Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway

The Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway (M&GNJR) was a railway network in England, in the area connecting southern Lincolnshire, the Isle of Ely and north Norfolk. It developed from several local independent concerns and was incorporated in 1893. It was jointly owned by the Midland Railway and the Great Northern Railway, and those companies had long sponsored and operated the predecessor companies.

| Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Status | Defunct |

| Locale | East of England |

| Service | |

| Type | Regional rail |

| History | |

| Opened | 1893 |

| Closed | 1959 |

| Technical | |

| Track length | 180 miles (290 km) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

The area directly served was agricultural and sparsely populated, but seaside holidays had developed and the M&GNJR ran many long-distance express trains to and from the territory of the parent companies, as well as summer local trains for holidaymakers. It had the longest mileage of any joint railway in the United Kingdom.[1]

After 1945 the profitability of the network declined steeply, worsened by the seasonality of the business. It was duplicated by other lines and the decision was taken to close it. Most of the network closed in 1959, although some limited sections continued in use. Only a short section near Sheringham is in commercial use today, but the North Norfolk Railway is active as a heritage line.[2][3][4]

First railways

The area eventually served by the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway, taken as south Lincolnshire and north Norfolk, was late to be supplied with railway connections. The Great Northern Railway, running north through Huntingdon, Peterborough and on to Grantham, so forming the western edge of the area, was not authorised until 1846 and not opened until 1848 between Peterborough and Lincoln. The Eastern Counties Railway, authorised in 1836, aspired to reach Norwich and Yarmouth, but ran out of money and stopped short.

In frustration local people obtained Parliamentary authority for the Yarmouth and Norwich Railway in 1842. Running via Reedham it opened to the public on 1 May 1844. In 1845 the Railway Mania was under way, and a myriad of railway schemes was put before Parliament. Many of these foundered there, or were authorised but failed to generate investors' commitment.

By 1850 the Eastern Counties Railway had recovered from its financial difficulties of 1836 and had connected practically every town of importance in East Anglia into its system. For some years the Eastern Counties Railway had successfully resisted the promotion of independent railways in its area but this could not continue indefinitely, and some local lines began to obtain authorisation.

The East Anglian Railways company was an amalgamation of three earlier companies, the Lynn and Dereham Railway, the Lynn and Ely Railway and the Ely and Huntingdon Railway. The company became bankrupt early in 1851 and the Great Northern Railway, operating the East Coast Main Line at Peterborough, leased the line. Using running powers between its line at Peterborough and March over the Eastern Counties Railway, it intended to connect to Lynn via the Wisbech line of the East Anglian Railway. However the powers acquired from Parliament did not include a short section between the two companies' stations at Wisbech, and the scheme foundered. The GNR sold the line on to the Eastern Counties Railway in 1852.[4][5][6]

The financial performance of the Eastern Counties Railway declined over the years and in 1862 it was absorbed into the new Great Eastern Railway Company.

Constituents of the M&GNJR

The ultimate formation of the M&GNJR resulted from the fusion of numerous local schemes, though they did not at first aspire to form a connected railway.

Norwich and Spalding Railway

On 4 August 1853 the Norwich and Spalding Railway obtained its Act for a line from Spalding to Sutton Bridge, and from there to Wisbech. Notwithstanding the company's title, reaching Norwich was an (unfulfilled) aspiration for later rather than an immediate intention. The Act stipulated that the other parts of the proposed Norwich and Spalding system could not be opened unless genuine progress was being made with the Wisbech connection.[2][3]

In fact at this time the money market was particularly difficult, partly because of the Crimean War, and the company was unable to attract enough investment. It only managed to build from Spalding to Holbeach, 7 1⁄2 miles, opening to Holbeach for goods on 9 August 1858 and for passengers on 15 November 1858. The Wisbech stipulation appears to have been overlooked for the time being.

The line connected with the Great Northern Railway at Spalding and the GNR agreed to work the line for three years. There were four trains daily except Sundays, with one extra on Tuesdays.[2][4]

The company obtained a further authorising Act to extend from Holbeach to Sutton Bridge, as the earlier powers had expired. Wisbech was omitted this time, but the Act stipulated that no dividend might be declared unless the company proceeded with the promotion of the Wisbech line in Parliament. This was attempted in 1860 but rejected in Parliament, and again in 1862 and 1863. The GNR agreed to extend the working arrangement to ten years from 1 November 1861 for 50% of receipts and to carry out some permanent way improvements on the original section. The Sutton Bridge station was on the site of the later goods station, west of the River Nene. The extension to Holbeach was completed and opened on 1 July 1862.[2][4][3]

Peterborough, Wisbeach and Sutton Bridge

The line connecting Wisbech[note 1] to Sutton Bridge was considered important because Sutton Bridge was an important inland port. Wisbech would have been reached by a southward branch of the Norwich and Spalding Railway, but now an alternative means of making the connection was brought forward. On 28 July 1863 the authorising Act for the Peterborough, Wisbeach and Sutton Bridge Railway was passed. Capital was to be £180,000. The Eastern Counties Railway had just been transformed into the Great Eastern Railway, and powers were to be sought by the PW&SBR to connect to the GER line at Wisbech. The Norwich and Spalding Railway was given running powers between Sutton Bridge and Wisbech. It was the Midland Railway, not the GNR, that secured the contract for operating the new railway for 50% of receipts.[8][4][3]

Lynn and Sutton Bridge Railway

The next section of the future M&GNJR to be built was the Lynn and Sutton Bridge Railway, which was authorised on 6 August 1861 with capital of £100,000.[2][3] It was to connect with the Eastern Counties Railway (soon to be GER) at South Lynn. The authorisation obliged the company to construct a new rail and road bridge at Sutton Bridge, but this was modified by an Act in 1863 which permitted the railway to purchase the existing 1850 road swing bridge and adapt it for railway use as well.[4] The line was opened for goods traffic throughout in November 1864 from a junction some distance south of King's Lynn station. Passenger trains provided by the GNR began on 1 March 1866.[2][1]

Spalding and Bourn Railway

On 29 July 1862 the Spalding and Bourn Railway[note 2] was authorised, also with capital of £100,000. This line was to make an end-on junction at Bourne with an offshoot of the Great Northern Railway, the Bourne and Essendine Railway. The line was opened on 1 August 1866. It ran through practically unpopulated terrain. The GNR worked the line.[2][3]

Rivalry between the GNR and the GER

The Great Eastern Railway was formed on 7 August 1862, from the Eastern Counties Railway and other concerns. The GER made it clear, not least by bitter Parliamentary struggles, to get authorisation for its own line or for running powers to get to Doncaster. Considerable quantities of coal were being brought south from the South Yorkshire Coalfield by the GNR, and the GER sought to take a share of the traffic. Fearing that this might happen, suddenly giving the GER a monopoly of the coal traffic to East Anglia, the GNR started to sponsor friendly railways in the area itself.[2]

PB&SBR extending to Wisbech

The Peterborough, Wisbech and Sutton Bridge Railway now in 1864 got authorisation to make a connecting line at Wisbech to the GER line, and to the harbour. The connection to the GER was in fact not made. On 1 August 1866 its main line opened for traffic. At Peterborough it started from the Midland Railway lines, on the west side of the GNR main line, and crossed both the Midland and GNR track by a bridge. The line was 27 miles in length, to a junction at Sutton Bridge. The Midland Railway worked the trains, working to and from the GER station at Peterborough and calling at the GNR station en route. (Those stations were later called Peterborough East and Peterborough North respectively.)[2]

Midland and Eastern Railway

The Lynn and Sutton Bridge Railway and the Spalding and Bourne Railway amalgamated to form the Midland and Eastern Railway in 1866; the intention was to push westward to Saxby and join the Midland Railway there. This plan was opposed by the Great Northern Railway and the compromise was that the scheme was dropped, but that the Midland Railway was given running powers from over two GNR-sponsored lines: from Bourne to Essendine, and (by reversing there) from Essendine to Stamford; this was not a direct or fast route. The arrangement was agreed, and ratified by the Midland and Eastern Railway Act of 23 July 1866.[3] The Midland and Eastern Railway was operated by the GNR and the Midland Railway jointly, authorised by Act of 1867.[2][4]

The Midland and Eastern Railway leased the Norwich and Spalding line, but the N&SR remained nominally independent (until 1 July 1877).[3] It needed to go to Parliament to plead that it had, in good faith, tried to make the Sutton to Wisbech line, but had been prevented; and that the line had in fact been built by the PB&SBR; this was accepted and the M&SR was released from the prohibition on declaring a dividend. The Midland and Eastern Railway now effectively controlled the whole of the western section of the future M&GNJR, except for the Peterborough to Sutton Bridge line, which was still controlled by the Midland Railway.[2]

The Midland and Eastern was jointly owned by the GNR and the Midland Railway, but it operated more or less independently. The Joint Committee did not meet between 1867 and 1880; trains of the two owning companies ran their own trains on the lines. In this period the network was referred to as the Bourne and Lynn Joint Railway.[2]

GN and GE Joint Line

For several years the Great Eastern Railway had been trying to get access to northern districts, and had been frustrated by the Great Northern Railway's opposition. Nevertheless, the GER repeatedly presented bills for such lines, and the GNR calculated that it was only a matter of time until it was successful. This policy came to fruition in April 1878 during parliamentary hearings on a GER Bill, and negotiations were set in place to establish what became the GN and GE Joint Line, forming a through route from Doncaster to March.

The GNR and the Midland Railway had hitherto dominated the southward flow of Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire coal, and saw that the dominance was vulnerable. This led the GNR and the MR to look favourably at further development of the Bourne and Lynn Joint Railway (Midland and Eastern Railway).[2]

Sutton Dock failure

In 1875 Parliamentary sanction was obtained by an independent shipping company to develop Sutton Dock. Wisbech had traditionally been used as an inland port, but a Sutton Dock, connected to the railway network, could be advantageous, saving part of the difficult navigation up the River Nene. The GNR subscribed £20,000, calculating that this could be an export point for coal. The dock opened on 14 May 1881, and a short branch railway had been constructed to serve it. The day after the opening it was observed that the lock gates were not watertight, and in fact a general failure of the wall of the dock took place. Ships that had entered the dock were got away, but repairs to the dock were said to be impracticable, and the dock was not used again; the GNR had by then expended £55,000 on an unusable dock system.[2]

Great Yarmouth and Stalham Light Railway

Further east it was not until 1876 that the first railway section of the future M&GNJR was approved: the Great Yarmouth and Stalham Light Railway[note 3] was authorised on 27 June 1876;[note 4] capital was £98,000. The line would run north-west for 16 miles; the Yarmouth terminal, later to be known as Yarmouth Beach, was well situated for holidaymakers, but at this stage there was no connection to other railways. The first section, to Ormesby, was opened on 7 August 1877.

From Ormesby to Hemsby opened on 16 May 1878, but there was a legal argument about a level crossing at Hemsby, and the next section to Martham opened from a temporary station north of the level crossing, on 15 July 1878. A temporary station south of the crossing was used from October. The legal position was resolved in Parliament in July 1879 and the permanent Hemsby station opened, and the two temporary stations closed.[2]

Meanwhile, on 27 May 1878 the company got powers to extend to North Walsham, and to change its name to the Yarmouth and North Norfolk Light Railway, with additional capital of £60,000.[2] Its status as a light railway was designed to prevent the Great Eastern Railway from acquiring running powers over the line.[4] Successive openings took place: to Catfield on 17 January 1880 and on to Stalham on 3 July 1880.[2][3]

Lynn and Fakenham Railway

On 13 July 1876 the Lynn and Fakenham Railway was authorised by Parliament, in the face of bitter opposition by GER interests. With capital of £150,000 it was to run from GER-influenced connections near King's Lynn to near Fakenham. Surprisingly the GER made no attempt to take control of this line, in fact making obstructions to the construction process. It was opened to Massingham on 16 August 1879, extending to Fakenham on 16 August 1880.[2][3][1]

On 12 August 1880 the Lynn and Fakenham got approval to extend to Norwich, creating a much sought-after independent line to the city. The line was to pass through Melton Constable, and from that place there was to be a branch to Blakeney Harbour. On 11 August 1881 the Lynn and Fakenham and the Yarmouth and North Norfolk companies together managed at last to get powers to build from Melton Constable to North Walsham, which would connect their systems. In the same Act the Lynn and Fakenham got powers to build from Kelling to Cromer (not actually built), and the Yarmouth and North Norfolk was converted from a light railway to a full system, avoiding the speed and weight restrictions imposed by light railway status. The L&FR opened from Fakenham to Guestwick on 19 January 1882, and from there to Lenwade on 1 July 1882. The final section to Norwich was opened on 2 December 1882. The Norwich station was named Norwich City from the outset. Melton to North Walsham was opened on 5 April 1883.[4][2]

Yarmouth Union Railway

This short line (1 mile 2 chains) was authorised on 26 August 1880, to extend from the Yarmouth and North Norfolk station at Yarmouth to the quay, where it became effectively a tramway, joining the GE tramway there (but not facilitating any through running between the two systems.) The capital was £20,000. The YUR itself was slow to start work, but with the assistance of the Yarmouth and North Norfolk the work was pushed forward and completed on 15 May 1882.[2][3]

Amalgamation: the Eastern and Midlands Railway

Now the many railway companies that were independent of the Great Eastern Railway saw that amalgamation with one another was desirable. On 18 August 1882 the Eastern and Midlands Railway Act was passed, which arranged that on the first day of 1883 the Eastern and Midlands Railway[note 5] was created by amalgamating the Lynn and Fakenham Railway, the Yarmouth and North Norfolk, and the Yarmouth Union Railway. Shares generally were transferred to E&MR stock, but some preference shareholders retained their rights. By the same Act a second stage arranged that the E&MR took over the Midland and Eastern Railway on 1 July 1883. The MR and GNR working arrangements were to continue on those affected routes, and the E&MR could only run trains on those section with the consent of those larger railways.[3][13][14]

The whole line from Bourne to Yarmouth was now under the control of the Eastern and Midlands Railway. The train service at this stage was "lavish,"[2] with six trains daily on the Lynn to Melton section and seven on Melton to Norwich, with numerous short workings. On Sundays it was made possible to spend the day in Yarmouth, by running several trains throughout or connecting in to those trains.[4][2]

Further openings

The section from Melton to Holt was opened on 1 October 1884.

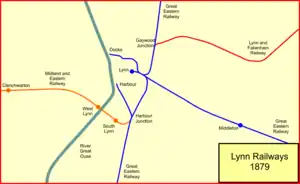

King's Lynn was an important regional centre and port, and the E&MR access to it was inconvenient, involving (from the east) reversal at King's Lynn GER station for through trains, and reliance on that company's grudging acquiescence. Thoughts had long harboured the intention of creating an independent through route and on 2 November 1885 the Lynn Loop was opened for goods traffic; passenger service followed on 1 January 1886. The line ran south of Lynn, connecting from South Lynn goods station to Bawsey. The former connection from Gaywood Road Junction, north of King's Lynn, to Bawsey was closed. The railways had referred to King's Lynn simply as "Lynn" but from this time "Lynn Town" was used instead.

After a suspension of work, the Holt to Cromer section of line was completed by direct labour, and opened on 16 June 1887. A through Kings Cross to Cromer express started running in August 1887, and although the construction had been expensive, the boost to revenue from the new line was considerable. A second train was put on the following year, in the down direction consisting of coaches slipped at Peterborough from a GNR Manchester train. The time from Kings Cross to Cromer was typically 4 1⁄2 hours, but the GER did Liverpool Street to Cromer in 3 1⁄2 hours.

At this time the decision was taken not to go ahead with the Blakeney Harbour branch from Kelling.[2]

On 20 June 1888 a new branch line from North Walsham to Mundesley, a small seaside resort was authorised by Parliament.[3]

Relationships with the Midland and the GNR

For some years there had been continuing friction between the E&MR (and its predecessors) and the Midland Railway over the routing for goods traffic. The E&MR contended that the Midland was obliged to route it to Norwich over the E&MR and not the GER, notwithstanding inferior transit times. The Midland repeatedly protested at Tribunals that no such obligation existed. Now at last a sudden rapprochement took place. A Bill was to be submitted to the 1888 session of Parliament to build a connecting line from the Midland Railway near Ashwell (in the vicinity of Oakham) and Bourne. The E&MR was to build this with Midland financial help, and the following year the Midland would take over the entire western section. Traffic from the eastern section would be directed via the Midland.

At a stroke this would have cut the GNR out of much of the traffic, even though it had constantly been friendly and supportive of the E&MR when the Midland had treated it shabbily. This was "extraordinary conduct" by the E&MR. Mr R A Read was a director, friendly to the Midland but prone to "rash and elaborate schemes", and Wrottesley attributes these schemes to him.[2]

Nevertheless, the new line was sanctioned on 28 June 1888, although a junction to the GNR at Little Bytham was inserted to mollify the GNR.[3]

In the months following the passage of the Act, wiser counsels prevailed, and the E&MR, Midland and GNR boards negotiated a more congenial arrangement. The Midland and GNR would become joint owners of the western section; the eastern section would be unaffected for the time being. The route of the Bourne connecting line to the Midland would be varied, to meet the Midland at Saxby; the connection to the GNR main line at Little Bytham would be retained; and the connecting line west of that point would be Midland property, not E&MR. Ordinary shareholders in the E&MR would get £47 for every £100 worth.[note 6] A joint committee met at Kings Cross on 5 March 1889; it was a Midland and Great Northern Joint Committee, but at this stage no such designation was applied to the railway itself.

Eastern and Midlands Railway in chancery

At the moment when the future seemed satisfactory, the E&MR was plunged into crisis. For some years it had been paying only modest dividends, and profitability had not always been adequate to support outgoings. A Mr W. Jones had been hiring carriages to the company and for some time had not been paid. On 27 June 1889 he obtained judgment in his favour, but the company had no money to comply. At the time there was a system established since 1867 intended to keep a railway in operation for the convenience of the public in this situation: in effect to trade out of bankruptcy.

The "rash" Mr R. A. Read was appointed receiver, and at a shareholders' meeting in November 1889 it was stated that the company had liabilities of over £108,000 on working costs as well as £71,645 on unpaid debenture interest and guaranteed share dividends. At a further meeting on 2 May 1890 the debenture holders accused Read of being to blame for getting the line into this situation, and demanded his removal, as well as a declaration that their debenture payments should rank equally with the railway operating costs, contrary to normal practice when a line was in receivership. Appeals were eventually dismissed and despite the legal and financial difficulties the railway kept running. It was not until 16 August 1892 that a scheme of financial arrangement was finalised.

Improvements despite the crisis

While this was continuing, some capital improvements took place, largely funded by the Midland Railway, Signalling was modernised, some additional crossing places were established as well as some short lengths of double track, and the Bourne to Saxby line continued to be built. On 25 July 1890 an avoiding line at Spalding was authorised, enabling through running past the south of the town. It opened for goods traffic on 5 June 1893, and on the same day the Saxby to Bourne section opened, also for goods only. On 28 June 1892 the Sutton Bridge was authorised to be renewed. It opened on 18 July 1897; it was a swing bridge, and carried road and rail traffic. There were tolls on the road part of the bridge, but these were given up in 1902.

The words Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway appeared in public timetables for the first time in 1890.

The M&GNJR is formed

The 1889 arrangement whereby the Midland and GNR jointly took over E&MR lines applied only to the western section. Now in 1891 the two larger companies indicated that they wished to acquire the eastern section too. This was agreed in October 1892, and a Bill was submitted to the 1893 session of Parliament. The consideration was £1.2 million of Midland and GNR 3% rent stock, although there were complicated provisions for preference and debenture shareholders. Both eastern and western sections transferred to the M&GNJR.

With only minor interference from the GER, the new arrangement passed in Parliament on 9 June 1893: the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway would become an incorporated entity (rather than just a committee delegated by the two principals). 113 miles of railway were involved,[2][3][16][17] so that the M&GNJR network was the longest joint railway in the United Kingdom, by mileage.[1]

Saxby and the Spalding avoiding line opened to passengers

On 1 May 1894 the Bourne to Saxby line was opened to passengers, with additional platforms at Saxby. The formation was made for a southward connecting curve there, but track was never laid on it. The boundary with the Joint Line was at Little Bytham as planned, and the formation of the connection to the GNR was also made, and here too track was never laid on it. the Spalding avoiding line was opened to passenger traffic on the same day, 1 May 1894.

Mundesley to Cromer

An Act of 7 August 1896 authorised the M&GJR to build on from Mundesley (not yet open) to Cromer, passing south of the town and curving back to approach it from the west.

The Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway

Both the GER and the M&GNJR wanted to build a direct coastal line between Yarmouth and Lowestoft; the coastal area and Lowestoft itself were developing and offered the M&GNJR much potential. At the same time the GER wished to develop its access to Mundesley. Notwithstanding the friction between the two companies, a sensible accommodation was finalised on 18 March 1897 by which the GER Bill for the Yarmouth to Lowestoft line and a Mundesley to Happisburgh line would not be opposed by the M&GNJR. The M&GNJR would simply build a connecting curve from its line swinging round the north and west of Yarmouth and connecting in to the new GER line, and have running powers to Lowestoft. A Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway company would be created, and would control the Yarmouth to Lowestoft line (from Gorleston), the North Walsham to Mundesley line, Mundesley to Cromer, and Mundesley to Happisburgh.

The M&GNJR Bill for the curve at Yarmouth passed in Parliament on 6 August 1897, and the establishment of the Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway was enacted on 25 July 1898.

The Lowestoft line opened on 13 July 1903.

Opening to Mundesley

The Mundesley branch opened for goods traffic on 20 June 1898, and to passengers on 1 July 1898. As a joint line (from Antingham Road Junction) it had passenger trains of both companies: nine GER and seven M&GNJR daily. Goods services alternated month by month.

From 1900

In the first years of the twentieth century the M&GNJR was doing well financially. Long distance expresses were run to the area from northern English cities as well as from London. Restaurant cars were put on, as well as workers trains for example bringing fish processing women from northern Scotland for seasonal work. Fish had become an important traffic since the N&SJR connection to Lowestoft had been established.

Although some short sections of double track had been introduced, the majority of the network was single line, and this brought challenges to timekeeping at busy times. The Midland and GNR were operating trains on the line as of right, and the GER had acquired running powers over several sections and to some terminal stations. Conversely the M&GNJR needed the co-operation of the GER for some penetrating workings, at a time when competition with the GER was still intense.

In May 1906 the Committee approved introduction of the Whitaker tablet exchange apparatus. On single line sections, head-on collision due to signalman error was prevented by a tablet system: drivers of trains entering a single line section must be in possession of a physical token, a "tablet" specific to that section, and one only could only be released from control equipment in the one or other of the two signalboxes controlling entry to the section. When the train had passed through the section the tablet was placed in the apparatus at that end of the section, and only now another might be released either there or at the other end of the section. When non-stopping trains passed the tablet had to be passed from the signalman to the fireman of the train, and this could not be done at speed without injury.

Whitaker devised mechanical apparatus to be placed at the lineside and on locomotives to enable the exchange at a higher speed.[18]

During World War I many of the best long-distance express passenger trains were suspended for the duration; the M&GNJR took on considerable additional goods traffic during hostilities, and many of the workforce left for the armed forces. The company maintained an armoured train, constructed by the LNWR at Crewe, continuously in steam from early in 1915 in case of enemy invasion.[19]

After the armistice, government control of the railways continued, and much traffic in demobilised servicemen tested the capacity of the network. There was a general railway strike in the latter months of 1919, and a coal strike in 1921, both of which caused considerable damage to the M&GNJR. The national general strike took place in 1926.[2]

Grouping of the railways

Wartime control of the railways ended on 15 August 1921, and the government passed the Railways Act 1921, which had the effect of transferring most of the railways of Great Britain into one or other of four new large companies, in a process referred to as the "grouping". The Midland Railway was transferred to the new London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) and the GNR and also the GER were transferred to the new London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). The M&GNJR remained unchanged, of course now jointly owned by the LMS and LNER. The rivalry with the GER was naturally at an end. The change took place formally on 1 January 1923.[2]

The long-distance express trains were reinstated progressively, and the LNER particularly emphasised Kings Cross to Cromer traffic.

Holidays at the seaside increased in popularity very considerably after the war, and as well as trains to and from the area, local services for holidaymakers staying in the area were enhanced in the season.

However road competition, both for goods and passengers, began to take a serious toll as roads were improved. at the same time a general depression in the agricultural sector harmed M&GNJR income.[2]

Incorporation into the LNER

The Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway had retained its identity at the grouping of the railways in 1923. In the mid-1930s there was good co-operation between the LMS and the LNER and in 1935 it was agreed that the LNER should manage the operational aspects of the M&GNJR system. This took effect from 1 October 1936.[4] The system consisted of 183 route miles (295 km), of which 40% was double track.[2]

World War II and after

In 1939 World War II started, and once again most long-distance expresses were suspended; staff were called up or volunteered in the services. However the focus of defence, evacuation of children, and later the D-day landings was in the south, not the east. The war ended in 1945. The railways were run down during the war and the government passed the Transport Act 1947, so that the railways became nationalised at the beginning of 1948.

The long distance and holiday trains began to be restored, and holiday camp facilities became popular, and were served by the line.[2]

Local closures

The very low usage of some parts of the M&GNJR system after nationalisation could not be ignored, and some local closures started.

On 6 April 1953 the Cromer to Mundesley section was closed,[4]

On 21 September 1953 the Yarmouth Beach to Gorleston North section closed.[20]

Cromer High was closed on 20 September 1954, services being concentrated on the M&GNJR station, Cromer Beach, which was extended and improved for the purpose.[2]

Eye Green, Thorney and Wryde stations closed to passengers in 1957 and North Drove closed to passengers in 1958.

Diesel trains

Diesel multiple unit vehicles were introduced on the M&GNJR from 18 September 1955, gradually taking over the entire passenger service except the long-distance trains.[2]

Total closure

In May 1958 a report was finalised by British Railways. It concluded that the entirety of the M&GNJR was loss-making, and was largely duplicated by routes of the former GER. Complete closure of passenger services was proposed. Widespread closure of goods services too was contemplated, with only the Spalding to Sutton Bridge, Peterborough to Wisbech, South Lynn to Gayton Road, and Melton Constable to Norwich. The Melton to Cromer branch was to be unaffected by the proposals.

The scale of the closure aroused considerable opposition, mainly focussed on the reduction in amenity to communities, although there was also widespread apathy, reflected in poor turnouts at public meetings.

After deliberation the Transport Users Consultative Committee issued its decision in November 1958, that the majority of the proposed closures should proceed. Retained sections were Spalding to Bourne for goods, Spalding to Sutton Bridge for goods. A new spur would be built at Murrow connecting the M&GN line with the GN&GE Joint line; the Peterborough to Wisbech line would be disconnected at the Peterborough end, and served via the Murrow curve from Whitemoor, at March. Wisbech too would be retained and served from Whitemoor via Murrow.

Further east the Melton Constable to Norwich line would remain open for goods trains, as would the South Lynn to Rudham line. Passenger trains would continue to operate between Melton Constable and Cromer, and between North Walsham and Mundesley. Yarmouth Vauxhall (former GER station) would be extended to handle the additional seasonal passenger traffic.

The closures took place after the last trains on Saturday 28 February 1959. There was much greater public attention to the running of the last passenger trains than there had been to attending the public meetings, but the closure was decisive.[2][4]

Notwithstanding the dire warnings of protesters, a substitute bus service operating from Melton Mowbray to Spalding following closely the route of the railway was almost completely lacking in patronage, and was soon given up.[4]

More closures

The Melton Constable to Sheringham line had retained its passenger services for the time being; however that too closed to passengers after 4 April 1964. North Walsham to Mundesley closed on 5 October 1964.[2]

The Spalding to Sutton Bridge goods connection closed after Friday 2 April 1965.[4]

Topography

Saxby to Sutton Bridge

- Saxby; Midland Railway station;

- Little Bytham Junction; boundary point between Midland Railway and M&GNJR;

- Bourn; opened 16 May 1860; renamed Bourne 1872 - 1893; closed 2 March 1959; convergence of line from Essendine; divergence of line to Spalding;

- Twenty; opened September 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- Counter Drain; opened September 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- North Drove; opened September 1866; closed 15 September 1958;

- Cuckoo Junction; divergence of avoiding line to Welland Junction;

- Spalding; GNR station; opened 17 October 1848; still open M&GNJR route reverses here; divergence northward of GNR and GN&GE Joint lines;.

- Welland Bank Junction; convergence of avoiding line from Cuckoo Junction;

- Weston; opened 1 December 1858; closed 2 March 1959;

- Moulton; opened 15 November 1858; closed 2 March 1959;

- Whaplode; opened 1 December 1858; closed 2 March 1959;

- Holbeach; opened 15 November 1858; closed 2 March 1959;

- Fleet; opened 1 November 1862; closed 2 March 1959;

- Gedney; opened 1 July 1862; closed 2 March 1959;

- Long Sutton; opened 1 July 1862; closed 2 March 1959;

- Dock Junction; divergence of line to Docks;

- Sutton Bridge Junction; convergence of line from Peterborough;

- Sutton Bridge; first station Norwich and Spalding terminus opened 1 July 1862; Lynn and Sutton station opened 1 March 1866; closed 2 March 1959.

Peterborough – Wisbech – Sutton Bridge

- Peterborough Wisbech Junction; divergence from Midland Railway route;

- Dogsthorpe Brick Works;

- Eye; opened 1 August 1866; renamed Eye Green 1875; closed 2 December 1957;

- Thorney; opened 1 August 1866; closed 2 December 1957;

- Wryde; opened 1 August 1866; closed 2 December 1957;

- Murrow; opened 1 August 1866; renamed Murrow East 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Wisbech St Mary; opened 1 August 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- Wisbech; opened 1 August 1866; renamed Wisbech North 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Ferry; opened 1 August 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- Tydd; opened 1 August 1866; closed 2 March 1959.

- Sutton Bridge Junction; above.

Sutton Bridge to Norwich

- Sutton Bridge;

- Cross Keys; east end of swing bridge;

- Walpole; opened 1 March 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- Terrington; opened 1 March 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- Clenchwarton; opened 1 March 1866; closed 2 March 1959;

- West Lynn: opened ???? closed 1886:

- South Lynn; opened 1 January 1886; closed 2 March 1959;

- South Lynn Junction; divergence of line to King's Lynn;

- Gayton Road; opened 1 July 1887; closed 2 March 1959;

- Grimston Road; opened 16 August 1879; closed 2 March 1959;

- Hillington; opened 16 August 1879; closed 2 March 1959;

- Massingham; opened 16 August 1879; closed 2 March 1959;

- Rudham; opened 16 August 1880; renamed East Rudham 1 March 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Raynham Park; opened 16 August 1880; closed 2 March 1959;

- Fakenham Town; opened 16 August 1880; renamed Fakenham West 27 September 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Thursford; opened 19 January 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Melton Constable; opened 19 January 1882; closed 6 April 1964; convergence of line from Cromer; divergence of line to Yarmouth;

- Hindolvestone; opened 19 January 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Guestwick; opened 19 January 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Whitwell and Reepham; opened 1 July 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Lenwade; opened 1 July 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Attlebridge; opened 2 December 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Costessey and Drayton; opened 2 December 1882; renamed Drayton 1 February 1883; closed 2 March 1959;

- Hellesdon; opened 2 December 1882; closed 15 September 1952;

- Norwich City; opened 2 December 1882; closed 2 March 1959.

Melton Constable to Cromer

- Melton Constable; above;

- Holt; opened 1 October 1884; closed 6 April 1964;

- Weybourne; opened 1 July 1901; closed 6 April 1964;

- Sherringham; opened 16 June 1887; renamed Sheringham 1897; M&GN station closed in 1967 when new resited station opened

- West Runton; opened September 1887; still open;

- Runton West Junction; divergence of line to North Walsham;

- Runton East Junction; convergence of line from North Walsham;

- Cromer Beach; opened 16 June 1887; renamed Cromer 1969; still open.

Melton Constable to Yarmouth

- Melton Constable; above;

- Corpusty and Saxthorpe; opened 5 April 1883; closed 2 March 1959;

- Bluestone; opened 5 April 1883; closed 1 March 1916;

- Aylsham Town; 0pened 5 April 1883; simply Aylsham 1902 – 1910; Aylsham North from 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Felmingham; opened 5 April 1883; closed 2 March 1959;

- North Walsham; opened 13 June 1881; renamed North Walsham Town 27 September 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Honing; opened August 1882; closed 2 March 1959;

- Stalham; opened 3 July 1880; closed 2 March 1959;

- Sutton Staithe Halt; opened 17 July 1933; closed 17 September 1958;

- Catfield; opened 17 January 1880; closed 2 March 1959;

- Potter Heigham; opened 17 January 1880; closed 2 March 1959;

- Potter Heigham Bridge Halt; opened 17 July 1933; closed September 1939; reopened June 1948; closed 17 September 1958;

- Martham; opened 15 July 1878; closed 2 March 1959;

- Hemsby; opened 16 May 1878; closed 2 March 1959; a temporary station to north opened 15 July 1878; temporary station to south opened October 1878; temporary stations closed July 1879;

- Little Ormesby Halt; opened 7 August 1877; closed September 1939; reopened June 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Ormesby; opened 7 August 1877; renamed Great Ormesby 21 January 1884; closed 2 March 1959;

- Scratby Halt; opened 7 August 1877; closed September 1939; reopened June 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- California; summer service only; opened 17 July 1933; closed September 1939; reopened June 1948; closed 28 September 1958;

- Caister Camp Halt; summer service only; opened 17 July 1933; closed September 1939; reopened June 1948; closed 28 September 1958;

- Caister; opened 7 August 1877; renamed Caister on Sea 1 January 1893; closed 2 March 1959;

- Newtown Halt; opened 7 August 1877; closed September 1939; reopened June 1948; closed 2 March 1959;

- Yarmouth; opened 7 August 1877; renamed Yarmouth Beach 1883; closed 2 March 1959.[21][14]

Key people

For over 40 years William Marriott served the M&GN and its predecessors, joining the staff of the original contractors, Wilkinson and Jarvis in 1881, serving as Engineer from 1883, Locomotive Superintendent from 1884 and finally becoming Traffic Manager as well in 1919, before retiring in 1924. He is commemorated in the name of the Marriott's Way footpath, much of which follows the trackbed of the M&GN Norwich line, and in the work of the North Norfolk Railway

Murrow flat crossing

At Murrow the M&GNJR crossed the GN&GE Joint Line on the level, one of few such crossings in the UK, and the only one where two joint lines crossed.[1]

Locomotives

Because of the relatively early closure date, most workings throughout the life of the M&GN were operated by steam power. A small number of diesel multiple unit services were run in the final years, alongside the very occasional incursions of early diesel locomotives.

The M&GN mainly used designs from the MR and GNR, but included in its stock some of the older E&M engines, often much rebuilt. The famous Beyer-Peacock engines survived in this way from the early 1880s to the mid-1930s. The best contemporary designs were acquired by the Joint in the 1893 – 1901 period, but as there were no more modern engines forthcoming, the light 0-6-0s and 4-4-0s provided much of the motive power on the line until 1936. From then on the LNER tried various designs on the line, not necessarily bigger or even more recent than the Joint's own engines, but as the M&GN's engines were scrapped, newer engines such as the K2 2-6-0s and B12 4-6-0s became common. The ex-GER "Claud Hamilton" 4-4-0s provided the locomotive backbone of this later period.

From the 1950s, Ivatt 4MTs became the dominant motive power on the system, which achieved a higher degree of standardisation than any other part of British Railways—more than 50 of these "mucky ducks" were allocated here. But there were other types still in use, and among them the line saw Ivatt 2MTs and occasional Standard 4MT and LNER B1 and B17 types.

British Railways' Eastern Region was an early adopter of diesel motive power and the M&GN lines were used by Brush Type 2 locomotives and several early DMU types including Class 101 and Class 105s. A fleet of the latter was commissioned in the mid-1950s to take over all the long-distance locomotive-hauled passenger services, but the line's closure in 1959 saw them re-allocated (especially to the Great Northern suburban commuter workings out of King's Cross, for which they were particularly unsuitable). One M&GN boiler from a Hudswell Clarke 4-4-0T survives, it is hoped this will be rebuilt as a static exhibit.

Badge and livery

The M&GN device consists of images derived from the coats of arms of the four principal cities and towns it served: (clockwise from top left) Peterborough, Norwich, Great Yarmouth and King's Lynn.

For much of the company's life the locomotives were painted a light golden brown, often referred to by paintshop staff as "autumn leaf" or "golden ochre". From 1922 the goods engines were painted dark brown, followed by the rest of the locomotives in 1929. The LNER painted the survivors black. Most of the carriages were ex-GNR and were varnished teak, but some of the older stock and rebuilds were painted and grained to look like teak. Wagon stock was generally brown oxide, the same colour as the GNR used, until 1917 when general stock under the common user agreement began to be painted grey. The number of M&GN wagons declined during the 1920s, and were eventually bought by the parent companies in 1928, leaving only service stock, which was painted red oxide. Under British Railways' control, carriages were often carmine and cream, then maroon.

Cultural impact and heritage

.jpg.webp)

The M&GN was frequently referred to as the "Muddle and Go Nowhere",[22] a fairly self-evident title for a route that served a mostly rural region, but after closure this phrase was commonly replaced with "Missed and Greatly Needed".[23]

The M&GN's memory is kept alive by two heritage railway operations and railway museums. Whilst only the short section between Cromer Beach and Sheringham remains open to regular services,[24] the section of branch line between Sheringham and Holt is operated as the North Norfolk Railway.[25] The station at Whitwell also operates as a heritage centre, with ambitions to restore a section of the M&GN main line.[26] There is also a group dedicated to the study of the line: the M&GN Circle.[27]

M&GN signal boxes survive at numerous locations,[28] with Cromer Beach 'box[29] being open to the public.[30] The 'box from Honing also survives at the Barton House Railway near Wroxham.[31]

The turntable from Bourne engine shed has also survived. This turntable was built in Ipswich in 1933 and installed at Bourne. When the shed closed along with the line in 1959 it was transferred to Peterborough East railway station. After that shed closed the turntable was rebuilt at Wansford station on the Nene Valley railway[32]

Very little rolling stock from the line has been preserved. The North Norfolk Railway have rescued two passenger coaches and a brake van, while a third passenger coach has recently been preserved by the Whitwell & Reepham Railway. Another M&GN brake van survives, No. 23 which was built in 1899, was rescued from Melton Constable in 2000.[33] Two more M&GN coaches survive, No. 40 and 41 (originally GNR), No. 40 is preserved in Alysham [34] and No. 41 survives at the former Raynham Station platform and building. [35] No locomotives survived, with the last complete locomotive being scrapped at the Longmoor Military Railway in 1953.[36]

The "golden ochre" livery has been carried by two industrial locomotives on the North Norfolk Railway,[37] and was later worn by a bus operated by Norfolk Green[38] on routes formerly served by the company.

Notes

- The spelling was Wisbeach until 1877.[7]

- The contemporary spelling; it was altered (in railway terminology) to Bourne in 1894.[9][10]

- This was before the era of the Light Railways Act, 1896, which obviated the securing of an Act of Parliament in some circumstances.

- Clark gives exhaustive details of enactment dates.[11] Wrottesley gives 26 July 1876.[12]

- Midlands as opposed to Midland appears to be correct. Wrottesley uses Midlands consistently, as does Casserley on page 16, and Burgess in several places, and Carter on page 453. Awdry uses Midlands, page 125. Hopwood uses it However Rhodes uses Midland on page 12. Clark uses both in quick succession, quoting titles of Acts: Midlands on page 21; both spellings on page 22; Midland on page 23.

- Wrottesley does not make it clear whether these are face value or market prices.[15]

Footnotes

- Casserley, H.C. (1968). Britain's Joint Lines. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0024-7.

- Wrottesley 1981.

- Clark, Ronald H. (1967). A Short History of the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway. Norwich: Goose and Son.

- Rhodes, John (1982). The Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway. Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 0-7110-1145-1.

- Gordon, D.I. (1977). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 5: The Eastern Counties. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7431-1.

- Moffat, High (1987). East Anglia's First Railways. Lavenham: Terence Dalton Limited. ISBN 0-86138-038-X.

- Wrottesley 1981, p. 19.

- Wrottesley 1981, pp. 16, 19, 21.

- Rhodes 1982, p. 10.

- Wrottesley 1981, p. 20.

- Clark 1967, p. 13.

- Wrottesley 1981, p. 34.

- Carter, E.F. (1959). An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles. London: Cassell.

- Burgess, Neil (2016). Norfolk's Lost Railways. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84033-7556.

- Wrottesley 1981, p. 65.

- Maxwell, Alexander (September 1936). "The Midland and Great Northern Railway : I: Its Traffic". Railway Magazine.

- Hopwood, H.L. (August 1908). "The Midland and Great Northern Railway". Railway Magazine.

- Sekon, G.A. (October 1905). "How Expresses Exchange Trains Staffs and Tablets". Railway Magazine.

- Pratt, Edwin A. (1921). "Armoured trains for coast defence". British railways and the great war. 2. London: Selwyn & Blount. OCLC 835846426.

- Passengers No More Second Edition page 110

- Quick, M.E. (2002). Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology. The Railway and Canal Historical Society.

- "Walpole Cross Keys village website". Walpolecrosskeys.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Trip Back to the Golden Age of Steam". Spalding Advertiser.

- "Bittern Line homepage". Bitternline.com. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "North Norfolk Railway". Nnrailway.co.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Whitwell and Reepham Railway". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011.

- "M&GN Circle".

- "The signal box M&GN listing". Signalbox.org. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Cromer signalbox museum". Cromerbox.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "North Norfolk Railway – Sheringham station facilities". Nnrailway.co.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Barton House Railway signalling". bartonhouserailway.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011.

- "Nene Valley Railway". Nvr.org.uk. 5 April 1977. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- http://www.ws.rhrp.org.uk/ws/WagonInfo.asp?Ref=8217

- http://www.cs.rhrp.org.uk/se/CarriageInfo.asp?Ref=6007

- http://www.cs.rhrp.org.uk/se/CarriageInfo.asp?Ref=5552

- Rowledge, S. "Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway locomotive list". Staplehurst: Robinjay Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Photo of Harlaxton in M&GN livery". Arpg.org.uk. 6 December 2004. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Norfolk Green fleet list" (PDF). Retrieved 17 November 2012.

References

- Wrottesley, A.J. (1981). The Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8173-3.

Further reading

- Becket, W.S. The District Controller's View No.12: Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway: M&GN Railway Operating in the 1950s. Xpress Publishing. Detailed timetables and descriptions of all line workings, including freight

- Clark, M.J. Railway World Special – The M&GN. Ian Allan.

- Clark, R.H. Scenes from the M&GN. Moorland.

- Clark, R.H. A Short History of the M&GN Joint Railway. Goose & Son.

- Digby, Nigel. A Guide to the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway. Ian Allan.

- Digby, Nigel. The Stations & Structures of the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway Vol.1. Lightmoor Press. Architecture and civil engineering, station plans Lowestoft to Melton Constable

- Digby, Nigel. The Stations & Structures of the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway Vol.2. Lightmoor Press. Signalling and permanent way, station plans Norwich to Peterborough and Spalding

- Digby, Nigel. The Liveries of the Pre-Grouping Railways Vol.2 (East of England & Scotland). Lightmoor Press. Chapter on M&GN liveries

- Digby, Nigel. The Liveries of the M&GN. M&GN Circle.

- Greeno, Dennis. M&GN in Colour – Vols.1 - 4. M&GN Jt Railway Society.

- Squires, Stewart; Hollamby, Ken, eds. (2009). Building a Railway: Bourne to Saxby. Lincoln Record Society. ISBN 978-0-901503-86-2. An extraordinary collection of photographs by resident engineer Charles Stansfield Wilson, taken 1890–93, showing the construction of this extension of the M&GN

- Wells, A.M. The Locomotives of the M&GN. HMRS. A detailed and definitive work

- Whitaker, A.C. Running a Norfolk Railway. M&GN Circle.

- Wilkinson, E. Operation Norfolk: Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway Passenger Services 1954. Xpress Publishing. Detailed timetables and descriptions of passenger workings

- Hill, Roger; Vessey, Carey (1995). British Railways Past and Present – 27 Lincolnshire. Past & Present Publishing. Annotated photographs some of which are of the M&GN

Middleton Press "Encyclopedia of Railways" series, featuring annotated track plans and small photographs:

- Adderson, Richard; Kenworthy, Graham (1998). Branch Lines Around Cromer. Middleton Press.

- Adderson, Richard; Kenworthy, Graham (2008). Branch Lines Around Lowestoft. Middleton Press.

- Back, Michael (2009). Branch Lines Around Spalding – M&GN Saxby to Long Sutton. Middleton Press.

- Ingram, Andrew (1997). Branch Lines Around Wisbech. Middleton Press.

- Adderson, Richard; Kenworthy, Graham (2007). Melton Constable to Yarmouth Beach. Middleton Press.

- Back, Michael (2008). Peterborough to King's Lynn: part of the M&GN. Middleton Press.

- Adderson, Richard; Kenworthy, Graham (2011). South Lynn to Norwich City via Melton Constable. Middleton Press.

External links

![]() Media related to Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway at Wikimedia Commons