Pendennis Castle

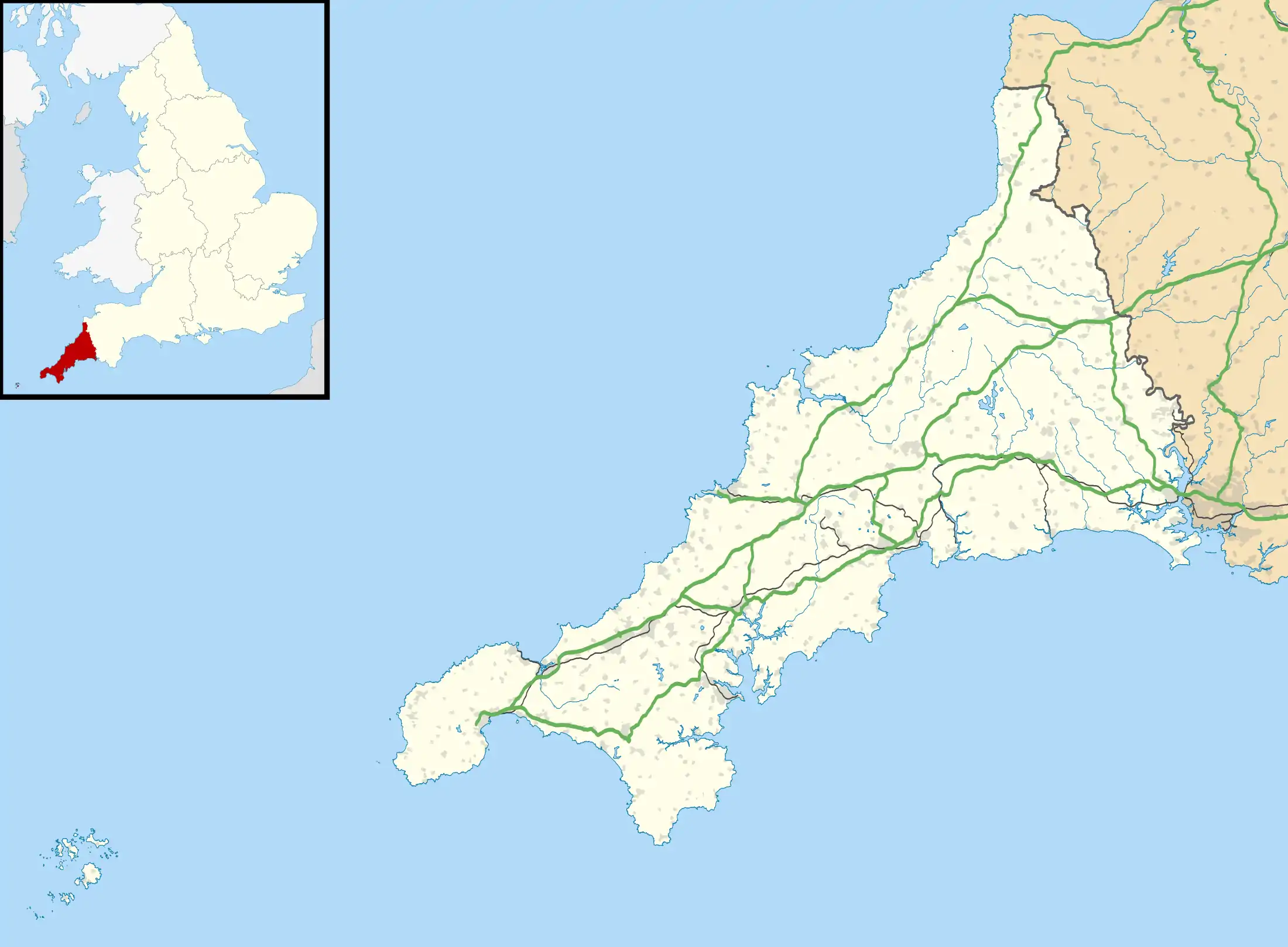

Pendennis Castle (Cornish: Penn Dinas, meaning "headland fortification") is an artillery fort constructed by Henry VIII near Falmouth, Cornwall, England between 1540 and 1542. It formed part of the King's Device programme to protect against invasion from France and the Holy Roman Empire, and defended the Carrick Roads waterway at the mouth of the River Fal. The original, circular keep and gun platform was expanded at the end of the century to cope with the increasing Spanish threat, with a ring of extensive stone ramparts and bastions built around the older castle. Pendennis saw service during the English Civil War, when it was held by the Royalists, and was only taken by Parliament after a long siege in 1646. It survived the interregnum and Charles II renovated the fortress after his restoration to the throne in 1660.

| Pendennis Castle | |

|---|---|

Kastell Penn Dinas | |

| Falmouth, Cornwall, England | |

16th-century keep and gun platform | |

Pendennis Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50°08′50″N 5°02′52″W |

| Type | Device Fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1540–42 |

| Built by | John Killigrew |

| Events | English Civil War Second World War |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Pendennis Castle |

| Designated | 23 January 1973 |

| Reference no. | 1270096 |

Ongoing concerns about a possible French invasion resulted in Pendennis's defences being modernised and upgraded in the 1730s and again during the 1790s; during the Napoleonic Wars, the castle held up to 48 guns. In the 1880s and 1890s an electrically operated minefield was laid across the River Fal, operated from Pendennis and St Mawes, and new, quick-firing guns were installed to support these defences. The castle was rearmed during the First World War but saw no action and was rearmed again during the Second World War when it saw action against the German Luftwaffe aircraft, but in 1956, by now obsolete, it was decommissioned. It passed into the control of the Ministry of Works, who cleared away many of the more modern military buildings and opened the site to visitors. In the 21st century, the castle is managed by English Heritage as a tourist attraction, receiving 74,230 visitors in 2011–12.[1] The heritage agency Historic England considers Pendennis to be "one of the finest examples of a post-medieval defensive promontory fort in the country".[2]

History

Construction

Pendennis Castle was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.[3] Basic defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.[4]

In 1533, Henry broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon and remarry.[5] Catherine was the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, and he took the annulment as a personal insult.[6] This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraging the two countries to attack England.[7] An invasion of England appeared certain.[8] In response, Henry issued an order, called a "device", in 1539, giving instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" and the construction of forts along the English coastline.[9]

The stretch of water known as Carrick Roads at the mouth of the River Fal was an important anchorage serving shipping arriving from the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.[10] A small gun tower, called the Little Dennis Blockhouse, was built in 1539 overlooking the entrance, and plans were made to protect the anchorage further with five additional castles.[11] In the event, only two of these were constructed, Pendennis and St Mawes Castle, positioned on each side of Carrick Roads and able to provide overlapping fire across the water.[12] John Killigrew, a prominent member of the local Cornish gentry, probably oversaw the construction of Pendennis; it was built on his land and he was appointed as its first captain.[13] Pendennis Castle cost £5,614 to construct.[14][lower-alpha 1]

Initial operation

The Killigrews controlled the castle for several decades, with John Killigrew's son and grandson continuing in turn as the captain there until 1605.[16] The captains of Pendennis frequently argued with those of St Mawes and in 1630 a legal dispute broke out about the rights to search and detain incoming shipping: both castles argued that they had a traditional right to do so.[17] The Admiralty eventually issued a compromise, proposing that the castles share the searching of the traffic.[18]

Meanwhile, a lasting peace with France was made in 1558 and the initial invasion threat passed.[19] The Spanish threat to the south-west of England became more serious, however, and war broke out in 1569.[20] As a result, a defensive earthwork was constructed north-west of the castle to protect it against an attack from the land, and an additional gun battery facing upriver was installed alongside the blockhouse.[21] The levels of the garrison varied considerably during the period.[22] Pendennis had a garrison of 100 men in 1578, and could have mustered around 500 men in 1596, while in 1599 it was reportedly guarded by 200 soldiers.[22]

The Spanish threat continued; raiding parties destroyed the Killigrews' family home at Arwenack in 1593, and four Spanish ships attacked the towns along the coast in 1595.[23] In 1597 a Spanish fleet with 20,000 men set out to assault Pendennis and invade England, only being prevented from landing by bad weather.[24] The failed attack caused considerable concern inside government and the Privy Council were informed that the castle was not sufficient to prevent a Spanish landing along the coast.[25] A subsequent review carried out by Sir Nicholas Parker, Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Ferdinando Gorges recommended that the castle's defences should be significantly extended.[26] The military engineer Paul Ive constructed an Italian-styled ring of earthworks, embrasures, bastions and a stone-revetted ditch around the original Henrician castle between 1597 and 1600, using a team of 400 local workers, costing around £80 a week in wages.[27][lower-alpha 1]

In the early 1600s England was at peace and Pendennis was neglected; reportedly the garrison's pay was two years in arrears, forcing them to gather limpets from the shoreline for food.[28] Nonetheless, a new Italian-styled gatehouse was added to the castle, probably in 1611.[29] War with Spain broke out again 1624 and a new defensive line, with bastions and artillery, was built across the peninsula in 1627.[26]

English Civil War and Restoration

When civil war broke out in 1642 between King Charles I and Parliament, Pendennis and the south-west of England were held by the Royalists.[30] The growing town of Falmouth was a strategically important part of their supply route to the Continent, while Carrick Roads formed a base for Royalist piracy in the English Channel.[30] As the war turned in favour of the Parliamentarians, preparations were made for Prince Charles to shelter there over the winter of 1645–46, as part of which the surrounding fortifications were improved; in the event, Charles stayed in the castle only briefly in early 1646.[30]

Shortly after Charles left Pendennis for the Isles of Scilly on 2 March, Thomas Fairfax entered Cornwall with a substantial army.[30] Almost all the other Royalist positions in England had by now fallen and St Mawes Castle surrendered immediately as Fairfax approached.[30] Pendennis Castle, however, continued to hold out, defended by around 1,000 soldiers under the command of Sir John Arundell.[30] They were determined to hold out against the besiegers and Arundell announced that he would die rather than surrender.[31] Two Parliamentary colonels, Fortescue and Hammond, directed the bombardment of the castle from the land, while Captain Batten, with a flotilla of ten ships, blockaded it by sea, preventing fresh supplies from arriving.[32]

The garrison's defences were supported with artillery fire from a Royalist warship that was deliberately run aground north of the castle to produce an additional gun platform.[33] By July, food had begun to run short and some of the garrison unsuccessfully attempted to break out by sea to acquire supplies.[34] Arundell agreed to an honourable surrender on 15 August, and around 900 survivors left the fort two days later, some terminally ill from malnutrition.[35] Pendennis was the penultimate Royalist fortification to hold out in the war.[36]

Parliament maintained a garrison at the castle, but in 1647 it cut the levels of the armed forces across the country; most soldiers who lost their posts were offered two months pay, but at Pendennis only one month's pay was offered.[37] The garrison, led by Colonel Richard Fortescue, mutinied, seized the visiting Parliamentary commissioners and refused to leave the castle until the additional pay was granted to them.[38] Fearing a wider uprising, Parliament negotiated an end to the confrontation, paying off the garrison in full and offering Fortescue fresh employment elsewhere.[39] A smaller, more reliable garrison was then installed.[40] During the interregnum, the castle was used to imprison the radical pamphleteer William Prynne.[41]

Just before the restoration of King Charles II to the throne in 1660, the Royalist Sir Peter Killigrew became the new captain of the castle.[29] Fears of an invasion continued, and an additional gun battery was constructed at Crab Quay, to the south-east of the main fortification.[34] At the end of the century, a new guard barracks and gate were constructed, probably emulating those being constructed in France.[34]

18th–19th centuries

Pendennis Castle continued in use through the 18th and 19th centuries under the command of successive captains, still operating in partnership with St Mawes. In 1714, Colonel Christian Lilly carried out an inspection of the fortification, finding it to be "in a very precarious condition" and noting that "the body of the fort having been for many years neglected is now is in a very ruinous condition".[42] The parapets had collapsed, the ramparts could easily be scaled and the ditches were filled with brambles.[43] Little was done to remedy this, however, until the 1730s, when the castle was extensively modernised.[42] The interior was redesigned, the ramparts were rebuilt and the castle's guns were replaced, incorporating new 18-pounder cannons.[42]

During the American Revolutionary War, France allied itself with the revolutionaries, causing war with Britain to break out in 1778.[44] The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars followed, during which period Falmouth became an important military depot.[44] In 1795, the Crown purchased the castle's land from the Killigrew family, and reinforced the fortress to deal with the fresh threat of invasion.[45] The government installed more guns and built a new gun position called the Half-Moon Battery just outside the 16th-century walls; the landward defences of Pendennis were reinforced, and a new barracks and other ancillary buildings were built inside the fortress.[46] At its peak, the castle was equipped with up to 48 artillery pieces.[44] A new volunteer unit of artillery was formed in Falmouth to support the forts around the harbour, many of them carrying out training using Pendennis's guns before then deploying elsewhere across Cornwall.[47]

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Pendennis was neglected; many of its guns became unserviceable and some buildings fell into ruin.[48] The old post of captain of Pendennis Castle was abolished in 1837, with the fortification commanded by a conventional military appointment.[49] In the 1850s, renewed fears of a French invasion led to investment in new artillery at the castle, and nineteen 32- and 56-pounder (14.5 and 24.5 kg) guns were installed.[48] Falmouth continued to be an important harbour, particularly for the Royal Navy.[50] When new concerns about France emerged, an electronically operated minefield was laid across Carrick Roads in 1885, jointly controlled from Pendennis and St Mawes.[51] New 6- and 12-pounder (2.7 and 5.4 kg) quick-firing guns, supported by machine-guns for close defence, were assigned to the castle to deal with the emerging threat from enemy torpedo boats.[50]

20th–21st centuries

The 105th Regiment Royal Garrison Artillery took over the manning of Pendennis Castle in 1902.[50] A new barracks was built to house them, and a signal station was constructed on top of the old keep to coordinate operations with shipping, while the 16th-century guardhouse alongside the keep was demolished.[52] The castle was reinforced by territorial soldiers during the First World War and additional defences were constructed on the landward side.[53] It continued to defend the harbour and was also used for training purposes.[53] After the war, Pendennis continued to be used for training gunners, but its 16th-century buildings were placed into the guardianship of the Ministry of Works in 1920, and by 1939 the fortification's artillery had all been removed.[54]

The castle was rearmed at the beginning of the Second World War.[55] Twin 6-pounder guns and longer range artillery were installed, zig-zag trenches dug for protection, and new buildings added across the site.[55] The 16th-century fort was used as the headquarters of Falmouth Fire Command, which managed the artillery across the area.[56] New radar-controlled, 6-inch (152 mm) Mark 24 guns followed in 1943.[57] Falmouth played an important role in supporting the D-Day invasion of France in 1944, and during the preparations for the invasion, the gun batteries at Pendennis were used to defend against German E-boats.[57] After the war, Pendennis was initially still used for training, but the castle was now obsolete and it was decommissioned in 1956.[58]

The whole of the Pendennis site was placed in the guardianship of the Ministry of Works and opened to visitors; the Ministry focused its attention on the 16th-century castle and many of the more modern buildings were destroyed.[59] The barracks were used as a youth hostel between 1963 and 2000.[59] The heritage agency English Heritage took over control of the castle in 1984, and placed a greater priority on the conservation of its more modern features.[59] Extensive work was carried out across the castle in the 1990s to refurbish the fortifications and open new facilities for visitors, accompanied by archaeological surveys and excavations; in the 2000s, the sergeant's mess and the custodian's house were converted into holiday cottages.[60]

In the 21st century, the castle is managed by English Heritage as a tourist attraction, receiving 74,230 visitors in 2011–12.[1] It is protected under UK law as a grade I listed building and as a scheduled monument.[61]

Architecture

Pendennis Castle is located at the end of a peninsula, overlooking Carrick Roads and the sea.[62] It includes the original 16th-century Device Fort, surrounded by a ring of outer defences, based on the Elizabethan ramparts and later adapted during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.[63] Further gun batteries and a blockhouse are located closer to the shore.[63] The heritage agency Historic England considers Pendennis to be "one of the finest examples of a post-medieval defensive promontory fort in the country", demonstrating a long history of different defensive approaches, and English Heritage describes the site as "one of the finest surviving examples of a coast fortress in England".[64]

Ramparts

The gatehouse to the castle is located on the western side of the ramparts and dates from around 1700.[65] It has a classical facade, with a mid-19th century stone bridge reaching across the external ditch.[65] The ramparts are built from stone with protective ditches, and have angular bastions to provide overlapping fire, an innovative design in England when they were first constructed in 1600.[66] North of the gatehouse are the Smithwick and Carrick Mount bastions, the latter holding a quick-firing gun battery from 1903.[67] Further around the ramparts, the East Bastion also has two emplacements for quick-firing guns, dating from 1902, and underground magazines, which were converted into a battery plotting room in the Second World War.[68] Just to the south, the Nine-Gun Battery was built in the 1730s and comprises a fixed line of nine gun embrasures.[69]

In the south-east corner of the ramparts is the One-Gun Battery, which originally held a "disappearing gun", designed to pivot back under a steel shield when fired.[69] Built in 1895, the approach proved unsuccessful and the gun was removed in 1913, but the emplacement still remains and is a rare survival of this type of weapon.[70] The Bell Bastion, the Ravelin, the Pig's Pound Bastion and the Horse Pool Bastion protect the southern and western parts of the ramparts.[67] A range of artillery and anti-aircraft guns are on show around the defences, including 19th-century carronades, and 20th-century pieces such as a 155 mm (6.1 in) Long Tom field gun, a Quick Firing 3-inch 20 cwt (76 mm 102 kg) anti-aircraft gun and two Ordnance Quick-Firing 25-pounder (11 kg) howitzers.[71]

Inner castle

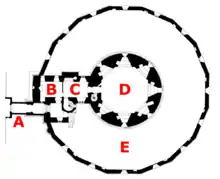

At the heart of the castle is the 16th-century Henrician fortification.[56] Built of a combination of granite ashlar and rubble, it comprises a circular keep surrounded by a gun platform, entered through a bridge and a forebuilding.[72] The keep has 3.36-metre (11.0 ft) thick walls and on in the inside is octagonal.[73] The basement was originally a kitchen, cellar and larder for the castle.[74] The ground floor was initially designed to be a gun room, complete with gun embrasures, but was altered during the initial construction project to form living accommodation for the garrison instead.[74] Another gun room occupies the first floor, with seven gun embrasures, and is dressed to appear as it would have done in the 16th century.[75] The roof has seven gun embrasures and a lookout turret.[76]

The polygonal gun platform around the keep has 16 sides, with a total of 14 gun embrasures.[77] The two-storey forebuilding dates from the second half of the 16th century, with three rooms on each level linked by a spiral-staircase, and was originally used to house the captain of the castle.[78] Its entrance was guarded with a portcullis, and the roof was designed to be defendable with handguns.[74] The stone bridge that stretches across the ditch that protects the castle dates from 1902; it would originally have been protected at the front by a rectangular gatehouse, but this was demolished at the start of the 20th century.[56]

The rest of the interior of the fortress was, at various times, occupied by a range of different military buildings, but they have mostly been demolished and grassed over to form a large parade ground.[79] Among the surviving buildings are the Royal Garrison Artillery barracks, located to the north of the parade ground. Built between 1900 and 1902, it could hold 140 soldiers in 12 man barrack-rooms.[80] Alongside the barracks are bungalows, originally for the use of senior non-commissioned officers, a storehouse dating from the Napoleonic Wars, and two guard barracks from 1700, which form a very early example of this form of military architecture in England.[81] Other buildings that have survived include a 19th-century field train shed, and an 18th-century gunpowder magazine, since converted into a shelter for gunners.[82]

External defences

Three defensive positions are positioned outside the main ramparts of the castle. To the south, reached by an underground passage, is the Half-Moon Battery, constructed in 1793 and redesigned in 1895 and 1941.[83] This has two camouflaged gun houses and 6-inch guns dating from the Second World War, when it held a team of 99 soldiers.[83] Further south, near the waterline, is the Little Dennis Blockhouse, a D-shaped gun position dating from 1539, altered in the 1540s and then adapted to form part of a larger fortification covering the whole of Pendennis Point in the late 16th century.[84] Built from Killas rubble, the exterior of the blockhouse and its lookout turret still survive intact.[85] Just along the shoreline to the north-east is the Crab Quay Battery, a set of defences originating in the 16th century, intended to prevent an amphibious landing on the headland, and modernised extensively in 1902.[84]

See also

Notes

- Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £5,614 in 1542 could be equivalent to between £2.8 million and £1,300 million, depending on the price comparison used. £80 in 1600 could be equivalent to between £15,700 and £5.1 million. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539 and 1547 came to £376,500, with St Mawes and Sandgate Castle, for example, costing ££5,018 and £5,584 apiece.[15]

References

- BDRC Continental (2011), "Visitor Attractions, Trends in England, 2010" (PDF), Visit England, p. 65, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015, retrieved 19 September 2015

- "Pendennis Peninsula Fortifications", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Thompson 1987, p. 111; Hale 1983, p. 63

- King 1991, pp. 176–177

- Morley 1976, p. 7

- Hale 1983, p. 63; Harrington 2007, p. 5

- Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, pp. 63–64

- Hale 1983, p. 66; Harrington 2007, p. 6

- Harrington 2007, p. 11; Walton 2010, p. 70

- Pattison 2009, p. 31; Jenkins 2007, p. 153

- Pattison 2009, pp. 15, 31; Jenkins 2007, p. 153

- Jenkins 2007, p. 153

- Pattison 2009, pp. 33–34

- Harrington 2007, p. 8

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12; Harrington 2007, p. 8; Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 18 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, p. 33

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 19; Oliver 1875, p. 86

- Oliver 1875, p. 90

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 40

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 40; Pattison 2009, p. 35

- Pattison 2009, p. 35

- Pattison 2009, p. 35; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10

- Pattison 2009, p. 35; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 9

- Pattison 2009, pp. 35, 38

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 9; Pattison 2009, p. 38

- Pattison 2009, p. 38

- Pattison 2009, p. 38; Oliver 1875, p. 17; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10

- Pattison 2009, p. 38; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10

- Pattison 2009, p. 39

- Pattison 2009, p. 39; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 11

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 11; Pattison 2009, p. 39

- Pattison 2009, pp. 39–40

- Pattison 2009, p. 40; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 11

- Pattison 2009, p. 40; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 12

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 12

- Stoyle 2000, pp. 39–40

- Stoyle 2000, pp. 39, 41

- Stoyle 2000, p. 41

- Stoyle 2000, p. 42

- Harrington 2003, p. 49

- Pattison 2009, p. 41

- Tomlinson 1973, p. 11

- Pattison 2009, p. 42

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10; Pattison 2009, pp. 42–43; Oliver 1875, p. 10

- Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10; Pattison 2009, pp. 42–43

- Maurice-Jones 2012, p. 102

- Pattison 2009, p. 43

- Oliver 1875, p. 78

- Pattison 2009, p. 44

- Jenkins 2007, p. 159; Pattison 2009, p. 44

- Pattison 2009, pp. 8, 44

- Pattison 2009, p. 47

- Pattison 2009, pp. 47–48; "Pendennis Castle" (PDF), English Heritage, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2015, retrieved 27 November 2015; Falmouth Conservation, p. 15

- Pattison 2009, p. 48; "Pendennis Peninsula Fortifications", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, p. 8

- Pattison 2009, p. 48

- Pattison 2009, p. 48; "Pendennis Castle" (PDF), English Heritage, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2015, retrieved 27 November 2015

- "Pendennis Castle" (PDF), English Heritage, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2015, retrieved 27 November 2015

- "Pendennis Castle" (PDF), English Heritage, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2015, retrieved 27 November 2015; "Research on Pendennis Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 21 December 2015

- "Pendennis Castle", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015; "Pendennis Peninsula Fortifications", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, pp. 4, 32

- Pattison 2009, pp. 4, 15

- "Pendennis Peninsula Fortifications", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015; "Significance of Pendennis Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, p. 5

- Pattison 2009, pp. 4, 15; "Significance of Pendennis Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, p. 49

- Pattison 2009, pp. 6–7

- Pattison 2009, p. 7

- Pattison 2009, p. 7; "Significance of Pendennis Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, pp. 14–15

- Pattison 2009, p. 8; "Pendennis Castle", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- "Pendennis Castle", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, p. 10

- Pattison 2009, pp. 10–11

- Pattison 2009, p. 11

- Pattison 2009, p. 12; "Pendennis Castle", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, pp. 8, 10; "Pendennis Castle", Historic England, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, p. 6

- Pattison 2009, pp. 5–6

- Pattison 2009, p. 5; "Significance of Pendennis Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 21 December 2015

- Pattison 2009, pp. 7, 12

- Pattison 2009, p. 14

- Pattison 2009, p. 15

- Pattison 2009, p. 15; "Little Dennis Blockhouse", Historic England, retrieved 10 May 2015

Bibliography

- Biddle, Martin; Hiller, Jonathon; Scott, Ian; Streeten, Anthony (2001). Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. ISBN 0904220230.

- Department of the Environment (1975). Pendennis and St Mawes Castles. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 886485719.

- Hale, John R. (1983). Renaissance War Studies. London, UK: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0907628176.

- Harrington, Peter (2003). English Civil War Fortifications 1642–51. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 9781472803979.

- Harrington, Peter (2007). The Castles of Henry VIII. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472803801.

- Jenkins, Stanley C. (2007). "St Mawes Castle, Cornwall". Fort. 35: 153–172.

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge Press. ISBN 9780415003506.

- Maurice-Jones, K. W. (2012) [1959]. The History of Coast Artillery in the British Army. Uckfield, UK: The Naval and Military Press. ISBN 9781781491157.

- Morley, B. M. (1976). Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defence. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0116707771.

- Oliver, Samuel Pasfield (1875). Pendennis and St Mawes: An Historical Sketch of Two Cornish Castles. Truro, UK: W. Lake. OCLC 23442843.

- Pattison, Paul (2009). Pendennis Castle and St Mawes Castle. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781848020221.

- Stoyle, Mark (2000). ""The Gear Rout": The Cornish Rising of 1648 and the Second Civil War". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 32 (1): 37–58. doi:10.2307/4053986. JSTOR 4053986.

- Thompson, M. W. (1987). The Decline of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1854226088.

- Tomlinson, Howard (1973). "The Ordnance Office and the King's Forts, 1660–1714". Architectural History. 16: 5–25. doi:10.2307/1568302. JSTOR 1568302.

- Walton, Steven A. (2010). "State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification". Osiris. 25 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1086/657263.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pendennis Castle. |

- English Heritage visitors' information

- Defending England's shores on Google Arts & Culture