Mušḫuššu

The mušḫuššu (𒈲𒄭𒄊; formerly also read as sirrušu or sirrush) or mushkhushshu (pronounced [muʃxuʃʃu] or [musxussu]), is a creature from ancient Mesopotamian mythology. A mythological hybrid, it is a scaly animal with hind legs resembling the talons of an eagle, lion-like forelimbs, a long neck and tail, a horned head, a snake-like tongue, and a crest. The mušḫuššu most famously appears on the reconstructed Ishtar Gate of the city of Babylon, dating to the sixth century BCE.

| |

| Grouping | Mythological hybrid |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Sirrush |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

The form mušḫuššu is the Akkadian nominative of Sumerian: 𒈲𒄭𒄊 MUŠ.ḪUS, 'reddish snake', sometimes also translated as 'fierce snake'.[2] One author,[3] possibly following others, translates it as 'splendor serpent' (𒈲 MUŠ is the Sumerian term for 'serpent'). The reading sir-ruššu is due to a mistransliteration of the cuneiform in early Assyriology.[4]

History

Mušḫuššu already appears in Sumerian religion and art, as in the "Libation vase of Gudea", dedicated to Ningishzida by the Sumerian ruler Gudea (21st century BCE short chronology).[1][5]

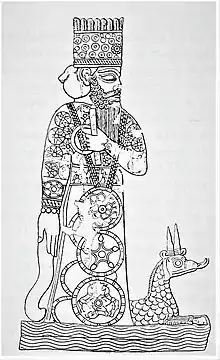

The mušḫuššu is the sacred animal of Marduk and his son Nabu during the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The dragon Mušḫuššu, whom Marduk once vanquished, became his symbolic animal and servant.[6] It was taken over by Marduk from Tishpak, the local god of Eshnunna.[7]

The constellation Hydra was known in Babylonian astronomical texts as Bašmu, 'the Serpent' (𒀯𒈲, MUL.dMUŠ). It was depicted as having the torso of a fish, the tail of a snake, the forepaws of a lion, the hind legs of an eagle, wings, and a head comparable to the mušḫuššu.[8][9]

9th century BCE depiction of the Statue of Marduk, with his servant dragon Mušḫuššu at his feet. This was Marduk's main cult image in Babylon.

9th century BCE depiction of the Statue of Marduk, with his servant dragon Mušḫuššu at his feet. This was Marduk's main cult image in Babylon..jpg.webp)

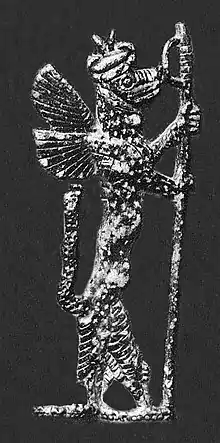

Head of dragon dating from the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626 BCE – 539 BCE) from the Louvre Museum's collection

Head of dragon dating from the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626 BCE – 539 BCE) from the Louvre Museum's collection

See also

References

- Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1992). Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts. Brill Publishers. p. 156. ISBN 978-90-72371-52-2.

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". The ETCSL project, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- Costello, Peter (1974). In Search of Lake Monsters. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan – via Internet Archive.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; Reiner, Erica, eds. (1977). The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (PDF). Volume 10: M, Part II. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Oriental Institute. p. 270. ISBN 0-918986-16-8.

- Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1992). Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts. Brill Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 978-90-72371-52-2.

- Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1992). Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts. Brill Publishers. p. 157. ISBN 978-90-72371-52-2.

- Bienkowski, Piotr; Millard, Alan Ralph (2000). Dictionary of the Ancient Near East. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8122-3557-9.

- Wiggerman, F. A. M. (1 January 1997). "Transtigridian Snake Gods". In Finkel, I. L.; Geller, M. J. (eds.). Sumerian Gods and their Representations. Cuneiform Monographs. 7. Gronigen, Netherlands: Styx Publications. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-90-56-93005-9.

- E. Weidner, Gestirn-Darstellungen auf Babylonischen Tontafeln (1967) Plates IX–X.

Notes

- 1.^ Similar to the Set animal in Egyptian mythology and the Qilin in Chinese mythology.

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg.webp)