Moab

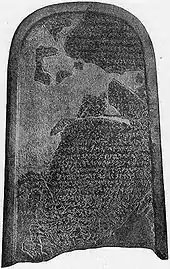

Moab[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈmoʊæb/) is the name of an ancient kingdom whose territory is today located in the modern state of Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by numerous archaeological findings, most notably the Mesha Stele, which describes the Moabite victory over an unnamed son of King Omri of Israel, an episode also noted in 2 Kings 3. The Moabite capital was Dibon. According to the Hebrew Bible, Moab was often in conflict with its Israelite neighbours to the west.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Jordan |

|

| Ancient history |

| Classical period |

| Islamic era |

| Emirate and mandate |

| Post-independence |

|

|

Kingdom of Moab | |

|---|---|

| c. 13th century BC–c. 400 BC | |

| |

| Status | Monarchy |

| Capital | Dibon |

| Common languages | Moabite |

| History | |

• Established | c. 13th century BC |

• Collapsed | c. 400 BC |

| Today part of | |

| mwjbw "Moab" in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Etymology

The etymology of the word Moab is uncertain. The earliest gloss is found in the Koine Greek Septuagint (Genesis 19:37) which explains the name, in obvious allusion to the account of Moab's parentage, as ἐκ τοῦ πατρός μου ("from my father"). Other etymologies which have been proposed regard it as a corruption of "seed of a father", or as a participial form from "to desire", thus connoting "the desirable (land)". Rashi explains the word Mo'ab to mean "from the father", since ab in Hebrew and Arabic and the rest of the Semitic languages means "father". He writes that as a result of the immodesty of Moab's name, God did not command the Israelites to refrain from inflicting pain upon the Moabites in the manner in which he did with regard to the Ammonites. Fritz Hommel regards Moab as an abbreviation of Immo-ab = "his mother is his father".[1]

According to Genesis 19:30–38, the ancestor of the Moabites was Lot by incest with his eldest daughter. She and her sister, having lost their fiancés and their mother in the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, decided to continue their father's line through intercourse with their father. The elder got him drunk to facilitate the deed and conceived Moab. The younger daughter did the same and conceived a son named Ben-Ammi, who became ancestor to the Ammonites. According to the Book of Jasher (24,24), Moab had four sons—Ed, Mayon, Tarsus and Kanvil—and his wife, whose name is not given, is apparently from Canaan.

Geography

Topography

Moab was located on a plateau about 910 metres (3,000 ft) above the level of the Mediterranean, or 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) above the Dead Sea, rising gradually from north to south.

In the north are a number of long, deep ravines, and Mount Nebo, famous as the scene of the death of Moses (Deuteronomy 34:1–8).

Biblical boundaries

It was bounded on the west by the Dead Sea; on the east by Ammon and the Arabian Desert, from which it was separated by low, rolling hills; and on the south by Edom. The northern boundary varied, but generally is represented by a line drawn some miles above the northern extremity of the Dead Sea.

In Ezekiel 25:9 the boundaries are given as being marked by Beth-jeshimoth (north), Baal-meon (east), and Kiriathaim (south).

That these limits were not fixed, however, is plain from the lists of cities given in Isaiah 15–16 and Jeremiah 48, where Heshbon, Elealeh, and Jazer are mentioned to the north of Beth-jeshimoth; Madaba, Beth-gamul, and Mephaath to the east of Baalmeon; and Dibon, Aroer, Bezer, Jahaz, and Kirhareseth to the south of Kiriathaim. The principal rivers of Moab mentioned in the Bible are the Arnon, the Dimon or Dibon, and the Nimrim.

The territory occupied by Moab at the period of its greatest extent, before the invasion of the Amorites, divided itself naturally into three distinct and independent portions: the enclosed corner or canton south of the Arnon, referred to in the Bible as "field of Moab" (Ruth 1:1,2,6). The more open rolling country north of the Arnon, opposite Jericho and up to the hills of Gilead, called the "land of Moab" (Deuteronomy 1:5; 32:49) and the district below sea level in the tropical depths of the Jordan valley (Numbers 22:1).

Soil and vegetation

The limestone hills which form the almost treeless plateau are generally steep but fertile. In the spring they are covered with grass and the table-land itself produces grain. The rainfall is fairly plentiful and the climate, despite the hot summer, is cooler than the area west of the Jordan river, snow falling frequently in winter and in spring.

Economy

The country of Moab was the source of numerous natural resources, including limestone, salt and balsam from the Dead Sea region. The Moabites occupied a vital place along the King's Highway, the ancient trade route connecting Egypt with Mesopotamia, Syria, and Anatolia. Like the Edomites and Ammonites, trade along this route gave them considerable revenue.

History

Bronze Age

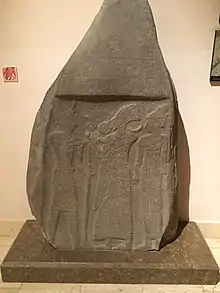

Despite a scarcity of archaeological evidence, the existence of Moab prior to the rise of the Israelite state has been deduced from a colossal statue erected at Luxor by pharaoh Ramesses II, in the 13th century BCE, which lists Mu'ab among a series of nations conquered during a campaign.

Iron Age

In the Nimrud clay inscription of Tiglath-pileser III (r. 745–727 BCE), the Moabite king Salmanu (perhaps the Shalman who sacked Beth-arbel in Hosea 10:14) is mentioned as tributary to Assyria. Sargon II mentions on a clay prism a revolt against him by Moab together with Philistia, Judah, and Edom; but on the Taylor prism, which recounts the expedition against Hezekiah, Kammusu-Nadbi (Chemosh-nadab), King of Moab, brings tribute to Sargon as his suzerain. Another Moabite king, Mutzuri ("the Egyptian"?), is mentioned as one of the subject princes at the courts of Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal, while Kaasḥalta, possibly his successor, is named on cylinder B of Assurbanipal.

Sometime during the Persian period Moab disappears from the extant historical record. Its territory was subsequently overrun by waves of tribes from northern Arabia, including the Kedarites and (later) the Nabataeans. In Nehemiah 4:1 the Arabs are mentioned instead of the Moabites as the allies of the Ammonites.[2]

Crusader period

When the Crusaders occupied the area, the castle they built to defend the eastern part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was called Krak des Moabites.

19th-century travellers

Early modern travellers in the region included Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (1805), Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1812), Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangles (1818), and Louis Félicien de Saulcy (1851).[3]

Biblical and other narratives

According to the biblical account, Moab and Ammon were born to Lot and Lot's elder and younger daughters, respectively, in the aftermath of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. The Bible refers to both the Moabites and Ammonites as Lot's sons, born of incest with his daughters (Genesis 19:37–38).

The Moabites first inhabited the rich highlands at the eastern side of the chasm of the Dead Sea, extending as far north as the mountain of Gilead, from which country they expelled the Emim, the original inhabitants (Deuteronomy 2:11), but they themselves were afterward driven southward by warlike tribes of Amorites, who had crossed the river Jordan. These Amorites, described in the Bible as being ruled by King Sihon, confined the Moabites to the country south of the river Arnon, which formed their northern boundary (Numbers 21:13; Judges 11:18).

God renewed his covenant with the Israelites at Moab before the Israelites entered the "promised land" (Deuteronomy 29:1). Moses died there (Deut 34:5), prevented by God from entering the Promised Land. He was buried in an unknown location in Moab and the Israelites spent a period of thirty days there in mourning (Deuteronomy 34:6–8).

According to the Book of Judges, the Israelites did not pass through the land of the Moabites (Judges 11:18), but conquered Sihon's kingdom and his capital at Heshbon. After the conquest of Canaan the relations of Moab with Israel were of a mixed character, sometimes warlike and sometimes peaceable. With the tribe of Benjamin they had at least one severe struggle, in union with their kindred the Ammonites and the Amalekites (Judges 3:12–30). The Benjaminite shofet Ehud ben Gera assassinated the Moabite king Eglon and led an Israelite army against the Moabites at a ford of the Jordan river, killing many of them.

The Book of Ruth testifies to friendly relations between Moab and Bethlehem, one of the towns of the tribe of Judah. By his descent from Ruth, David may be said to have had Moabite blood in his veins. He committed his parents to the protection of the king of Moab (who may have been his kinsman), when hard pressed by King Saul. (1 Samuel 22:3,4) But here all friendly relations stop forever. The next time the name is mentioned is in the account of David's war, who made the Moabites tributary (2 Samuel 8:2; 1 Chronicles 18:2). Moab may have been under the rule of an Israelite governor during this period; among the exiles who returned to Judea from Babylonia were a clan descended from Pahath-Moab, whose name means "ruler of Moab".

After the destruction of the First Temple, the knowledge of which people belonged to which nation was lost and the Moabites were treated the same as other gentiles. As a result, all members of the nations could convert to Judaism without restriction. The problem in Ezra and Nehemiah occurred because Jewish men married women from the various nations without their first converting to Judaism (Nehemiah 13:23–24).

At the disruption of the kingdom under the reign of Rehoboam, Moab seems to have been absorbed into the northern realm. It continued in vassalage to the Kingdom of Israel until the death of Ahab which according to E. R. Thiele's reckoning was in about 853 BCE,[4] when the Moabites refused to pay tribute and asserted their independence, making war upon the kingdom of Judah (2 Chronicles 22:1).

After the death of Ahab in about 853 BCE, the Moabites under Mesha rebelled against Jehoram, who allied himself with Jehoshaphat, King of the Kingdom of Judah, and with the King of Edom. According to the Bible, the prophet Elisha directed the Israelites to dig a series of ditches between themselves and the enemy, and during the night these channels were miraculously filled with water which was as red as blood.

According to the biblical account, the crimson color deceived the Moabites and their allies into attacking one another, leading to their defeat at Ziz, near En Gedi (2 Kings 3; 2 Chronicles 20). According to Mesha's inscription on the Mesha Stele, however, he was completely victorious and regained all the territory of which Israel had deprived him. The battle of Ziz is the last important date in the history of the Moabites as recorded in the Bible. In the year of Elisha's death they invaded Israel (2 Kings 13:20) and later aided Nebuchadnezzar in his expedition against Jehoiakim (2 Kings 24:2).

Although allusions to Moab are frequent in the prophetical books (Isa 25:10; Ezek 25:8–11; Amos 2:1–3; Zephaniah 2:8–11), and although two chapters of Isaiah (15 and 16) and one of Jeremiah (48) are devoted to the "burden of Moab", they give little information about the land. Its prosperity and pride, which the Israelites believed incurred the wrath of God, are frequently mentioned (Isa 16:6; Jer 48:11–29; Zephaniah 2:10), and their contempt for Israel is once expressly noted (Jer. 48:27).

Moab is also made reference to in the 2 Meqabyan, a book considered canonical in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[5] In that text, a Moabite king named Maccabeus joins forces with Edom and Amalek to attack Israel, later repenting of his sins and adopting the Israelite religion.

Religion

References to the religion of Moab are scant. Most of the Moabites followed the ancient Semitic religion like other ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, and the Book of Numbers says that they induced the Israelites to join in their sacrifices (Num 25:2; Judges 10:6). Their chief god was Chemosh (Jer 48:7, 48:13), and the Bible refers to them as the "people of Chemosh" (Num 21:29; Jer 48:46).

According to II Kings, at times, especially in dire peril, human sacrifices were offered to Chemosh, as by Mesha, who gave up his son and heir to him (2 Kings 3:27). Nevertheless, King Solomon built a "high place" for Chemosh on the hill before Jerusalem (1 Kings 11:7), which the Bible describes as "this detestation of Moab". The altar was not destroyed until the reign of Josiah (2 Kings 23:13). The Moabite Stone also mentions (line 17) a female counterpart of Chemosh, Ashtar-Chemosh, and a god Nebo (line 14), probably the well-known Babylonian divinity Nabu.

Language

The Moabite language was spoken in Moab. It was a Canaanite language closely related to Biblical Hebrew, Ammonite and Edomite,[6] and was written using a variant of the Phoenician alphabet.[7] Most of our knowledge of it comes from the Mesha Stele,[7] which is the only known extensive text in this language. In addition, there are the three line El-Kerak Inscription and a few seals.

The Moabites in Jewish tradition

According to the Bible, the Moabites opposed the Israelite invasion of Canaan, as did the Ammonites. As a consequence, they were excluded from the congregation for ten generations (Deuteronomy 23:4; comp. Nehemiah 8:1–3). The term "tenth generation" is considered an idiom, used for an unlimited time, as opposed to the third generation, which allows an Egyptian convert to marry into the community. The Talmud expresses the view that the prohibition applied only to male Moabites, who were not allowed to marry born Jews or legitimate converts. Female Moabites, when converted to Judaism, were permitted to marry with only the normal prohibition of a convert marrying a kohen (priest) applying. However, the prohibition was not followed during the Exile, and Ezra and Nehemiah sought to compel a return to the law because men had been marrying women who had not been converted at all (Ezra 9:1–2, 12; Nehemiah 13:23–25). The heir of King Solomon was Rehoboam, the son of an Ammonite woman, Naamah (1 Kings 14:21).

On the other hand, the marriages of the Bethlehem Ephrathites (of the tribe of Judah) Chilion and Mahlon to the Moabite women Orpah and Ruth (Ruth 1:2–4), and the marriage of the latter, after her husband's death, to Boaz (Ruth 4:10–13) who by her was the great-grandfather of David, are mentioned with no shade of reproach. The Talmudic explanation, however, is that the language of the law applies only to Moabite and Ammonite men (Hebrew, like all Semitic languages, has grammatical gender). The Talmud also states that the prophet Samuel wrote the Book of Ruth to settle the dispute as the rule had been forgotten since the time of Boaz. Another interpretation is that the Book of Ruth is simply reporting the events in an impartial fashion, leaving any praise or condemnation to be done by the reader.

The Babylonian Talmud in Yevamot 76B explains that one of the reasons was the Ammonites did not greet the Children of Israel with friendship and the Moabites hired Balaam to curse them. The difference in the responses of the two people led to God allowing the Jewish people to harass the Moabites (but not go to war) but forbade them to even harass the Ammonites (Deuteronomy 23:3–4).

Ruth adopted the god of Naomi, her Israelite mother-in-law. Ruth chose to go back to Naomi's people after her husband, his brother and his father, Naomi's husband, died.

Ruth said to Naomi, "Whither thou goest, I will go; whither thou lodgest, I will lodge; thy people shall be my people and thy God my God". The Talmud uses this as the basis for what a convert must do to be converted. There are arguments as to exactly when she was converted and if she had to repeat the statement in front of the court in Bethlehem when they arrived there.

According to the Book of Jeremiah, Moab was exiled to Babylon for his arrogance and idolatry. According to Rashi, it was also due to their gross ingratitude even though Abraham, Israel's ancestor, had saved Lot, Moab's ancestor from Sodom. Jeremiah prophesies that Moab's captivity will be returned in the end of days.[8]

Notes

References

- Leyden (1904). Verhandlungen des Zwölften Internationalen Orientalisten-Congresses. p. 261.

- comp. 1 Macc 9:32–42; Josephus, Jewish Antiquities xiii. 13, § 5; xiv. 1, § 4.

- Miller, Max (1997). "Ancient Moab: Still Largely Unknown". In George Ernest Wright; Frank Moore Cross; Edward Fay Campbell (eds.). The Biblical Archaeologist. 60. American Schools of Oriental Research. pp. 194–204. JSTOR 3210621.

Among the travellers who traversed the whole Moabite plateau including Moab proper prior to 1870 and whose published observations deserve special mention are Ulrich Seetzen (1805), Ludwig Burckhardt (1812), Charles Irby and James Mangles (1818), and Louis de Saulcy (1851). Both Seetzen and Burckhardt died during the course of their travels, and their travel journals were edited and published posthumously by editors who did not always understand the details. Burckhardt's journal was published first, in 1822, and served as the basis for the Moab segment of Edward Robinson's map of Palestine published in 1841. Robinson's map depicts several strange features for the Moab segment, most of which can be traced to editorial mistakes in Burckhardt's journal and/or to entirely understandable misinterpretations of the journal on Robinson's part. Unfortunately, these strange features would linger on in maps of Palestine throughout the nineteenth century.

- Edwin Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257.

- "Torah of Yeshuah: Book of Meqabyan I - III".

- Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2020). "Moabite". Glottolog 4.3.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (2007). "Moab". The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 395. ISBN 9780802837851.

- Jeremiah 48, Tanach. Brooklyn, New York: ArtScroll. p. 1187.

Further reading

- Many comparisons of Biblical Hebrew with the language of the Mêša˓ inscription appear in Wilhelm Gesenius' Hebrew grammar, e.g. §2d, §5d, §7b, §7f, §49a, §54l, §87e, §88c, §117b, etc.

- Routledge, Bruce (2004-07-26). Moab in the Iron Age: Hegemony, Polity, Archaeology. ISBN 9780812238013.. The most comprehensive treatment of Moab to date.

- Bienkowski, Piotr (1992). Early Edom and Moab: The Beginning of the Iron Age in Southern Jordan. ISBN 9780906090459.

- Dearman, John Andrew (1989). Studies in the Mesha Inscription and Moab. ISBN 9781555403577.

- Jacobs, Joseph and Louis H. Gray. "Moab". Jewish Encyclopedia. Funk and Wagnalls, 1901–1906, which cites to the following bibliography:

- Tristram, The Land of Moab, London, 1874.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moab. |

- Gutenberg E-text of Patriarchal Palestine by Archibald Henry Sayce (1895)

- Moab entry in Smith's Bible Dictionary