New Georgia counterattack

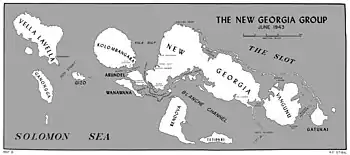

The New Georgia counterattack was a counterattack on 17–18 July 1943 by mainly Imperial Japanese Army troops against United States Army forces during the New Georgia campaign in the Solomon Islands. The U.S. and its allies were attempting to capture an airfield constructed by the Japanese at Munda Point on New Georgia with which to support further advances towards the main Japanese base around Rabaul as part of Operation Cartwheel.

| New Georgia counterattack | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

Injured U.S. Army soldiers are evacuated through the jungle on New Georgia on 12 July 1943 a few days before the Japanese counterattack. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3 infantry regiments | 2 infantry regiments (less one battalion) | ||||||

The Japanese attack saw one infantry regiment from the Southeast Detachment carry out a frontal assault against the center and left of the U.S. front line, while another carried out a flanking attack on their left aimed at enveloping the U.S. forces and cutting them off from their supply line. While the frontal assault was checked, the flanking attack succeeded in breaking into the rear of the U.S. beachhead. Many casualties were inflicted among the logistics, support and medical troops in the area, and the 43rd Infantry Division's command post came under attack before heavy defensive artillery fire and local defensive fighting forced the Japanese attackers back. Ultimately, the Japanese attack was unsuccessful, having been badly coordinated, and after a brief lull in the fighting, the U.S. forces launched a two-week long corps-level offensive that captured the airfield on 4–5 August 1943.

Background

Strategic situation

In the wake of the Guadalcanal campaign, concluded in early 1943, the Allies formulated plans to advance through the Central Solomons towards Bougainville, in conjunction with further operations in New Guinea. These plans formed part of the effort to reduce the main Japanese base around Rabaul, which was designated Operation Cartwheel. Capture of the airfield at Munda would facilitate further assaults on Vila, Kolombangara and Bougainville.[1][2] For the Japanese, New Georgia formed a key part of the defenses protecting the southern approaches to Rabaul. Accordingly, they sought to defend the area strongly, and moved reinforcements by barge along the Shortlands–Vila–Munda supply line.[3][4]

The Allied campaign plan for securing New Georgia, designated Operation Toenails by U.S. planners, involved several landings by elements of Major General Oscar Griswold's XIV Corps to secure staging areas and an airfield in the southern part of New Georgia at Wickham Anchorage, Viru Harbor and Rendova. Once captured, these would then be garrisoned to support the movement of troops and supplies from Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands to Rendova, which would be built up as base for further operations in New Georgia focused on securing the airfield at Munda.[1][2]

The Americans landed reconnaissance elements around Zanana on New Georgia on 30 June; this marked the start of the New Georgia campaign. These were followed by main force elements from Major General John H. Hester's 43rd Infantry Division on 2 July 1943, crossing from Rendova where they had landed on 30 June. After establishing a beachhead, the American troops made limited gains in their drive toward Munda Point and advanced slowly against strong opposition.[5] From the outset, the Japanese forces around Zanana, consisting largely of troops from the 229th Infantry Regiment and 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force, fought to delay the U.S. advance while reinforcements were dispatched.[6] Over the course of several weeks, they delayed the U.S. troops' westward advance on Munda, and defeated an attempt to outflank their defenses.[7][8]

In order to renew the offensive, the U.S corps commander, Griswold, was sent to New Georgia to assess the situation. He reported back to Admiral William Halsey on Noumea that the situation was dire and requested reinforcements in the form of at least another division to break the stalemate.[9] Griswold took over command of the troops in the field from Hester on 15 July and began preparations for a corps-level offensive. The build up would take about 10 days, and amidst this situation, the Japanese began preparations for a counterattack.[10]

Japanese reinforcements

Japanese reinforcements arrived at New Georgia during July. The initial reinforcements comprised approximately 3,000 troops from the 13th and 229th Infantry Regiments, as well as a number of support units. These soldiers were stationed in the Shortland Islands.[11] The first attempt to transport soldiers to New Georgia began on 4 July, when four destroyers departed Buin in Bougainville. The Japanese ships broke off the attempt to land troops when they encountered a U.S. Navy bombardment force off Rice Anchorage in the early hours of 5 July, though they sank the destroyer USS Strong.[11][12]

The Japanese had more success in landing troops the next day. A larger force of destroyers was dispatched, and landed about 1,600 troops and 90 tons of supplies. The Japanese destroyers were intercepted by an American force of cruisers and destroyers, and in the Battle of Kula Gulf, which was fought during the early hours of 6 July, an American cruiser and two Japanese destroyers were sunk.[13] Three Japanese cruisers and four destroyers landed 1,200 soldiers unopposed on Kolombangara on the night of 9/10 July.[14] On the night of 12/13 July, a further 1,200 Japanese soldiers were landed at Vila, though the Imperial Japanese Navy lost a light cruiser and the U.S. Navy a destroyer in the Battle of Kolombangara.[15]

The troops landed at Kolombangara were subsequently moved to New Georgia by barge.[16] Other Japanese units were moved to New Georgia piecemeal on board barges during July.[17] Overall, the units that arrived in the Munda Point area between early and mid-July were the 3rd Battalion of the 229th Infantry Regiment, the 2nd Battalion of the 230th Infantry Regiment, the 13th Infantry Regiment, the 2nd Battalion of the 10th Independent Mountain Regiment and anti-aircraft, anti-tank, engineer and signals units. In addition, the 2nd Battalion of the 45th Infantry Regiment was transferred from Bougainville to Bairoko on the north coast of New Georgia.[18] These reinforcements enabled the Japanese to maintain their strength on New Georgia and prepare a counterattack, despite the American advances.[17]

Opposing forces

Around 30,000 U.S. troops were committed to actions around Munda throughout July and August, while the Japanese allocated around 8,000 troops.[19] The U.S. troops were under the command of Griswold, commander of XIV Corps,[20] and the Japanese force was commanded by Major General Minoru Sasaki of the Southeast Detachment.[21] For the counterattack, Sasaki's main fighting elements totaled around five infantry battalions.[22][23] These were drawn from the 229th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Genjiro Hirata, and the 13th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Tomonari Satoshi.[24] The U.S. troops allocated consisted mainly of three infantry regiments from Hester's 43rd Infantry Division; to reinvigorate the advance on Munda, Griswold had requested reinforcements from the 37th and 25th Infantry Divisions, commanded by Major Generals Robert S. Beightler and J. Lawton Collins respectively. Ultimately, though, these divisions would not complete their movement to the battle area until after the Japanese counterattack.[23][25][26]

Battle

Due to the decision by U.S. commanders to land at Zanana in early July, rather than further west along the coast, the American lines of communication became stretched and vulnerable as the advance towards Munda continued. Meanwhile, the inexperienced American troops were disorganized and suffering from poor morale and bad leadership, having become bogged down by harsh terrain and bad weather, which had quickly turned the jungle tracks into mud.[27] Sasaki launched his counterattack at the moment that the U.S. advance halted to reorganize.[28][21] The objective of the Japanese operation was to destroy the American forces on New Georgia by attacking their exposed flank and rear areas. It was intended that the attack would be coordinated with naval operations to cut off the American troops on New Georgia and air attacks on Allied logistical bases on the island elsewhere.[29]

Sensing an advantage, Sasaki ordered the 13th Infantry Regiment to penetrate the U.S. right flank around the upper reaches of the Barike River and attack their rear elements, while elements of the 229th which were already occupying defensive positions along the front attacked the left flank.[28][30] A total of six companies from two battalions of the 13th Infantry Regiment were committed to this effort, while the regiment's 2nd Battalion remained around Bairoko. These troops began moving from their assembly area in a plantation 5 miles (8.0 km) north of Munda on 14 July.[23]

.jpg.webp)

While Tomonari's troops began their march, those of Hirata's 229th in the center of the line undertook a series of patrols and minor attacks to keep the U.S. forces off balance.[31] Hampered by the terrain just as the U.S. troops had been, it took three days for Tomonari's troops to complete their preliminary move.[32][33] From the Barike, the Japanese began probing the Allied right flank, which was only lightly held by isolated outposts, before moving towards an assembly area for the main assault. Track improvement had not been completed in this area and, as a result, the U.S. outposts could not be reinforced quickly. Sasaki planned for Tomonari's forces to infiltrate this area and sever the supply lines from Zanana while Hirata's 229th Infantry Regiment advanced from Munda to assault the center and right of the U.S. line. In doing so, the Japanese hoped to complete an envelopment of the U.S. regiments holding the front. The element of surprise was lost, however, when U.S. patrols detected the infiltration. In the afternoon of 17 July, elements of the U.S. 43rd Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop unsuccessfully attempted an ambush but were overwhelmed in the attempt.[30][34]

Despite the Japanese commander's intentions to coordinate the efforts of the forces assigned to the counterattack, ultimately this was not achieved as the Japanese force lacked communications equipment. Japanese preparations were also disrupted by U.S. artillery fire around 11:30 on 17 July, which landed on the forward positions of the 229th Infantry Regiment just prior them forming up for the assault in the center of the U.S. line and this ultimately delayed their attack. Artillery and air strikes also broke up an effort by naval troops from the Yokosuka 7th Special Naval Landing Force to launch an amphibious landing behind the Allied front.[34][31] Throughout 17 July, the 229th was kept off balance around the Laiana beachhead by the U.S. 172nd Infantry Regiment with well coordinated close armored support from several Marine Corps tanks, while the U.S. 169th Infantry Regiment carried out a local attack between Reincke Ridge and Kelley Hill with two battalions which kept the Japanese in contact throughout the day.[34][35]

Meanwhile, at around 16:00, the 13th Infantry Regiment reached a mangrove swamp on the bank of the Barike River, where they began to assemble for the attack on the beachhead.[31] The rear area of the U.S. beachhead consisted of many spread out camps and facilities that were mainly occupied by logistics, support and technical troops. Throughout the night of 17–18 July, formed into small section or platoon-sized groups,[36] the Japanese succeeded in infiltrating and attacking several isolated outposts in the American rear areas, which were hastily defended by small groups of support troops. Over several hours, they carried out minor raids against supply dumps and engineer depots, and ambushed medical parties, inflicting many casualties on the American forces. During the confused fighting, the Japanese raiders destroyed vital telephone switch boards in an effort to disrupt communications. Nevertheless, the US forces were able to maintain communications with their supporting artillery battalions through a single telephone and throughout the night the artillery liaison officer called down heavy barrages from offshore batteries in response, some within 150 yards (140 m) of the divisional command post.[28][37]

Although the attack in the rear areas continued throughout the night, the artillery fire prevented the Japanese from being able to concentrate in strength. The beachhead area was also attacked, but a force of 52 Marines from the 9th Defense Battalion commandeered two U.S. Army .30 caliber machine guns and occupied a defensive position on a knoll about 150 yards (140 m) inland, supported by an anti-tank platoon and an ad hoc force of another fifty service troops and artillerymen. From this position, at around 21:00 they ambushed a force of Japanese attackers moving from the command post to set up a mortar, while others manned the unit's antiaircraft guns. The Japanese made four efforts to push through the ambush, but ultimately withdrew, leaving at least 18 of their number dead.[28][38] Other raiders attacked kitchen areas and medical facilities, including casualty clearing stations. At one aid station, several patients fought back, killing four Japanese.[39] In other stations, the medics and doctors attempted to fight off Japanese infantrymen who bayoneted patients in their beds.[36]

In the center of the line, and further to the south, just after midnight on 17–18 July, two battalions (the 2nd and 3rd) from Hirata's 229th Infantry Regiment began a series of attacks against elements of the US 169th Infantry Regiment.[40] After the initial attack against the 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry Regiment around Kelley Hill failed, the second effort began well for the Japanese who were able to skillfully advance close to the line in places to hurl grenades into the US front line. Mortar fire attempted to flush these troops out, and eventually the Japanese effort in the center of the lines was fought to a standstill as the defending troops used the high ground to their advance, calling down accurate artillery barrages down on the attacking troops, of which at least 102 were killed.[37] Two hundred men from the Japanese 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry Regiment, which had been withdrawing from the Segi area following earlier fighting around Viru Harbor, stumbled into the area and also joined in the attack against a company of the U.S. 169th Infantry Regiment.[22] An assault against the 3rd Battalion, 103rd Infantry Regiment, which had been assigned to support the 172nd Infantry Regiment around the beach area, was also beaten back.[40][37]

Griswold urgently requested reinforcements. A battery was dispatched to Zanana from Kokorana and the 148th Infantry Regiment began preparations to move from Rendova at first light.[37] Ultimately, though, the attack on the beachhead petered out and the 13th Infantry Regiment melted into the jungle during the morning of 18 July. They would remain scattered in small numbers, and in the aftermath of the attack continued to harass U.S. troops. Sasaki hoped to be able to mount another effort to go on the offensive, but ultimately this opportunity did not eventuate.[41]

Aftermath

According to the historian Eric Hammel, "the action cost both sides many lives", although exact casualty numbers are not specified.[42] The US Army official historian John Miller Jr. judged that the Japanese 13th Infantry Regiment's attacks "caused a few casualties but accomplished very little, certainly not enough to justify its trip from Kolombangara".[37]

The arrival of U.S. reinforcements began early on 18 July, with elements of the 148th Infantry Regiment landing at Zanana. Having hurriedly embarked at Rendova, they had been told to expect to fight as soon as they landed, but the fighting around the beach had concluded by the time they arrived. They were quickly pushed inland by U.S. commanders to shore up their vulnerable right flank and open the Munda Trail; during this movement the regiment's advanced elements clashed several times with small groups of Japanese infantry. Efforts to relieve the 169th took several days, with minor actions continuing until 20 July, including an ambush around one of the bridges across the Barike.[39] In the coming days both the 145th and 161st Infantry Regiments arrived, and deployed opposite three battalions from the Japanese 229th Infantry, and a company from the 230th.[40]

After the Japanese counterattack was defeated, the U.S. commanders completed preparations for a corps-level offensive to capture Munda, bringing in further reinforcements and supplies. A secondary landing had been undertaken closer to Munda, around Laiana, to shorten supply lines. Medical and logistic support was also improved utilizing the secondary landing beach that had been established around Laiana on 14 July.[27] During the lull that followed, U.S. forces undertook a series of patrols to gather information about Japanese dispositions; a number of minor firefights took place during this time, with only limited casualties.[43] Meanwhile, the Japanese commander, Sasaki, also resolved to renew the offensive. He ordered Tomonari to launch another counterattack on 25 July,[39] aiming an attack on the U.S. right flank around Horseshoe Hill and then rolling up the Allied line east along the Munda Trail. Griswold ordered a renewed offensive on 22 July; this began three days later and nullified the Japanese efforts.[44]

Supported by a strong naval bombardment on Lambeti Plantation, between Munda and Laiana, augmented by shore-based artillery and airstrikes, on 25 July the U.S. attack commenced with two divisions being committed across the front.[45] The 37th Division attacked towards Bibilo Hill while the 43rd Division drove towards Lambeti Plantation and the airfield.[46] After a sustained offensive that lasted two weeks, the Allies eventually captured the airfield in the Battle of Munda Point on 4–5 August. As the Japanese began withdrawing from New Georgia towards Kolombangara, U.S. forces undertook mopping up operations throughout August, during which time they advanced north from Munda to link up with the U.S. Marines and U.S. Army troops that had landed around Bairoko in early July. Bangaa Islet was secured in late August, while Arundel Island was captured later the following month.[47]

Notes

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 73

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 52

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, backcover

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 180

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 92–94 & 120.

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, pp. 98–99

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 106–115

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 177

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 198

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 199

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, p. 98

- O'Hara, The U.S. Navy Against the Axis, pp. 170–173

- O'Hara, The U.S. Navy Against the Axis, pp. 173–180

- O'Hara, The U.S. Navy Against the Axis, p. 180

- O'Hara, The U.S. Navy Against the Axis, pp. 180–186

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, p. 100

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, p. 99

- Rottman, Japanese Army in World War II, p. 67

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 93

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 127

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, pp. 32 & 54

- Hammel, Munda Trail, pp. 146–147

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, p. 54

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, pp. 81–83

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 137 & 144

- Hammel, Munda Trail, p. 128

- Nalty, War in the Pacific: Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay, p. 121

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, pp. 104–105

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, pp. 99, 104

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 135–136

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 83

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, pp. 82–83

- Shaw and Kane, Isolation of Rabaul p. 100

- Shaw & Kane Isolation of Rabaul, p. 104

- Hammel, Munda Trail, pp. 122 & 138

- Hammel, Munda Trail, p. 141

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 136

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, pp. 83–84

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 202

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, p. 55

- Shaw & Kane Isolation of Rabaul, p. 106

- Hammel, Munda Point, p. 148

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, pp. 106–107

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 143–146

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 203

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 143–144

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 135–136, 163–164, 167–172, 184

References

- Hammel, Eric M. (1999). Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign, June-August 1943. Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-935553-38-X.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 494892065.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, vol. 6 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Castle Books. OCLC 248349913.

- Nalty, Bernard C. (1999). War in the Pacific: Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-80613-199-3.

- O'Hara, Vincent (2007). The U.S. Navy Against the Axis: Surface Combat, 1941–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-185-2.

- Rentz, John (1952). "Marines in the Central Solomons". Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 566041659.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Duncan Anderson (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. OCLC 464447997.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47282-450-9.

Further reading

- Altobello, Brian (2000). Into the Shadows Furious. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-717-6.

- Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate. "Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Day, Ronnie (2016). New Georgia: The Second Battle for the Solomons. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253018779.

- Feldt, Eric Augustus (1991) [1946]. The Coastwatchers. Victoria, Australia: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014926-0.

- Hayashi, Saburo (1959). Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Marine Corps. Association. ASIN B000ID3YRK.

- Hoffman, Jon T. (1995). "New Georgia" (brochure). From Making to Bougainville: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Historical Center. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- Horton, D. C. (1970). Fire Over the Islands. ISBN 0-589-07089-4.

- Lofgren, Stephen J. Northern Solomons. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. p. 36. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- Lord, Walter (2006) [1977]. Lonely Vigil; Coastwatchers of the Solomons. New York: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-466-3.

- McGee, William L. (2002). The Solomons Campaigns, 1942-1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville--Pacific War Turning Point, Volume 2 (Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII). BMC Publications. ISBN 0-9701678-7-3.

- Melson, Charles D. (1993). "Up the Slot: Marines in the Central Solomons". World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 36. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1993). "Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Radike, Floyd W. (2003). Across the Dark Islands: The War in the Pacific. ISBN 0-89141-774-5.

- Rhoades, F. A. (1982). A Diary of a Coastwatcher in the Solomons. Fredericksburg, Texas: Admiral Nimitz Foundation.

- United States Army Center of Military History. "Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – Part I". Reports of General MacArthur. Retrieved 8 December 2006. – Translation of the official record by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaux detailing the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy's participation in the Southwest Pacific area of the Pacific War.