Natural farming

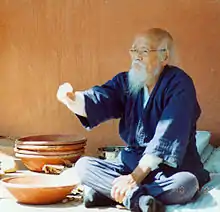

Natural farming is an ecological farming approach established by Masanobu Fukuoka (1913–2008), a Japanese farmer and philosopher, introduced in his 1975 book The One-Straw Revolution. Fukuoka described his way of farming as 自然農法 (shizen nōhō) in Japanese.[1] It is also referred to as "the Fukuoka Method", "the natural way of farming" or "do-nothing farming". The title refers not to lack of effort, but to the avoidance of manufactured inputs and equipment. Natural farming is related to fertility farming, organic farming, sustainable agriculture, agroecology, agroforestry, ecoagriculture and permaculture, but should be distinguished from biodynamic agriculture.

The system works along with the natural biodiversity of each farmed area, encouraging the complexity of living organisms—both plant and animal—that shape each particular ecosystem to thrive along with food plants.[2] Fukuoka saw farming both as a means of producing food and as an aesthetic or spiritual approach to life, the ultimate goal of which was, "the cultivation and perfection of human beings".[3][4] He suggested that farmers could benefit from closely observing local conditions.[5] Natural farming is a closed system, one that demands no human-supplied inputs and mimics nature.[6]

Fukuoka's ideas radically challenged conventions that are core to modern agro-industries; instead of promoting importation of nutrients and chemicals, he suggested an approach that takes advantage of the local environment.[7] Although natural farming is considered a subset of organic farming, it differs greatly from conventional organic farming,[8] which Fukuoka considered to be another modern technique that disturbs nature.[9]

Fukuoka claimed that his approach prevents water pollution, biodiversity loss and soil erosion, while providing ample amounts of food.[10]

Masanobu Fukuoka's principles

In principle, practitioners of natural farming maintain that it is not a technique but a view, or a way of seeing ourselves as a part of nature, rather than separate from or above it.[11] Accordingly, the methods themselves vary widely depending on culture and local conditions.

Rather than offering a structured method, Fukuoka distilled the natural farming mindset into five principles:[12]

- No tillage

- No fertilizer

- No pesticides or herbicides

- No weeding

- No pruning

Though many of his plant varieties and practices relate specifically to Japan and even to local conditions in subtropical western Shikoku, his philosophy and the governing principles of his farming systems have been applied widely around the world, from Africa to the temperate northern hemisphere.

Principally, natural farming minimises human labour and adopts, as closely as practical, nature's production of foods such as rice, barley, daikon or citrus in biodiverse agricultural ecosystems. Without plowing, seeds germinate well on the surface if site conditions meet the needs of the seeds placed there. Fukuoka used the presence of spiders in his fields as a key performance indicator of sustainability.

Fukuoka specifies that the ground remain covered by weeds, white clover, alfalfa, herbaceous legumes, and sometimes deliberately sown herbaceous plants. Ground cover is present along with grain, vegetable crops and orchards. Chickens run free in orchards and ducks and carp populate rice fields.[13]

Periodically ground layer plants including weeds may be cut and left on the surface, returning their nutrients to the soil, while suppressing weed growth. This also facilitates the sowing of seeds in the same area because the dense ground layer hides the seeds from animals such as birds.

For summer rice and winter barley grain crops, ground cover enhances nitrogen fixation. Straw from the previous crop mulches the topsoil. Each grain crop is sown before the previous one is harvested by broadcasting the seed among the standing crop. Later, this method was reduced to a single direct seeding of clover, barley and rice over the standing heads of rice.[14] The result is a denser crop of smaller, but highly productive and stronger plants.

Fukuoka's practice and philosophy emphasised small scale operation and challenged the need for mechanised farming techniques for high productivity, efficiency and economies of scale. While his family's farm was larger than the Japanese average, he used one field of grain crops as a small-scale example of his system.

Yoshikazu Kawaguchi

Widely regarded as the leading practitioner of the second-generation of natural farmers, Yoshikazu Kawaguchi is the instigator of Akame Natural Farm School, and a related network of volunteer-based "no-tuition" natural farming schools in Japan that numbers 40 locations and more than 900 concurrent students.[15] Although Kawaguchi's practice is based on Fukuoka's principals, his methods differ notably from those of Fukuoka. He re-states the core values of natural farming as:

- Do not plow the fields

- Weeds and insects are not your enemies

- There is no need to add fertilizers

- Adjust the foods you grow based on your local climate and conditions

Kawaguchi's recognition outside of Japan has become wider after his appearance as the central character in the documentary Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happiness, through which his interviews were translated into several languages.[16] He is the author of several books in Japan, though none have been officially translated into English.

Since 2016, Kawaguchi is no longer directly instructing at the Akame school which he founded. He is still actively teaching however, holding open farm days at his own natural farm in Nara prefecture.[17]

No-till

Natural farming recognizes soils as a fundamental natural asset. Ancient soils possess physical and chemical attributes that render them capable of generating and supporting life abundance. It can be argued that tilling actually degrades the delicate balance of a climax soil:

- Tilling may destroy crucial physical characteristics of a soil such as water suction, its ability to send moisture upwards, even during dry spells. The effect is due to pressure differences between soil areas. Furthermore, tilling most certainly destroys soil horizons and hence disrupts the established flow of nutrients. A study suggests that reduced tillage preserves the crop residues on the top of the soil, allowing organic matter to be formed more easily and hence increasing the total organic carbon and nitrogen when compared to conventional tillage. The increases in organic carbon and nitrogen increase aerobic, facultative anaerobic and anaerobic bacteria populations.[18]

- Tilling over-pumps oxygen to local soil residents, such as bacteria and fungi. As a result, the chemistry of the soil changes. Biological decomposition accelerates and the microbiota mass increases at the expense of other organic matter, adversely affecting most plants, including trees and vegetables. For plants to thrive a certain quantity of organic matter (around 5%) must be present in the soil.

- Tilling uproots all the plants in the area, turning their roots into food for bacteria and fungi. This damages their ability to aerate the soil. Living roots drill millions of tiny holes in the soil and thus provide oxygen. They also create room for beneficial insects and annelids (the phylum of worms). Some types of roots contribute directly to soil fertility by funding a mutualistic relationship with certain kinds of bacteria (most famously the rhizobium) that can fix nitrogen.

Fukuoka advocated avoiding any change in the natural landscape. This idea differs significantly from some recent permaculture practice that focuses on permaculture design, which may involve the change in landscape. For example, Sepp Holzer, an Austrian permaculture farmer, advocates the creation of terraces on slopes to control soil erosion. Fukuoka avoided the creation of terraces in his farm, even though terraces were common in China and Japan in his time. Instead, he prevented soil erosion by simply growing trees and shrubs on slopes.

Other forms of natural farming

Although the term "natural farming" came into common use in the English language during the 1980s with the translation of the book One Straw Revolution, the natural farming mindset itself has a long history throughout the world, spanning from historical Native American practices to modern day urban farms.[19][20][21]

Some variants, and their particularities include:

Fertility farming

In 1951, Newman Turner advocated the practice of "fertility farming", a system featuring the use of a cover crop, no tillage, no chemical fertilizers, no pesticides, no weeding and no composting. Although Turner was a commercial farmer and did not practice random seeding of seed balls, his "fertility farming" principles share similarities with Fukuoka's system of natural farming. Turner also advocate a "natural method" of animal husbandry.[22]

Native American

Recent research in the field of traditional ecological knowledge finds that for over one hundred centuries, Native American tribes worked the land in strikingly similar ways to today's natural farmers. Author and researcher M. Kat Anderson writes that "According to contemporary Native Americans, it is only through interaction and relationships with native plants that mutual respect is established."[21]

Nature Farming (Mokichi Okada)

Japanese farmer and philosopher Mokichi Okada, conceived of a "no fertilizer" farming system in the 1930s that predated Fukuoka. Okada used the same Chinese characters as Fukuoka's "natural farming" however, they are translated into English slightly differently, as nature farming.[23] Agriculture researcher Hu-lian Xu claims that "nature farming" is the correct literal translation of the Japanese term.[23]

Rishi Kheti

In India, natural farming of Masanobu Fukuoka was called "Rishi Kheti" by practitioners like Partap Aggarwal.[24][25] The Rishi Kheti use cow products like buttermilk, milk, curd and its waste urine for preparing growth promoters. The Rishi Kheti is regarded as non-violent farming without any usage of chemical fertilizer and pesticides. They obtain high quality natural or organic produce having medicinal values. Today still a small number of farmers in Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu use this farming method in India.

Zero Budget Farming

Zero Budget Farming is a variation on natural farming developed in, and primarily practiced in southern India. It also called spiritual farming .The method involves mulching, intercropping, and the use of several preparations which include cow dung. These preparations, generated on-site, are central to the practice, and said to promote microbe and earthworm activity in the soil.[26] Indian agriculturist Subhash Palekar has researched and written extensively on this method.

See also

References

- 1975 (in Japanese) 自然農法-わら一本の革命 (in English) 1978 re-presentation The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming.

- "Life and Death in the Field | Final Straw – Food | Earth | Happiness". www.finalstraw.org. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- Floyd, J.; Zubevich, K. (2010). "Linking foresight and sustainability: An integral approach". Futures. 42: 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2009.08.001.

- Hanley, Paul (1990). "Agriculture: A Fundamental Principle" (PDF). Journal of Bahá'í Studies. 3 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- Colin Adrien MacKinley Duncan (1996). The Centrality of Agriculture: Between Humankind and the Rest of Nature. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-6571-5.

- Trees on Organic Farms, Mirret, Erin Paige. North Carolina State University, 2001

- Stephen Morse; Michael Stockin (1995). People and Environment: Development for the Future. Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-85728-283-2.

- Elpel, Thomas J. (November 1, 2002). Participating in Nature: Thomas J. Elpel's Field Guide to Primitive Living Skills. ISBN 1892784122.

- What Does Natural Farming Mean? Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine by Toyoda, Natsuko

- Priya Reddy; Prescott College Environmental studies (2010). Sustainable Agricultural Education: An Experiential Approach to Shifting Consciousness and Practices. Prescott College. ISBN 978-1-124-38302-6.

- "Masanobu Fukuoka and Natural Farming | Final Straw – Food | Earth | Happiness". www.finalstraw.org. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- Helena Norberg-Hodge; Peter Goering; John Page (1 January 2001). From the Ground Up: Rethinking Industrial Agriculture. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-994-1.

- 1975 (in Japanese) 自然農法-わら一本の革命 (in English) 1978 re-presentation The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming

- Masanobu Fukuoka (1987). The Natural Way of Farming: The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy. Japan Publications. ISBN 978-0-87040-613-3.

- (Japan)), Hokazono, S.(Mie Univ., Tsu; K., Ohara (2007-01-01). "The role of a learning site for urban residents hoping to do farming: Focusing on the spread of 'natural farming' by the Akame Natural Farming School". Journal of Rural Problems (Japan) (in Japanese). ISSN 0388-8525.

- "Final Straw – Food - Earth - Happiness". www.finalstraw.org.

- "'Body and Earth Are Not Two': Kawaguchi Yoshikazu's NATURAL FARMING and American Agriculture Writers". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- Sylvia, D.M.; Fuhrmann, J.J.; Hartel, P.G.; Zuberer, D.A. (1999). Principles and Applications of Soil Microbiology. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0130941174.

- Lydon, Patrick (2015-09-16). "Social Practice Artwork: A Restaurant and Garden Serving up Connections to Urban Nature". The Nature of Cities. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- "Artwork / Urban Empathy Garden | SocieCity". sociecity.org. 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- ANDERSON, M. KAT (2005-01-01). "Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources". Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources (1 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 9780520238565. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppfn4.

- Newman Turner (1951). Fertility Farming. Faber and Faber Limited. ISBN 978-1601730091.

- Xu, Hui-Lian (2001). NATURE FARMING In Japan (Monograph). T. C. 37/661(2), Fort Post Office, Trivandrum - 695023, Kerala, India: Research Signpost. ISBN 81-308-0111-6. Retrieved 6 March 2011.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Masanobu Fukuoka: The man who did nothing By Malvika Tegta" "DNA Daily News and Analysis". "Published: Sunday, Aug 22, 2010, 2:59 IST". "Place: Mumbai", India. (Retrieved 1 December 2010)

- "Natural farming succeeds in Indian village By Partap C Aggarwal" in the 1980s Satavic Farms (India), "Slowly, bit by bit, we found ourselves close to what is called ‘natural farming’, pioneered in Japan by Masanobu Fukuoka. At Rasulia we called it 'rishi kheti' (agriculture of the sages)."

- "Zero Budget Natural Farming in India" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

External links

- Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happiness documentary exploring the natural farming philosophy in Korea, Japan, and USA (2015)

- The Natural Farming Center of Greece

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

|