Nikifor Grigoriev

Nikifor (Nikolay) Aleksandrovich Grigoriev (Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Григо́рьев; c. 1885 – July 27, 1919), born Nychypir Servetnyk (Ukrainian: Ничипір Серветник) in a small village of Zastavlia (now in the Nova Ushytsia Raion, Ukraine), was a paramilitary leader noted for numerous switching of sides during the Civil War in Ukraine. He was commonly known as "Otaman Grigoriev", as "Matviy Hryhoriyiv", "Matvey Grigoriev", or "Mykola Grigoriev".

Nikifor Grigoriev | |

|---|---|

Servetnyk in 1919 | |

| Nickname(s) | Otaman Grigoriev |

| Born | 1885 near Dunaivtsi, Podolia Governorate, Russian Empire (now Ukraine) |

| Died | July 27, 1919 (aged 33–34) village of Sentove, Ukraine |

| Allegiance | Hetman State of Ukraine, UNR, Ukrainian left SRs (borotbisty), Makhno. |

| Years of service | 1904–1919 |

| Rank | Staff Captain (Russian Army) Otaman (Ukrainian Army) Division Commander (Red Army) |

| Commands held | Ukrainian Kherson Division 1st Trans-Dnipro Brigade (Ukraine) 1st Trans-Dnepr Brigade (Red Army) 6th Ukrainian Rifle Division (Red Army) |

| Battles/wars | Russo-Japanese War World War I Ukrainian Civil War Southern Russia Intervention Odessa Operation (1919) Grigoriev Uprising |

| Awards | Cross of St. George |

He is sometimes misrepresented as the Otaman of the "Green Army". His association with the term "Green Army" is due to collaboration with the army of Otaman Zeleny (Green in Russian and Ukrainian) which fought against the UNR Directory, Bolsheviks, and Denikin's Army. Although he cooperated with Zeleny, this was marginal.

Biography

The Otaman or "warlord" was born Nychypir Servetnyk in a small village of Zastavlia (still stands today) of Novo-Ushytsia uyezd in Podolia Governorate. Servetnyk served in the cavalry of the Russian Imperial Army in the region of Kherson and participated in Russo-Japanese War in the Russian Far East serving in the Trans-Baikal Host. After his discharge he served as a gendarme in the town of Proskuriv, Podolia Governorate.

Servetnyk volunteered to the army with the outbreak of the First World War and was enlisted as a Praporshchik (see Rank structure) to the 56th Zhytomyr Infantry Regiment in 1914. In course of war, he was awarded the Cross of St. George for bravery. Servetnyk eventually rose to the rank of staff captain (Russian: Штабс-капитан) in the 58th Prague Infantry Regiment (1917) and changed his surname to Grigoriev. During this period he became a member of Eser (Socialist-Revolutionary) Party. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 (February Revolution and October Revolution), he supported the socialist-oriented Ukrainian Central Rada of the UNR Ukrainian National Republic. He served in the reorganized National Army of Ukraine and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Russian Civil War period

In April 1918, he took part in the conservative coup d'etat led by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky which earned him the rank of colonel. In the summer of that year, he revolted against the Hetman State and created his own insurgent army. He joined another revolt in November that year which was organized by the Dyrektoria. During the Russian Civil War in December Grigoriev participated in the military campaign against the Russian forces of the South. During that campaign he took Mykolaiv, Kherson, Ochakiv, Oleshky. Before capturing Mykolaiv he overran the forces of already defeated Hetmanate of 545 soldiers. He occupied Mykolaiv on December 13 and appointed himself the city commissioner struggling against the city council. Grigoriev was appointed a commander of the Ukrainian Kherson Division of the Southern group of General Hrekov until January 29, 1919, later the 1st Trans-Dnipro Rifllemen Brigade (~6,000 men) of the 3rd Trans-Dnipro Riflemen Division.

He was later forced out of those cities by the Entente forces (Greek and French) (see Southern Russia Intervention). During this time the general Hrekov participated in the negotiations with The Entente forces to ally against the Bolsheviks. Grigoriev did not approve that and was especially upset when Vynnychenko was forced out of the office leading Petliura to head the Directory Committee later on February 13. On January 29, 1919, Grigoriev sent a letter to the headquarters of the Zaporizhia Corps in Kremenchuk (a week after the arrest of the UNR Col. Petro Bolbochan):

In Kiev gathered the Otamanate, the Austrian Fendryky Reserves, country-side teachers, and all kinds of careerists and adventurists who pose themselves for statesmen and big diplomats. They are not the professionals and definitely out of place, I do not believe them and move on to the Bolsheviks as after the arrest of Colonel Bolbochan I do not believe in the good of our Homeland.

On January 25, 1919, Petliura ordered him and Otaman Hulai-Hulenko to join the South-Eastern group against the Armed Forces of South Russia near Alexandrovsk and Pavlohrad. Grigoriev decided to ignore that order. He had no intentions to fight against the White forces as well as the forces of Makhno who operated in the area and were in opposition to the Directorate. Since that time he systematically ignored all the orders that were coming from the Headquarters of the Ukrainian Army. A similar situation was taken place throughout the Ukrainian Armed Forces at that time. On January 30, Grigoriev sent a representative to the Yelizavetgrad revkom claiming to be the Chairman of the Soviet Emissaries. He also sent a telegram to the revkom of Alexandrovsk with an approval for the actions of the Soviet Bolshevik Left-SR government of the Ukrainian SSR.

At the beginning of February 1919, Grigoriev attacked the UNR Katerynoslav Kosh of Colonel Kotyk whom he captured as well. Later he sent a telegram to Red Kharkiv informing that he caught the cat (implying to Colonel Kotyk). The Ukrainian Command immediately announced him outlawed, warranting every citizen of the Republic to kill the deserter. On February 2 the Ukrainian left SR (Borotbist) Vasyl Ellan-Blakytny arrived at Znamenka to organize the Soviet Ukrainian National government with the help of Grigoriev, but later he telegraphed back to Moscow not to hurry with the coalition with Otaman Grigoriev due to possible treachery. Grigoriev, nonetheless, continued his attacks and effectively stormed Kryvyi Rih and Yelizavetgrad causing UNR forces to withdraw out of Central Ukraine to Podolia.

Allying with the Bolsheviks

After the withdrawal of UNR forces from Kiev, Otaman Grigoriev continued his negotiations with the Bolsheviks on February 18, 1919. Grigoriev together with his brigade became now part of the Red Army 1st Trans-Dnieper Riflemen Division (later expanded to the 6th Ukrainian Rifle Division), while Nestor Makhno led his troops as another brigade of that division and Pavel Dybenko who commanded the division was in charge of another brigade. He was still closely connected with the Socialist-Revolutionaries who had great influence over the rural population of the country. During that time, he attacked the Askania-Nova preserve and started food requisitioning in the name of Revolution. The head of government of Soviet Ukraine Christian Rakovsky sent Grigoriev a note of protest in that regard. In a short time, however, April 1919 the preserve would be nationalized.

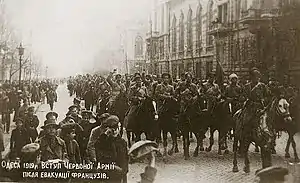

In March 1919 he advanced with his Army against the Allied Intervention force. He first took Kherson, later Grigoriev managed to take Mykolaiv and after a two-weeks battle on April 8, he occupied Odessa forcing the Greek-French forces to withdraw. At first, he was appointed the commandant of the city, but Bolsheviks subsequently protested the plunder of Odessa by Grigoriev's troops.

As the Red Army officer[1][2] Grigoriev was responsible for pogroms in 40 communities and the deaths of about 6,000 Jews in the summer of 1919.[3]

Rebellion and alliance with Makhno

In May, Grigoriev deserted the Red Army, opposed to Bolshevik requisitioning policies and after being ordered to assault into the Romanian territories in order to provide military support for Soviet Hungary and with his units captured the city of Yelisavetgrad (today Kropyvnytskyi).

In his rebellion against the Red Army, called the Grigoriev uprising, he was supported by most southern-Ukrainian peasants who were outraged by the Bolshevik policy of "war communism" (including rural confiscation of food), and were also hostile to the White movement that was backed by land-owners. The anti-Bolshevik uprising started on 8 May 1919, when Grigoriev issued a proclamation "To the Ukrainian People" (До Українського народу), in which he called upon the Ukrainian people to rise against the "Communist imposters", singling out the "Jewish commissars"[4] and the Cheka. In only a few weeks, Grigoriev's troops perpetrated 148 pogroms, the deadliest of which resulted in the massacre of upwards of 1,000 Jewish people in Yelisavetgrad, from 15 to 17 May 1919.[4]

In July 1919, after suffering heavy losses against the Red Army, Grigoriev escaped to the areas controlled by Nestor Makhno and offered to join the forces against "the Reds and the Whites". His proposition was accepted.

Makhno did not trust Grigoriev. After 3 weeks of common actions against Bolshevik forces, Grigoriev openly disagreed with Makhno during negotiations at Sentovo on July 27, 1919 (today it is a village of Rodynkivka, Oleksandriia Raion, Kirovohrad Oblast). Grigoriev had been in contact with Denikin's emissaries and was planning to join the White coalition. This was unacceptable to Makhno — he held a particular hatred of all monarchists and aristocrats since the time of his imprisonment. According to Peter Arshinov, Makhno and the staff decided to execute Grigoriev. Chubenko, a member of Makhno's staff, accused Grigoriev of collaborating with Denikin (According to Arshinov, Denikin's emissaries were captured and executed) and of inciting the pogroms.[5] There are several accounts that give different circumstances of Grigoriev's death. Grigoriev threatened Chubenko and Makhno, drew his gun, and was shot and killed. The accounts of the event differ, and ascribe the final shot either to Chubenko, Karetnik or Makhno.[5][6][7]

Awards

- Cross of St. George for bravery as well as Bolshevik orders

- Order of the Red Banner[8]

Notes

- Timkov, O. Otaman Grigoryev: Truth and Myth.

- Timkov, O. Otaman Grigoryev: Truth and Myth.

- Encyclopedia Judaica vol. 13 pp. 699-700

- Werth, Nicolas (2019). "Chap. 5: 1918-1921. Les pogroms des guerres civiles russes". Le cimetière de l'espérance. Essais sur l'histoire de l'Union soviétique (1914-1991) [Cemetery of Hope. Essays on the History of the Soviet Union (1914–1991)]. Collection Tempus (in French). Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-07879-9.

- Alexandre Skirda, Nestor Makhno: Anarchy's Cossack, p 125.

- Nestor Makhno, "The Makhnovshchina and Anti-Semitism," Dyelo Truda, No.30-31, November-December 1927, pp.15-18

- Peter Arshinov "History of the Makhnovist Movement 1918-1921" Ch. 7

- Formation of the Soviet statehood in Ukraine.

External links

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine article

- Ataman of Pogroms Grigoriev (in Russian)

- Bio in Russian (in Russian)

- Universal of Grigoriev

References

- П. Аршинов. История махновского движения.

- Нестор Махно. Воспоминания.

- Дневник Г. А. Кузьменко (Издательство Терра, 1996 г., 496 рр. ISBN 5-300-00585-1