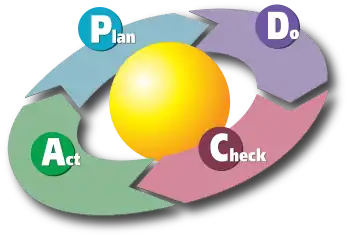

PDCA

PDCA (plan–do–check–act or plan–do–check–adjust) is an iterative four-step management method used in business for the control and continuous improvement of processes and products.[1] It is also known as the Deming circle/cycle/wheel, the Shewhart cycle, the control circle/cycle, or plan–do–study–act (PDSA). Another version of this PDCA cycle is OPDCA.[2] The added "O" stands for observation or as some versions say: "Observe the current condition." This emphasis on observation and current condition has currency with the literature on lean manufacturing and the Toyota Production System.[3] The PDCA cycle, with Ishikawa’s changes, can be traced back to S. Mizuno of the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1959.[4]

Meaning

Plan

Establish objectives and processes required to deliver the desired results.

Do

Carry out the objectives from the previous step.

Check

During the check phase, the data and results gathered from the do phase are evaluated. Data is compared to the expected outcomes to see any similarities and differences. The testing process is also evaluated to see if there were any changes from the original test created during the planning phase. If the data is placed in a chart it can make it easier to see any trends if the PDCA cycle is conducted multiple times. This helps to see what changes work better than others, and if said changes can be improved as well.

Example: Gap analysis, or Appraisals.

Act

Also called "Adjust", this act phase is where a process is improved. Records from the "do" and "check" phases help identify issues with the process. These issues may include problems, non-conformities, opportunities for improvement, inefficiencies and other issues that result in outcomes that are evidently less-than-optimal. Root causes of such issues are investigated, found and eliminated by modifying the process. Risk is re-evaluated. At the end of the actions in this phase, the process has better instructions, standards or goals. Planning for the next cycle can proceed with a better base-line. Work in the next do phase should not create recurrence of the identified issues; if it does, then the action was not effective.

About

PDCA was made popular by W. Edwards Deming, who is considered by many to be the father of modern quality control; however, he always referred to it as the "Shewhart cycle". Later in Deming's career, he modified PDCA to "Plan, Do, Study, Act" (PDSA) because he felt that "check" emphasized inspection over analysis.[6] The PDSA cycle was used to create the model of know-how transfer process,[7] and other models.[8]

The concept of PDCA is based on the scientific method, as developed from the work of Francis Bacon (Novum Organum, 1620). The scientific method can be written as "hypothesis–experiment–evaluation" or as "plan–do–check". Walter A. Shewhart described manufacture under "control"—under statistical control—as a three-step process of specification, production, and inspection.[9]:45 He also specifically related this to the scientific method of hypothesis, experiment, and evaluation. Shewhart says that the statistician "must help to change the demand [for goods] by showing [...] how to close up the tolerance range and to improve the quality of goods."[9]:48 Clearly, Shewhart intended the analyst to take action based on the conclusions of the evaluation. According to Deming, during his lectures in Japan in the early 1920s, the Japanese participants shortened the steps to the now traditional plan, do, check, act.[4] Deming preferred plan, do, study, act because "study" has connotations in English closer to Shewhart's intent than "check".[10]

A fundamental principle of the scientific method and PDCA is iteration—once a hypothesis is confirmed (or negated), executing the cycle again will extend the knowledge further. Repeating the PDCA cycle can bring its users closer to the goal, usually a perfect operation and output.[10]

PDCA (and other forms of scientific problem solving) is also known as a system for developing critical thinking. At Toyota this is also known as "Building people before building cars".[11] Toyota and other lean manufacturing companies propose that an engaged, problem-solving workforce using PDCA in a culture of critical thinking is better able to innovate and stay ahead of the competition through rigorous problem solving and the subsequent innovations.[11]

Deming continually emphasized iterating towards an improved system, hence PDCA should be repeatedly implemented in spirals of increasing knowledge of the system that converge on the ultimate goal, each cycle closer than the previous. One can envision an open coil spring, with each loop being one cycle of the scientific method, and each complete cycle indicating an increase in our knowledge of the system under study. This approach is based on the belief that our knowledge and skills are limited, but improving. Especially at the start of a project, key information may not be known; the PDCA—scientific method—provides feedback to justify guesses (hypotheses) and increase knowledge. Rather than enter "analysis paralysis" to get it perfect the first time, it is better to be approximately right than exactly wrong. With improved knowledge, one may choose to refine or alter the goal (ideal state). The aim of the PDCA cycle is to bring its users closer to whatever goal they choose.[3]:160

When PDCA is used for complex projects or products with a certain controversy, checking with external stakeholders should happen before the Do stage, since changes to projects and products that are already in detailed design can be costly; this is also seen as Plan-Check-Do-Act.

Rate of change, that is, rate of improvement, is a key competitive factor in today's world. PDCA allows for major "jumps" in performance ("breakthroughs" often desired in a Western approach), as well as kaizen (frequent small improvements). In the United States a PDCA approach is usually associated with a sizable project involving numerous people's time, and thus managers want to see large "breakthrough" improvements to justify the effort expended. However, the scientific method and PDCA apply to all sorts of projects and improvement activities.[3]:76

See also

References

- Tague, Nancy R. (2005) [1995]. "Plan–Do–Study–Act cycle". The quality toolbox (2nd ed.). Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press. pp. 390–392. ISBN 978-0873896399. OCLC 57251077.

- Foresight University, The Foresight Guide, Shewhart's Learning and Deming's Quality Cycle,

- Rother, Mike (2010). Toyota kata: managing people for improvement, adaptiveness, and superior results. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071635233. OCLC 318409119.

- Deming, W. Edwards (1986). Out of the crisis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study. p. 88. ISBN 978-0911379013. OCLC 13126265.

- "Taking the first step with PDCA". 2 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Aguayo, Rafael (1990). Dr. Deming: the American who taught the Japanese about quality. A Lyle Stuart book. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Pub. Group. p. 76. ISBN 978-0818405198. OCLC 22347078. Also published by Simon & Schuster, 1991.

- Dubickis, Mikus; Gaile-Sarkane, Elīna (December 2017). "Transfer of know-how based on learning outcomes for development of open innovation". Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 3 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s40852-017-0053-4.

- Dubberly, Hugh (2008) [2004]. "How do you design?: a compendium of models". dubberly.com. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- Shewhart, Walter Andrew (1986) [1939]. Statistical method from the viewpoint of quality control. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0486652320. OCLC 13822053. Reprint. Originally published: Washington, DC: Graduate School of the Department of Agriculture, 1939.

- Moen, Ronald; Norman, Clifford. "Evolution of the PDCA cycle" (PDF). westga.edu. Paper delivered to the Asian Network for Quality Conference in Tokyo on September 17, 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- Liker, Jeffrey K. (2004). The Toyota way: 14 management principles from the world's greatest manufacturer. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071392310. OCLC 54005437.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to PDCA. |

- Kolesar, Peter J. (2005) [1994]. "What Deming told the Japanese in 1950". In Wood, John C.; Wood, Michael C. (eds.). W. Edwards Deming: critical evaluations in business and management. 2. New York: Routledge. pp. 87–107. ISBN 9780415323888. OCLC 55738077. Reprint. Originally published: Quality Management Journal 2(1) (1994): 9–24.

- Langley, Gerald J.; Moen, Ronald D.; Nolan, Kevin M.; Nolan, Thomas W.; Norman, Clifford L.; Provost, Lloyd P. (2009) [1996]. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 9780470192412. OCLC 236325893.

- Shewhart, Walter Andrew (1980) [1931]. Economic control of quality of manufactured product. Milwaukee: American Society for Quality. ISBN 978-0873890762. OCLC 7543940. 50th anniversary commemorative reissue. Originally published: New York: Van Nostrand, 1931.