Myometrium

The myometrium is the middle layer of the uterine wall, consisting mainly of uterine smooth muscle cells (also called uterine myocytes[1]) but also of supporting stromal and vascular tissue.[2] Its main function is to induce uterine contractions.

| Myometrium | |

|---|---|

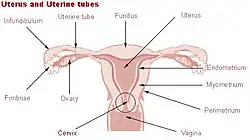

Uterus and uterine tubes (Myometrium labeled at center right) | |

Histology of myometrium | |

| Details | |

| Location | Uterus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica muscularis |

| MeSH | D009215 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.025 |

| TA2 | 3520 |

| FMA | 17743 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The myometrium is located between the endometrium (the inner layer of the uterine wall) and the serosa or perimetrium (the outer uterine layer).

The inner one-third of the myometrium (termed the junctional or sub-endometrial layer) appears to be derived from the Müllerian duct, while the outer, more predominant layer of the myometrium appears to originate from non-Müllerian tissue and is the major contractile tissue during parturition and abortion.[1] The junctional layer appears to function like a circular muscle layer, capable of peristaltic and anti-peristaltic activity, equivalent to the muscular layer of the intestines.[1]

Muscular structure

The molecular structure of the smooth muscle of myometrium is very similar to that of smooth muscle in other sites of the body, with myosin and actin being the predominant proteins.[1] In uterine smooth muscle, there is approximately 6-fold more actin than myosin.[1] A shift in the myosin expression of the uterine smooth muscle may be responsible for changes in the directions of uterine contractions during the menstrual cycle.[1]

Function

Contraction

The myometrium stretches (the smooth muscle cells expand in both size and number[3]) during pregnancy to allow for the uterus to become several times its non-gravid size, and contracts in a coordinated fashion, via a positive feedback effect on the "Ferguson reflex", during the process of labor. After delivery, the myometrium contracts to expel the placenta, and crisscrossing fibres of middle layer compress the blood vessels to minimize blood loss. A positive benefit to early breastfeeding is a stimulation of this reflex to reduce further blood loss and facilitate a swift return to prepregnancy uterine and abdominal muscle tone.

Uterine smooth muscle has a phasic pattern, shifting between a contractile pattern and maintenance of a resting tone with discrete, intermittent contractions of varying frequency, amplitude and duration.[1]

As noted for the macrostructure of uterine smooth muscle, the junctional layer appears to be capable of both peristaltic and anti-peristaltic activity.[1]

Resting state

The resting membrane potential (Vrest) of uterine smooth muscle has been recorded to be between -35 and -80 mV.[1] As with the resting membrane potential of other cell types, it is maintained by a Na+/K+ pump that causes a higher concentration of Na+ ions in the extracellular space than in the intracellular space, and a higher concentration of K+ ions in the intracellular space than in the extracellular space. Subsequently, having K+ channels open to a higher degree than Na+ channels results in an overall efflux of positive ions, resulting in a negative potential.

This resting potential undergoes rhythmic oscillations, which have been termed slow waves, and reflect intrinsic activity of slow wave potentials.[1] These slow waves are caused by changes in the distribution of Ca2+, Na+, K+ and Cl− ions between the intracellular and extracellular spaces, which, in turn, reflects the permeability of the plasma membrane to each of those ions.[1] K+ is the major ion responsible for such changes in ion flux, reflecting changes in various K+ channels.[1]

Excitation-contraction

The excitation-contraction coupling of uterine smooth muscle is also very similar to that of other smooth muscle in general, with intracellular increase in calcium (Ca2+) leading to contraction.

Restoration to resting state

Removal of Ca2+ after contraction induces relaxation of the smooth muscle, and restores the molecular structure of the sarcoplasmic reticulum for the next contractile stimulus.[1]

References

- Aguilar, H. N.; Mitchell, S.; Knoll, A. H.; Yuan, X. (2010). "Physiological pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating uterine contractility". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (6): 725–744. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq016. PMID 20551073.

- "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- Steven's and Lowe Histology p352