Octavia (play)

Octavia is a Roman tragedy that focuses on three days in the year 62 AD during which Nero divorced and exiled his wife Claudia Octavia and married another (Poppaea Sabina). The play also deals with the irascibility of Nero and his inability to take heed of the philosopher Seneca's advice to rein in his passions.

| Octavia | |

|---|---|

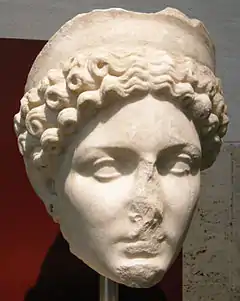

Sculpture portrait of Claudia Octavia | |

| Written by | Unknown |

| Original language | Classical Latin |

| Subject | Divorce of Nero and Octavia |

| Genre | Fabula praetextata (Tragedy based on Roman subjects) |

| Setting | Imperial Rome |

The play was attributed to Seneca, but modern scholarship generally discredits this, since it contains accurate prophecies of both his and Nero’s deaths.[1] While the play closely resembles Seneca's plays in style, it was probably written some time after Seneca's death in the Flavian period by someone influenced by Seneca and aware of the events of his lifetime.[2]

Characters

Plot

Act I

Octavia, weary of her existence, bewails her misery. Her nurse curses the drawbacks which beset life in a Palace. The Nurse consoles Octavia and dissuades her from executing any revenge which she might be contemplating. The Chorus being in favor of Octavia, looks with detestation upon the marriage of Poppaea, and condemns the degenerate patience of the Romans, as being unworthy, too indifferent and servile, and complains about the crimes of Nero.[3]

Act II

Seneca deplores the vices of his times, praises the simplicity of his former life, and offers his opinion that all things are tending to the worse. The philosopher warns his patron Nero but to no purpose. Nero stubbornly insists on carrying out his tyrannical plans, and appoints the next day for his marriage with Poppaea.[3]

Act III

Agrippina appears from the underworld as a cruel soothsayer. She brings torches from the underworld to grace the wedding, and predicts the death of Nero. Octavia urges the populace, who are espousing her cause, not to grieve about her divorce. The Chorus however, does grieve for her sad lot.[3]

Act IV

Poppaea, being frightened in her sleep, narrates her dream to the Nurse. The Nurse treating the dream as nonsense, consoles Poppaea with a shallow interpretation. The Chorus praises the beauty of Poppaea. The Messenger describes the hostile mood of the populace concerning Octavia's divorce and Nero's marriage with Poppaea.[3]

Act V

Nero, boiling over with rage on account of the tumultuous rising of the populace, orders the most severe measures to be taken against them, and that Octavia, as the cause of the rising, shall be transported to Pandataria and there slain. The Chorus sings regarding popular favor, which has been destructive to so many, and after that tells of the hard fates which have befallen the Julio-Claudian dynasty.[3]

References

- R Ferri ed., Octavia (2003) p. 5-9

- H J Rose, A Handbook of Latin Literature (London 1967) p. 375

- Bradshaw, Watson (1903). The ten tragedies of Seneca. S. Sonnenschein & Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Editions

- Otto Zwierlein (ed.), Seneca Tragoedia (Oxford: Clarendon Press: Oxford Classical Texts: 1986)

- Octavia: A Play attributed to Seneca, ed. Rolando Ferri (Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries No.41, Cambridge UP, 2003)

- John G. Fitch Tragedies, Volume II: Oedipus. Agamemnon. Thyestes. Hercules on Oeta. Octavia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: Loeb Classical Library: 2004)

Further reading

- F. L. Lucas, "'The Octavia', an essay," Classical Review, 35,5-6 (1921), 91-93 .

- P. Kragelund, Prophecy, Populism, and Propaganda in the "Octavia" (Copenhagen, 1982).

- T. Barnes, "The Date of the Octavia," MH, 39 (1982) 215-17.

- Harris, W.V., Restraining Rage: The Ideology of Anger Control in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2001).

- T. P. Wiseman, "Octavia and the Phantom Genre," in Idem, Unwritten Rome (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2008).

- Girolamo Cardano 'Nero: An Exemplary Life' Inkstone, 2012.