Oil shale in Jordan

Oil shale in Jordan represents a significant resource. Oil shale deposits in Jordan underlie more than 70% of Jordanian territory. The total resources amounts to 31 billion tonnes of oil shale.[1]

The deposits include a high quality marinite oil shale of Late Cretaceous to early Cenozoic age.[2] The most important and investigated deposits are located in west-central Jordan, where they occur at the surface and close to developed infrastructure.[3][4]

Although oil shale was utilized in northern Jordan prior to and during World War I, intensive exploration and studies of Jordan's oil shale resource potential started in the 1970s and 1980s, being motivated by higher oil prices, modern technology and better economic potential. As of 2008, no oil shale industry exists in Jordan, but several companies are considering both shale oil extraction and oil shale combustion for thermal power generation.[5]

Reserves

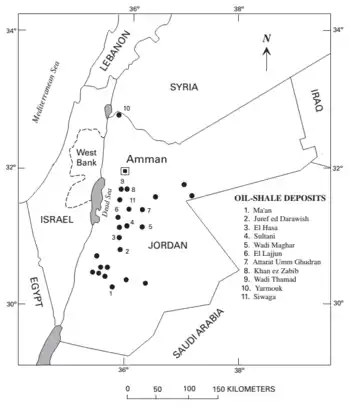

Jordan has significant oil shale deposits occurring in 26 known localities. According to the World Energy Council, Jordan has 8th largest oil shale resource in the world.[6] Geological surveys indicate that the existing deposits underlie more than 60% of Jordan's territory. The resource has been estimated to consist of 40 to 70 billion tonnes of oil shale, which may be equivalent to more than 5 million tonnes of shale oil.[3][4][6][7] However, according to a report by World Energy Council in 2010, Jordan had reserves of 34,172 billion tonnes as of the end of 2008.[8] The Jordanian government said in September 2013 that they had reserves of 31 billion tonnes.[1]

The Jordanian oil shale is a marinite of Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) to early Cenozoic era; it lies within the Muwaqqar Formation and is composed predominantly of chalk and marl. The rock is typically brown, gray, or black in color and weathers to a distinctive light bluish-gray. It is characterized by its content of light fine-grained phosphatic xenocrysts, some of which is accumulated in bone beds.[4] An uncommon feature of Jordanian oil shale is that the included foraminiferal shells are filled with bitumen instead of the usual calcite.[2]

In general Jordanian oil shales are of high quality, comparable to the western United States oil shale, although their sulfur content is usually higher. While the sulfur content of the most of oil shales in Jordan varies from 0.3 to 4.3%, the Jurf ed Darawish and the Sultani deposits have sulfur content of 8 and 10% respectively.[3] Sulfur is mostly associated with the organic matter with minor occurrence as pyrite.[9] The moisture content of the oil shale is low (2 to 5.5%). The major mineral components of the Jordanian oil shale are calcite, quartz, kaolinite, and apatite, along with small amounts of dolomite, feldspar, pyrite, illite, goethite, and gypsum. It has also a relatively high metal content.[3]

The eight most important deposits are located in west-central Jordan within 20 to 75 kilometres (12 to 47 mi) east of the Dead Sea. These deposits are Juref ed Darawish, Sultani, Wadi Maghar, El Lajjun, Attarat Umm Ghudran, Khan ez Zabib, Siwaga, and Wadi Thamad. The best-explored deposits are El Lajjun, Sultani, and Juref ed Darawish, and to some extent Attarat Umm Ghudran.[3][4] They are all classified as shallow and most are suitable for open-cast mining, albeit some are underlain by phosphate beds.[6] In addition to the west-central deposits, another important deposit may be the Yarmouk deposit occurring near Jordan's northern border, and where the resource was first developed.[3][4] This deposit would be exploitable by underground mining as it reaches some 400 metres (1,310 ft) in thickness.[6] A third oil shale region lies in southern Jordan in the Ma'an district.[4]

History

Humans have used oil shale as a fuel since prehistoric times, because it generally burns without any processing.[10] Its occurrence was known in Jordan from ancient times, as evidenced by its use as a building and decorative material from the ancient Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad and Abbasid periods. The modern exploitation of Jordanian oil shale began under Ottoman rule prior to and during World War I, when the German Army produced shale oil from the Yarmouk area. The oil shale was processed to operate the Hejaz Railway. It was mined and processed near the Maqarin station along the Haifa spur of the railroad, which partly follows the Yarmouk River valley.[2][4] In addition to the shale oil production, oil shale was also utilized as a mix with coal to fuel locomotives.[4]

The German Geological Mission studied the El Lajjun deposit in 1968. In 1979, the Natural Resources Authority of Jordan commissioned a study from the German Federal Institute of Natural Resources and Geosciences to evaluate the Juref ed Darawish, Sultani, El Lajjun, and El Hisa deposits and in 1980 from Klöckner-Lurgi to evaluate the pre-feasibility of construction of an oil shale retorting complex using Lurgi-Ruhrgas process and a power plant with 300 MW capacity using Lurgi's Circulating Fluidized Bed (CFB) combustion process.[4][7][11] In 1980, the Soviet Technopromexport company conducted a pre-feasibility study of the 300–400 direct-burning conventional combustion power plant.[11] In 1986, updated and expanded studies were ordered from Klöckner-Lurgi.[4][7]

In 1985–1986, Chinese oil company Sinopec carried out a test for processing El Lajjun oil shale utilizing the Fushun-type retort. Although this process was technically viable, the cooperation with Sinopec was halted due to high operation costs. B.B.C, Lummus/Combustion Eng. and Bechtel Pyropower carried out the CIDA and USAID funded study of utilizing Sultani oil shale for direct combustion in CFB power plants.[4][7]

The Krzhizhanovsky Power Engineering Institute (ENIN) conducted processing tests of Jordan oil shale using Galoter technology, finding the technology suitable.[11][12] In 1999, Suncor Energy signed a memorandum of understanding with the Jordanian government to use the Alberta Taciuk Processing technology to exploit the El Lajjun oil shale deposit.[13] However, the project was never implemented.

Shale oil extraction

In 2006–2007, the government of Jordan signed four memorandums of understanding for above-ground processing of shale oil and one memorandum for in-situ conversion processing. The memorandum of understanding with Estonian energy company Eesti Energia was signed on 5 November 2006. According to the agreement, Eesti Energia was awarded with the exclusive right to study about one third of the resources of the El Lajjun oil shale deposit.[14][15] Later this right was transferred to cover a block on the Attarat Umm Ghudran oil shale deposit as the shallow aquifer that underlies the El Lajjun deposit provides fresh water to Amman and other municipalities in central Jordan.[16] On 29 April 2008, Eesti Energia present a feasibility study to the Government of Jordan. According to the feasibility study, the company's subsidiary the Jordan Oil Shale Energy Company will establish a shale oil plant with capacity of 36,000 barrels per day (5,700 m3/d).[5] The shale oil plant will use an Enefit processing technology. The concession agreement was signed on 11 May 2010 in the presence of Jordanian and Estonian prime ministers Samir Zaid al-Rifai and Andrus Ansip.[17]

On 24 February 2007, a memorandum of understanding was signed with Brazil's Petrobras awarding with the exclusive right to study a block at the Attarat Umm Ghudran deposit. The development will be carried out in the cooperation with Total S.A. The company will present a feasibility study at the beginning of 2009 and it will use the Petrosix technology.[5]

In June 2006, a memorandum of understanding was signed with Royal Dutch Shell to test its in-situ conversion processing in the Azraq and Al-Jafr blocks of central Jordan. A formal agreement was concluded in February 2009 by which Shell's subsidiary Jordan Oil Shale Company committed to begin commercial operations within 12–20 years.[18] According to the company a decision to invest in a commercial project is unlikely before the late 2020s.[19] It is expected to start production in 2022.[20]

On 9 March 2011, the government of Jordan signed a concession agreement with Karak International Oil, a subsidiary of Jordan Energy and Mining, a project company established for Jordan's oil shale activities. Karak International Oil (KIO) will build a 15,000 barrels per day (2,400 m3/d) shale oil plant in a 35-square-kilometre (14 sq mi) area of El Lajjun in Karak Governorate by 2015.[21][22][23] The company plans to use the Alberta Taciuk Processing technology.[16][24][25]

On 5 November 2006, Saudi Arabian International Corporation for Oil Shale Investment (INCOSIN) signed a memorandum of understanding for evaluation of El Lajjun deposit and Attarat Umm Ghudran resources.[24][26] The concession agreement was approved by the Jordanian government on 3 March 2013. The company cooperates with Russian Atomenergoproekt to utilize the Galoter (UTT-3000) process to build a 30,000 barrels per day (4,800 m3/d) shale oil plant.[27][28] It plans to start production in 2019.[20]

In March 2009, the government of Jordan approved a memorandum of understanding on oil shale extraction with Russian company Inter RAO UES and Aqaba Petroleum Company.[29] Also the Abu Dhabi National Energy Company (TAQA) has shown interest to invest into Jordan's oil shale extraction sector.[30] The memorandum of understanding for exploration in Wadi Al Naadiyeh is ready for signing with the Fushun Mining Group.[31] In 2014, a memorandum of understanding was signed with Al Qamar for Energy and Infrastructure Company.[32]

Power generation

For dealing with increasing power consumption, Jordan plans to utilize oil shale combustion for the power generation. On 30 April 2008, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Jordan, the National Electricity Power Company of Jordan, and Eesti Energia signed an agreement, according to which, Eesti Energia will have the exclusive right to develop the construction of an oil shale-fired power plant with capacity of 460 MW.[33][34][35] It is called Attarat Power Plant and is expected to be operational by 2017.[36] It will be among the largest power stations in Jordan (the largest being Aqaba Thermal Power Plant), and the largest oil shale-fired power plant in the world after Narva Power Plants in Estonia.[35][37]

Inter RAO is planning to build an oil shale-fired power plant with capacity of 90–150 MW.[38]

On 29 September 2013, Jordan and China made a deal to build an oil shale-fired power plant in Karak for $2.5 billion.[1] It will be built by Shandong Electric Power Construction Corporation (SEPCO III), HTJ Group and Al-Lajjun Oil Shale Company.[1] The capacity is 900 MW.[1]

Cement production

In November 2005, a memorandum of understanding was signed with the Jordan Cement Factories Company (JCFC). According to this memorandum, JCFC will utilize El Lajjun oil shale from Karak Governorate for cement production.[39]

References

- "Jordan, China in $2.5 bn deal for oil-shale plant". Fox News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Alali, Jamal (2006-11-07). Jordan Oil Shale, Availability, Distribution, And Investment Opportunity (PDF). International Oil Shale Conference. Amman, Jordan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Dyni, John R. (2006). Geology and resources of some world oil-shale deposits. Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5294 (PDF) (Report). United States Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-13. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

-

Hamarneh, Yousef; Alali, Jamal; Sawaged, Suzan (2006). "Oil Shale Resources Development In Jordan" (PDF). Amman: Natural Resources Authority of Jordan. Retrieved 2008-10-25. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Luck, Taylor (2008-08-07). "Jordan set to tap oil shale potential". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Survey of energy resources (edition 21 ed.). World Energy Council. 2007. pp. 93–115. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.478.9340. ISBN 978-0-946121-26-7.

-

Alali, Jamal; Abu Salah, Abdelfattah; Yasin, Suha M.; Al Omari, Wasfi (2015). "Oil Shale in Jordan" (PDF). Natural Resources Authority of Jordan. Retrieved 2016-05-14. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dyni, John R. (2010). "Oil Shale" (PDF). In Clarke, Alan W.; Trinnaman, Judy A. (eds.). Survey of energy resources (22 ed.). WEC. pp. 93–123. ISBN 978-0-946121-02-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2012-04-22.

- Abed, Abdulkader M.; Arouri, Khaled (2006-11-07). Characterization and genesis of oil shales from Jordan (PDF). International Oil Shale Conference. Amman, Jordan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

-

"Bibliographic Citation: Non-synfuel uses of oil shale". United States Department of Energy. OSTI 6567632. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bsieso, Munther S. (2006-10-16). Oil Shale Resources Development In Jordan (PDF). 26th Oil Shale Symposium. Golden, Colorado. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- Bsieso, Munther S. (2003). "Jordan's experience in oil shale studies employing different technologies" (PDF). Oil Shale. A Scientific-Technical Journal. Estonian Academy Publishers. 20 (3 Special): 360–370. ISSN 0208-189X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- Jaber, J.O.; Mohsen, M.S.; Amr, M. (2001). "Where to with Jordanian oil shales". Oil Shale. A Scientific-Technical Journal. Estonian Academy Publishers. 18 (4): 315–334. ISSN 0208-189X.

- Liive, Sandor (2007). "Oil Shale Energetics in Estonia" (PDF). Oil Shale. A Scientific-Technical Journal. Estonian Academy Publishers. 24 (1): 1–4. ISSN 0208-189X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-01-21. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- "Annual Report 2007/2008" (PDF). Eesti Energia. 2008. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Jordan Oil Shale Project". Omar Al-Ayed, Balqa Applied University. 2008-04-29. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Tere, Juhan (2010-05-12). "Eesti Energia signs oil shale concession agreement with Jordan". The Baltic Course. Archived from the original on 2013-06-30. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- Hazaimeh, Hani (2009-02-25). "Kingdom set to sign oil shale deal with Shell". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "JOSCO's Journey". The Jordan Oil Shale Energy Company. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- Ghazal, Mohammad (2014-03-02). "2018 will be turning point in Jordan's energy sector — minister". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- Hafidh, Hassan (2011-03-09). "UK's JEML Clinches Oil-Shale Deal With Jordan". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones Newswires. Archived from the original on 2011-03-14. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- "Jordan, U.K. company ink oil shale deal". Forbes. Associated Press. 2011-03-09. Archived from the original on 2011-03-12. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- "Oil shale extraction agreement with UK firm approved". The Jordan Times. 2011-10-05. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- Bsieso, Munther S. (2007-10-15). Jordan's Commercial Oil Shale Exploitation Strategy (PDF). 27th Oil Shale Symposium. Golden, Colorado. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-10. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- "Main project description". Jordan Energy and Mining Limited. Archived from the original on 2009-09-23. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- "Company to study viability of oil shale area". The Jordan Times. 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- Blokhin, Alexander; Golmshtok, Edouard; Petrov, Mikhail; Kozhitsev, Dmitriy; Salikhov, Ruslan; Thallab, Hashim (2008-10-15). Adaptation of Galoter Technology for High Sulfurous Oil Shale in Arid Region (PDF). 28th Oil Shale Symposium. Golden, Colorado. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- "Cabinet approves deals for shale oil distillation, oil exploration". The Jordan Times. Petra. 2013-03-03. Archived from the original on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Luck, Taylor (2009-04-01). "Russian, Jordanian firms to explore oil shale potential". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "Abu Dhabi firm expresses interest in investing in oil shale sector". The Jordan Times. 2009-01-13. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Ghazal, Mohammad (2014-01-07). "Chinese company to explore for oil shale in central region". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- Ghazal, Mohammad (2014-11-05). "Planned oil shale project to produce up to 40,000 barrels per day". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- "Jordan's first oil shale power plant expected in 7 years". The Jordan Times. 2008-05-01. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Taimre, Sandra (2008-04-30). "Eesti Energia signed an exclusive contract with Jordan". Baltic Business News. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- "Estonia to build oil shale plant in Jordan" (PDF). The Baltic Times. 2008-05-08. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- "Enefit consortium starts tendering process for Jordan oil shale fired power plant". Jordan News Agency. 2012-06-30. Archived from the original on 2012-07-01. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Bains, Elizabeth (2008-06-01). "Jordan orders oil shale plant". ArabianBusiness.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-02. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- "Inter RAO may join oil shale project in Jordan". Interfax. 2011-02-13. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- Khaled Nuaimat (2005-11-29). "Jordan Cement takes first step to use oil shale in production". Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2008-10-25.