Pascual Orozco

Pascual Orozco Vázquez, Jr. (in contemporary documents, sometimes spelled "Oroszco") (28 January 1882 – 30 August 1915) was a Mexican revolutionary leader who rose up to support Francisco I. Madero in late 1910 to depose long-time president Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911). Following Díaz's resignation in May 1911 and the democratic election of Madero in November 1911, Orozco revolted against the Madero government 16 months later. When Victoriano Huerta led a coup d'état against Madero in February 1913 that deposed Madero, Orozco joined the Huerta regime. Orozco's revolt against Madero had tarnished his revolutionary reputation and his subsequent support of Huerta compounded the repugnance against him.[1]

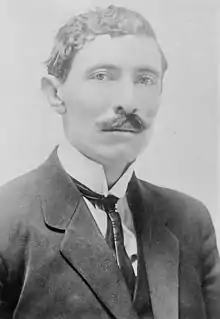

Pascual Orozco Vázquez, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Orozco circa 1913 | |

| Born | 28 January 1882 Santa Inés, Chihuahua, Mexico |

| Died | 30 August 1915 (aged 33) |

| Movement | Orozquistas in the Mexican Revolution |

Early life

Orozco was born to a middle-class family on Santa Inés hacienda near San Isidro, Guerrero, in the state of Chihuahua. His father was Pascual Orozco Sr.[2] His mother was Amada Orozco y Vázquez[2] (1852–1948); the Vázquez family were second-generation Basque immigrants.[3] The family was not rich, but had standing locally, where his father ran a village store and was a minor office holder.[4] Pascual Jr. was educated in the local public school and began working as a muleteer,[5] a hands-on job that was a vital link in transporting goods in northern Mexico and as a revolutionary gave him intimate knowledge of the terrain. Orozco, like fellow northern revolutionary Pancho Villa, worked a stint with foreign owned mining companies.[6]

Becoming a revolutionary

In the mountainous region of Chihuahua, "the outstanding leader in 1910-11 was Pascual Orozco, a tall, powerful, taciturn young man." He quickly rose to prominence once he had been recruited by Abraham González to the cause of Francisco I. Madero. Orozco was not so much a hard-line opponent of Porfirio Díaz, but rather the local strong man Joaquín Chávez, a client of the major power holder in Chihuahua, the Creel-Terrazas Family. One of his first actions after an early battle was to ransack Chávez's house.[7]

On 31 October of that year, Orozco was placed in command of the revolutionary forces in Guerrero municipality. He led his forces to a series of victories against Díaz loyalists, and by the end of the year most of the state was in the hands of the revolutionaries. At this point, Orozco was a hero in Chihuahua, with over 30,000 people lining the streets upon his return. Madero promoted him to colonel, and in March 1911 to brigadier general. These promotions were earned without any kind of military knowledge or military training.

_Pascual_Orozco._(21879503251).jpg.webp)

On 31 October 1910 he was named jefe revolucionario (revolutionary leader) of the Porfirio Díaz Anti Re-election Club in Guerrero District. A week after the beginning of the war, he obtained his first victory, against General Juan Navarro. After ambushing the federal troops in Cañón del Mal Paso on 2 January 1911, he ordered the dead soldiers stripped and sent the uniforms to Presidente Díaz with a note that read, "Ahí te van las hojas, mándame más tamales". ("Here are the wrappers, send me more tamales.")[8]

On 10 May 1911 Orozco and colonel Pancho Villa seized Ciudad Juárez, against Madero's orders.[9] For revolutionaries who had fought for the overthrow of Díaz, the victory at Ciudad Juárez that forced Díaz to resign the presidency was sweet. However, dismaying the revolutionaries who had defeated the Federal Army, Madero entered into negotiations with the Díaz regime for a transfer of power that dismayed revolutionary fighters. The Treaty of Ciudad Juárez stipulated the resignations of Díaz and his vice president, allowing them to go into exile; the establishment of an Interim Presidency under Francisco León de la Barra, a diplomat and lawyer who was not part of the Díaz inner circle. Most galling was that the treaty kept the Federal Army intact and called for the demobilization of the revolutionary forces that brought success to Madero's side.

With the settlement brokered by Madero with the Díaz regime, Orozco turned to business interests, involved in mining, retail commerce, and transport.[10]

Break with Madero

After Díaz's fall, Orozco became resentful at Madero's failure to name him to the cabinet or to a state governorship. Orozco was particularly upset with Madero's failure to implement a series of social reforms that he had promised at the beginning of the revolution. Orozco believed that Madero was very similar to Díaz, whom he had helped to overthrow. Orozco was then offered the governorship of Chihuahua,[11] which he refused, and Madero finally accepted his resignation from the federal government.

When Díaz presented his resignation, Orozco was named to a relatively junior position, commander of the federal rural police (Los Rurales) in Chihuahua. In June 1911, Orozco decided to run for governor of Chihuahua for the Club Independiente Chihuahuense, an organization opposed to Francisco I. Madero. After receiving many admonitions by the revolutionary hierarchy, Orozco was compelled to resign his candidacy on 15 July 1911. Subsequently, he refused a request to command the troops fighting Emiliano Zapata in the south.

On 3 March 1912, he announced his intention to revolt against the government of President Madero. Orozco financed his rebellion with his own assets and with confiscated livestock, which he sold in the neighboring U.S. state of Texas, and where he bought weapons and ammunition even after an embargo proclaimed by U.S. president William Taft in March 1912.

Revolt against Madero

On 3 March 1912 Orozco decreed a formal revolt against Madero's government. Orozco's forces, known as the Orozquistas and Colorados ("Red Flaggers"), defeated the Federal Army under General José González Salas. Seeing the potential danger that Orozco posed to his regime, Madero sent General Victoriano Huerta out of retirement to stop Orozco's rebellion. Huerta's troops defeated the orozquistas in Conejos, Rellano and Bachimba finally seizing Ciudad Juárez.[12]

After being wounded in Ojinaga, Orozco was forced to flee to the United States. After living for some months in Los Angeles, with his first cousin, Teodora Vázquez Molinar González (1879–1956) and husband, Carlos Díaz-Ferrales González (1878–1953) he was able to return to Chihuahua but extremely ill, affected with periodic rheumatism seizures.

After Huerta installed himself as President of Mexico in early 1913, Orozco agreed to support him if Huerta agreed to some reforms (such as payment of hacienda workers in hard money rather than company store scrip). Huerta agreed. Orozco led campaigns against the Constitutionalist Army that sought to oust Huerta in northern Mexico. Orozco's successes had brought promotionsCommanding General of all Mexican Federal forces, lead attacks against the revolutionaries, including Pancho Villa.{, and he rose to the rank of division general. Orozco defeated the Constitutionalist Army at Ciudad Camargo, Mapula, Santa Rosalía, Zacatecas, and Torreón. With his successes against that revolutionary force came their vitriol against him as a betrayer.[13]

After Huerta's fall Orozco announced his refusal to recognize the government of the new president, Francisco S. Carvajal whom he viewed to be similar to Madero. After briefly leading a revolt financed with his own money where he took in Guanajuato where he won several successive engagements against the Constitutionalists, he was forced to retreat because he lacked sufficient manpower to hold the ground he won. He was again forced into exile and was named "Supreme Military Commander."

Orozco y Huerta

After General Huerta's barracks (Ten Tragic Days), Orozco, upon learning of the murders of Madero and Pino Suárez, met with his representatives. As of March 7, 1913, the Orozquista troops were incorporated into the irregular militia.[14]

Government in exile

In efforts to overthrow Venustiano Carranza's government, Orozco and Huerta traveled throughout the United States, with the support of fellow exiles Gen. Marcelo Caraveo, Francisco Del Toro, Emilio Campa, and Gen. José Inez Salazar in Texas. Orozco traveled to San Antonio, St. Louis and New York. Eventually Enrique Creel and Huerta were able to strike a deal with the German government for the sale of $895,000.00 in weapons.

House arrest in the United States

In New York, Orozco and Huerta finalized plans to retake Mexico. En route to El Paso by train on 27 June 1915 the two were arrested in Newman, Texas, and charged with conspiracy to violate U.S. neutrality laws. He was placed under house arrest in his family's home at 1315 Wyoming Avenue El Paso, Texas, but managed to escape.

Orozco's Last Ride

Orozco successfully executed a planned escape to Sierra Blanca where he met up with leaders and future cabinet members (General José Delgado, Christoforo Caballero, Miguel Terrazas and Andreas Sandoval). The official U.S. report stated that Orozco and his men had crossed by Dick Love's ranch and had coerced the cook to prepare him a meal and attend his horses, while Orozco and his men got ready to steal Love's cattle. When the owner arrived, they fled on the rancher's horses. The facts of this are often disputed because in other accounts it is believed that the horses belonged to Orozco and Love set up Orozco to seek revenge for an earlier dispute. Love used his accusations to persuade 26 members from the 13th Cavalry Regiment, 8 local deputies and 13 Texas Rangers to pursue the mysterious horse thieves whom he purposefully fails to mention by name to ensure their participation. The posse in pursuit converged at Stephan's tank just west of High Lonesome in the Van Horn Mountains [15] Orozco, and his four men (Delgado, Caballero, Terrazas and Sandoval) were camped in a box canyon above Stephan's Tank where law enforcement caught and killed them. A Mexican version asserts that Orozco was murdered trying to resist the robbery of his own horses by Love and his men.[16] On 7 October a local hearing against the 40-plus Americans involved was initiated, but the court found the people involved innocent of all charges.

Personal life

Pascual Jr. married Refugio Frías and dedicated his youth to the transport of precious metals between the mining firms of the state. He was also the uncle of Maximiano Márquez Orozco, who participated in the Mexican Revolution as a colonel in the Villista Army. In the first years of the 20th century he was attracted by the ideas of the Flores Magón brothers and, in 1909 he started importing weaponry from the United States in the face of the imminent outbreak of the Mexican Revolution.

On 3 September 1915 Orozco's remains were placed in space 13 of the Masonic Holding Vault at Concordia Cemetery in El Paso, Texas, at the decision of his wife, dressed in a full Mexican general's uniform, with the Mexican flag draping his coffin, in front of three thousand followers and admirers. In 1925, his remains were returned to his home state of Chihuahua and interred in the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres (Rotunda of Illustrious Persons), Panteón de Dolores, in Chihuahua.[17]

In popular culture

- Orozco appears as a character in The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996), a novel by James Carlos Blake.

See also

References

- This article draws heavily on the corresponding article in the Spanish-language Wikipedia, which was accessed in the version of 6 March 2005.

- Meyer, Michael C. Mexican Rebel: Pascual Orozco and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1915. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1967

- Protestants and the Mexican Revolution: missionaries, ministers, and social change by Deborah J. Baldwin, p.76

- Mexican Rebel; Pascual Orozco and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1915, p. 15

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution, vol. 1, p. 176.

- Grieb, Kenneth J. "Pascual Orozco, Jr." in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p. 241. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution vol. 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986, p. 141, 176.

- Knight, The Mexican Revolution, vol. 1. p. 176.

- OROZCO, PASCUAL, JR. | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)

- Knight, The Mexican Revolution vol. 1, p. 229.

- Knight, The Mexican Revolution vol. 1, p. 305.

- Heribert von Feilitzsch, In Plain Sight: Felix A. Sommerfeld, Spymaster in Mexico, 1908 to 1914, Henselstone Verlag LLC., Amissville, VA, 2012, p. 165

- Grieb, "Pascual Orozco, Jr.", p. 241.

- Grieb, "Pascual Orozco, Jr.", p. 241.

- Alej, Norma Leticia Orozco /; Orozco, ro. "Pascual Orozco, héroe polémico". El Heraldo de Chihuahua. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHigh_Lonesome_from_Escondido.jpg

- Michael Meyer, Mexican Rebel 1967, p132

- Osorio Zúñiga, "Pascual Orozco Vázquez, Jr.", p. 1037.

Further reading

- Caballero, Raymond (2020). Pascual Orozco, ¿Héroe y traidor?. México, D.F.: Siglo XXI Editores.

- Caballero, Raymond (2017). Orozco, The Life and Death of a Mexican Revolutionary. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Caballero, Raymond (2015). Lynching Pascual Orozco, Mexican Revolutionary Hero and Paradox. Create Space. ISBN 978-1514382509.

- Meyer, Michael C. (1967). Mexican Rebel: Pascual Orozco and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1915. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- von Feilitzsch, Heribert (2012). Felix A. Sommerfeld: Spymaster in Mexico, 1908 to 1914. Amissville, Virginia: Henselstone Verlag. ISBN 9780985031701. OL 25414251M.