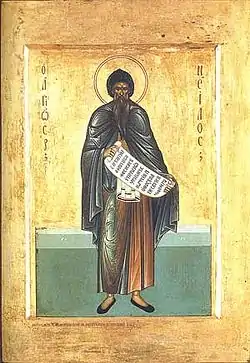

Nilus of Sinai

Saint Nilus the Elder, of Sinai (also known as Neilos, Nilus of Sinai, Nilus of Ancyra; died November 12, 430), was one of the many disciples and stalwart defenders of St. John Chrysostom.

Saint Nilus of Sinai | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | November 12, 430 AD |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church, Roman Catholic Church, Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Feast | 12 November (Catholic and Eastern Orthodox calendars) |

Life

We know him first as a layman, married, with two sons. At this time he was an officer at the Court of Constantinople, and is said to have been one of the Praetorian Prefects, who, according to Diocletian and Constantine's arrangement, were the chief functionaries and heads of all other governors for the four main divisions of the empire. Their authority, however, had already begun to decline by the end of the 4th century.

While St. John Chrysostom was patriarch, before his first exile (398-403), he directed Nilus in the study of Scripture and in works of piety.[1] About the year 390[2] or perhaps 404,[3] Nilus left his wife and one son and took the other, Theodulos, with him to Mount Sinai to be a monk. They lived here till about the year 410[4] when the Saracens, invading the monastery, took Theodulos prisoner. The Saracens intended to sacrifice him to their gods, but eventually sold him as a slave, so that he came into the possession of the Bishop of Elusa in Palestine. The Bishop received Theodulos among his clergy and made him door-keeper of the church. Meanwhile, Nilus, having left his monastery to find his son, at last met him at Elusa. The bishop then ordained them both priests and allowed them to return to Sinai. The mother and the other son had also embraced the religious life in Egypt. St. Nilus was certainly alive till the year 430. It is uncertain how soon after that he died. Some writers believe him to have lived till 451.[5] The Byzantine Menology for his feast (12 November) supposes this. On the other hand, none of his works mentions the First Council of Ephesus (431) and he seems to know only the beginning of the Nestorian troubles; so we have no evidence of his life later than about 430.

From his monastery at Sinai Nilus was a well known person throughout the Eastern Church; by his writings and correspondence he played an important part in the history of his time. He was known as a theologian, Biblical scholar and ascetic writer, so people of all kinds, from the emperor down, wrote to consult him. His numerous works, including a multitude of letters, consist of denunciations of heresy, paganism, abuses of discipline and crimes, of rules and principles of asceticism, especially maxims about the religious life. He warns and threatens people in high places, abbots and bishops, governors and princes, even the emperor himself, without fear. He kept up a correspondence with Gainas, a leader of the Goths, endeavouring to convert him from Arianism;[6] he denounced vigorously the persecution of St. John Chrysostom both to the Emperor Arcadius[7] and to his courtiers.[8]

Nilus must be counted as one of the leading ascetic writers of the 5th century. His feast is kept on 12 November in the Eastern Orthodox calendar; he is commemorated also in the Roman martyrology on the same date. The Armenian Church remembers him, with other Egyptian fathers, on the Thursday after the third Sunday of their Advent.[9]

Prophecy of St. Nilus

The Prophecy of St. Nilus is an apocryphal work of uncertain origin (thus often referred to as the Prophecy of Pseudo-Nilus) predicting the apocalypse to occur in the 19th or 20th century (depending on the version of the text). The creation of this work is very dubious[10] whose date of creation is unverified.[11] With the advent of the Internet, the work has taken on the status of urban legend. One source has cited the Bibliotheca Sanctorum, volume IX, page 1008 as a possible origin of the text.[12][13]

These prophecies likely originated from the Russian Orthodox St. Nilus, called Nilus of Sora, but has been wrongly attributed to Nilus of Sinai. Between the years 1813 and 1819, a certain monk named Theophanes, also known as the “Prisoner”, was troubled by a demon due to his many sins, and he also suffered from a hernia. In despair over his condition he planned to leave the Holy Mountain until one day St. Nilus appeared to him. St. Nilus showed him an abandoned hut and instructed him to settle there, promising to provide for his needs. Theophanes obeyed, although at first he did not know it was St. Nilus - only later did the Saint reveal himself.

St. Nilus appeared to him several times, healed him, and taught him about spiritual warfare. Cleansed of his passions and sins through proper ascetic struggle, St. Nilus ordered him to take the Great Schema and bear the name Ekhmalotos (Prisoner) as a sign that now he was a captive of St. Nilus for healing him of demonic possession and vice.

St. Nilus told Monk Ekhmalotos he wanted a path made to his cave so that monks could go there to pray. He also wanted the Liturgy to be served in the cave church he himself had built.

When the Fathers heard this, they wished to build a new church in honor of St. Nilus. As they were digging the foundation, they found the saint’s grave. From his relics an ineffable fragrance came forth. This took place on May 7, 1815. Then the monks informed the Fathers of the Great Lavra of their discovery. They came and transferred the relics to the Lavra, leaving only a portion of the saint’s jaw at the cave to be venerated by those who came there.

At the request of certain monks from Kafsokalyvia, Monk Ekhmalotos wrote down the appearances of the Saint, and later St. Nilus told him to write down his words in full. Because he was barely literate he dictated the story and prophecies to a Hieromonk Gerasimos from Constantinople, who recorded it word for word.

The entire chronicle of St. Nilus’ teachings and prophecies to the Monk Theophanes between the years 1813 to 1819 fill a six-hundred page book, available in Greek and Russian. A monk by the name of Iakovos from Iveron Monastery copied this entire text and published it in 1906. It includes prophecies of the invasion of the Holy Mountain during the Greek Revolution, the 1821 Revolution itself, the end of monasticism on the Holy Mountain, and the struggles of the monks of the last times.

So this is the likely source of the prophecies of St. Nilus.[14]

Works

The writings of St. Nilus of Sinai were first edited by Petrus Possinus (Paris, 1639); in 1673 Suarez published a supplement at Rome; his letters were collected by Possinus (Paris, 1657), a larger collection was made by Leo Allatius (Rome, 1668). All these editions are used in Patrologia Graeca, vol. 79. The works are divided by Fessler-Jungmann into four classes:

- Works about virtues and vices in general: — "Peristeria" (P. G., 79, 811-968), a treatise in three parts addressed to a monk Agathios; "On Prayer" (peri proseuches, ib., 1165–1200); "Of the eight spirits of wickedness" (peri ton th'pneumaton tes ponerias, ib., 1145–64); "Of the vice opposed to virtues" (peri tes antizygous ton areton kakias, ib., 1140–44); "Of various bad thoughts" (peri diapsoron poneron logismon, ib., 1200–1234); "On the word of the Gospel of Luke", 22:36 (ib., 1263–1280).

- "Works about the monastic life": — Concerning the slaughter of monks on Mount Sinai, in seven parts, telling the story of the author's life at Sinai, the invasion of the Saracens, captivity of his son, etc. (ib., 590-694); Concerning Albianos, a Nitrian monk whose life is held up as an example (ib., 695-712); "Of Asceticism" (Logos asketikos, about the monastic ideal, ib., 719-810); "Of voluntary poverty" (peri aktemosynes, ib., 968-1060); "Of the superiority of monks" (ib., 1061–1094); "To Eulogios the monk" (ib., 1093–1140).

- "Admonitions" (Gnomai) or "Chapters" (kephalaia), about 200 precepts drawn up in short maxims (ib., 1239–62). These are probably made by his disciples from his discourses.

- "Letters": — Possinus published 355, Allatius 1061 letters, divided into four books (P. G., 79, 81-585). Many are not complete, several overlap, or are not really letters but excerpts from Nilus' works; some are spurious. Fessler-Jungmann divides them into classes, as dogmatic, exegetical, moral, and ascetic.

Certain works wrongly attributed to Nilus are named in Fessler-Jungmann, pp. 125–6.

Literature

- Nikephoros Kallistos, Hist. Eccl., XIV, xliv

- Leo Allatius, Diatriba de Nilis et eorum scriptis in his edition of the letters (Rome, 1668)

- Tillemont, Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire ecclésiastique, XIV (Paris, 1693–1713), 189-218;

- Fabricius-Harles, Bibliotheca graeca, X (Hamburg, 1790–1809), 3-17;

- Ceillier, Histoire générale des auteurs sacrés, XIII (Paris, 1729–1763), iii;

- Josef Fessler-Bernard Jungmann, Institutiones Patrologiœ, II (Innsbruck, 1896), ii, 108-128.

Notes

- Nikephoros Kallistos, hist. Eccl., 14, 53, 54.

- Tillemont, Mémoires, 14, 190-91.

- Leo Allatius, De Nilis, 11-14.

- Tillemont, ib., p. 405.

- Leo Allatius, op. cit., 8-14.

- Book I of his letters, nos. 70, 79, 114, 115, 116, 205, 206, 286.

- ib., II, 265; III, 279.

- I, 309; III, 199.

- Nilles, Kalendarium Manuale, Innsbruck, 1897, II, 624.

- http://southern-orthodoxy.blogspot.com/2005/01/spooky-doxy.html

- http://www.traditioninaction.org/Questions/B260_MoreNilus.html

- Prophecy of St. Nilus

- Biblioteca Sanctorum, volume IX, page 1008

- http://www.roacamerica.org/ann-historical_instances_righteous_hierarchs_unjustly_condemned_by_synods.shtml

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nilus of Sinai |

- Saints.SQPN: Nilus the Elder

- Catholic Online: Nilus the Elder

- Venerable Nilus the Faster of Sinai in Orthodox Church in America

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Missing or empty |title= (help)