Operation Outside the Box

Operation Outside the Box[3][4][5][6] (Hebrew: מבצע מחוץ לקופסה,[7] Mivtza Michutz La'Kufsa) was an Israeli airstrike on a suspected nuclear reactor,[8] referred to as the Al Kibar site (also referred to in IAEA documents as Dair Alzour), in the Deir ez-Zor region of Syria,[9] which occurred just after midnight (local time) on 6 September 2007. The Israeli and U.S. governments did not announce the secret raids for seven months.[10] The White House and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) subsequently confirmed that American intelligence had also indicated the site was a nuclear facility with a military purpose, though Syria denies this.[11][12] A 2009 International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) investigation reported evidence of uranium and graphite and concluded that the site bore features resembling an undeclared nuclear reactor. IAEA was initially unable to confirm or deny the nature of the site because, according to IAEA, Syria failed to provide necessary cooperation with the IAEA investigation.[13][14] Syria has disputed these claims.[15] Nearly four years later, in April 2011 during the Syrian Civil War, the IAEA officially confirmed that the site was a nuclear reactor.[8] Israel did not acknowledge the attack until 2018.[16]

| Orchard/Bustan | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Iran–Israel proxy conflict | |

Before and after photo of target released by the U.S. government | |

| Operational scope | Strategic bombing run |

| Planned by | Israeli Air Force[1] |

| Objective | Destroy the Syrian nuclear site, located in the Deir ez-Zor region |

| Date | 6 September 2007 |

| Executed by | F-15I Ra'am fighters F-16I Sufa fighters 1 ELINT aircraft 1 helicopter Shaldag special forces |

| Outcome | Successful destruction of the site |

| Casualties | 10 North Korean nuclear scientists allegedly killed.[2] |

The attack reportedly followed Israeli top-level consultations with the Bush Administration.[17] After realizing that the US was not willing to bomb the site after being told so by U.S. President George W. Bush, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert decided to adhere to the 1981 Begin Doctrine and unilaterally strike to prevent a Syrian nuclear weapons capability, despite serious concerns about Syrian retaliation. In stark contrast to the doctrine's prior usage against Iraq, the airstrike against Syria did not elicit international outcry. A main reason is that Israel maintained total and complete silence regarding the attack, and Syria covered up its activities at the site and did not cooperate fully with the IAEA. The international silence may have been a tacit recognition of the inevitability of preemptive attacks on "clandestine nuclear programs in their early stages." If true, the Begin Doctrine has undoubtedly played a role in shaping this global perception.[18]

According to official government confirmation on 21 March 2018, the raid was carried out by Israeli Air Force (IAF) 69 Squadron F-15Is,[19] and 119 Squadron and 253 Squadron F-16Is,[20] and an ELINT aircraft; as many as eight aircraft participated and at least four of these crossed into Syrian airspace.[21] The fighters were equipped with AGM-65 Maverick missiles, 500 lb bombs, and external fuel tanks.[5][22] One report stated that a team of elite Israeli Shaldag special-forces commandos arrived at the site the day before so that they could highlight the target with laser designators,[19] while a later report identified Sayeret Matkal special-forces commandos as involved.[23]

The attack pioneered the use of Israel's electronic warfare capabilities,[24] as IAF electronic warfare (EW) systems took over Syria's air defense systems, feeding them a false sky-picture[24] for the entire period of time that the Israeli fighter jets needed to cross Syria, bomb their target and return.[25]

On 6 March 2017, the Kibar nuclear site was captured by the Syrian Democratic Forces – a U.S.-backed coalition of Kurdish and Arab militia fighters – from a retreating ISIL force in northern Deir Ezzor province.

Pre-strike activity

In 2001, the Mossad, Israel's external intelligence service, was profiling newly inducted Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Visits by North Korean dignitaries, which focused on advanced arms deliveries, were noticed. Aman, Israel's military intelligence department, suggested nuclear arms were being discussed, but the Mossad dismissed this theory. In spring 2004, U.S. intelligence reported multiple communications between Syria and North Korea, and traced the calls to a desert location called al-Kibar. Unit 8200, Israel's signals intelligence and codebreaking unit, added the location to its watch list.[26]

The Daily Telegraph, citing anonymous sources, reported that in December 2006, a top Syrian official (according to one article this was the head of the Atomic Energy Commission of Syria, Ibrahim Othman[27]) arrived in London under a false name. The Mossad had detected a booking for the official in a London hotel, and dispatched at least ten undercover agents to London. The agents were split into three teams. One group was sent to Heathrow Airport to identify the official as he arrived, a second to book into his hotel, and a third to monitor his movements and visitors. Some of the operatives were from the Kidon Division, which specializes in assassinations, and the Neviot Division, which specializes in breaking into homes, embassies, and hotel rooms to install bugging devices. On the first day of his visit, he visited the Syrian embassy and then went shopping. Kidon operatives closely followed him, while Neviot operatives broke into his hotel room and found his laptop. A computer expert then installed software that allowed the Mossad to monitor his activities on the computer. When the computer material was examined at Mossad headquarters, officials found blueprints and hundreds of pictures of the Kibar facility in various stages of construction, and correspondence. One photograph showed North Korean nuclear official Chon Chibu meeting with Ibrahim Othman, Syria's atomic energy agency director. Though the Mossad had originally planned to kill the official in London, it was decided to spare his life following the discovery.[28] Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert was notified. The following month, Olmert formed a three-member panel to report on Syria's nuclear program. The CIA was also informed and the American intelligence network joined the quest for more information.[27] Six months later, Brigadier-General Yaakov Amidror, one of the panel's members, informed Olmert that Syria was working with North Korea and Iran on a nuclear facility. Iran had funneled $1 billion to the project, and planned on using the Kibar facility to replace Iranian facilities if Iran was unable to complete its uranium enrichment program.[26]

In July 2007, an explosion occurred in Musalmiya, northern Syria. The official Sana news agency said 15 Syrian military personnel were killed and 50 people were injured. The agency reported only that "very explosive products" blew up after a fire broke out at the facility. The edition of 26 September of Jane's Defence Weekly claimed that the explosion happened during tests to weaponise a Scud-C missile with mustard gas.[29]

A senior U.S. official told ABC News that, in early summer 2007, Israel had discovered a suspected Syrian nuclear facility, and that the Mossad then "managed to either co-opt one of the facility's workers or to insert a spy posing as an employee" at the suspected Syrian nuclear site, and through this was able to get pictures of the target from on the ground."[30]

In mid August 2007, Israeli commandos from the Sayeret Matkal reconnaissance unit covertly raided the suspected Syrian nuclear facility and brought nuclear material back to Israel. Two helicopters ferried twelve commandos to the site in order to get photographic evidence and soil samples. The commandos were probably dressed in Syrian uniforms. Although the mission was successful, it had to be aborted earlier than planned after the Israelis were spotted by Syrian soldiers. Soil analysis revealed traces of nuclear activity.[26][31][32] There was disagreement between CIA director Michael Hayden and Mossad director Meir Dagan about whether the site should be bombed. Hayden was fearful that this would cause an all-out war, but Dagan was sure that Assad would not react, so long as the bombing was done covertly and not publicized.[27] Anonymous sources reported that once material was tested and confirmed to have come from North Korea, the United States approved an Israeli attack on the site.[23] Senior U.S. officials later claimed that they were not involved in or approved the attack, but were informed in advance.[33] In his memoir Decision Points, President George W. Bush wrote that Prime Minister Olmert requested that the U.S. bomb the Syrian site, but Bush refused, saying the intelligence was not definitive on whether the plant was part of a nuclear weapons program. Bush claimed that Olmert did not ask for a green light for an attack and that he did not give one, but that Olmert acted alone and did what he thought was necessary to protect Israel.[17] Another report indicated that Israel planned to attack the site as early as 14 July, but some U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, preferred a public condemnation of Syria, thereby delaying the military strike until Israel feared the information would leak to the press.[34] The Sunday Times also reported that the mission was "personally directed" by Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak.[23]

Three days before the attack, a North Korean cargo ship carrying materials labeled as cement docked in the Syrian port of Tartus.[35] An Israeli online data analyst, Ronen Solomon, found an internet trace for the 1,700-tonne cargo ship, the Al Hamed, which allegedly was docked at Tartus on 3 September.[36] By 25 April 2008 the ship was under the flag of the Comoros.[37]

Several newspapers reported that Iranian general Ali Reza Asgari, who had disappeared in February in a possible defection to the West, supplied Western intelligence with information about the site.[38][39]

Target

CNN first reported that the airstrike targeted weapons "destined for Hezbollah militants" and that the strike "left a big hole in the desert".[40] One week later, The Washington Post reported that U.S. and Israeli intelligence gathered information on a nuclear facility constructed in Syria with North Korean aid, and that the target was a "facility capable of making unconventional weapons".[41] According to The Sunday Times, there were claims of a cache of nuclear materials from North Korea.[19]

Syrian Vice-President Faruq Al Shara announced on 30 September that the Israeli target was the Arab Center for the Studies of Arid Zones and Dry Lands, but the center itself immediately denied this.[42] The following day Syrian President Bashar al-Assad described the bombing target as an "incomplete and empty military complex that was still under construction". He did not provide any further details about the nature of the structure or its purpose.[43]

On 14 October The New York Times cited U.S. and Israeli military intelligence sources saying that the target had been a nuclear reactor under construction by North Korean technicians, with a number of the technicians having been killed in the strike.[44] On 2 December The Sunday Times quoted Uzi Even, a professor at Tel Aviv University and a founder of the Negev Nuclear Research Center, saying that he believes that the Syrian site was built to process plutonium and assemble a nuclear bomb, using weapons-grade plutonium originally from North Korea. He also said that Syria's quick burial of the target site with tons of soil was a reaction to fears of radiation.[45]

On 19 March 2009, Hans Rühle, former chief of the planning staff of the German Defense Ministry, wrote in the Swiss daily Neue Zürcher Zeitung that Iran was financing a Syrian nuclear reactor. Rühle did not identify the sources of his information. He wrote that U.S. intelligence had detected North Korean ship deliveries of construction supplies to Syria that started in 2002, and that the construction was spotted by American satellites in 2003, who detected nothing unusual, partly because the Syrians had banned radio and telephones from the site and handled communications solely by messengers. He said that "The analysis was conclusive that it was a North Korean-type reactor, a gas graphite model" and that "Israel estimates that Iran had paid North Korea between $1 billion and $2 billion for the project". He also wrote that just before the Israeli operation, a North Korean ship was intercepted en route to Syria with nuclear fuel rods.[32]

The Operation

Ten Israeli F-15I Ra'am fighter jets (including aircraft '209') from the Israeli Air Force 69th Squadron armed with laser-guided bombs, escorted by F-16I Sufa fighter jets – including aircraft '432' from 253rd squadron and '459' from 119th squadron– and a few ELINT aircraft, took off from Ramat David Airbase. Three of the F-15s were ordered back to base, while the remaining seven continued towards Syria. The Israelis destroyed a Syrian radar site in Tall al-Abuad with conventional precision bombs, electronic attack, and jamming.[46]

Electronic warfare

Israel reportedly used electronic warfare to take over Syrian air-defenses and feed them a false-sky picture,[24] for the entire period of time that the Israeli fighter jets needed to cross Syria, bomb their target and return.[25] This technology which neutralized Syrian radars may be similar to the Suter airborne network attack system. This would make it possible to feed enemy radar emitters with false targets, and even directly manipulate enemy sensors.[47][48] In May 2008, a report in IEEE Spectrum cited European sources claiming that the Syrian air defense network had been deactivated by a secret built-in kill switch activated by the Israelis.[49][50]

When the aircraft approached the site, the Shaldag commandos directed their targeting laser at the facility, and the F-15Is released their bombs. The facility was totally destroyed.[51]

The Shaldag commandos were extracted, and all Israeli aircraft returned to base. On their way back to Israel, the aircraft flew over Turkey and jettisoned fuel tanks over the Hatay and Gaziantep provinces.

Immediately following the attack, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert called Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, explained the situation, and asked him to relay a message to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad that Israel would not tolerate another nuclear plant, but that no further action was planned. Olmert said that Israel did not want to play up the incident and was still interested in peace with Syria, adding that if Assad chose not to draw attention to the incident, he would do likewise.

Israeli official statements

The first report about the raid came from CNN. Israel initially did not comment on the incident, although Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert did say that "The security services and Israeli defence forces are demonstrating unusual courage. We naturally cannot always show the public our cards."[52] Israeli papers were banned from doing their own reporting on the airstrike.[53] On 16 September, the head of Israeli military intelligence, Amos Yadlin, told a parliamentary committee that Israel regained its "deterrent capability".[54]

The first public acknowledgment by an Israeli official came on 19 September, when opposition leader Benjamin Netanyahu said that he had backed the operation and congratulated Prime Minister Olmert.[55] Netanyahu advisor Uzi Arad later told Newsweek "I do know what happened, and when it comes out it will stun everyone."[56]

On 17 September, Prime Minister Olmert announced that he was ready to make peace with Syria "without preset conditions and without ultimatums".[57] According to a poll done by the Dahaf Research Institute, Olmert's approval rating rose from 25% to 35% after the airstrike.[58]

On 2 October 2007, the IDF confirmed the attack took place, following a request by Haaretz to lift censorship; however, the IDF continued to censor details of the actual strike force and its target.[59]

On 28 October, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert told the Israeli cabinet that he had apologized to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan if Israel violated Turkish airspace. In a statement released to the press after the meeting he said: "In my conversation with the Turkish prime minister, I told him that if Israeli planes indeed penetrated Turkish airspace, then there was no intention thereby, either in advance or in any case, to—in any way—violate or undermine Turkish sovereignty, which we respect."[60]

Syrian reaction

Abu Mohammed, a former major in the Syrian air force, recounted in 2013 that air defenses in the Deir ez-Zor region were told to stand down as soon as the Israeli planes were detected heading to the reactor.[61]

According to a WikiLeaks cable, the Syrian government placed long-range missiles armed with chemical warheads on high alert after the attack but did not retaliate, fearing an Israeli nuclear counterstrike.[62]

Syria at first claimed that its anti-aircraft weapons had fired at Israeli planes, which bombed empty areas in the desert,[63] or later, a military construction site.[64] During the two days following the attack, Turkish media reported finding Israeli fuel tanks in Hatay and Gaziantep Province, and the Turkish Foreign Minister lodged a formal protest with the Israeli envoy.[63][65]

In a letter to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon, Syria called the incursion a "breach of airspace of the Syrian Arab Republic" and said "it is not the first time Israel has violated" Syrian airspace. Syria also accused the international community of ignoring Israeli actions. A UN spokesperson said Syria had not requested a meeting of the UN Security Council and France, at the time the president of the Security Council, said it had received no letter from Syria.[66]

On 27 April 2008, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, making his first public comments about the raid, dismissed the allegations that it was a nuclear site which was attacked as false: "Is it logical? A nuclear site did not have protection with surface to air defenses? A nuclear site within the footprint of satellites in the middle of Syria in an open area in the desert?" Independent experts, however, suggested that Syria did not fortify its suspected reactor in order to avoid drawing attention and because the building was not yet operational. Besides a nuclear program, Syria is believed to have extensive arsenals, as well as biological and chemical warheads for its long-range missiles.[67][68] On 25 February 2009, IAEA officials reported that Ibrahim Othman, Syria's nuclear chief, told a closed IAEA technical meeting that Syria built a missile facility on the site.[69]

International reactions

No Arab government besides Syria has formally commented on 6 September incident. The Egyptian weekly Al-Ahram commented on the "synchronized silence of the Arab world." Neither the Israeli nor Syrian government has offered a detailed description of what occurred. Outside experts and media commentators have filled the data vacuum by offering their own diverse interpretations about what precisely happened that night. Western commentators took the position that the lack of official non-Syrian Arab condemnations of Israel's action, threats of retaliation against Israel, or even professions of support for the Syrian government or people must imply that their governments tacitly supported the Israeli action. Even Iranian officials have not formally commented on the Israeli attack or Syria's reactions.[70]

U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates was asked if North Korea was helping Syria in the nuclear realm, but replied only that "we are watching the North Koreans very carefully. We watch the Syrians very carefully."[71]

The North Korean government strongly condemned Israel's actions: "This is a very dangerous provocation little short of wantonly violating the sovereignty of Syria and seriously harassing the regional peace and security."[72]

On 17 October, in reaction to the UN press office's release of a First Committee, Disarmament and International Security meeting's minutes that paraphrased an unnamed Syrian representative as saying that a nuclear facility was hit by the raid, Syria denied the statement, adding that "such facilities do not exist in Syria." However state-run Syrian Arab News Agency said that media reports had misquoted the Syrian diplomat.[60]

On the same day, the IAEA's Mohamed ElBaradei criticized the raid, saying that "to bomb first and then ask questions later [...] undermines the system and it doesn't lead to any solution to any suspicion."[73] The IAEA had been observing the disabling of the DPRK Yongbyon nuclear facilities since July 2007, and was responsible for the containment and surveillance of the fuel rods and other nuclear materials from there.[74]

U.S. House Resolution 674, introduced on 24 September 2007, expressed "unequivocal support ... for Israel's right to self defense in the face of an imminent nuclear or military threat from Syria." The bill had 15 cosponsors, but never reached a vote.[75]

On 26 October,The New York Times published satellite photographs showing that the Syrians had almost entirely removed all remains of the facility. U.S. intelligence sources noted that such an operation would usually take up to a year to complete and expressed astonishment at the speed with which it was carried out. Former weapons inspector David Albright believed that the work was meant to hide evidence of wrongdoing.[76][77]

On 28 April 2008, CIA Director Michael Hayden said that a suspected Syrian reactor bombed by Israel had the capacity to produce "enough plutonium for one or two weapons per year", and that it was of a "similar size and technology" to North Korea's Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center.[78]

In his memoir Decision Points, President George W. Bush claimed that the strike confirmed that Syria had been pursuing a nuclear-weapons program and that "intelligence is not an exact science", relating that while he had been told that U.S. analysts only had low confidence that the facility was part of a nuclear-weapons program, surveillance after the airstrike showed parts of the destroyed facility being covered up. Bush wrote that "if the facility was really just an innocent research lab, Syrian President Assad would have been screaming at the Israelis on the floor of the United Nations". He also wrote that in a telephone conversation with Olmert, he suggested that the operation be kept secret for a while and then made public to isolate the Syrian government, but Olmert asked for total secrecy, wanting to avoid anything that might force Syrian retaliation.[17]

In April 2011, after a lengthy investigation the IAEA officially confirmed that the site was a nuclear reactor.[8]

In 2012, the Non-aligned Movement adopted a statement according to which: 'The Heads of State or Government underscored the Movement's principled position concerning non-use or threat of use of force against the territorial integrity of any State. In this regard, they condemned the Israeli attack against a Syrian facility on 6 September 2007, which constitutes a flagrant violation of the UN Charter and welcomed Syria's cooperation with the IAEA in this regard’ (NAM Final Document 2012/Doc.1/Rev.2, para 176).

Release of intelligence

On 10 October 2007, The New York Times reported that the Israelis had shared the Syrian strike dossier with Turkey. In turn, the Turks traveled to Damascus and confronted the Syrians with the dossier, alleging a nuclear program. Syria denied this with vigor, saying that the target was a storage depot for strategic missiles.[79] On 25 October 2007, The New York Times reported that two commercial satellite photos taken before and after the raid showed that a square building no longer exists at the suspected site.[80] On 27 October 2007, The New York Times reported that the imaging company Geoeye released an image of the building from 16 September 2003, and from this security analyst John Pike estimated that construction began in 2001. "A senior intelligence official" also told The New York Times that the U.S. has observed the site for years by spy satellite.[81] Subsequent searches of satellite imagery discovered that an astronaut aboard the International Space Station had taken a picture of the area on 5 September 2002. The image, though of low resolution, is good enough to show that the building existed as of that date.

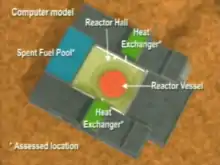

On 11 January 2008, DigitalGlobe released a satellite photo showing that a building similar to the suspected target of the attack had been rebuilt in the same location.[82] However, an outside expert said that it was unlikely to be a reactor and could be cover for excavation of the old site.[83] On 1 April 2008, Asahi Shimbun reported that Ehud Olmert told Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda during a meeting on 27 February that the target of the strike was "nuclear-related facility that was under construction with know-how and assistance from North Korean technicians dispatched by Pyongyang."[84] On 24 April 2008, the CIA released a video[85] and background briefing,[86] which it claims shows similarities between the North Korean nuclear reactor in Yongbyon and the one in Syria which was bombed by Israel.[87] According to a U.S. official, there did not appear to be any uranium at the reactor, and although it was almost completed, it could not have been declared operational without significant testing.[88]

A statement from the White House Press Secretary on 24 April 2008, followed the briefing given to some Congressional committees that week. According to the statement, the administration believed that Syria had been building a covert reactor with North Korean assistance that was capable of producing plutonium, and that the purpose was non-peaceful. It was also stated that the IAEA was being briefed with the intelligence.[89] The IAEA confirmed receipt of the information, and planned to investigate. It was critical of not being informed earlier, and described the unilateral use of force as "undermining the due process of verification".[90]

Syrian officials, however, denied any North Korean involvement in their country. According to BBC News, Syria's ambassador to the UK, Sami Khiyami, dismissed the allegations as ridiculous. "We are used to such allegations now, since the day the United States has invaded Iraq – you remember all the theatrical presentations concerning the weapons of mass destruction in Iraq." Mr Khiyami said the facility was a deserted military building that had "nothing to do with a reactor".[91]

On 21 March 2018, Israel formally acknowledged the operation and released newly declassified materials including photographs and cockpit video of the airstrike.[16]

Initial skepticism about the US and Israeli claims

Despite the release of intelligence information from the American and Israeli sources, the attack on the Syrian site was initially controversial. Some commentators had argued that at the time of the attack the site had no obvious barbed wire or air defenses that would normally ring a sensitive military facility.[92] Mohamed ElBaradei had previously stated that Syria's ability to construct and run a complex nuclear process was doubtful—speaking ahead of the IAEA inspection of the alleged Syrian nuclear site, which had been demolished, he said: "It is doubtful we will find anything there now, assuming there was anything in the first place."[93] The New York Times reported that after the publishing of US intelligence data on 24 April, "two senior intelligence officials acknowledged that the evidence had left them with no more than "low confidence" that Syria was preparing to build a nuclear weapon. However, while they said that there was no sign that Syria had built an operation to convert the spent fuel from the plant into weapons-grade plutonium, they had told President Bush last year that they could think of no other explanation for the reactor."[94] BBC Diplomatic Correspondent Jonathan Marcus commented on the release of the CIA video that "Briefings about alleged weapons of mass destruction programmes have a lot to live down in the wake of the US experience in Iraq".[95]

Aftermath

IAEA investigation

On 19 November 2008, IAEA released a report[96] which said the Syrian complex bore features resembling those of an undeclared nuclear reactor and UN inspectors found "significant" traces of uranium at the site. The report said the findings gleaned from inspectors' visit to the site in June were not enough to conclude a reactor was once there. It said further investigation and greater Syrian transparency were needed. The confidential nuclear safeguards report said Syria would be asked to show to inspectors debris and equipment whisked away from the site after the September 2007 Israeli air raid.[97]

On 19 February 2009, the IAEA reported that samples taken from the site revealed new traces of processed uranium. A senior UN official said additional analysis of the June find had found 40 more uranium particles, for a total of 80 particles, and described it as significant. He added that experts were analyzing minute traces of graphite and stainless steel found at and near the site, but said that it was too early to relate them to nuclear activity. The report noted Syria's refusal to allow agency inspectors to make follow-up visits to sites suspected of harboring a secret nuclear program despite repeated requests from top agency officials.[98] Syria disputed these claims. According to Syria's IAEA representative Othman, there would have been a large amount of graphite had the building been a nuclear reactor. Othman continued, "They found 80 particles in half a million tonnes of soil. I don't know how you can use that figure to accuse somebody of building such a facility."[15]

In a November 2009 report, the IAEA stated that its investigation had been stymied due to Syria's failure to cooperate.[14] The following February, under the new leadership of Yukiya Amano, the IAEA stated that "The presence of such [uranium] particles points to the possibility of nuclear-related activities at the site and adds to questions concerning the nature of the destroyed building. ... Syria has yet to provide a satisfactory explanation for the origin and presence of these particles".[99] Syria disputed these allegations, saying that there is not a military nuclear program in the country and that it has the right to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, especially in the field of nuclear medicine. Syria's foreign minister said, "We are committed to the non-proliferation agreement between the agency and Syria and we (only) allow inspectors to come according to this agreement. ... We will not allow anything beyond the agreement because Syria does not have a military nuclear program. Syria is not obliged to open its other sites to inspectors."[100] Syria maintains that the natural uranium found at the site came from Israeli missiles.[101] On 28 April 2010, the head of the IAEA, Yukiya Amano declared for the first time that the target was indeed the covert site of a future nuclear reactor, countering Syrian assertions.[102]

The site during Syrian Civil War

During the Syrian Civil War, the reactor site fell to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) militant group in May 2014. On 6 March 2017, the site was captured by the Syrian Democratic Forces – a U.S.-backed coalition of Kurdish and Arab militia fighters. Since then, the site has remained inside the territory governed by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.[103]

Claiming responsibility

On 22 March 2018, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officially took responsibility for destroying a nuclear reactor built in the northeastern Syrian province of Deir al-Zor in 2007 after a decade of ambiguity.[104]

See also

References

- "Ending a decade of silence, Israel confirms it blew up Assad's nuclear reactor".

- Tak Kumakura (28 April 2008). "North Koreans May Have Died in Israel Attack on Syria, NHK Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- Beaumont, Peter (16 September 2007). "Was Israeli raid a dry run for attack on Iran?". The Observer/The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- Stephens, Bret (18 September 2007). "Osirak II". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- IAEA: Syria tried to build nuclear reactor Associated Press Latest Update: 04.28.11, 18:10

- "Officials say Israel raid on Syria triggered by arms fears". Reuters. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Leonard S. Spector and Avner Cohen, Israel's Airstrike on Syria's Reactor: Implications for the Nonproliferation Regime, Arms Control Today, Vol. 38, No. 6 (July/August 2008), pp. 15–21, Arms Control Association

- "NKorea-Syria nuclear work had military aims: White House". Associated French Press. 24 April 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- "Syria denies US allegations over nuclear reactor". Syria Today. May 2008. ISSN 1812-8637. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- Heinrich, Mark (19 February 2009). "IAEA finds graphite, further uranium at Syria site". Vienna. Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- "IAEA inspects nuclear research reactor in Syria". AFP. 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- "AFP: No graphite found by IAEA at suspect site: Syria". Vienna: Google. 24 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- "Israel formally acknowledges destroying suspected Syrian reactor in..." Reuters. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- George W. Bush, Decision Points, London: Random House, 2010, p. 421–422

- Country Profiles—Israel Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), updated May 2014

- Mahnaimi, Uzi (16 September 2007). "Israelis 'blew apart Syrian nuclear cache'". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- "Ending a decade of silence, Israel confirms it blew up Assad's nuclear reactor". Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Hersh, Seymour. "A Strike in the Dark", The New Yorker, 11 February 2008. Retrieved on 7 February 2008.

- "Turkish FM slams Israel over fuel tanks". The Jerusalem Post. 10 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- Mahnaimi, Uzi (23 September 2007). "Snatched: Israeli commandos 'nuclear' raid". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Israel Shows Electronic Prowess 26 November 2007, David A. Fulghum and Robert Wall, Aviation Week & Space Technology

- By YAAKOV KATZ, 29 September 2010, Jerusalem Post

- Klieger, Noah (11 February 2009). "A strike in the desert". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Ronen Bergman (30 December 2016). "Ex-CIA director: I was sure if we didn't strike Syria's nuclear reactor, Israel would". Yedioth Ahronoth. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016.

- Gardham, Duncan (15 May 2011). "Mossad carries out daring London raid on Syrian official". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011.

- "Syria blast 'linked to chemical weapons': report". Agence France-Presse (AFP). 19 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- Raddatz, Martha (19 October 2007). "EXCLUSIVE: The Case for Israel's Strike on Syria". ABC News. Agence France-Presse (AFP). Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- "Snatched: Israeli commandos 'nuclear' find". The Times. 23 September 2007.

- "'Iran defector tipped off U.S. on Syrian nuclear ambitions'". Haaretz. Associated Press. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- Hess, Pamela (23 April 2008). "White House says Syria 'must come clean' about nuclear work". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "Report: Turkish FM to discuss Syria in J'lem". The Jerusalem Post. 6 October 2007. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- Kessler, Glenn (15 September 2007). "Syria-N. Korea Reports Won't Stop Talks". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Butcher, Tim (17 September 2007). "N Korean ship 'linked to Israel's strike on Syria'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- e-ships.net database, Retrieved 24 April 2008

- "Report: Defecting Iranian official gave info before alleged Syrian foray". The Jerusalem Post. 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- Rühle, Hans (19 March 2009). "Wie Iran Syriens Nuklearbewaffnung vorangetrieben hat". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- "Syria complains to U.N. about Israeli airstrike". CNN. 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- Kessler, Glenn (13 September 2007). "N. Korea, Syria May Be at Work on Nuclear Facility". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "Arab League center denies it was Israeli raid target". Middle East Times. 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- "Assad sets conference conditions". BBC News. 1 October 2007. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- Sanger, David E. (14 October 2007). "Israel Struck Syrian Nuclear Project, Analysts Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- Mahnaimi, Uzi (2 December 2007). "Israelis hit Syrian 'nuclear bomb plant'". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- Fulghum, David A. (27 November 2007). "U.S. Electronic Surveillance Monitored Israeli Attack On Syria". World Security Network. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Fulghum, David A (3 October 2007). "Why Syria's Air Defenses Failed to Detect Israelis". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Fulghum, David A (8 October 2007). "Israel used electronic attack in air strike against Syrian mystery target". ABC News. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- Sally Adee, "The Hunt for the Kill Switch", IEEE Spectrum, May 2008.

- Markoff, John (26 September 2010). "Stuxnet Worm Is Remarkable for Its Lack of Subtlety". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Israel thwarted Syria's plan to attack on YouTube infolivetivenglish, 17 September 2007

- Urquhart, Conal (17 September 2007). "Speculation flourishes over Israel's strike on Syria". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- Harel, Amos (16 September 2007). "ANALYSIS: Mummed media base IAF strike reports on world press". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Israel says deterrent ability recovered after Syria strike". Associated French Press. 16 September 2007. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "Netanyahu says Israel carried out Syria air raid, he backed it". Associated French Press. 19 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- Ephron, Dan (22 September 2007). "The Whispers of War". Newsweek. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "Olmert says he is ready to make peace with Syria". The Jerusalem Post. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- "Mysterious airstrike in northern Syria boosts Olmert's popularity: Poll". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 18 September 2007. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- Oren, Amir (2 October 2007). "IDF lifts censorship on air strike against Syria target". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ""USAF struck Syrian "Nuclear" site". Information Clearing House. 2 November 2007. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- Chulov, Martin (4 February 2013). "Syrian rebel raids expose secrets of once-feared military". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Bergman, Ronen (14 April 2014). "WikiLeaks: Syria aimed chemical weapons at Israel". Ynet News. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "Turkey Asks Israel About Fuel Tanks". Associated Press. 9 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ""Israel admits air strike on Syria". BBC News. 2 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "Turkey complains to Israel over fuel tanks found near border with Syria: reports". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 9 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- "Syria complains to U.N. about Israeli airstrike". CNN. 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- Breaking News – JTA, Jewish & Israel News

- "Assad says facility Israel bombed not nuclear-paper". Reuters. 27 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012.

- Broad, William J. (25 February 2009). "Syria Discloses Missile Facility, Europeans Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Weitz, Richard. "Israeli Airstrike in Syria: International Reactions Archived 1 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Monterey Institute of International Studies (MIIS), 1 November 2007.

- "Speculation heats up over what Israel hit in Syria". Associated French Press. 16 September 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "Israel Condemned for Intrusion into Syria's Territorial Air". Kcna.co.jp. 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ""IAEA chief criticizes Israel over Syria raid". Reuters. 10 October 2007. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "IAEA: Implementation of Safeguards in the DPRK". Vienna: IAEA: Statements of the Director General. 3 March 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "Bill H. Res. 674: Expressing the unequivocal support of the House of Representatives for Israel's right to self...", U.S. House of Representatives, bill introduced 24 September 2007.

- "Alleged Syrian atomic reactor 'vanishes'". The Jerusalem Post. 26 October 2007. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "Syria Update II: Syria Buries Foundation of Suspect Reactor Site" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. 26 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- Editorial, Reuters. "UPDATE 2-Syrian reactor capacity was 1-2 weapons/year -CIA".

- Mazzetti, Mark; Cooper, Helene (10 October 2007). "An Israeli Strike on Syria Kindles Debate in the U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013.

- Broad, William (26 October 2007). "Satellite Photos Show Cleansing of Suspect Syrian Site". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- Broad, William; Mazzetti, Mark (27 October 2007). "Yet Another Photo of Site in Syria, Yet More Questions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Broad, William (12 January 2008). "Syria Rebuilds on Site Destroyed by Israeli Bombs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- Mikkelsen, Randall (15 January 2008). "Syria rebuilding at site bombed by Israel – report". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- "Report: Olmert admitted Israel struck Syrian nuclear facility". Ynetnews. 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- "CIA footage in full". BBC News. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- "Background Briefing with Senior U.S. Officials on Syria's Covert Nuclear Reactor and North Korea's Involvement" (PDF). Director of National Intelligence. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wright, Robin (24 April 2008). "N. Koreans Taped At Syrian Reactor". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "US shows evidence of alleged Syria-N. Korea nuke collaboration". Associated Press. 24 April 2008.

- "Statement by the Press Secretary" (Press release). White House. 24 April 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- "Press Release 2008/06: Statement by IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei". IAEA. 25 April 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "Syria 'had covert nuclear scheme'". BBC News. 25 April 2008. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Broad, William J. (12 January 2008). "Syria Rebuilds on Site Destroyed by Israeli Bombs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Reynolds, Paul (23 June 2008). "Will Syrian site mystery be solved?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Sanger, David E. (25 April 2008). "Bush Administration Releases Images to Bolster Its Claims About Syrian Reactor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Marcus, Jonathan (25 April 2008). "US Syria claims raise wider doubts". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Syrian Arab Republic" (PDF). IAEA. 19 November 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Syria site hit by Israel resembled atom plant: IAEA". Reuters. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- "UN agency finds new uranium traces at Syrian site". The International Herald Tribune. 19 February 2009. ISSN 0294-8052. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- Heinrich, Mark (18 February 2010). "IAEA suspects Syrian nuclear activity at bombed site". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- "Syria dismisses IAEA call for more inspectors access". ynetnews.com. Reuters. 20 February 2010.

- "Syria Rules Out Further IAEA Access to Suspected Nuclear Site". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011.

- "Syria target hit by Israel was 'nuclear site'". Al Jazeera. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Chris Tomson (6 March 2017). "Kurdish forces seize military base from ISIS amid massive offensive in Deir Ezzor". Al-Masdar News. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

Further reading

- Makovsky, David (17 September 2012). "The Silent Strike: How Israel bombed a Syrian nuclear installation and kept it secret". The New Yorker.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Orchard. |

- Globalsecurity.org 06 September 2007 Airstrike

- Report: US stalled Israeli strike on Syria

- Report: Israel 'blinded' Syrian radar

- A Sourcebook on the Israeli Strike in Syria

- U.S. Government video (length 11:38 49.8 MB) via veoh.com

- Der Spiegel 2 November 2009 Report: The Story of 'Operation Orchard'

- The long road to Syria, Ynetnews