Nostos: The Return

Nostos: The Return (Italian: Nostos: Il ritorno) is a 1989 Italian adventure drama film directed by Franco Piavoli and starring Luigi Mezzanotte. Drawing from Homer's Odyssey, it is about Odysseus' journey home on the Mediterranean Sea after the Trojan War. The film relies on visual storytelling and the portrayal of nature. There is minimal dialogue and the few spoken lines are in an imaginary Mediterranean language, without subtitles.

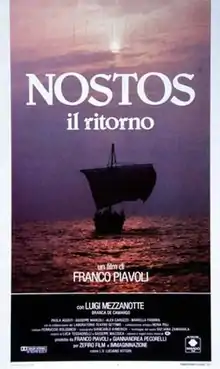

| Nostos: The Return | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Franco Piavoli |

| Produced by | Franco Piavoli Giannandrea Pecorelli |

| Screenplay by | Franco Piavoli |

| Based on | the Odyssey by Homer |

| Starring | Luigi Mezzanotte |

| Music by | Luca Tessadrelli Giuseppe Mazzucca |

| Cinematography | Franco Piavoli |

| Edited by | Franco Piavoli |

Production company | Zefiro Film Immagininazione |

| Distributed by | Mikado Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | fictional; inspired by ancient Greek, Sanskrit and Latin |

The film covers themes of homecoming, the memory of war, man's relationship with nature and Mediterranean culture. Piavoli had been a filmmaker since the 1950s but Nostos: The Return was his first feature-length fiction film. It premiered at the 1989 Locarno Festival before it was released in Italy in 1990.

Plot

Odysseus (Luigi Mezzanotte) is exhausted on a ship together with a handful of men. He has memory flashes of his childhood and of brutal scenes from the Trojan War. The ship stops at a shore and Odysseus explores a cave, where he hears strange singing and stops to call out for his mother.[lower-alpha 1] Returning, he finds his men missing and goes to explore the inland. He walks through a rocky dwelling place populated by nude men and women, seemingly unable to move. He finds a woman who opens a shell and embraces him.[lower-alpha 2] He wakes up in a cave with several sleeping people, including his men, whom he wakes up and sets off with.

The ships sails for a period on the calm sea, but the sound of singing and the brief appearance of a female figure in the water are followed by a sudden storm which wrecks the ship. Odysseus wakes up alone on a beach. Wandering for a while, observing the rich flora and fauna of the location, he meets a woman (Branca De Camargo) who lets him seduce her.[lower-alpha 3] He stays with her but has visual memories of his childhood and homeland.

Odysseus sets off on a simple raft which soon falls apart, and swimming alone in the sea at night he has auditory hallucinations of warfare. The sounds go away and Odysseus focuses on the moon in the sky. He has a vision where he reaches his palace, but the building is a necropolis where he only finds human skulls.

Waking up again on a beach, Odysseus walks across the land and reaches his palace. In the atrium, a girl is rolling a hoop, mirroring a recurring scene from his own memories of childhood. Through a window, he sees the shadow of a woman and quietly mentions the name Penelope.

Themes and analysis

Nostos

Central to Nostos: The Return is the theme of homecoming, which is illustrated throughout the film by images of childhood.[4] The return of Odysseus to his palace—the concept known as nostos in Homer's Odyssey—contains a theme of regained birthright, identity and social position. In Nostos: The Return, this is treated in a discreet and non-violent way, omitting the slaughter of the suitors from the original poem.[3] The film's treatment of memory also differs from Homer's. In Nostos: The Return, the main character's memories of his homeland, childhood and wartime experience appear to be intrinsic to his journey, whereas in the Odyssey, Odysseus continuously struggles against the risk of forgetting.[5] According to the scholar Óscar Lapeña Marchena, the journey in the film can be understood as an attempt to escape from the memory of war and destruction. This is illustrated by the flashback scenes from Troy, where there are no Trojan warriors but only civilians who get killed as they try to flee; at one point the Greek soldiers appear to realize this and look horrified.[6] Aldo Lastella of La Repubblica describes the film's story as "a circular journey, a continuous return" that begins in childhood, goes through the experience of war and violence, and ends in childhood.[7]

Language and symbols

As is typical in the films of the director Franco Piavoli, Nostos: The Return is driven by images and natural sounds rather than dialogue.[8] Spoken dialogue is scarce and, as described in the opening credits, "inspired by sounds of ancient Mediterranean languages".[9] Words and sounds are drawn from the Thessaly dialect of ancient Greek, Sanskrit and Latin.[1] No subtitles are provided for this invented language. Piavoli said he wanted the viewers to lose themselves in the film through "the pleasure of the purely phonetic value of words".[5] The film features single words that may be understood by audiences, such as mater ('mother'), said by Odysseus in the cave early in the film, and oikós ('home'), said when Odysseus is delirious in the sea.[9] The approach to language, according to Lapeña Marchena, suggests a view of the Mediterranean Sea as the originator of several cultures, and an ambition to use language as "primary, pure sounds" recognizable for these cultures.[9] The scholar Silvia Carlorosi likens the film's language to how babies communicate with their mothers. She connects the film's language and imagery to the influence of Giambattista Vico, a philosopher who regarded poetry and metaphors as the original form of human communication, and had a both cyclical and progressive view of history.[10]

According to Piavoli, the child playing with a hoop is a "symbol of time seen as an element that turns in on itself. A child pushing a circle expresses the conception of time as seen by scientists, something circular and linear ... time as a succession of points in an infinite line that runs from the past to the future."[11][lower-alpha 4] The water in the film appears as a symbol for life and for the ability to bring memories and emotions to the surface. The moon occurs throughout Piavoli's filmography as something imposing that brings calm and tranquility. Other visual symbols include the scene where a woman gives Odysseus a shell, representing sex, and a pomegranate and a dove at the end, which are symbols for enduring life and newfound peace.[2]

Nature

Nostos: The Return puts much focus on the movements and visual appearances of nature, which makes the human hero of the story relatively anonymous. He appears as a generic human who goes through an emotional discovery of the natural world.[8] The motif of homecoming co-exists with a theme of man's union with nature; the journey of the main character and the presence of the sea, earth, flowers and the moon suggest a desire for a primitive harmony where humans and nature are one.[4] Lapeña Marchena writes that Piavoli's ambition may have been to go to the source of the myth of Odysseus, located in the nature of the pre-Homeric Mediterranean world.[4] He writes that this may explain why no gods appear as explicit characters on screen: the gods, who in Homer's poem rule over men, animals and plants, may be seen as manifest in nature.[12]

Production

Piavoli had made short films since the 1950s and had a critical success in 1982 with his first feature-length film, the documentary The Blue Planet. His next major film project was Nostos: The Return, which was his first feature-length fiction film.[13] The film takes its basic story material from the ancient Greek epic Odyssey by Homer. Piavoli was especially inspired by book XXIII, which narrates Odysseus' need to convince his wife Penelope of his identity after he returns to his kingdom in Ithaca.[8] The approach to the source material is intentionally ambiguous, and in addition to the Odyssey, there are elements inspired by Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica and Virgil's Aeneid.[14] The film was produced by Piavoli and Giannandrea Pecorelli through the companies Zefiro Film and Immagininazione. It received support from Italy's Ministry of Tourism and Entertainment.[15]

Mezzanotte in the leading role was one of few cast members with previous experience from film and television.[16] Some of the other actors were theatre actors from the Laboratorio Teatro Settimo in Turin and some were non-professionals.[8] The costumes were created by Ferruccio Bolognesi.[15]

Nostos: The Return took one year to prepare and one year to film.[7] The shooting locations were in Sardinia, Lake Garda, the Alps, Veneto, Etruria, Lazio and Sirmione.[8] Scenes from Odysseus' palace were shot at the 16th-century Villa Della Torre in the Province of Verona.[17] To make the sail of the ship look old and worn, it was soaked in gasoline.[8]

Editing took one year; the amount of recorded material corresponded to what was needed for nine films.[18] As with all his films, Piavoli had nearly complete control over the production: in addition to writer and producer, he is credited as director, cinematographer, editor and sound editor.[8] His wife Neria Poli is credited for "artistic collaboration".[15] The soundtrack features original music by Luca Tessadrelli and Giuseppe Mazzucca, as well as music by the composers Gianandrea Gazzola, Luciano Berio, Alexander Borodin, Rudolf Maros and Claudio Monteverdi.[8]

Reception

Nostos: The Return had its world premiere on 6 August 1989 at the Locarno Festival.[7] It was released in Italian cinemas by Mikado Film in 1990.[19]

Alberto Pesce of the Rivista del cinematografo wrote that he was impressed by the visuals and sound alike, and that the various components blend into a beautiful and concrete whole.[19] The film received the OPL Moti Ibrahim award at the 1990 Djerba Festival in Tunisia and the 1990 award of the Turin-based Associazione Italiana Amici del Cinema d'Essai.[13]

References

Notes

- According to Lapeña Marchena, this segment recalls Odysseus' visit to Hades and his meeting with his mother Anticlea.[1]

- Carlorosi identifies the woman with the shell as Circe.[2]

- Piavoli has referred to the woman as Calypso. According to Lapeña Marchena, she is a mix of the Odyssey's Circe, Calypso and Nausicaa.[3]

- Original quotation: "è il simbolo del tempo visto come elemento che gira su se stesso. Il cerchio fatto girare da un bambino esprime entrambe le concezioni del tempo espresso dagli scienziati, quella circolare e quella lineare ... tempo come successione di punti su una linea infinita che corre dal passato al futuro"

Citations

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 101.

- Carlorosi 2015, p. 108.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 102.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 100.

- Carlorosi 2015, p. 105.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, pp. 100–101.

- Lastella 1989.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 98.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 99.

- Carlorosi 2015, pp. 94, 105.

- Faccioli 2003, p. 38, quoted in Carlorosi (2015, p. 108)

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 103.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 97.

- Carlorosi 2015, p. 104.

- Poppi 2000, p. 83.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, p. 106.

- Salvador Ventura 2015, p. 61.

- Lapeña Marchena 2018, pp. 97–98.

- Pesce 1990, p. 17.

Sources

- Carlorosi, Silvia (2015). A Grammar of Cinepoiesis: Poetic Cameras of Italian Cinema. Cine-Aesthetics: New Directions in Film and Philosophy. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0986-2.

- Faccioli, Alessandro (2003). Lo sguardo in ascolto. Il cinema di Franco Piavoli (in Italian). Turin: Kaplan. ISBN 978-88-901231-1-5.

- Lapeña Marchena, Óscar (2018). "Ulysses in the Cinema: The Example of Nostos, il ritorno (Franco Piavoli, Italy, 1990)". In Rovira Guardiola, Rosario (ed.). The Ancient Mediterranean Sea in Modern Visual and Performing Arts: Sailing in Troubled Waters. Imagines – Classical Receptions in the Visual and Performing Arts. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4742-9859-9.

- Lastella, Aldo (1 August 1989). "Torna a casa, uomo!". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Pesce, Alberto (1990). "Nostos, il ritorno, di Franco Piavoli". Rivista del cinematografo (in Italian). 60 (4). Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Poppi, Roberto (2000). "Nostos – Il ritorno". Dizionario del cinema italiano. I film dal 1980 al 1989 (in Italian). 2: M–Z. Rome: Gremese Editore. ISBN 978-88-7742-429-7.

- Salvador Ventura, Francisco (2015). "From Ithaca to Troy: The Homeric City in Cinema and Television". In Garcia Morcillo, Marta; Hanesworth, Pauline; Lapeña Marchena, Óscar (eds.). Imagining Ancient Cities in Film: From Babylon to Cinecittà. Routledge Studies in Ancient History. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-84397-3.

Further reading

- Danese, Roberto M. (2015). "Nostos. Il ritorno di Franco Piavoli. Il mito come intermediazione fra uomo e nature" [Franco Piavoli's Nostos: The Return. Myth as intermediary between man and nature]. Rivista di Cultura Classica e Medioevale (in Italian). 57 (2): 409–430. JSTOR 43923813.

- Maisetti, Massimo (2006). "Νοστος. L'odissea poetica di Franco Piavoli". In Invitto, Giovanni (ed.). Fenomenologia del mito. La narrazione tra cinema, filosofía, psicoanalisi (in Italian). San Cesario di Lecce: Manni. pp. 100–106. ISBN 978-88-8176-854-7.

- Migliorati, Silvia (2013). "Il suono dei melograni. Primi piani di erbe fiori e frutti". Altre Modernità (in Italian) (10): 275–283. doi:10.13130/2035-7680/3358.

- Piavoli, Franco (2011). "Nostos, il ritorno e il mito di Ulisse". In Brunetta, Gian Piero (ed.). Metamorfosi del mito classico nel cinema (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino. pp. 131–137. ISBN 978-88-15-14698-4.

External links

- Official website (in Italian)

- Nostos: The Return at IMDb