Monastic garden

A monastic garden was used by many people and for multiple purposes. Gardening was the chief source of food for households, but also encompassed orchards, cemeteries and pleasure gardens, as well as providing plants for medicinal and cultural uses. Gardening is the deliberate cultivation of plants herbs, fruits, flowers, or vegetables.

Gardening was especially important in the monasteries, in supplying their livelihood.[1] Many of the plants had multiple uses: for example, peaches were used for closing wounds.[2]

Historical evidence

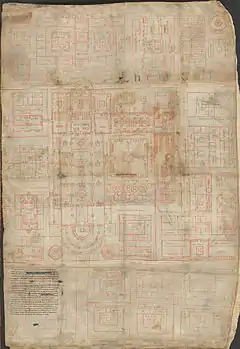

The majority of data about gardens in the Middle Ages comes through archaeology, textual documentation, and artworks such as paintings, tapestry and illuminated manuscripts. The early Middle Ages brings a surprisingly clear snapshot of gardening at the time of Charlemagne with the survival of three important documents: the Capitulare de villis, Walafrid Strabo's poem Hortulus, and the plan of St Gall which depicts three garden areas and lists what was grown.

Main uses

Gardens were mainly in monasteries and manors, but were also developed by peasants. Gardens were used as kitchen gardens, herbal gardens, and even orchards and cemetery gardens, among others. Each type of garden had its own purpose and meaning, including satisfying medicinal, food, and spiritual needs.

Medicinal

Gardening was particularly important for medicinal use.[1][2][3][4] For example, when the peel of the poppy stalk was ground and mixed with honey, it could be used as a plaster for wounds.[2] Other herbs and plants were used for internal complications, such as a headache or stomachache. Almonds were said to aid sleep, provoke urination, and induce menstruation.[2] Other herbs include roses, lilies, sage, rosemary and other aromatic herbs.[5]

Monks used these medicinal herbs on themselves and on the local community. One prominent healer was Hildegard of Bingen, a woman who lived in a monastery housing both men and women and eventually was elected magistra and later cared for her own secluded monastery.[4] Besides her extensive writing, Hildegard was regularly visited by people throughout Europe, including Henry II of England, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the empress of Byzantium, as well as the local community. Hildegard was seen as the “first woman physician” because of her work as a healer and medical writings.[4]

Food

A general garden was needed for food supply. Some vegetables could also be used for medicinal purposes, such as garlic. Monks had a mainly vegetarian diet.[5] Vegetables high in starch or in flavor were sought after for the gardens. Cottage gardens were widely used to grow vegetables, and typically looked wild. However, patches in the cottage garden were found to be grouped by vegetable family, such as the Allium family, consisting of the leek (Allium porrum), onion (Allium cepa), and garlic (Allium sativum). Common vegetables included:

- Leek (Allium porrum)

- Onion (Allium cepa)

- Garlic (Allium sativum)

- Shallots (Allium cepa)

- Carrots (Daucus carota)

- Parsnips (Pastinaca sativa)

- Chives (Allium schoenoprasum)

- Kale (Brassica oleracea)

- White/headed cabbage (Brassica oleracea)

- Heart cabbage (Brassica oleracea)

- Roman cabbage (Brassica oleracea)

- Cauliflower/cole wort (Brassica oleracea)

- Plain coles/rape (Brassica napus)

- Turnip/neeps (Brassica rapa)

- White beet (Beta vulgaris)

- Radish (Raphanus sativus)

- Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

- White pea (Pisum sativum)

- Green pea (Pisum sativum)

- Beans (Faba vulgaris)[6]

Orchards and cemetery gardens

Orchards and cemetery gardens were also tended to in medieval monasteries. The vegetation would provide fruit, such as apples or pears, as well as manual labor for the monks as was required by the Rule of Saint Benedict. According to Saint Benedict, idleness is the enemy of the soul, and for a monk, daily life was meant to be spent learning about the Lord and fighting that spiritual battle for the soul.[7] So, monks used manual labor and spiritual reading to keep busy and avoid being idle. Cemetery gardens, which tended to be very similar to generic orchards, also acted as a symbol of Heaven and Paradise, and thus provided spiritual meaning.

Contents

.jpg.webp)

Monks of this time typically would use astronomy and the stars to determine religious holidays for every year. They also used astronomy to help in figuring the best time of year to plant their gardens as well as the best time to harvest.[3] Concerning the structure of the gardens, they often were enclosed with fences, walls or hedges in order to protect them. Stone and brick walls were typically used by the wealthy, such as manors and monasteries. However, wattle fences were used by all classes and were the most common type of fence. They were made using local saplings and woven together. They were easily accessible and durable, and could even be used to make beds. Bushes were also used as fencing, as they provided both food and protection to the garden. Gardens were typically arranged to allow for visitors, and were constructed with pathways for easy access.[6] However, it was not uncommon for the gardens to outgrow the monastery walls, and many times the gardens extended outside of the monastery and would eventually include vineyards as well.[5]

An irrigation and water source was imperative to keeping the garden alive. The most complicated irrigation system used canals. This required that the water source be placed at the highest part of the garden so gravity could aid in the distribution of the water. This was more commonly used with raised bed gardens, as the channels could run in the pathways next to the beds. Kitchen garden ponds also were used in the 14th and 15th centuries, and were meant to offer ornamental value as well. Manure was placed in the ponds to provide fertilization and water was taken straight from the pond to water the plants.

The tools that were used at the time were similar to those gardeners use today. For instance, shears, rakes, hoes, spades, baskets, and wheel barrows were used and are still important today. There was even a tool that acted much like a watering can, called a thumb pot. Made from clay, the thumb pot has small holes at the bottom and a thumb hole at the top. The pot was submerged in water, and the thumb hole covered until the water was needed. A perforated pot was also used to hang over plants for constant moisture.[6]

Primary sources on gardening

- Apuleius, Herbal 11th century

- Charlemagne, Capitulare de villis (c. 800): listing the plants and estate style to be established throughout his empire

- Palladius, Palladius On husbondrie. c. 1420

- Walahfrid Strabo, Hortulus

- Jon Gardener, The Feate of Gardening. c. 1400: poem containing plant lists and outlining gardening practices, probably by a royal gardener

- Friar Henry Daniel (14th century): compiled a list of plants

- Albertus Magnus, De vegetabilibus et plantis (c. 1260): records design precepts on the continent

- Piero de' Crescenzi, Ruralium Commodorum Liber (c. 1305): records designs precepts on the continent

- 'Fromond List', original titled Herbys necessary for a gardyn (c. 1525): list of garden plants

- Thomas Hill (born c. 1528).

- Master Fitzherbert, The Booke of Husbandrie (1534): includes commentary on past horticultural practices

- T. Tusser, Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry (1580): another relevant commentary though written in the post medieval period[8]

Other sources on medieval gardening

- Crisp, Frank; Mediaeval Gardens

- Landsberg, Sylvia; The Medieval Garden 1995

- Wright, Richardson; The Story of Gardening from the Hanging Gardens of Babylon to the Hanging Gardens of New York, 1934

- John Harvey; Mediaeval Gardens

See also

References

- Voigts, L.E. (1979). Anglo-Saxon Plant Remedies and the Anglo-Saxons. Isis, 70(2): 250-268

- Wallis, F. (2010). Medieval Medicine: A Reader. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press

- McCluskey, S.C. (1990). Gregory of Tours, Monastic Timekeeping, and Early Christian Attitudes to Astronomy. Isis, 81(1): 8-22

- Sweet, V. (1999). Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 73(3): 381-403

- http://www.gardenvisit.com/history_theory/library_online_ebooks/ml_gothein_history_garden_art_design/monastery_garden_plans

- http://renaissancegardens.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/kitchengardenreport.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-13. Retrieved 2014-05-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Landsberg Sylvia, The Medieval Garden, The British Museum Press (ISBN 0-7141-0590-2), passim

External links

- Penn State Medieval Garden recreation

- Bodleian Library, Tradescant's Orchard, watercolours of garden fruits, c. 1620

- Gode Cookery, Tacuinum Sanitatis, medieval cooking

- Karolus Magnus, Capitulare de villis (Latin), c. 795

- Garden blog at the Cloisters, NYC

- Marian's Medieval Gardening Author list

- Garden blog at High Bridge, NJ