Norfolk, Virginia, Bicentennial half dollar

The Norfolk, Virginia, Bicentennial half dollar is a half dollar commemorative coin struck by the United States Bureau of the Mint in 1937, though it bears the date 1936. The coin commemorates the 200th anniversary of Norfolk being designated as a royal borough, and the 100th anniversary of it becoming a city. It was designed by spouses William Marks Simpson and Marjory Emory Simpson.

United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1937 (coins bear the date 1936) |

| Mintage | 25,000 with 13 pieces for the Assay Commission (8,077 melted) |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at the Philadelphia Mint without mint mark |

| Obverse | |

| |

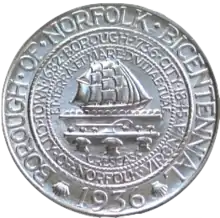

| Design | City seal of Norfolk, Virginia |

| Designer | William Marks Simpson and Marjory Emory Simpson |

| Design date | 1937 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Norfolk's ceremonial mace |

| Designer | William Marks Simpson and Marjory Emory Simpson |

| Design date | 1937 |

Virginia Senator Carter Glass sought legislation for a Norfolk half dollar, but the bill was amended in committee to provide for commemorative medals instead. Unaware of the change, Glass and the bill's sponsor in the House of Representatives, Absalom W. Robertson, shepherded the legislation through Congress. Local authorities in Norfolk did not want medals, and sought an amendment, which passed Congress in June 1937.

The legislation required that all coins be dated 1936; thus, there are five dates on the half dollar, none of which are the date of coining, 1937. By that time, the anniversaries had passed, and sales were poorer than hoped; almost a third of the mintage was returned for melting. The Norfolk half dollar is the only U.S. coin to depict the British crown, shown on the city's ceremonial mace, found on the reverse ("tails" side) of the coin.

Background

Much of the area now comprising the city of Norfolk, Virginia, was granted by Charles I of England in 1636 to Adam Thoroughgood, a former indentured servant who had risen to become a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. Thoroughgood recruited 105 people to live on the land, and named the area for his birthplace, the county of Norfolk in England. Some land was granted to the Willoughby family; this eventually became Norfolk's downtown. In 1736, Norfolk was granted a charter as a royal borough by George II,[1] and the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie presented Norfolk with a ceremonial mace in 1753, making Norfolk the only American city to have a mace from colonial times. Despite being nearly destroyed during the American Revolutionary War, Norfolk was almost as large a port as New York City by 1790, but its importance declined in the 19th century. It remains home to a major naval base.[2]

In the 1930s, commemorative coins were not sold by the government—Congress, in authorizing legislation, usually designated an organization which had the exclusive right to purchase them at face value and vend them to the public at a premium.[3] In the case of the Norfolk half dollar, the responsible group was the Norfolk Advertising Board, Inc., affiliated with the Norfolk Chamber of Commerce.[4]

Legislation

Virginia Senator Carter Glass introduced a bill for a Norfolk Bicentennial half dollar on May 20, 1936; it was referred to the Committee on Banking and Commerce.[5] The bill was reported back to the Senate by Alva Adams of Colorado on June 20. The committee recommended in the report that a medal, not a coin, be issued. They attached a 1935 letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt complaining that commemorative coins of a purely local nature were being authorized by Congress, and recommending that commemorative medals be issued instead.[6]

Franklin E. Turin, August 5, 1936[7]

June 20, 1936, the final day of the session, was an exceptionally busy day in Congress.[7][8] After Adams reported the bill back to the Senate,[9] Glass attempted to have it considered by that body, but initially Joseph Guffey of Pennsylvania objected, demanding the regular order.[10] Later that day, Glass advised the Senate that Guffey had stated he would not further object, and again asked to have the bill considered. This time it passed without objection or debate, and the title was changed to reflect that medals were to be struck rather than coins.[11]

The bill was considered by the House of Representatives later the same day. Absalom W. Robertson of Virginia moved that the House pass it, stating that the bill authorized medals, but when questioned by Robert F. Rich of Pennsylvania, stated that the bill was for "silver coins".[12] The House passed the bill without amendment or debate,[12] and it was signed into law by President Roosevelt on the 28th.[13] Such medals would have had no market, as collectors of the day preferred legal tender coins, which is what the promoters of the bill wanted, and so no medals were struck.[14] It was at first hoped that the initial bill might be used to authorize coins; when this proved not to be the case, the head of the Norfolk Advertising Board, Franklin E. Turin, was interviewed in the Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch on August 5, and "ripped away the veil of secrecy that has shrouded negotiations and called a spade a spade".[7] Turin blamed Roosevelt for the mix-up, and stated that Senator Glass had said he had not realized the bill had been changed, nor had Representative Robertson.[7] Senator Glass promised another attempt.[14]

Glass reintroduced the bill, this time numbered as S. 4, on January 6, 1937.[15] It was reported back to the Senate on the 16th by Adams with an amendment containing language usual to commemorative coin bills, that the federal government would not be responsible for the expenses of preparing the dies for the coinage.[16] The Senate passed it without objection on January 19.[17] The bill was transmitted to the House, where it was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures.[15] That committee on May 26 reported the bill back, recommending that it pass after being amended, including increasing the authorized mintage from 20,000 to 25,000. The report drew attention to the "unfortunate error" of the previous year, and "that in making this favorable report it is merely helping to correct this oversight".[8] The House passed the amended bill on June 21 without discussion or dissent.[18] As the two houses had not passed the same version, the bill returned to the Senate, where on June 22, on Glass's motion, that body agreed to the House's amendments.[19] Roosevelt signed the bill, authorizing 25,000 half dollars, on the 28th.[16]

Preparation

Expecting a coin to be authorized rather than a medal, the Norfolk Advertising Board hired husband and wife William Marks Simpson and Marjory Emory Simpson to design the half dollar, and on September 26, 1936, William Simpson submitted prints of his design to the Commission of Fine Arts.[20][21] The Fine Arts Commission was charged by a 1921 executive order by President Warren G. Harding with rendering advisory opinions on public artworks, including coins.[22] The designs were referred to the sculptor member of the commission, Lee Lawrie. In general, Lawrie was enthusiastic, but had some suggestions. One was to shorten the mace, which almost touched the letter "O" in DOLLAR on the original models. He also advised that further attention should be given to the lettering. The commission chairman, Charles Moore, wrote to William Simpson on September 29, informing him of this, and adding his own congratulations on the design. No formal approval was given at that time, as the coin had not been authorized.[23]

After the coin bill passed Congress in June 1937, the Simpsons modified the design slightly, with the tip of the mace now between the words HALF and DOLLAR, and minor changes being made to the obverse. Photographs of the revised models were sent to the Fine Arts Commission on August 10, 1937; the designs were approved on August 14.[24]

Design

The obverse depicts the city seal of Norfolk. A sailing ship is shown, sailing on stylized waves; below is a plow and three sheaves of wheat. Underneath that is the Latin word CRESCAS, translated as "may you prosper". Above the ship is ET TERRA ET MARE DIVITIAE, meaning "both land and sea are your riches". The inscriptions trace the progress of Norfolk from borough to city, and include the date 1936, as required by the legislation, though the coin was not struck until 1937. The reverse shows Norfolk's mace, with the date of the land grant, 1636, divided by it and flanked by sprigs of dogwood. That date is explained by the words NORFOLK VIRGINIA LAND GRANT. The name of the country, the denomination and the inscriptions required by law are also on the reverse,[25][26] as are the designers' initials, rendered as WM MES.[13] There are five dates on the coin, none of which is the year of minting, 1937.[27]

Q. David Bowers described the obverse as "the most cluttered commemorative design ever produced".[25] Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on U.S. commemorative coins and medals, called the Norfolk piece "a low point in commemorative design".[28] His view was not entirely negative, saying that "skill in spacing the letters, in casting the surfaces, and in modeling the high relief saves much of the composition. Still, the commemoration of Norfolk's anniversaries is a document of epigraphy rather than figural art."[28] Vermeule noted that the coin had been designed by a married couple, and that "the coin gives ample evidence that two heads need not be better than one."[28]

Production and distribution

In September 1937, the Philadelphia Mint struck 25,000 Norfolk half dollars, plus 13 extra that would be held for inspection and testing at the 1938 meeting of the annual Assay Commission. They were placed on sale at $1.50 each, with an initial limit of 20 per purchaser.[29] This limit was later dropped to allow bulk sales to dealers. There was controversy over the half dollar bearing the British Crown as part of the mace—some said the crown had no place on an American coin—and over the fact that the anniversary had passed in 1936. This Turin addressed in advertisements, stating that the crown only appeared as part of the historic mace, and that the city would have issued the coin in 1936 but for the mix-up. Sales were slower than hoped, and Turin promoted the coin through 1938 with mass mailings to coin collectors. Despite this, 5,000 coins were returned to the Philadelphia Mint for redemption and melting in 1938, and 3,077 more at a later date. Several thousand had been sold in bulk to dealers, and wholesale quantities were available on the coin market for years afterward.[30]

The Norfolk half dollar sold at retail for about $1.50 in 1940, in uncirculated condition. It thereafter increased in value, selling for about $18 by 1955, and $170 by 1975.[31] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2018, lists the coin for between $310 and $380, depending on condition.[27] An exceptional specimen sold at auction for $2,760 in 2008.[32]

References

- Flynn, p. 134.

- Slabaugh, p. 141.

- Slabaugh, pp. 3–5.

- Flynn, p. 357.

- "Norfolk, Virginia Anniversary Commemorative Medals". Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2018 – via ProQuest.

- "Authorize Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces in Commemoration of Three-Hundredth Anniversary of Original Norfolk, Va., Land Grant and Two-Hundredth Anniversary of Establishment of that City as a Borough". United States Senate. June 20, 1936. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "Will it Be a Coin or Medal?". The Numismatist: 710. September 1936.

- "Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces in Commemoration of the Norfolk, Va., Land Grant and the Founding of the City of Norfolk, Virginia". United States House of Representatives. May 26, 1937. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, p. 10345 (June 20, 1936)

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, p. 10504 (June 20, 1936)

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, p. 10509 (June 20, 1936)

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, p. 10680 (June 20, 1936)

- Swiatek & Breen, p. 173.

- Bowers, p. 173.

- "Norfolk, Virginia Anniversary Commemorative Coin Act". Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2018 – via ProQuest.

- "To Authorize the Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces in Commemoration of the Three-Hundredth Anniversary of the Original Norfolk (Virginia) Land Grant and the Two-Hundredth Anniversary of the Establishment of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, as a Borough" (PDF). United States Senate. June 28, 1937. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2019.

- 1937 Congressional Record, Vol. 83, p. 298 (January 19, 1937)

- 1937 Congressional Record, Vol. 83, p. 6060 (June 21, 1937)

- 1937 Congressional Record, Vol. 83, p. 6116 (June 22, 1937)

- Flynn, p. 133.

- Taxay, p. 242.

- Taxay, pp. v–vi.

- Taxay, pp. 242–244.

- Taxay, pp. 243–244.

- Bowers, p. 380.

- Swiatek, pp. 357–358.

- Yeoman, p. 1091.

- Vermeule, p. 202.

- Swiatek & Breen, p. 174.

- Bowers, pp. 380–382.

- Bowers, p. 383.

- Flynn, p. 135.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins 2014 (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.