Mount Tom (Massachusetts)

Mount Tom, 1,202 feet (366 m), is a steep, rugged traprock mountain peak on the west bank of the Connecticut River 4.5 miles (7 km) northwest of downtown Holyoke, Massachusetts. The mountain is the southernmost and highest peak of the Mount Tom Range and the highest traprock peak of the 100-mile (160 km) long Metacomet Ridge. A popular outdoor recreation resource, the mountain is known for its continuous line of cliffs and talus slopes visible from the south and west, its dramatic 1,100-foot (340 m) rise over the surrounding Connecticut River Valley, and its rare plant communities and microclimate ecosystems.[1][2]

| Mount Tom | |

|---|---|

Mount Tom's east face and the Connecticut River, from the Joseph Muller Bridge | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,202 ft (366 m) |

| Prominence | 961 ft (293 m) |

| Coordinates | 42°14′30″N 72°38′53″W |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Named for surveyor Rowland Thomas |

| Geography | |

| Location | Holyoke and Easthampton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Parent range | Mount Tom Range / Metacomet Ridge |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 200 Ma |

| Mountain type | Fault-block; igneous |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Metacomet-Monadnock Trail |

Located in Easthampton and Holyoke, Mount Tom is traversed by the 110-mile (180 km) Metacomet-Monadnock Trail and is the transmitter location for three Springfield–Holyoke television stations: WGBY, WGGB, and WSHM-LD, and for radio stations WHYN-FM and WWEI. The name "Mount Tom" is sometimes used to describe the entire Mount Tom Range.[1]

History

.tiff.jpg.webp)

According to popular folklore, Mount Tom takes its name from Rowland Thomas, a surveyor who worked for the settlement of Springfield, Massachusetts in the 1660s. Thomas supposedly named Mount Tom after himself while his fellow surveyor working on the opposite side of the Connecticut River, Elizur Holyoke, gave his name to Mount Holyoke.[3]

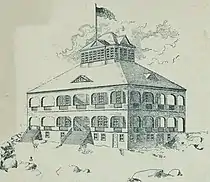

In 1897 the Holyoke Street Railway Company began constructing the Mount Tom Railroad, as well as what would become known as "Mountain Park", a trolley park and later an amusement park on the east side of the mountain. The project changed hands several times until its closure in 1988 when competition from larger amusement parks gradually sapped business away from what had become affectionately known by local residents as "The Queen of the Mountain".[4][5] The Mount Tom Summit House was also constructed on the cliffs of Mount Tom in 1897, but it burned three years later. Subsequently, rebuilt, by 1902, the property became the first parcel of the Mount Tom State Reservation, however this second house also burned in 1929, in part due to a series of failures in its water systems. The original foundation was not used again, however days later it was decided a much cheaper and smaller sheet metal structure would be built adjacent to it, housing a restaurant and souvenir stand. Because of its construction and lack of grandeur however, it remained unpopular, with one local patron, Katherine Root, remarking "the wind sounded like thunder when it roared through the building and it rattled constantly"; it was ultimately dismantled a year after the railroad, in 1939.[6] The ruins of the old summit house foundations remain prominent structures, visible on the mountainside today. In 1933 the Civilian Conservation Corps assisted with the construction of reservation structures and park roads; their work also remains visible today.

During the heyday of northern New England's logging and river drives during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the spring freshet, augmented by impoundments called drive-dams or squirt-dams on far-flung upper tributaries, carried logs rolled into rivers and lakes far down the Connecticut River to mills at falls where the river was pinched by bedrock at Mount Tom. For many logging company workers, the specialists called river-hogs, the end of the drive at Mount Tom spelled the end of their employment until they joined crews going into the woods the next fall.

On July 9, 1946, a US Army Air Force B-17G Flying Fortress, in use as a military transport, hit the northern flank of the mountain.[7] All 25 on board died instantly in a large fireball. Some of the men were Public Health employees of the US military who had worked in Europe in World War II. Sixteen were U.S. Coast Guardsmen returning from duty in Greenland.[8] Tiny pieces of the plane are still on the mountainside, and the site is accessible on a road built over the former funicular railway to access antennae at the summit. A memorial site, dedicated 6 July 1996, is at the location and is lit at all times.[9]

Geology and ecology

Mount Tom, like much of the Metacomet Ridge, is composed of basalt, also called traprock, a volcanic rock. The mountain formed near the end of the Triassic Period with the rifting apart of the North American continent from Africa and Eurasia. Lava welled up from the rift and solidified into sheets of strata hundreds of feet thick. Subsequent faulting and earthquake activity tilted the strata, creating the dramatic cliffs and ridges of Mount Tom.[10] Hot, dry upper slopes, cool, moist ravines, and mineral-rich ledges of basalt talus produce a combination of microclimate ecosystems on the mountain that support plant and animal species uncommon in greater Massachusetts.[2] (See Metacomet Ridge for more information on the geology and ecosystem of Mount Nonotuck.)

Recreation

Mount Tom is a popular outdoor recreation resource; the summit is crossed by the 110-mile (180 km) Metacomet-Monadnock Trail as well as a network of shorter hiking trails and a park road that passes beneath the western cliff face. The road is used for bicycling, running, and mountain biking, and in the winter, cross country skiing and ski touring. Geocaching is popular. The mountain is also well known as a place to watch seasonal raptor migrations; an observation tower on nearby Goat Peak is maintained for that purpose.[1][11] Mount Tom is registered in Amateur Radio as SOTA W1/MB-006.[12]

Conservation

Most of Mount Tom has been conserved as part of Massachusetts' Mount Tom State Reservation, conservation easement, or watershed protection land. The mountain was also once home to the Mount Tom Ski Area that operated from 1962 to 1998;[13] although the ski area is closed, the slopes are still used for backcountry skiing, and the defunct ski area has been conserved by the concerted efforts of several non-profit organizations and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. These groups do not plan on re-opening the ski area.[14]

Cultural references

- Mount Tom is mentioned by the eponymous protagonist in Henry James's 1875 novel Roderick Hudson, chapter IX.

- Mount Tom may have been Dr. Seuss' inspiration for the mountain overlooking Whoville, though this claim is controversial.

- In 1865, the British painter Thomas Charles Farrer completed a painting of Mount Tom. Farrer alludes to the end of the American Civil War by including a man in Union Army attire.

See also

- Mount Tom is also the name of 42 other mountains in the United States. Other regional examples with which it may be confused include:

- Mount Tom (Connecticut)

- Mount Tom (New Hampshire)

- Mount Tom (Rhode Island)

- Tom Ball Mountain (Massachusetts)

References

- The Metacomet-Monadnock Trail Guide. 9th Edition. The Appalachian Mountain Club. Amherst, Massachusetts, 1999.

- Farnsworth, Elizabeth J. "Metacomet-Mattabesett Trail Natural Resource Assessment. Archived 2007-08-07 at the Wayback Machine" 2004. PDF wefile cited November 1, 2007.

- Harper, Wyatt. The Story of Holyoke. Holyoke Centennial Committee, Holyoke, Massachusetts 1973.

- "Queen of the Mountain" Defunctparks.com cited Dec. 21, 2007.

- Mt. Holyoke Range Historical Timeline Website cited November 12, 2007.

- Connolly-Cowdrey, Patricia (March 1984). "A Time of Passing Glory". Timeless Images, Greater Holyoke Edition. Vol. II no. IV. pp. 8, 9.

- "Mt. Tom B-17". www.check-six.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2014-03-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mt. Tom, MA Bomber Crashes Into Mount Tom, July 1946 - GenDisasters ... Genealogy in Tragedy, Disasters, Fires, Floods". www3.gendisasters.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Raymo, Chet and Raymo, Maureen E. Written in Stone: A Geologic History of the Northeastern United States. Globe Pequot, Chester, Connecticut, 1989.

- Massachusetts DCR. Cited Dec. 1, 2007.

- "Associations". www.sotawatch.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- New England Lost Ski Area Project. Cited. Dec. 2, 2007.

- The Trustees of the Reservation. Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Cited Dec. 21, 2007.