the current regime.[3]

In order to appease critics of corruption within the country, the government in 2004 pledged to sign onto the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. However this does little to combat corruption in that it only makes government salaries more transparent, not expenditures. Additionally, the country has delayed putting into place all the protocols the initiative calls for.[2] Thus, commitments to tackle the corruption and nepotism that are prevalent in the country have been shallow and only for appearances;[2] they have become a handicap towards the development of democracy in Equatorial Guinea.

References

- Frynas, J. G. (2004-10-01). "The oil boom in Equatorial Guinea". African Affairs. 103 (413): 527–546. doi:10.1093/afraf/adh085. ISSN 0001-9909.

- Vines, Alex. (2009). Well oiled : oil and human rights in Equatorial Guinea. Human Rights Watch (Organization). New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-516-7. OCLC 427539691.

- McSherry, Brendan (2006). "The Political Economy of Oil in Equatorial Guinea". African Studies Quarterly. 8 (3): 25–45. ISSN 1093-2658 – via Humanities International Complete.

- Appel, Hannah C (2012). "Walls and white elephants: Oil extraction, responsibility, and infrastructural violence in Equatorial Guinea" (PDF). Ethnography. 13 (4): 439–465. doi:10.1177/1466138111435741. ISSN 1466-1381. JSTOR 43497508. S2CID 145238746.

- Donner, Nicolas (2009). "The Myth of the Oil Curse: Exploitation and Diversion in Equatorial Guinea". Afro-Hispanic Review. 28 (2): 21–42. ISSN 0278-8969 – via JSTOR Journals.

- Appel, Hannah (2012). "Offshore Work: Oil, Modularity, and the How of Capitalism in Equatorial Guinea". American Ethnologist. 39 (4): 692–709. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01389.x. ISSN 0094-0496 – via JSTOR Journals.