Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1

Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1, PGLYRP1, also known as TAG7, is an antibacterial and pro-inflammatory innate immunity protein that in humans is encoded by the PGLYRP1 gene.[5][6][7][8]

Discovery

PGLYRP1 was discovered independently by two laboratories in 1998.[5][7] Håkan Steiner and coworkers, using a differential display screen, identified and cloned Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein (PGRP) in a moth (Trichoplusia ni) and based on this sequence discovered and cloned mouse and human PGRP orthologs.[5] Sergei Kiselev and coworkers discovered and cloned a protein from a mouse adenocarcinoma with the same sequence as mouse PGRP, which they named Tag7.[7] Human PGRP was a founding member of a family of four PGRP genes found in humans that were named PGRP-S, PGRP-L, PGRP-Iα, and PGRP-Iβ (for short, long, and intermediate size transcripts, by analogy to insect PGRPs).[9] Their gene symbols were subsequently changed to PGLYRP1 (peptidoglycan recognition protein 1), PGLYRP2 (peptidoglycan recognition protein 2), PGLYRP3 (peptidoglycan recognition protein 3), and PGLYRP4 (peptidoglycan recognition protein 4), respectively, by the Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee, and this nomenclature is currently also used for other mammalian PGRPs. In 2005, Roy Mariuzza and coworkers crystallized human PGLYRP1 and solved its structure.[10]

Tissue distribution and secretion

PGLYRP1 has the highest level of expression of all mammalian PGRPs. PGLYRP1 is highly constitutively expressed in the bone marrow[5][9][11] and in the tertiary granules of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils and eosinophils),[11][12][13][14][15][16] and to a lesser extent in activated macrophages[15][16] and fetal liver.[9] PGLYRP1 is also expressed in lactating mammary gland,[17] and to a much lower level in corneal epithelium in the eye,[18] in the inflamed skin,[19][20] spleen,[5] thymus,[5] and in epithelial cells in the respiratory[15][16] and intestinal tracts.[5][21] PGLYRP1 is prominently expressed in intestinal Peyer's patches in microfold (M) cells[22][23] and is also one of the markers for differentiation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells into T regulatory (Treg) cells in mice.[24] Mouse PGLYRP1 is expressed in the developing brain and this expression is influenced by the intestinal microbiome.[25] Expression of PGLYRP1 in rat brain is induced by sleep deprivation[26] and in mouse brain by ischemia.[27]

Human PGLYRP1 is also found in the serum after release from leukocyte granules by exocytosis.[28][29] PGLYRP1 is present in camel’s milk at 120 µg/ml[17] and in polymorphonuclear leukocytes’ granules at 2.9 mg/109 cells.[11]

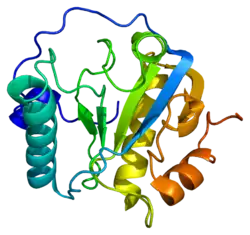

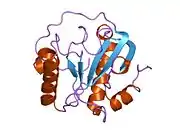

Structure

As with most PGRPs, PGLYRP1 has one carboxy-terminal peptidoglycan-binding type 2 amidase domain (also known as a PGRP domain), which, however, does not have amidase enzymatic activity.[30] This PGRP domain consists of three alpha helices, five beta strands and coils, and an N-terminal segment (residues 1–30, the PGRP-specific segment), whose structure varies substantially among PGRPs.[10] PGLYRP1 has three pairs of conserved cysteines, which form three disulfide bonds at positions 9 and 133, 25 and 70, and 46 and 52 in human PGLYRP1.[10] The Cys46–Cys52 disulfide is broadly conserved in invertebrate and vertebrate PRGPs, Cys9–Cys133 disulfide is conserved in all mammalian PGRPs, and Cys25–Cys70 disulfide is unique to mammalian PGLYRP1, PGLYRP3, and PGLYRP4, but not found in amidase-active PGLYRP2.[9][10] Human PGLYRP1 has a 25 Å-long peptidoglycan-binding cleft whose walls are formed by two α-helices and the floor by a β-sheet.[10]

Human PGLYRP1 is secreted and forms disulfide-linked homodimers.[29][31] The structure of the disulfide-linked dimer is unknown, as the crystal structure of only monomeric human PGLYRP1 was solved, because the crystallized protein lacked the 8 N-terminal amino acids, including Cys8,[10] which is likely involved in the formation of the disulfide-linked dimer. Rat PGLYRP1 is also likely to form disulfide-linked dimers as it contains Cys in the same position as Cys8 in human PGLYRP1,[26] whereas mouse[5] and bovine[11] PGLYRP1 do not contain this Cys and likely do not form disulfide-linked dimers.

Camel PGLYRP1 can form two non-disulfide-linked dimers: the first with peptidoglycan-binding sites of two participating molecules fully exposed at the opposite ends of the dimer, and the second with peptidoglycan-binding sites buried at the interface and the opposite sides exposed at the ends of the dimer.[32] This arrangement is unique for camel PGLYRP1.[32]

PGLYRP1 is glycosylated and glycosylation is required for its bactericidal activity.[31][33]

Functions

The PGLYRP1 protein plays an important role in the innate immune response.

Peptidoglycan binding

PGLYRP1 binds peptidoglycan, a polymer of β(1-4)-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) cross-linked by short peptides, the main component of bacterial cell wall.[5][9][12][14][34][35] Human PGLYRP1 binds GlcNAc-MurNAc-tripeptide with high affinity (Kd = 5.5 x 10−8 M)[14] and MurNAc-tripeptide, MurNAc-tetrapeptide, and MurNAc-pentapeptide with Kd = 0.9-3.3 x 10−7 M[35] with a preference for meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-DAP) over L-lysine-containing peptidoglycan fragments.[35] m-DAP is present in the third position of peptidoglycan peptide in Gram-negative bacteria and Gram-positive bacilli, whereas L-lysine is in this position in peptidoglycan peptide in Gram-positive cocci. Smaller peptidoglycan fragments do not bind or bind with much lower affinity.[14][35]

Camel PGLYRP1 binds MurNAc-dipeptide with low affinity (Kd = 10−7 M)[36] and it also binds bacterial lipopolysaccharide with Kd = 1.6 x 10−9 M and lipoteichoic acid with Kd = 2.4 x 10−8 M at binding sites outside the canonical peptidoglycan-binding cleft with the ligands and PGLYRP1 forming tetramers.[37] Such tetramers are unique to camel PGLYRP1 and are not found in human PGLYRP1 because of stearic hindrance.[37]

Bactericidal activity

Human PGLYRP1 is directly bactericidal for both Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Salmonella enterica, Shigella sonnei, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) bacteria[12][14][31][33][38] and is also active against Chlamydia trachomatis.[39] Mouse[12][13] and bovine[11][28] PGLYRP1 have antibacterial activity against Bacillus megaterium, Staphylococcus hemolyticus, S. aureus, E. coli, and S. enterica, and bovine PGLYRP1 also has antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans.[11]

In Gram-positive bacteria, human PGLYRP1 binds to the separation sites of the newly formed daughter cells, created by bacterial peptidoglycan-lytic endopeptidases, LytE and LytF in B. subtilis, which separate the daughter cells after cell division.[38] These cell-separating endopeptidases likely expose PGLYRP1-binding muramyl peptides, as shown by co-localization of PGLYRP1 and LytE and LytF at the cell-separation sites, and no binding of PGLYRP1 to other regions of the cell wall with highly cross-linked peptidoglycan.[38] This localization is necessary for the bacterial killing, because mutants that lack LytE and LytF endopeptidases and do not separate after cell division, do not bind PGLYRP1, and are also not readily killed by PGLYRP1.[38] In Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli), PGLYRP1 binds to the outer membrane.[38] In both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria PGLYRP1 stays bound to the cell envelope and does not enter the cytoplasm.[38]

The mechanism of killing by PGLYRP1 is based on induction of lethal envelope stress and production of reactive oxygen species in bacteria and the subsequent shutdown of transcription and translation.[38] PGLYRP1-induced bacterial killing does not involve cell membrane permeabilization, which is typical for defensins and other antimicrobial peptides, cell wall hydrolysis, or osmotic shock.[31][33][38]

Human PGLYRP1 has synergistic bactericidal activity with lysozyme[14] and antibacterial peptides.[33] Streptococci produce a protein (SP1) that inhibits antibacterial activity of human PGLYRP1.[40]

Defense against infections

PGLYRP1 plays a limited role in host defense against infections. PGLYRP1-deficient mice are more sensitive to systemic infections with non-pathogenic bacteria (Micrococcus luteus and B. subtilis)[13] and to P. aeruginosa-induced keratitis,[18] but not to systemic infections with pathogenic bacteria (S. aureus and E. coli).[13] Intravenous administration of PGLYRP1 protects mice from systemic Listeria monocytogenes infection.[41]

Maintaining microbiome

Mouse PGLYRP1 plays a role in maintaining healthy microbiome, as PGLYRP1-deficient mice have significant changes in the composition of their intestinal and lung microbiomes, which affect their sensitivity to colitis and lung inflammation.[21][42][43]

Effects on inflammation

Mouse PGLYRP1 plays a role in maintaining anti- and pro-inflammatory homeostasis in the intestine, skin, lungs, joints, eyes, and brain. PGLYRP1-deficient mice are more sensitive than wild type mice to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis, which indicates that PGLYRP1 protects mice from DSS-induced colitis.[21][42] However, in a mouse model of arthritis PGLYRP1-deficient mice develop more severe arthritis than wild type mice.[44] Also, mice deficient in both PGLYRP1 and PGLYRP2 develop more severe arthritis than PGLYRP2-deficient mice, which are resistant to arthritis.[44] These results indicate that PGLYRP2 promotes arthritis and that PGLYRP1 counteracts the pro-inflammatory effect of PGLYRP2.[44] PGLYRP1-deficient mice also have impaired corneal wound healing compared with wild type mice, which indicates that PGLYRP1 promotes corneal wound healing.[18]

PGLYRP1-deficient mice are more resistant than wild type mice to experimentally induced allergic asthma,[15][16] atopic dermatitis,[20] contact dermatitis,[20] and psoriasis-like skin inflammation.[19] These results indicate that mouse PGLYRP1 promotes lung and skin inflammation. These pro-inflammatory effects are due to increased numbers and activity of T helper 17 (Th17) cells and decreased numbers of T regulatory (Treg) cells[15][19][20] and in the case of asthma also increased numbers of T helper 2 (Th2) cells and decreased numbers of plasmacytoid dendritic cells.[15] The pro-inflammatory effect of PGLYRP1 on asthma depends on the PGLYRP1-regulated intestinal microbiome, because this increased resistance to experimentally induced allergic asthma could be transferred to wild type germ-free mice by microbiome transplant from PGLYRP1-deficient mice.[43]

Cytotoxicity

Mouse PGLYRP1 (Tag7) was reported to be cytotoxic for tumor cells and to function as a Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α)-like cytokine.[7] Subsequent experiments revealed that PGLYRP1 (Tag7) by itself does not have cytotoxic activity,[12][45] but that PGLYRP1 (Tag7) forms a complex with heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and that only these complexes are cytotoxic for tumor cells,[45] whereas PGLYRP1 (Tag7) by itself acts as an antagonist of cytotoxicity of PGLYRP1-Hsp70 complexes.[46]

Interaction with host proteins and receptors

Human and mouse PGLYRP1 (Tag7) bind heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) in solution and PGLYRP1-Hsp70 complexes are also secreted by cytotoxic lymphocytes, and these complexes are cytotoxic for tumor cells.[45][47] This cytotoxicity is antagonized by metastasin (S100A4)[48] and heat shock-binding protein HspBP1.[49] PGLYRP1-Hsp70 complexes bind to the TNFR1 (tumor necrosis factor receptor-1, which is a death receptor) and induce a cytotoxic effect via apoptosis and necroptosis.[46] This cytotoxicity is associated with permeabilization of lysosomes and mitochondria.[50] By contrast, free PGLYRP1 acts as a TNFR1 antagonist by binding to TNFR1 and inhibiting its activation by PGLYRP1-Hsp70 complexes.[46] A peptide from human PGLYRP1 (amino acids 163-175) also inhibits the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α and PGLYRP1-Hsp70 complexes.[51]

Human PGLYRP1 complexed with peptidoglycan or multimerized binds to and stimulates TREM-1 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1), a receptor present on neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages that induces production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[52]

Medical relevance

Genetic PGLYRP1 variants or changed expression of PGLYRP1 are often associated with various diseases. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, have significantly more frequent missense variants in PGLYRP1 gene (and also in the other three PGLYRP genes) than healthy controls.[53] These results suggest that PGLYRP1 protects humans from these inflammatory diseases, and that mutations in PGLYRP1 gene are among the genetic factors predisposing to these diseases. PGLYRP1 variants are also associated with increased fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease.[54]

Several diseases are associated with increased expression of PGLYRP1, including: atherosclerosis,[55][56] myocardial infarction,[57] sepsis,[58] inflamed tissues in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis,[59] pulmonary fibrosis,[60] asthma,[61] chronic kidney disease,[62] rheumatoid arthritis,[63] gingival inflammation,[64][65][66][67][68] osteoarthritis,[69] cardiovascular events and death in kidney transplant patients,[70] alopecia,[71] heart failure,[72] type I diabetes,[73] infectious complications in hemodialysis,[74] and thrombosis,[75] consistent with pro-inflammatory effects of PGLYRP1. Lower expression of PGLYRP1 was found in endometriosis.[76]

See also

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000008438 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030413 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Kang D, Liu G, Lundström A, Gelius E, Steiner H (August 1998). "A peptidoglycan recognition protein in innate immunity conserved from insects to humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (17): 10078–82. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9510078K. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.17.10078. PMC 21464. PMID 9707603.

- "Entrez Gene: PGLYRP1 peptidoglycan recognition protein 1".

- Kiselev SL, Kustikova OS, Korobko EV, Prokhortchouk EB, Kabishev AA, Lukanidin EM, Georgiev GP (July 1998). "Molecular cloning and characterization of the mouse tag7 gene encoding a novel cytokine". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (29): 18633–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.29.18633. PMID 9660837. S2CID 11417742.

- "Pglyrp1 peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 [Mus musculus (house mouse)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- Liu C, Xu Z, Gupta D, Dziarski R (September 2001). "Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: a novel family of four human innate immunity pattern recognition molecules". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (37): 34686–94. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105566200. PMID 11461926. S2CID 44619852.

- Guan R, Wang Q, Sundberg EJ, Mariuzza RA (April 2005). "Crystal structure of human peptidoglycan recognition protein S (PGRP-S) at 1.70 A resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 347 (4): 683–91. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.070. PMID 15769462.

- Tydell CC, Yount N, Tran D, Yuan J, Selsted ME (May 2002). "Isolation, characterization, and antimicrobial properties of bovine oligosaccharide-binding protein. A microbicidal granule protein of eosinophils and neutrophils". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (22): 19658–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200659200. PMID 11880375. S2CID 904536.

- Liu C, Gelius E, Liu G, Steiner H, Dziarski R (August 2000). "Mammalian peptidoglycan recognition protein binds peptidoglycan with high affinity, is expressed in neutrophils, and inhibits bacterial growth". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (32): 24490–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M001239200. PMID 10827080. S2CID 24226481.

- Dziarski R, Platt KA, Gelius E, Steiner H, Gupta D (July 2003). "Defect in neutrophil killing and increased susceptibility to infection with nonpathogenic gram-positive bacteria in peptidoglycan recognition protein-S (PGRP-S)-deficient mice". Blood. 102 (2): 689–97. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-12-3853. PMID 12649138.

- Cho JH, Fraser IP, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Fujimoto Y, Stahl GL, Ezekowitz RA (October 2005). "Human peptidoglycan recognition protein S is an effector of neutrophil-mediated innate immunity". Blood. 106 (7): 2551–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-02-0530. PMC 1895263. PMID 15956276.

- Park SY, Jing X, Gupta D, Dziarski R (April 2013). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 enhances experimental asthma by promoting Th2 and Th17 and limiting regulatory T cell and plasmacytoid dendritic cell responses". Journal of Immunology. 190 (7): 3480–92. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1202675. PMC 3608703. PMID 23420883.

- Yao X, Gao M, Dai C, Meyer KS, Chen J, Keeran KJ, et al. (December 2013). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 promotes house dust mite-induced airway inflammation in mice". American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 49 (6): 902–11. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2013-0001OC. PMC 3931111. PMID 23808363.

- Kappeler SR, Heuberger C, Farah Z, Puhan Z (August 2004). "Expression of the peptidoglycan recognition protein, PGRP, in the lactating mammary gland". Journal of Dairy Science. 87 (8): 2660–8. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73392-5. PMID 15328291.

- Ghosh A, Lee S, Dziarski R, Chakravarti S (September 2009). "A novel antimicrobial peptidoglycan recognition protein in the cornea". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 50 (9): 4185–91. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-3040. PMC 3052780. PMID 19387073.

- Park SY, Gupta D, Hurwich R, Kim CH, Dziarski R (December 2011). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein Pglyrp2 protects mice from psoriasis-like skin inflammation by promoting regulatory T cells and limiting Th17 responses". Journal of Immunology. 187 (11): 5813–23. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101068. PMC 3221838. PMID 22048773.

- Park SY, Gupta D, Kim CH, Dziarski R (2011). "Differential effects of peptidoglycan recognition proteins on experimental atopic and contact dermatitis mediated by Treg and Th17 cells". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e24961. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624961P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024961. PMC 3174980. PMID 21949809.

- Saha S, Jing X, Park SY, Wang S, Li X, Gupta D, Dziarski R (August 2010). "Peptidoglycan recognition proteins protect mice from experimental colitis by promoting normal gut flora and preventing induction of interferon-gamma". Cell Host & Microbe. 8 (2): 147–62. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2010.07.005. PMC 2998413. PMID 20709292.

- Lo D, Tynan W, Dickerson J, Mendy J, Chang HW, Scharf M, et al. (July 2003). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein expression in mouse Peyer's Patch follicle associated epithelium suggests functional specialization". Cellular Immunology. 224 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00155-2. PMID 14572796.

- Wang J, Gusti V, Saraswati A, Lo DD (November 2011). "Convergent and divergent development among M cell lineages in mouse mucosal epithelium". Journal of Immunology. 187 (10): 5277–85. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1102077. PMC 3208058. PMID 21984701.

- Downs-Canner S, Berkey S, Delgoffe GM, Edwards RP, Curiel T, Odunsi K, et al. (March 2017). "reg cells". Nature Communications. 8: 14649. doi:10.1038/ncomms14649. PMC 5355894. PMID 28290453.

- Arentsen T, Qian Y, Gkotzis S, Femenia T, Wang T, Udekwu K, et al. (February 2017). "The bacterial peptidoglycan-sensing molecule Pglyrp2 modulates brain development and behavior". Molecular Psychiatry. 22 (2): 257–266. doi:10.1038/mp.2016.182. PMC 5285465. PMID 27843150.

- Rehman A, Taishi P, Fang J, Majde JA, Krueger JM (January 2001). "The cloning of a rat peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) and its induction in brain by sleep deprivation". Cytokine. 13 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1006/cyto.2000.0800. PMID 11145837.

- Lang MF, Schneider A, Krüger C, Schmid R, Dziarski R, Schwaninger M (January 2008). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein-S (PGRP-S) is upregulated by NF-kappaB". Neuroscience Letters. 430 (2): 138–41. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.027. PMID 18035491. S2CID 54406942.

- Tydell CC, Yuan J, Tran P, Selsted ME (January 2006). "Bovine peptidoglycan recognition protein-S: antimicrobial activity, localization, secretion, and binding properties". Journal of Immunology. 176 (2): 1154–62. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1154. PMID 16394004. S2CID 11173657.

- De Marzi MC, Todone M, Ganem MB, Wang Q, Mariuzza RA, Fernández MM, Malchiodi EL (July 2015). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein-peptidoglycan complexes increase monocyte/macrophage activation and enhance the inflammatory response". Immunology. 145 (3): 429–42. doi:10.1111/imm.12460. PMC 4479541. PMID 25752767.

- Wang ZM, Li X, Cocklin RR, Wang M, Wang M, Fukase K, et al. (December 2003). "Human peptidoglycan recognition protein-L is an N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (49): 49044–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M307758200. PMID 14506276. S2CID 35373818.

- Lu X, Wang M, Qi J, Wang H, Li X, Gupta D, Dziarski R (March 2006). "Peptidoglycan recognition proteins are a new class of human bactericidal proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (9): 5895–907. doi:10.1074/jbc.M511631200. PMID 16354652. S2CID 21943426.

- Sharma P, Singh N, Sinha M, Sharma S, Perbandt M, Betzel C, et al. (May 2008). "Crystal structure of the peptidoglycan recognition protein at 1.8 A resolution reveals dual strategy to combat infection through two independent functional homodimers". Journal of Molecular Biology. 378 (4): 923–32. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.018. PMID 18395744.

- Wang M, Liu LH, Wang S, Li X, Lu X, Gupta D, Dziarski R (March 2007). "Human peptidoglycan recognition proteins require zinc to kill both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and are synergistic with antibacterial peptides". Journal of Immunology. 178 (5): 3116–25. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3116. PMID 17312159. S2CID 22160694.

- "Reactome | PGLYRP1 binds bacterial peptidoglycan". reactome.org. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- Kumar S, Roychowdhury A, Ember B, Wang Q, Guan R, Mariuzza RA, Boons GJ (November 2005). "Selective recognition of synthetic lysine and meso-diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan fragments by human peptidoglycan recognition proteins I{alpha} and S". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (44): 37005–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506385200. PMID 16129677. S2CID 44913130.

- Sharma P, Dube D, Sinha M, Mishra B, Dey S, Mal G, et al. (September 2011). "Multiligand specificity of pathogen-associated molecular pattern-binding site in peptidoglycan recognition protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (36): 31723–30. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.264374. PMC 3173064. PMID 21784863.

- Sharma P, Dube D, Singh A, Mishra B, Singh N, Sinha M, et al. (May 2011). "Structural basis of recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines by camel peptidoglycan recognition protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (18): 16208–17. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.228163. PMC 3091228. PMID 21454594.

- Kashyap DR, Wang M, Liu LH, Boons GJ, Gupta D, Dziarski R (June 2011). "Peptidoglycan recognition proteins kill bacteria by activating protein-sensing two-component systems". Nature Medicine. 17 (6): 676–83. doi:10.1038/nm.2357. PMC 3176504. PMID 21602801.

- Bobrovsky P, Manuvera V, Polina N, Podgorny O, Prusakov K, Govorun V, Lazarev V (July 2016). "Recombinant Human Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins Reveal Antichlamydial Activity". Infection and Immunity. 84 (7): 2124–2130. doi:10.1128/IAI.01495-15. PMC 4936355. PMID 27160295.

- Wang J, Feng Y, Wang C, Srinivas S, Chen C, Liao H, et al. (July 2017). "Pathogenic Streptococcus strains employ novel escape strategy to inhibit bacteriostatic effect mediated by mammalian peptidoglycan recognition protein". Cellular Microbiology. 19 (7): e12724. doi:10.1111/cmi.12724. PMID 28092693. S2CID 3534029.

- Osanai A, Sashinami H, Asano K, Li SJ, Hu DL, Nakane A (February 2011). "Mouse peptidoglycan recognition protein PGLYRP-1 plays a role in the host innate immune response against Listeria monocytogenes infection". Infection and Immunity. 79 (2): 858–66. doi:10.1128/IAI.00466-10. PMC 3028829. PMID 21134971.

- Dziarski R, Park SY, Kashyap DR, Dowd SE, Gupta D (2016). "Pglyrp-Regulated Gut Microflora Prevotella falsenii, Parabacteroides distasonis and Bacteroides eggerthii Enhance and Alistipes finegoldii Attenuates Colitis in Mice". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0146162. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1146162D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146162. PMC 4699708. PMID 26727498.

- Banskar S, Detzner AA, Juarez-Rodriguez MD, Hozo I, Gupta D, Dziarski R (December 2019). "Pglyrp1-Regulated Microbiome Enhances Experimental Allergic Asthma". Journal of Immunology. 203 (12): 3113–3125. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1900711. PMID 31704882. S2CID 207942798.

- Saha S, Qi J, Wang S, Wang M, Li X, Kim YG, et al. (February 2009). "PGLYRP-2 and Nod2 are both required for peptidoglycan-induced arthritis and local inflammation". Cell Host & Microbe. 5 (2): 137–50. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.010. PMC 2671207. PMID 19218085.

- Sashchenko LP, Dukhanina EA, Yashin DV, Shatalov YV, Romanova EA, Korobko EV, et al. (January 2004). "Peptidoglycan recognition protein tag7 forms a cytotoxic complex with heat shock protein 70 in solution and in lymphocytes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (3): 2117–24. doi:10.1074/jbc.M307513200. PMID 14585845. S2CID 23485070.

- Yashin DV, Ivanova OK, Soshnikova NV, Sheludchenkov AA, Romanova EA, Dukhanina EA, et al. (August 2015). "Tag7 (PGLYRP1) in Complex with Hsp70 Induces Alternative Cytotoxic Processes in Tumor Cells via TNFR1 Receptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (35): 21724–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.639732. PMC 4571894. PMID 26183779.

- Sashchenko LP, Dukhanina EA, Shatalov YV, Yashin DV, Lukyanova TI, Kabanova OD, et al. (September 2007). "Cytotoxic T lymphocytes carrying a pattern recognition protein Tag7 can detect evasive, HLA-negative but Hsp70-exposing tumor cells, thereby ensuring FasL/Fas-mediated contact killing". Blood. 110 (6): 1997–2004. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064444. PMID 17551095.

- Dukhanina EA, Kabanova OD, Lukyanova TI, Shatalov YV, Yashin DV, Romanova EA, et al. (August 2009). "Opposite roles of metastasin (S100A4) in two potentially tumoricidal mechanisms involving human lymphocyte protein Tag7 and Hsp70". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (33): 13963–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10613963D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900116106. PMC 2729003. PMID 19666596.

- Yashin DV, Dukhanina EA, Kabanova OD, Romanova EA, Lukyanova TI, Tonevitskii AG, et al. (March 2011). "The heat shock-binding protein (HspBP1) protects cells against the cytotoxic action of the Tag7-Hsp70 complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (12): 10258–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.163436. PMC 3060480. PMID 21247889.

- Yashin DV, Romanova EA, Ivanova OK, Sashchenko LP (April 2016). "The Tag7-Hsp70 cytotoxic complex induces tumor cell necroptosis via permeabilisation of lysosomes and mitochondria". Biochimie. 123: 32–6. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2016.01.007. PMID 26796882.

- Romanova EA, Sharapova TN, Telegin GB, Minakov AN, Chernov AS, Ivanova OK, et al. (February 2020). "A 12-mer Peptide of Tag7 (PGLYRP1) Forms a Cytotoxic Complex with Hsp70 and Inhibits TNF-Alpha Induced Cell Death". Cells. 9 (2): 488. doi:10.3390/cells9020488. PMC 7072780. PMID 32093269.

- Read CB, Kuijper JL, Hjorth SA, Heipel MD, Tang X, Fleetwood AJ, et al. (February 2015). "Cutting Edge: identification of neutrophil PGLYRP1 as a ligand for TREM-1". Journal of Immunology. 194 (4): 1417–21. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1402303. PMC 4319313. PMID 25595774.

- Zulfiqar F, Hozo I, Rangarajan S, Mariuzza RA, Dziarski R, Gupta D (2013). "Genetic Association of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein Variants with Inflammatory Bowel Disease". PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e67393. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...867393Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067393. PMC 3686734. PMID 23840689.

- Nkya S, Mwita L, Mgaya J, Kumburu H, van Zwetselaar M, Menzel S, et al. (June 2020). "Identifying genetic variants and pathways associated with extreme levels of fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease in Tanzania". BMC Medical Genetics. 21 (1): 125. doi:10.1186/s12881-020-01059-1. PMC 7275552. PMID 32503527.

- Rohatgi A, Ayers CR, Khera A, McGuire DK, Das SR, Matulevicius S, et al. (April 2009). "The association between peptidoglycan recognition protein-1 and coronary and peripheral atherosclerosis: Observations from the Dallas Heart Study". Atherosclerosis. 203 (2): 569–75. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.015. PMID 18774573.

- Brownell NK, Khera A, de Lemos JA, Ayers CR, Rohatgi A (May 2016). "Association Between Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein-1 and Incident Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Events: The Dallas Heart Study". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 67 (19): 2310–2312. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.063. PMID 27173041.

- Park HJ, Noh JH, Eun JW, Koh YS, Seo SM, Park WS, et al. (May 2015). "Assessment and diagnostic relevance of novel serum biomarkers for early decision of ST-elevation myocardial infarction". Oncotarget. 6 (15): 12970–83. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.4001. PMC 4536992. PMID 26025919.

- Zhang J, Cheng Y, Duan M, Qi N, Liu J (May 2017). "Unveiling differentially expressed genes upon regulation of transcription factors in sepsis". 3 Biotech. 7 (1): 46. doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0713-x. PMC 5428098. PMID 28444588.

- Brynjolfsson SF, Magnusson MK, Kong PL, Jensen T, Kuijper JL, Håkansson K, et al. (August 2016). "An Antibody Against Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 1 (TREM-1) Dampens Proinflammatory Cytokine Secretion by Lamina Propria Cells from Patients with IBD". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 22 (8): 1803–11. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000822. PMID 27243593. S2CID 3637291.

- Molyneaux PL, Willis-Owen SA, Cox MJ, James P, Cowman S, Loebinger M, et al. (June 2017). "Host-Microbial Interactions in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 195 (12): 1640–1650. doi:10.1164/rccm.201607-1408OC. PMC 5476909. PMID 28085486.

- Kasaian MT, Lee J, Brennan A, Danto SI, Black KE, Fitz L, Dixon AE (July 2018). "Proteomic analysis of serum and sputum analytes distinguishes controlled and poorly controlled asthmatics". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 48 (7): 814–824. doi:10.1111/cea.13151. PMID 29665127. S2CID 4938216.

- Nylund KM, Ruokonen H, Sorsa T, Heikkinen AM, Meurman JH, Ortiz F, et al. (January 2018). "Association of the salivary triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells/its ligand peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 axis with oral inflammation in kidney disease". Journal of Periodontology. 89 (1): 117–129. doi:10.1902/jop.2017.170218. PMID 28846062. S2CID 21830535.

- Luo Q, Li X, Zhang L, Yao F, Deng Z, Qing C, et al. (January 2019). "Serum PGLYRP‑1 is a highly discriminatory biomarker for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis". Molecular Medicine Reports. 19 (1): 589–594. doi:10.3892/mmr.2018.9632. PMID 30431075.

- Silbereisen A, Hallak AK, Nascimento GG, Sorsa T, Belibasakis GN, Lopez R, Bostanci N (October 2019). "Regulation of PGLYRP1 and TREM-1 during Progression and Resolution of Gingival Inflammation". JDR Clinical and Translational Research. 4 (4): 352–359. doi:10.1177/2380084419844937. PMID 31013451. S2CID 129941967.

- Raivisto T, Heikkinen AM, Silbereisen A, Kovanen L, Ruokonen H, Tervahartiala T, et al. (October 2020). "Regulation of Salivary Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein 1 in Adolescents". JDR Clinical and Translational Research. 5 (4): 332–341. doi:10.1177/2380084419894287. PMID 31860804.

- Yucel ZP, Silbereisen A, Emingil G, Tokgoz Y, Kose T, Sorsa T, et al. (October 2020). "Salivary biomarkers in the context of gingival inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis". Journal of Periodontology. 91 (10): 1339–1347. doi:10.1002/JPER.19-0415. PMID 32100289.

- Karsiyaka Hendek M, Kisa U, Olgun E (January 2020). "The effect of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid peptidoglycan recognition protein-1 level following initial periodontal therapy in chronic periodontitis". Oral Diseases. 26 (1): 166–172. doi:10.1111/odi.13207. PMID 31587460.

- Teixeira MK, Lira-Junior R, Lourenço EJ, Telles DM, Boström EA, Figueredo CM, Bostanci N (May 2020). "The modulation of the TREM-1/PGLYRP1/MMP-8 axis in peri-implant diseases". Clinical Oral Investigations. 24 (5): 1837–1844. doi:10.1007/s00784-019-03047-z. PMID 31444693. S2CID 201283050.

- Yang Z, Ni J, Kuang L, Gao Y, Tao S (September 2020). "Identification of genes and pathways associated with subchondral bone in osteoarthritis via bioinformatic analysis". Medicine. 99 (37): e22142. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000022142. PMC 7489699. PMID 32925767.

- Ortiz F, Nylund KM, Ruokonen H, Meurman JH, Furuholm J, Bostanci N, Sorsa T (August 2020). "Salivary Biomarkers of Oral Inflammation Are Associated With Cardiovascular Events and Death Among Kidney Transplant Patients". Transplantation Proceedings. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2020.07.007. PMID 32768288.

- Glickman JW, Dubin C, Renert-Yuval Y, Dahabreh D, Kimmel GW, Auyeung K, et al. (May 2020). "Cross-sectional study of blood biomarkers of patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata reveals systemic immune and cardiovascular biomarker dysregulation". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.138. PMID 32376430.

- Klimczak-Tomaniak D, Bouwens E, Schuurman AS, Akkerhuis KM, Constantinescu A, Brugts J, et al. (June 2020). "Temporal patterns of macrophage- and neutrophil-related markers are associated with clinical outcome in heart failure patients". ESC Heart Failure. 7 (3): 1190–1200. doi:10.1002/ehf2.12678. PMC 7261550. PMID 32196993.

- Yang S, Cao C, Xie Z, Zhou Z (March 2020). "Analysis of potential hub genes involved in the pathogenesis of Chinese type 1 diabetic patients". Annals of Translational Medicine. 8 (6): 295. doi:10.21037/atm.2020.02.171. PMC 7186604. PMID 32355739.

- Arenius I, Ruokonen H, Ortiz F, Furuholm J, Välimaa H, Bostanci N, et al. (July 2020). "The relationship between oral diseases and infectious complications in patients under dialysis". Oral Diseases. 26 (5): 1045–1052. doi:10.1111/odi.13296. PMID 32026534.

- Guo C, Li Z (December 2019). "Bioinformatics Analysis of Key Genes and Pathways Associated with Thrombosis in Essential Thrombocythemia". Medical Science Monitor. 25: 9262–9271. doi:10.12659/MSM.918719. PMC 6911306. PMID 31801935.

- Grande G, Vincenzoni F, Milardi D, Pompa G, Ricciardi D, Fruscella E, et al. (2017). "Cervical mucus proteome in endometriosis". Clinical Proteomics. 14: 7. doi:10.1186/s12014-017-9142-4. PMC 5290661. PMID 28174513.

Further reading

- Dziarski R, Royet J, Gupta D (2016). "Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins and Lysozyme.". In Ratcliffe MJ (ed.). Encyclopedia of Immunobiology. 2. Elsevier Ltd. pp. 389–403. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-374279-7.02022-1. ISBN 978-0123742797.

- Royet J, Gupta D, Dziarski R (November 2011). "Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: modulators of the microbiome and inflammation". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 11 (12): 837–51. doi:10.1038/nri3089. PMID 22076558. S2CID 5266193.

- Royet J, Dziarski R (April 2007). "Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: pleiotropic sensors and effectors of antimicrobial defences". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 5 (4): 264–77. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1620. PMID 17363965. S2CID 39569790.

- Dziarski R, Gupta D (2006). "The peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs)". Genome Biology. 7 (8): 232. doi:10.1186/gb-2006-7-8-232. PMC 1779587. PMID 16930467.

- Bastos PA, Wheeler R, Boneca IG (September 2020). "Uptake, recognition and responses to peptidoglycan in the mammalian host". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuaa044. PMID 32897324.

- Wolf AJ, Underhill DM (April 2018). "Peptidoglycan recognition by the innate immune system". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 18 (4): 243–254. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.136. PMID 29292393. S2CID 3894187.

- Laman JD, 't Hart BA, Power C, Dziarski R (July 2020). "Bacterial Peptidoglycan as a Driver of Chronic Brain Inflammation". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 26 (7): 670–682. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2019.11.006. PMID 32589935.

- Gonzalez-Santana A, Diaz Heijtz R (August 2020). "Bacterial Peptidoglycans from Microbiota in Neurodevelopment and Behavior". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 26 (8): 729–743. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2020.05.003. PMID 32507655.