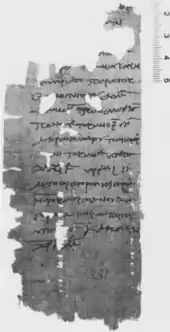

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 581

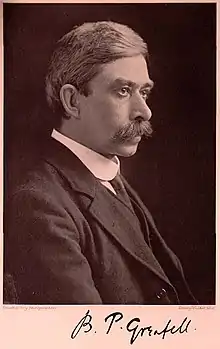

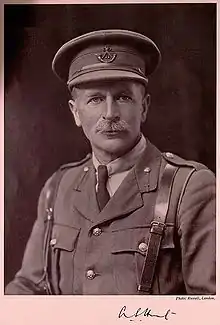

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 581 (P. Oxy. 581 or P. Oxy. III 581) is a papyrus fragment written in Ancient Greek, apparently recording the sale of a slave girl. Dating from 29 August 99 AD, P. Oxy. 581 was discovered, alongside hundreds of other papyri, by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt while excavating an ancient landfill at Oxyrhynchus in modern Egypt. The document's contents were published by the Egypt Exploration Fund in 1898, which also secured its donation to University College, Dundee, later the University of Dundee, in 1903 – where it still resides. Measuring 6.3 x 14.7 cm and consisting of 17 lines of text, the artifact represents the conclusion of a longer record, although the beginning of the papyrus was lost before it was found. P. Oxy. 581 has received a modest amount of scholarly attention, most recently and completely in a 2009 translation by classicist Amin Benaissa of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

The fragment probably documents the registration of a slaving sale with Oxyrhynchus' agoranomeion, a Roman civic institution involved with record-keeping and the supervision of taxation. P. Oxy. 581 mentions four individuals; the slave herself, likely an eight year-old female; the unnamed purchaser, for whom the transaction is being registered; Demas, brother of the purchaser as well as the slave's previous owner and Caecilius Clemens, an unspecified notary also connected to four other Oxyrhynchus Papyri dating from 86 AD–c.100 AD. An "inadvertent scribal omission",[1] whereby the stated value of 3,000 bronze drachmas, a largely obsolete currency, was not converted into its equivalent worth in silver, is regarded as an unusual mistake and has served to distinguish the record.

Background and description

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri are a collection of rare papyrus fragments discovered at an ancient landfill in Oxyrhynchus, modern-day Egypt.[2] The site was excavated from 1896 until 1907 by papyrologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt on behalf of the Graeco-Roman Branch of the Egypt Exploration Fund, which subsequently published the contents of the discoveries and donated them to supportive institutions around the world.[3][4] Aside from a minority of important biblical and classical literary fragments,[5] the vast majority of the collection is made up of correspondence relating to the private citizens of Oxyrhynchus during both the Ptolemaic Kingdom (305 BC–30 BC) and the successive Roman administration (32 BC–648 AD).[6][7]

P. Oxy. 581 was written in Ancient Greek, like most of the collection,[7] on 29 August 99 AD and was first published in Volume III of the Egypt Exploration Fund's 1898 catalogue.[8] Measuring 6.3 x 14 cm,[8][1] the "rather cramped"[9] document consists of 17 lines and is thought complete at the left, lower, and right sides but is fractured at the top;[9][8] the fragment is the conclusion of a longer message.[8] In 1903, according to a letter sent to then-Principal John Yule Mackay, the President and Committee of the Graeco-Roman Branch voted to present the papyrus to University College, Dundee,[4] which reorganised as the University of Dundee in 1967.[10] It is the only of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri to be part of the university's collection (reference number MS 142/1, previously MS 15/29), where it is preserved by resident archive services and mounted in glass.[11][12] As of 2006, P. Oxy. 581 is the oldest item in the institution's registry.[13] The document has featured in a short history by R. A. Coles of the Ashmolean Museum in 1998,[14] a fonds description by Dundee's Deputy Archivist Caroline Brown in June 2003[12] as well as a translation of Oxyrhynchus letters by classicist Amin Benaissa, a Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in 2009.[15] No known copies have yet been made of the original document.[12]

Transcription

[ ] . . |

...e |

Analysis

P. Oxy. 581 likely documents a registration for the sale of a slave with Oxyrhynchus' agoranomeion, or "notarial office".[1] Comprising ten magistrates known as agoranomi, these institutions were known in the Graeco-Roman world as arbitrating supervisors in a city's markets, residential areas and shipping ports.[16][17] However, in Egyptian settlements such as Oxyrhynchus, their primary focus was instead record-keeping and the preservation of private contracts.[17][7]

Consequently, according to Benaissa, all Oxyrhynchus Papyri implicating the agoranomeion can be categorised into three groups: "notifications of the cession or mortgage of catoecic land (I); orders to register the sale or mortgage of house and other immovable property or the sale of slaves (II); and orders to grant manumission to slaves ... (III)".[17] P. Oxy. 581 belongs to the second category and concerns the exchange of a young female slave, probably aged eight, between one Demas and his unnamed sibling.[9] Indeed, females comprised approximately two-thirds of the slave population in Roman Egypt overall, many raised as foundlings in citizen families and documented in contemporary censuses.[18]

The exact dating of the document, 29 August 99 AD, can be extracted from lines 12–16. The second year of Emperor Trajan's reign was 99 AD,[19] with August, named for inaugural Roman Emperor Augustus,[20] constituting the "month of Caesarius";[9] finally, the sixth Coptic intercalary day translates into the 29th of the month according to the Roman Julian calendar.[21]

Monetary significance

The artifact describing a slave-based transaction is confirmed by the price listing of "10 talents 3000 (drachmas) of bronze",[9] opined as a standard charge for Oxyrhynchus juveniles in commentaries by the academics J. David Thomas and William Linn Westermann, respectively citing P. Oxy. 2856 and P. Oxy. 48 as comparable examples.[22][23] Otherwise, P. Oxy. 581 is noted for an "accidental omission"[24] whereby the 3,000 bronze drachmas were not converted to display their equivalent value in silver, simply listing "talents".[9][24] Because bronze was an essentially obsolete currency in 99 AD, this has been considered a particularly unusual mistake.[24] Declaration of slave sales was an essential requirement for registration with the agoranomeion, which also supervised taxation on the transfer of assets.[25]

The notary in this case, one Caecilius Clemens, is similarly recorded in four other Oxyrhynchus Papyri as an unspecified official registering transactions within an approximate timeframe of 14 years (86 AD–c.100 AD); P. Oxy. 241 concerns the payment of a mortgage,[26] P. Oxy. 338 and P. Oxy. 340 both describe the sale of an abode[27][28] and P. Oxy. 4984 documents the submission of a loan agreement.[29]

References

Citations

- Benaissa 2009, p. 178

- Luijendijk 2010, p. 217

- Luijendijk 2010, pp. 225–26

- "Letter from the Secretary of the Egypt Exploration Fund". University of Dundee Archive Services. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Luijendijk 2010, pp. 243–44

- Luijendijk 2010, p. 241

- Luijendijk 2010, p. 225

- Grenfell & Hunt 1898b, p. 280

- Benaissa 2009, p. 179

- "History: 50th anniversary". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "Fragment of Oxyrhynchus Papyri". University of Dundee Archive Services. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "Fragment of Oxyrhynchus Papyri and related papers". Archives Hub. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Brown 2006, p. 169

- "Letter from Dr R. A. Coles, Papyrology Rooms, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford". University of Dundee Archive Services. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Benaissa 2009, pp. 178–79

- Aristotle 1921, p. 51

- Benaissa 2009, p. 157

- Huebner 2013, p. 59

- Hunt 2017, p. 79

- Hannah 2013, p. 98

- Hannah 2013, pp. 154–55

- Westermann 1955, p. 100

- Browne et al. 1971, p. 75

- Benaissa 2009, p. 172

- Benaissa 2009, p. 171

- Grenfell & Hunt 1898a, pp. 185–86

- Grenfell & Hunt 1898a, pp. 308–309

- Benaissa 2009, pp. 179–80

- Leith et al. 2009, p. 94

Bibliography

|

| |

- Aristotle (1921). "Atheniensium Respublica" [Frederic G. Kenyon]. In W. D. Ross (ed.). The Works of Aristotle. 10. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 605300427.

- Benaissa, Amin (2009). "Sixteen Letters to Agoranomi from Late First Century Oxyrhynchus". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH. 170: 157–185. ISSN 0084-5388.

- Brown, Caroline (2006). "Digitisation projects at the University of Dundee Archive Services". Program. Bingley, West Yorkshire: Emerald Group Publishing. 40 (2): 168–177. doi:10.1108/00330330610669280. ISSN 0033-0337.

- Browne, Gerald M.; Thomas, J. David; Turner, E. G.; Weinstein, Marcia E. (1971). Browne, Gerald M. (ed.). The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 38. London: Egypt Exploration Society. OCLC 43539416.

- Grenfell, Bernard Pyne; Hunt, Arthur Surridge (1898a). The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 2. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. OCLC 935406339.

- ——— ——— (1898b). The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 3. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. OCLC 502359250.

- Hannah, Robert (2013). Greek and Roman Calendars. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84-966751-7.

- Huebner, Sabine R. (2013). The Family in Roman Egypt: A Comparative Approach to Intergenerational Solidarity and Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10-724455-9.

- Hunt, Peter (2017). Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-40-518805-0.

- Leith, Dick; Parker, David C.; Pickering, S. R.; Benaissa, Amin; Colomo, Daniela; Cottier, Michel (2009). The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 74. London: Egypt Exploration Society. OCLC 690524232.

- Luijendijk, AnneMarie (2010). "Sacred Scriptures as Trash: Biblical Papyri from Oxyrhynchus". Vigiliae Christianae. Leiden: Brill Publishers. 64 (3): 217–254. doi:10.1163/157007210X498646. ISSN 0042-6032.

- Westermann, William Linn (1955). The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87-169040-1.