Panama Canal Railway

The Panama Canal Railway (Spanish: Ferrocarril de Panamá) is a railway line linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in Central America. The route stretches 47.6 miles (76.6 km) across the Isthmus of Panama from Colón (Atlantic) to Balboa (Pacific, near Panama City).[2] Because of the difficult physical conditions of the route and state of technology, the construction was renowned as an international engineering achievement, one that cost US$8 million and the lives of an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 workers. Opened in 1855, the railway preceded the Panama Canal by half a century; the ship canal was later constructed parallel to the railway.

| |

Current Panama Canal Railway line (interactive version)[1] | |

An intermodal train pulled by two Panama Canal F40PH locomotives through Colón, Panama. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Panama City, Panama |

| Locale | Isthmus of Panama |

| Dates of operation | January 28, 1855–Present |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Previous gauge | 5 ft (1,524 mm) |

| Length | 47.6 mi (76.6 km) |

| Other | |

| Website | panarail.com |

Panama Canal Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Known as the Panama Railroad Company when founded in the 19th century, today it is operated as Panama Canal Railway Company (reporting mark: PCRC). Since 1998 it has been jointly owned by Kansas City Southern and Mi-Jack Products and leased to the government of Panama.[3] The Panama Canal Railway currently provides both freight and passenger service.

The line was built by the United States and the principal incentive was the vast increase in passenger and freight traffic from eastern USA to California following the 1849 California Gold Rush. The United States Congress had provided subsidies to companies to operate mail and passenger steamships on the coasts, and supported some funds for construction of the railroad, which began in 1850; the first revenue train ran over the full length on January 28, 1855.[4] Referred to as an inter-oceanic railroad when it opened,[5] it was later also described by some as representing a "transcontinental" railroad, despite transversing only the narrow isthmus connecting the North and South American continents.[6][7][8][9] For a time the Panama Railroad also owned and operated ocean-going ships that provided mail and passenger service to a few major US East Coast and West Coast cities, respectively. The infrastructure of this railroad was of vital importance to the construction of the Panama Canal over a parallel route half a century later.

History of earlier isthmus crossings and plans

The Spanish improved what they called the Camino Real (royal road), and later the Las Cruces trail, built and maintained for transportation of cargo and passengers across the Isthmus of Panama. These were the main routes across the isthmus for more than three centuries. By the 19th century businessmen thought it was time to develop a cheaper, safer, and faster alternative. Railroad technology had developed in the early 19th century. Given the cost and difficulty of constructing a canal with the available technology, a railway seemed the ideal solution.

President Bolívar of La Gran Colombia (Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, Colombia) commissioned a study into the possibility of building a railway from Chagres (on the Chagres River) to the town of Panama City. This study was carried out between 1827 and 1829, just as railroads were being invented. The report stated that such a railway might be possible. However, the idea was shelved.

In 1836, United States President Andrew Jackson commissioned a study of proposed routes for inter-oceanic communication in order to protect the interests of Americans traveling between the oceans and those living in the developing Oregon Country of the Pacific Northwest. The United States acquired a franchise for a trans-Isthmian railroad; however, the scheme was disrupted by the economic downturn after the business panic of 1837, and came to nothing.

In 1838 a French company was given a concession for the construction of a road, rail, or canal route across the isthmus. An initial engineering study recommended a sea-level canal from Limón Bay to the bay of Boca del Monte, 12 miles (19 km) west of Panama. The proposed project collapsed for lack of technology and funding needed.

Following the United States' acquisition of Alta California in 1846 and the Oregon Territory in 1848, following the Mexican–American War and with the prospective movement of many more settlers to and from the West Coast, the United States again turned its attention to securing a safe, reliable, and speedy link between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In 1846 the United States signed a treaty with Colombia (then the Republic of New Granada) by which the United States guaranteed Colombian sovereignty over Panama and was authorized to build a railroad or canal at the Panamanian isthmus, guaranteeing its open transit.[10]

In 1847, a year before gold was discovered in California, Congress authorized subsidies to run two lines of mail and passenger steamships, one in the Atlantic and one in the Pacific. The Atlantic lines ran from New York City, Havana, Cuba, and New Orleans, Louisiana, to Panama's Chagres River on the Caribbean Sea, at a $300,000 subsidy. The proposed Pacific line ran with three steamships from Panama City, Panama to California and Oregon on the Pacific Coast, at a $200,000 subsidy. None of the steamships used in the Pacific was built before the mail contract was let.

In 1847, the east–west transit across the isthmus was by native dugout canoe (and later by modified lifeboats) up the often dangerous Chagres River. Travelers had to go overland by mules for the final 20 miles (32 km) over the old Spanish trails. The trails had fallen into serious disrepair after some 50 years of little or no maintenance; the 120 inches (3 m) of rain each year in the April–December rainy season also made the trails hard to maintain. A transit from the Atlantic to the Pacific or vice versa would usually take four to eight days by dugout canoe and mule. The transit was fraught with dangers, and travelers were subject to contracting tropical diseases along the way.

William H. Aspinwall, the man who had won the bid for the building and operating the Pacific mail steamships, conceived a plan to construct a railway across the isthmus. He and his partners created a company registered in New York, the Panama Railroad Company, raised $1,000,000 from the sale of stock, and hired companies to conduct engineering and route studies. Their venture happened to be well-timed, as the discovery of gold in California in January 1848 created a rush of emigrants wanting to cross the Isthmus of Panama to go to California.

The first steamship used on the Pacific run was the $200,000 three-mast, dual-paddle steamer SS California.[11][12] It was 203 feet (62 m) in length, 33.5 feet (10.2 m) in beam, and 20 feet (6.1 m) deep, with a draft of 14 feet (4.3 m), and grossed 1,057 tons. When it sailed around the Cape Horn of South America, it was the first steamship on the west coast of South and North America. When it stopped at Panama City on January 17, 1849, it was besieged by about 700 desperate gold seekers. Eventually, it departed Panama City for California on January 31, 1849, with almost 400 passengers, and entered San Francisco Bay, a distance of about 3,500 miles (5,600 km), on February 28, 1849 — 145 days after leaving New York. In San Francisco nearly all its crew except the captain deserted to seek their fortunes in the city and the gold fields. The ship was stranded for about four months until the company could buy a new supply of coal and hire a new — and much more expensive — crew.

The route between California and Panama was soon frequently traveled, as it provided one of the fastest links between San Francisco, California, and the East Coast cities, about 40 days' transit in total. Nearly all the gold that was shipped out of California went by the fast Panama route. Several new and larger paddle steamers were soon plying this new route.

1855 Panama Railroad

Construction

In January 1849, Aspinwall hired Colonel George W. Hughes to lead a survey party and pick a proposed Panama Railroad roadbed to Panama City. The eventual survey turned out to be full of errors, omissions, and optimistic forecasts, which made it of very little use. In April 1849, William Henry Aspinwall was chosen head of the Panama Railroad company, which was incorporated in the State of New York and initially raised $1,000,000 in capital.

In early 1850, George Law, owner of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, bought up the options of the land from the mouth of the Chagres River to the end of Navy Bay in order to force the directors of the new Panama Railroad to give him a position on the board of the company. Since there were no harbor facilities on the Atlantic side of the isthmus, they needed to create a town with docking facilities to unload their railroad supplies there. Refusing to allow Law onto the board, the directors decided to start building harbor facilities, an Atlantic terminus, and their railroad from the vacant site of Manzanillo Island. Starting in May 1850, what would become the city of Aspinwall (now Colón) was founded on 650 acres (260 ha) on the western end of Manzanillo Island, a treacherously marshy islet covered with mangrove trees.

The board solicited bids from construction companies in the United States to build the railroad. George Totten and John Trautwine initially submitted one of the winning bids. After surveying the railroad's proposed course and the probable construction difficulties and uncertainties, they withdrew their bid. Totten agreed to become the chief engineer on the railroad construction project, working for a salary instead of as a general contractor.

A new town on the Atlantic end of the railroad would have to be built on swampy ground that was often awash at high tide. The mangrove, palms, and poisonous manchineel (manzanilla) trees and other jungle vegetation had to be chopped down, and many of the buildings in the new town had to be built on stilts to keep them above the water. As more worker housing was needed, abandoned ships brought to the mouth of the Chagres River as part of the California Gold Rush were towed near the island and used for temporary housing. A steam-powered pile driver was brought from New York. Docks were constructed on pile-driven timbers, more and more of the island was stripped of vegetation, and elevated living spaces, docks, warehouses, and the like were constructed.

Before the railroad construction could get fully started, the island was connected to the Panamanian mainland by a causeway supported by pile-driven timbers. The first rolling stock consisting of a steam locomotive built by William Sellers & Co.,[13] and several gondola cars arrived in February 1851. The required steam locomotives, railroad cars, ties, rails, and other equipment were unloaded at the newly constructed docks and driven across the track laid across the about 200-yard (180 m) causeway separating the island from the mainland. This causeway connected the Atlantic terminus to the railroad and allowed the ties, iron rails, steam engines, workers, backfill, and other construction material to be hauled onto the mainland. Later, passengers and freight would go the same way. As the railroad progressed, more and more of the island was filled in, and the causeway was expanded to permanently connect the island to the mainland; its island status disappeared and the town of Aspinwall was created.[14]

In May 1850, the first preparations were begun on Manzanillo Island, and the start of the roadway was partially cleared of trees and jungle on the mainland. Very quickly, the difficulty of the scheme became apparent. The initial 8 miles (13 km) of the proposed route passed through a jungle of gelatinous swamps infested with alligators, the heat was stifling, mosquitoes and sandflies were everywhere, and deluges of up to 3 yards (2.7 m) of rain for almost half the year required some workers to work in swamp water up to four feet deep. When they tried to build a railroad near Aspinwall, the swamps were apparently endlessly deep, often requiring over 200 feet (60 m) of gravel backfill to secure a roadbed. Fortunately, they had found a quarry near Porto Bello, Panama, so they could load sandstone onto barges and tow it to Aspinwall to get the backfill needed to build the roadbed.

Built as the steam revolution was just starting, the only power equipment they had were a steam-driven pile driver, steam tugs, and steam locomotives equipped with gondola and dump cars for carrying fill material; the rest of the work had to be done by laborers wielding machete, axe, pick, shovel, black powder, and mule cart. As more track was laid, the workers had to continually add backfill to the roadbed, as it continued to slowly sink into the swamp. Once about 2 miles (3.2 km) of track were laid, the first solid ground was reached, at what was then called Monkey Hill (now Mount Hope). This was soon converted to a cemetery that accepted nearly continuous burials.

Cholera, yellow fever, and malaria took a deadly toll on workers. Despite the company's constant importation of high numbers of new workers, there were times when progress stalled for simple lack of semi-fit workers. All supplies and nearly all foodstuffs had to be imported from thousands of miles away, greatly adding to the cost of construction. Laborers came from the United States, the Caribbean Islands, and as far away as Ireland, India, China, and Australia.[15]

After almost 20 months of work, the Panama Railroad had laid about 8 miles (13 km) of track and had spent about $1,000,000 to cross the swamps to Gatún. The project's fortunes turned in November 1851 — just as they were running out of the original $1,000,000 — when two large paddle steamers, the SS Georgia and the SS Philadelphia, with about 1,000 passengers, were forced to shelter in Limón Bay, Panama, owing to a hurricane in the Caribbean. Since the railroad's docks had been completed by this time and rail had been laid 8 miles (13 km) up to Gatún on the Chagres River, it was possible to unload the ships' cargoes of emigrants and their luggage and transport them by rail, using flatcars and gondolas, for at least the first part of their journey up the Chagres River on their way to Panama City. Desperate to get off the ships and across the isthmus, the gold seekers paid $0.50 per mile and $3.00 per 100 pounds of luggage to be hauled to the end of the track. This infusion of money saved the company and made it possible to raise more capital to make it an ongoing moneymaker. The company's directors immediately ordered passenger cars, and the railway began passenger and freight operations with about 40 miles (64 km) of track still to be laid. Each year it added more and more track and charged more for its services. This greatly boosted the value of the company's franchise, enabling it to sell more stock to finance the remainder of the project, which took more than $8,000,000 and cost 5,000 to 10,000 workers' lives to complete.[16]

By July 1852, the company had finished 23 miles (37 km) of track and reached the Chagres River, where an enormous bridge had to be built. The first wooden bridge failed when the Chagres rose by over 40 feet (12 m) in a day and washed it away. Work was begun on a much higher, 300-foot-long (91 m), hefty iron bridge, which took more than a year to finish. In all, the company built more than 170 more bridges and culverts.

In January 1854, excavation began at the summit of the Continental Divide at the Culebra Cut, where the earth had to be cut from 20 feet (6 m) to 40 feet (12 m) deep over a distance of about 2,500 feet (760 m). Several months were spent digging. Later the Panama Canal required years to cut through this area deeply enough for a canal. The road over the crest of the continental divide at Culebra was finally completed from the Atlantic side in January 1855, 37 miles (60 km) of track having been laid from Aspinwall (Colón). A second team, working under less harsh conditions with railroad track, ties, railroad cars, steam locomotives, and other supplies brought around Cape Horn by ship, completed its 11 miles (18 km) of track from Panama City to the summit from the Pacific side of the isthmus at the same time.

On a rainy midnight on January 27, 1855, lit by sputtering whale oil lamps, the last rail was set in place on pine crossties. Chief engineer George Totten, in pouring rain with a nine-pound maul, drove the spike that completed the railroad. The next day the first locomotive with freight and passenger cars passed from sea to sea. The huge project was completed.[17]

Upon completion the railroad stretched 47 miles, 3,020 feet (76 km), with a maximum grade of 60 feet to the mile (11.4 m/km, or 1.14%). The summit grade, located 37.38 miles (60.16 km) from the Atlantic and 10.2 miles (16.4 km) from the Pacific, was 258.64 feet (78.83 m) above the assumed grade at the Atlantic terminus and 242.7 feet (74.0 m) above that at the Pacific, being 263.9 feet (80.4 m) above the mean tide of the Atlantic Ocean and the summit ridge 287 feet (87 m) above the same level.[18][19] The gauge was 5 ft (1,524 mm) in 53 lb/yd (26 kg/m), Ω-shaped rail. This gauge was that of the southern United States railway companies at the time. This gauge was converted to standard in the United States in May 1886 after the American Civil War, but remained in use in Panama until the railroad was rebuilt in 2001.[20]

They now had the job of making things permanent and upgrading the railway. Hastily erected wooden bridges that quickly rotted in the tropical heat and often torrential rain had to be replaced with iron bridges. Wooden trestles had to be converted to gravel embankments before they rotted away. The original pine railroad ties lasted only about a year, and had to be replaced with ties made of lignum vitae, a wood so hard that they had to drill the ties before driving in the screw spikes. The line was eventually built as double track.

The railroad became one of the most profitable in the world, charging up to $25 per passenger to travel over 47 miles (76 km) of hard-laid track. Upon completion, the railway was proclaimed an engineering marvel of the era. Until the opening of the Panama Canal, it carried the heaviest volume of freight per unit length of any railroad in the world. The existence of the railway was one of the keys to the selection of Panama as the site of the canal.

In 1881 the French Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique purchased controlling interest in the Panama Railway Company. In 1904, the United States government under Theodore Roosevelt purchased the railway from the French canal company. At the time, railway assets included some 75 miles (121 km) of track, 35 locomotives, 30 passenger cars, and 900 freight cars. Much of this equipment was worn out or obsolete and had to be scrapped.

Financing

The railway cost some US$8 million to build — eight times the initial 1850 estimate — and presented considerable engineering challenges, passing over mountains and through swamps. Over 300 bridges and culverts needed to be built along the route.

It was built and financed by private companies from the United States. Among the key individuals in building the railway were William H. Aspinwall, David Hoadley, George Muirson Totten, and John Lloyd Stephens. The railroad was built and originally owned by a publicly traded corporation based in New York City, the Panama Rail Road Company, which was chartered by the State of New York on April 7, 1849, and the stock in which would eventually become some of the most highly valued of the era. The company bought exclusive rights from the government of Colombia (then known as Republic of New Granada, of which Panama was a part) to build the railroad across the isthmus.

The railway carried significant traffic even while it was under construction, with traffic carried by canoe and mules over the unfinished sections. This had not been originally intended, but people crossing the isthmus to California and returning east were eager to use such track as had been laid. When only 7 miles (11 km) of track had been completed, the railway was doing a brisk business, charging $0.50 per mile per person for the train ride and increasing to $25 per person when the line was finally completed. By the time the line was officially completed and the first revenue train ran over the full length of its grade on January 28, 1855, more than one-third of its $8 million cost had already been paid for from fares and freight tariffs.

The fare for first-class passage was set at $25 one way, one of the highest rates in existence for a 47 miles (76 km) ride.[21] High prices for carrying freight and passengers, despite very expensive ongoing maintenance and upgrades, made the railroad one of the most profitable in the world. Engineering and medical difficulties made the Panama Railway the most expensive railway, per unit length of track, built at the time.

Death toll

It is estimated that from 5,000 to 10,000 people may have died in the construction of the railroad, though the Panama Railway company kept no official count and the total may be higher or lower. Cholera, malaria, and yellow fever killed thousands of workers, who were from the United States, Europe, Colombia, China, and the Caribbean islands, and also included some African slaves. Many of these workers had come to Panama to seek their fortune and had arrived with little or no identification. Many died with no known next of kin, nor permanent address, nor even a known surname.

Cadaver trade

Disease and exhaustion took a heavy toll on workers. The connection between mosquitoes and malaria, and ways of preventing the disease, were not understood. The company sold workers' corpses to medical schools abroad, using the income to maintain the company hospital.

Shipping lines

The Panama Railway also operated a significant shipping line, connecting its service with New York and San Francisco. It ran a Central American line of steamships linking Nicaragua, Costa Rica, San Salvador, and Guatemala to Panama City.[22] The shipping service was greatly expanded when canal construction began. Ships included the SS Salvador, SS Guatemala, SS Cristobal, and SS Ancon, which became the first of the ships to cross the completed canal in 1914.

Map of the Panama Railroad, 1861

Map of the Panama Railroad, 1861 International connections to the Panama Railroad, 1861

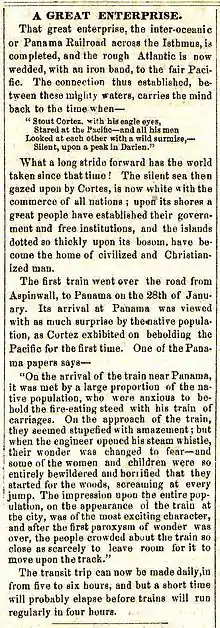

International connections to the Panama Railroad, 1861 Panama Railroad opens; freight tariffs, 1855 [transcription available]

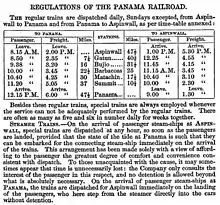

Panama Railroad opens; freight tariffs, 1855 [transcription available] Panama Railroad Regulations & Schedule, 1861 [transcription available]

Panama Railroad Regulations & Schedule, 1861 [transcription available]

1904–12 rebuild: Panama Canal building and afterward

In 1904 the United States took over the license to build and operate the canal. The choice to use locks and an artificial lake (Gatun) meant that the old railway route from 1855 had to be changed because it followed the Chagres River valley, which would be flooded by the lake. Also, the railway would be extended and altered continuously for the building process. The stock of the Panama Railway Company, vital in canal construction, was entirely controlled by the United States Secretary of War.[23]

Canal construction years

The construction of the Panama Canal was envisioned by John Frank Stevens, chief American railroad construction engineer, as a huge earthmoving project using the extended railroad system. Many tracks were added temporally to transport the sand and rock from the excavation. Stevens used the biggest and most durable equipment available. The French equipment was nearly all judged obsolete, worn out, or too light duty, and nearly all their railroad equipment was not built for heavy-duty use. Some of this French equipment was melted down and converted into medals presented to men working on the Panama Canal.

Also, since the 1855 route followed the Chagres valley (which would become Gatun Lake), the route had to change. The new railroad, starting in 1904, had to be greatly upgraded with heavy-duty double-tracked rails over most of the line to accommodate all the new rolling stock of about 115 powerful locomotives, 2,300 dirt spoils railroad cars, and 102 railroad-mounted steam shovels brought in from the United States and elsewhere. The steam shovels were some of the largest in the world when they were introduced. The new permanent railroad closely paralleled the canal where it could and was moved and reconstructed where it interfered with the canal work. In addition to moving and expanding the railroad where needed, considerable track additions and extensive machine shops and maintenance facilities were added, and other upgrades were made to the rail system. These improvements were started at about the same time the extensive mosquito abatement projects were undertaken to make it safer to work in Panama. When the mosquitoes were under control, much of the railroad was ready to go to work.

The railway greatly assisted the building of the Panama Canal. Besides hauling millions of tons of men, equipment, and supplies, the railroad did much more. Essentially all of the hundreds of millions of cubic yards of material removed from the required canal cuts were broken up by explosives, loaded by steam shovels, mounted on one set of railroad tracks, loaded onto rail cars, and hauled out by locomotives pulling the spoils cars running on parallel tracks.

Most of the cars carrying the dirt spoils were wooden flat cars lined with steel floors that used a crude but effective unloading device, the Lidgerwood system. The railroad cars had only one side, and steel aprons bridged the spaces between them. The rock and dirt were first blasted loose by explosives. Two sets of tracks were then built or moved up to where the loosened material lay. The steam shovels, moving on one set of tracks, picked up the loosened dirt and piled it on the flat cars traveling on a parallel set of tracks. The dirt was piled high up against the one closed side of the car. The train moved forward until all cars were filled. A typical train had 20 dirt cars arranged as essentially one long car.

On arrival of the train at one of the approximately 60 different dumping grounds, a three-ton steel plow was put on the last car (or a car carrying the plow was attached as the last car) and a huge winch with a braided steel cable stretching the length of all cars was attached to the engine. The winch, powered by the train's steam engine, pulled the plow the length of the dirt loaded train by winching up the steel cable. The plow scraped the dirt off the railroad cars, allowing the entire trainload of dirt cars to be unloaded in ten minutes or less. The plow and winch were then detached for use on another train. Another plow, mounted on a steam engine, then plowed the dirt spoils away from the track.[24]

When the fill got large enough, the track was relocated on top of the old fill to allow almost continuous unloading of new fill with minimal effort. When the steam shovels or dirt trains needed to move to a new section, techniques were developed by William Bierd, former head of the Panama Railroad, to pick up large sections of track and their attached ties by steam-powered cranes and relocate them intact, without disassembling and rebuilding the track. A dozen men could move a mile of track a day — the work previously done by up to 600 men. This allowed the tracks used by both the steam shovels and dirt trains to be quickly moved to wherever they needed to go. While constructing the Culebra Cut (Gaillard Cut), about 160 loaded dirt trains went out daily and returned empty.

Locomotive spreading material on the Corozal dump

Locomotive spreading material on the Corozal dump Track laying follows excavation

Track laying follows excavation New dump car

New dump car Shifting track by hand

Shifting track by hand Tracks on breakwater

Tracks on breakwater

The railroads, steam shovels, steam-powered cranes, rock crushers, cement mixers, dredges, and pneumatic power drills used to drill holes for explosives (about 30,000,000 pounds (14,000 t) were used) were some of the new construction equipment used to construct the canal. Nearly all this equipment was built by new, extensive machine-building technology developed and made in the United States by companies such as the Joshua Hendy Iron Works. In addition the canal used large refrigeration systems for making ice, large electrical motors to power the pumps and controls on the canal's locks, and other new technology. They built extensive electrical generation and distribution systems, one of the first large-scale uses of large electrical motors. Electricity-powered donkey engines pulled the ships through the locks on railroad tracks laid parallel to the locks.

Permanent railroad

.jpg.webp)

New technology not available in the 1850s allowed enormous earth cuts and fills to be used on the new railroad that were many times larger than those done in the original 1851–55 construction. The rebuilt, much improved, and often rerouted Panama Railway continued alongside the new canal and across Gatun Lake. The railroad was completed in its final configuration in 1912, two years before the canal, at a cost of $9 million—$1 million more than the original.

After World War II, few additional improvements were made to the Panama Railway. Its condition declined after 1979, when the US government handed over control to the government of Panama.

Except for dedicated railroad sections, such as the concrete factory, the broad 5 ft (1,524 mm) gauge was used. This gauge was also used for the locomotives along the locks ("mules"). When the gauge for the railroad was changed in 2001, the mules kept the broad gauge.

2001 reconstruction

In 2001, the railroad was reopened after a large project to upgrade the railway. On June 19, 1998, the government of Panama had turned over control to the private Panama Canal Railway Company (PCRC), a joint venture between the Kansas City Southern Railroad and privately held Lanigan Holdings, LLC. The rebuild project carried shipping containers as a complement to the Panama Canal in cargo transport. Two container handling terminals were created: on the Atlantic side, near Manzanillo International Terminal (Colón), and the Pacific Intermodal Terminal near Balboa Harbour. There are passenger stations in Colón (called Atlantic Passenger Station) and Corozal railway station, 4 mi (6 km) from Panama City. No other stations exist.

Tracks

The renovation project involved the laying of new ballast, sleepers (ties), and rail. The track gauge was changed from 5 ft (1,524 mm) to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge, which is the same "standard gauge" used on the North American rail network. The rails were replaced with 136 lb/yd (67.46 kg/m) continuously welded rail, purchased from Sydney Steel Corporation in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada. Similarly, the crushed rock used for ballast was purchased from Martin Marietta Materials in Auld's Cove, Nova Scotia, Canada. Concrete sleepers (ties) were used to avoid termite and other insect damage. The route was realigned slightly, with a shortcut added around the Gatún locks. The line is now single track, with some strategically placed sections of double track (near Gamboa and Monte Lirio). The floor of the old Miraflores Tunnel had to be lowered to accommodate the extra height of double-stacked containers. A maintenance shop was built near Colón that can also receive the container-loading portal cranes, which are also owned and operated by PCRC.

Passenger service and freight capacity

As of 2018, one passenger service per direction is offered every Monday to Friday. The Corozal (Panama City)–Colón train leaves at 7:15 a.m., and the return train leaves at 5:15 p.m., with a traveling time of one hour.[25]

While the main purpose of the train is as a commuter rail for those living in Panama City and working in Colon, it has also become a popular tourist excursion. It travels the historic route across the country between coastal cities and passes through the lush jungle and along Lake Gatun, which makes up a substantial section of the canal network. As it was used during the construction of the canal, it runs parallel and offers views of the canal. The rail cars are classic in nature, with first-class amenities, bar service, and second-level viewing areas and outdoor viewing. It offers a variety of ticket options, from monthly reserved seats to one-way purchases.[26]

For freight services — that is, transporting containers across the isthmus — the initial capacity allows for 10 trains to run in each direction per 24 hours. With the current rail configuration, this could be extended to a maximum of 32 trains per 24 hours. A train is composed of double-stack bulkhead-type rail cars, typically containing 75 containers, a mix of 60 × 40' and 15 × 20' containers. The basic capacity is around 500,000 container moves a year (approximately 900,000 TEU), with a maximum capacity of 2 million TEU per year.[27]

Freight trains are loaded and unloaded in the railway terminals by portal cranes, serving 3,000 ft (910 m) long tracks that can be expanded into six tracks. Containers are transported to and from nearby dock container stacks by truck on a dedicated road.

As of 2013, the railroad was handling about 1,500 containers per day. The Panama Canal carries some 33,500 containers each day.[28]

2020 Chagres River bridge damage

On June 23, 2020 the bulk carrier (freighter) "Bluebill" struck the railway bridge crossing the Chagres River,[29] near Gamboa, severely damaging the bridge and severing the rail route approximately midway between the two terminals.

Rolling stock

Original railroad

Many of the early locomotives were built by the Portland Company.[30] All were five-foot gauge.

| Name | Type | Portland shop number | Date | Cylinders | Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nueva Granada | 0-4-0 Tank | 37 | 10/1852 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Bogotá | 0-4-0 Tank | 38 | 11/1852 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Panama | 0-4-0 Tank | 39 | 11/1852 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Gorgona | 0-4-0 | 65 | 4/1854 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Obispo | 0-4-0 | 69 | 9/1854 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Matachin | 0-4-0 | 70 | 8/1854 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Gatun | 0-4-0 | 78 | 8/1855 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Manzanilla | 0-4-0 | 79 | 8/1855 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Cardenas | 4-4-0 | 89 | 8/1856 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Barbacoas | 4-4-0 | 90 | 8/1856 | 13″×20″ | 54″ |

| Atlantic | 4-4-0 | 125 | 4/1865 | 13″×20″ | 54.75″ |

| Pacific | 4-4-0 | 126 | 5/1865 | 13″×20″ | 54.75″ |

| Colon | 0-4-0 Tank | 136 | 8/1865 | 12″×18″ | 42.5″ |

| Chiriqui | 0-4-0 | 148 | 9/1867 | 12″×18″ | 40″ |

| Darien | 0-4-0 | 149 | 11/1867 | 12″×18″ | 40″ |

| South America | 4-4-0 | 150 | 11/1867 | 13″×20″ | 55.25″ |

| North America | 4-4-0 | 151 | 2/1868 | 13″×20″ | 55.25″ |

| New York | 4-4-0 | 157 | 4/1869 | 13″×20″ | 55.25″ |

| San Francisco | 4-4-0 | 158 | 4/1869 | 13″×20″ | 55.25″ |

| Verugas | 0-4-0 | 261 | 5/1873 | 12″×18″ | 43″ |

2001 rebuild

In the 2001 rebuild, most rolling stock was replaced, too, as the line was switched to standard gauge. The railroad has a fleet of several historic passenger cars in service, including PCRC #102, which is a vintage dome car first built by the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1955.[31] The passenger cars are Clocker coaches built by the Budd Company and leased from Amtrak.[32]

As of August 2009, the railway's motive power consists of ten former Amtrak F40PHs, five EMD SD60s and two EMD SD40-2s from the Kansas City Southern Railroad, and one GP10. The locomotive numbering scheme begins with 1855, honoring the year in which the original Panama Railroad was completed.

| Model | Quantity | Acquired | Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMD GP10 | 1 | 2001 | 1855 |

| EMD F40PH | 10 | 2001 | 1856–65 |

| EMD SD40-2 | 2 | 2008 | 1866–67 |

| EMD SD60 | 5 | 2008 | 1868–72 |

The rebuilt railway's revenue freight rolling stock consists of 5-well, articulated, double-stack container railcars with bulkheads. The 265-foot-long car sets were built by Gunderson Inc. and each car set can hold ten 40 foot containers.[33] The bottom level in each well can hold two 20 foot containers instead of one 40 foot unit.[34] The intermodal terminals at each end can accommodate trains of 11 of these cars, which carry a total of up to 110 forty-foot equivalent units (FEUs).

Gallery

A Panama Canal Railway passenger train parked along the platform of Colon station.

A Panama Canal Railway passenger train parked along the platform of Colon station. An early morning passenger train at the Panama City railroad station.

An early morning passenger train at the Panama City railroad station..jpg.webp) PCRC passenger car

PCRC passenger car Interior of passenger car

Interior of passenger car Dome car interior

Dome car interior PCRC container train using well cars

PCRC container train using well cars.jpg.webp) Bridge over Chagres River in Gamboa

Bridge over Chagres River in Gamboa

See also

References

- "The Panama Rail Road". panamarailroad.org. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Barrett, John (1913). "Panama Canal". HathiTrust. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- "kcsi.com". www.kcsi.com.

- Grigore, Julius. "The Influence of the United States Navy Upon the Panama Railroad." (1994).

- "A Great Enterprise", The Portland (Maine) Transcript [Newspaper], February 17, 1855

- The Panama Rail Road, retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "The Panama Railroad" (Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum), retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Engines of our Ingenuity", Episode No.1208: THE PANAMA RAILROAD], retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Britannica, The New Panama Railroad: World’s Ninth Wonder, 2007-04-17.

- David McCullough. Brave Companions: Portraits in History. Simon & Schuster, 1992. p. 93. ISBN 0-671-79276-8.

- Steamship California, accessed 27 August 2009 Archived 14 September 2002 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- "APL: History – California". 21 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012.

- "American Machinist". 1914.

- Schott, Joseph L.; Rails Across Panama; Bobbs Merril Co. 1967; pp.19-26; ASIN: B0027ISM8A

- Fessenden Nott Otis, Isthmus of Panama: History of the Panama Railroad; and of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1867, pp. 21-36

- "The Panama Railroad - Part 1".

- "Harper's New Monthly Magazine". March 1855.

- Otis, Fessenden Nott; Illustrated History of the Panama Railroad Harper & Brothers, New York, 1861

- "Map of old Panama Railroad". Panama Railroad.

- Tom Daspit. "The Days They Changed the Gauge". Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- Snow, Franklin (1927). "The Railways and the Panama Canal". The North American Review (834 ed.). 224: 29–40.

- Fessenden Nott Otis, Isthmus of Panama: History of the Panama railroad; and of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1867 pp 148-222.

- Hurley, Edward N. (1927). The Bridge to France. Philadelphia & London: J. B. Lippincott Company. LCCN 27011802. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- DuTemple, Lesley A. "The Panama Canal"; 2002; pp50-55; Lerner Publishing Group; ISBN 978-0822500797

- "Schedules and rates". PCRC. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Asta, Jean. "Rail Travel in Panama". USA Today. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- "Capacity". Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- Panama Canal rail traffic hit by computer glitch, Reuters, 22 March 2013.

- "Bulker Damages Railroad Bridge in the Panama Canal". The Maritime Executive. 2020-06-24. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- Dole, Richard F. (1978). "Portland Company Construction list". Railroad History. The Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. 139 (Autumn 1978): 24–31.

- SP TRAINLINE Fall 2018

- "Panama Canal Railway's passenger train". TrainsMag.com.

- "ATSF Double Stack Cars - DTTX #63179". www.qstation.org.

- "134. Panama Canal Railway".

Literature

- Why the Panama Route Was Originally Chosen. By Crisanto Medina, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary from Guatemala to France. Publisher: The North American Review, Vol. 177, (September 1, 1903)

- The story of Panama: the new route to India. By Frank A. Gause and Charles Carl Carr. Publishers: Silver, Burdett and Company 1912

- F. N. Otis: Isthmus of Panama: history of the Panama railroad; and of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Together with a travellers' guide and business man's hand-book for the Panama Railroad and the lines of steamships connecting it with Europe, the United States, the north and south Atlantic and Pacific coasts, China, Australia, and Japan Publisher: Harper & Brothers New York, 1867 - Internet Archive

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panama Railroad. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panama Canal Railway. |

- Panama Canal Railway Company – official site

- The Panama Railroad – an unofficial page on the Panama Railroad

- Panama Railroad: Stock Certificates – an 1855 newspaper report of its opening, 1861 & 1913 maps, early Harper's engravings, and 1861 schedule.

- 1860s North American Steamship Co. – Panama Railroad ticket from San Francisco to New York.

- "Gun Train Guards Ends of Panama Canal -- Rolling Fort Crosses Isthmus in Two Hours" Popular Mechanics, December 1934 pp.844-845 - article includes drawings

- Construction engines and rolling-stock recovered from the bottom of Gatun lake